Social Justice Report 2006: Chapter 4: International developments on the rights of indigenous peoples – Closing the ‘protection gap’

Social Justice Report 2006

Chapter 4: International developments on the rights of indigenous peoples – Closing the ‘protection gap’

Chapter 2 << Chapter 3 >> Chapter 4

- International developments on the rights of indigenous peoples

- United Nations Reform and human rights

- The making of global commitments to action – The Millennium Development Goals and the Second International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People

- Developments in recognition of the rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Summary of international developments – the current situation

- Closing the ‘protection gap’ – Implementing a human rights based approach to Indigenous policy and service delivery in Australia

- Conclusion and recommendations

In recent years there have been significant developments at the international level that impact upon the recognition and protection of the human rights of indigenous peoples. Most notably, there have been: i) reforms to the machinery of the United Nations (UN) and the emphasis given to human rights within that system; ii) the making of global commitments to action, through the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the Second International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People; and iii) the further elaboration of human rights standards as they apply to indigenous peoples. These developments address the dual needs of ensuring that UN processes are more accessible and better address the needs of indigenous peoples; and recognising that there are additional indigenous-specific protections that are required if the human rights of indigenous peoples are to be fully realised.

Developments in both of these areas in recent years have begun to provide a solid platform for the protection of the human rights of indigenous peoples into the future, through international processes as well as within countries. This is despite there remaining significant challenges – such as the need to finalise the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Much of the focus at the international level has now begun to address the need for implementation. There exists concern at the existence of a ‘protection gap’ between the rhetoric and commitments of governments relating to the human rights of Indigenous peoples and the activities of governments on the ground. This ‘protection gap’ exists due to limited consideration of the government’s human rights obligations in the settling of policy and delivery of programs as they affect indigenous Australians.

Increasingly, developments at the international level have emphasised the need to close this ‘protection gap’ by activating the commitments of governments to human rights. There is a clear need to create a direct relationship between the commitments and obligations taken on by our government at the international level and the policies and programs on Indigenous issues within Australia.

This chapter sets out those key developments that have occurred at the international level, particularly in the past three to five years.[1] It also considers the status of those critical issues that remain under consideration within the UN system and that will have significant implications for the recognition of indigenous rights into the future.

Recent developments emphasise the importance of adopting a partnership approach that secures the effective participation of indigenous peoples. Accordingly, this chapter also considers what actions ought to be taken within Australia, by governments and by our Indigenous communities and organisations, to facilitate improved partnerships with Indigenous peoples and ultimately to address the ‘protection gap’ between international standards and commitments, and domestic processes.

International developments on the rights of indigenous peoples

The human rights of indigenous peoples[2] are firmly on the agenda of the United Nations. We are currently seeing the results of the advocacy of countless indigenous peoples at the United Nations (UN) level for more than 20 years come to fruition.

This is not to say that the acknowledgement sought by indigenous peoples has been met or that it will be fully met. Such acknowledgement hangs in the balance as the General Assembly of the UN continues to deliberate on the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples until late 2007. It also depends on the implementation of the reform process to the UN generally, such as through the consolidation of mechanisms for participation by indigenous peoples into the new UN Human Rights Council.

But despite this, there have been substantial gains in the recognition of indigenous rights and the importance attached to them throughout the UN system. There is also significant potential for improved protection of indigenous rights through the reforms to the UN framework and mechanisms that are currently underway.

Recent developments can be categorised as follows:

- reforms to the machinery of the United Nations (UN) and the emphasis given to human rights within that system;

- the making of global commitments to action, through the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the Second International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People; and

- the further elaboration of human rights standards as they apply to indigenous peoples, particularly as it relates to securing the effective participation of indigenous peoples in decision-making processes as well as recognising the need to protect indigenous peoples’ collective rights.

There remain challenges relating to these developments. Most notably:

- ensuring indigenous perspectives in the human rights system of the United Nations into the future;

- integrating indigenous perspectives into the MDG process;

- implementing the objectives and Program of Action for the Second Decade for the Worlds Indigenous People; and

- achieving final acceptance of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by governments in a manner that maintains the integrity of the Declaration, and then ensuring that the Declaration is implemented both internationally and domestically.

This part of the chapter reviews recent developments and reflects on the current challenges being faced at the international level in the ongoing task of securing recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples. It is intended to provide a tool for indigenous peoples to have a greater awareness of international issues and international processes, which can then be utilised within their communities.

1) United Nations Reform and human rights

Over the past two years the UN system has continued to implement a substantial program of reform.[3] This has largely resulted from the outcomes of the UN World Summit held in New York in September 2005. The reform process sets the broader framework within which to consider the level of protection that is provided for the human rights of indigenous peoples worldwide.

- The ‘In larger freedom’ report and World Summit

In early 2005, the then Secretary General of the UN, Kofi Annan, released a report outlining his vision for the United Nations into the future. Titled In larger freedom: towards development, security and human rights for all, [4] the report took stock of progress towards achieving the outcomes of the UN Millennium Summit of 2000, including the Millennium Development Goals.[5] The report and its proposals for reform formed the basis of deliberations at the World Summit of leaders at UN headquarters in New York in September 2005.

The Secretary-General focused on the structural change required at the UN level to revitalise international cooperation and to ensure that the machinery of the UN was capable of supporting the achievement of the MDGs. The Secretary-General set out the challenge faced by the UN in the introduction to the report:

Five years into the new millennium, we have it in our power to pass on to our children a brighter inheritance than that bequeathed to any previous generation... If we act boldly — and if we act together — we can make people everywhere more secure, more prosperous and better able to enjoy their fundamental human rights.

All the conditions are in place for us to do so... In an era of global abundance, our world has the resources to reduce dramatically the massive divides that persist between rich and poor, if only those resources can be unleashed in the service of all peoples. After a period of difficulty in international affairs, in the face of both new threats and old ones in new guises, there is a yearning in many quarters for a new consensus on which to base collective action. And a desire exists to make the most far-reaching reforms in the history of the United Nations so as to equip and resource it to help advance this twenty-first century agenda.[6]

There were two key aspects to the Secretary-General’s proposals that have influenced the reforms that were subsequently agreed at the World Summit. First, he sought to achieve better integration of the objectives of the UN by recognising the equal importance of efforts to protect human rights, alongside focussing on development and security. This focus required an ‘upgrading’ of the importance of human rights in the overall operations of the UN system. Second, he also sought to address the problem of lack of implementation by governments of their substantial commitments and legal obligations, particularly in relation to human rights as well as the achievement of the MDGs.

The Secretary-General’s proposals were focused across three key objectives for UN activity:

- freedom from want (through making the right to development a reality for everyone, including through achievement of the MDGs);

- freedom from fear (addressing security through improved international consensus and implementation); and

- freedom to live in dignity (by making real the commitments of governments to promote democracy and strengthen the rule of law, as well as respect for all internationally recognized human rights and fundamental freedoms).

The Secretary-General’s report sets forth how the foundation of any reform has to acknowledge the inter-relationship between these issues. It states that ‘Not only are development, security and human rights all imperative; they also reinforce each other’.[7] Accordingly:

we will not enjoy development without security, we will not enjoy security without development, and we will not enjoy either without respect for human rights. Unless all these causes are advanced, none will succeed. In this new millennium, the work of the United Nations must move our world closer to the day when all people have the freedom to choose the kind of lives they would like to live, the access to the resources that would make those choices meaningful and the security to ensure that they can be enjoyed in peace.[8]

The report therefore recommended changes to the UN human rights mechanisms. In particular it called for the establishment of a Human Rights Council, which would replace the existing Commission on Human Rights. The creation of a Council would see human rights elevated to a higher level within the UN structure.[9] As the Secretary-General explained:

The establishment of a Human Rights Council would reflect in concrete terms the increasing importance being placed on human rights in our collective rhetoric. The upgrading of the Commission on Human Rights into a full-fledged Council would raise human rights to the priority accorded to it in the Charter of the United Nations. Such a structure would offer architectural and conceptual clarity, since the United Nations already has Councils that deal with two other main purposes — security and development.[10]

This reform would also be accompanied by other measures – such as a continued focus on harmonising the working methods of the human rights treaty committee system, and by increasing, in a sustainable way, the capacity of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

The Secretary-General made clear that such reform needed to be accompanied by a redoubling of efforts by governments to meet their human rights obligations:

When it comes to laws on the books, no generation has inherited the riches that we have. We are blessed with what amounts to an international bill of human rights, among which are impressive norms to protect the weakest among us, including victims of conflict and persecution... But without implementation, our declarations ring hollow. Without action, our promises are meaningless.[11]

The time has come for Governments to be held to account, both to their citizens and to each other, for respect of the dignity of the individual, to which they too often pay only lip service. We must move from an era of legislation to an era of implementation. Our declared principles and our common interests demand no less.[12]

The Secretary-General referred to this as the ‘implementation challenge’. He further elaborated this challenge in relation to the Millennium Development Goals as follows:

The urgent task in 2005 is to implement in full the commitments already made and to render genuinely operational the framework already in place... The September summit must produce a pact for action, to which all nations subscribe and on which all can be judged. The Millennium Development Goals must no longer be floating targets, referred to now and then to measure progress. They must inform, on a daily basis, national strategies and international assistance alike. Without a bold breakthrough in 2005 that lays the groundwork for a rapid progress in coming years, we will miss the targets. Let us be clear about the costs of missing this opportunity: millions of lives that could have been saved will be lost; many freedoms that could have been secured will be denied; and we shall inhabit a more dangerous and unstable world.[13]

Many of the proposals of the Secretary-General contained in the In larger freedom report were adopted at the World Summit in September 2005, particularly those related to human rights.[14]

The World Summit resolved:

- to strengthen the United Nations human rights machinery with the aim of ensuring effective enjoyment by all of all human rights and civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development; and

- to integrate the promotion and protection of human rights into national policies and to support the further mainstreaming of human rights throughout the United Nations system.[15]

The Summit also supported ‘stronger (UN) system-wide coherence’ including by ‘strengthening linkages between the normative work of the United Nations system and its operational activities’ and ‘ensuring that the main horizontal policy themes, such as sustainable development, human rights and gender, are taken into account in decision-making throughout the United Nations’.[16]

To achieve this, the World Summit agreed to replace the Commission on Human Rights with a new Human Rights Council.[17] The General Assembly subsequently adopted a resolution establishing the Council and establishing its functions in March 2006.[18]

- The creation of the Human Rights Council

The creation of the Human Rights Council, and the settling of its working methods, has been the main focus of activity in the UN human rights system since the World Summit.

The Human Rights Council was created as a subsidiary of the General Assembly of the UN (i.e., it is at a higher level than the Commission on Human Rights was). It retains many of the features of the Commission on Human Rights, including a focus on:

- promoting universal respect for human rights;

- addressing situations of violations of human rights, including gross and systematic violations; and

- promoting the effective coordination and mainstreaming of human rights within the United Nations system.

The resolution establishing the Council emphasises that it shall promote the indivisibility of all human rights: civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development.[19]

The functions of the Human Rights Council are set out in Text Box 1 below.

Text Box 1 – Functions of the United Nations Human Rights Council[20]

(a) Promote human rights education and learning as well as advisory services, technical assistance and capacity-building, to be provided in consultation with and with the consent of Member States concerned;

(b) Serve as a forum for dialogue on thematic issues on all human rights;

(c) Make recommendations to the General Assembly for the further development of international law in the field of human rights;

(d) Promote the full implementation of human rights obligations undertaken by States and follow-up to the goals and commitments related to the promotion and protection of human rights emanating from United Nations conferences and summits;

(e) Undertake a universal periodic review, based on objective and reliable information, of the fulfilment by each State of its human rights obligations and commitments in a manner which ensures universality of coverage and equal treatment with respect to all States; the review shall be a cooperative mechanism, based on an interactive dialogue, with the full involvement of the country concerned and with consideration given to its capacity-building needs; such a mechanism shall complement and not duplicate the work of treaty bodies; the Council shall develop the modalities and necessary time allocation for the universal periodic review mechanism within one year after the holding of its first session;

(f) Contribute, through dialogue and cooperation, towards the prevention of human rights violations and respond promptly to human rights emergencies;

(g) Assume the role and responsibilities of the Commission on Human Rights relating to the work of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, as decided by the General Assembly in its resolution 48/141 of 20 December 1993;

(h) Work in close cooperation in the field of human rights with Governments, regional organizations, national human rights institutions and civil society;

(i) Make recommendations with regard to the promotion and protection of human rights; and

(j) Submit an annual report to the General Assembly.

There are a number of significant differences between the Human Rights Council and its predecessor, the Commission on Human Rights. These include its increased status within the UN (due to being created at a higher level than the Commission had operated at) and the direct relationship that the Council enjoys with the General Assembly.

The other most significant difference between the Human Rights Council and the Commission on Human Rights is the addition of a new function as set out at paragraph (e) above – namely, the universal periodic review process.

The Secretary-General explained the purpose of this new function is to make explicit the role of the Human Rights Council as a ‘chamber of peer review’.[21] While there have for some time existed processes within the UN human rights system for dialogues between States on their human rights records, these processes have been criticised for being overtly political or ineffective (in the case of various procedures of the Commission on Human Rights) or have not been utilised (in the case of State-to-State complaint procedures under various human rights treaties).[22]

The new universal periodic review function is intended to foster the capacity of the Human Rights Council to provide a forum for the regular scrutiny of the human rights records of all Member States of the UN. As the Secretary-General has stated:

(The universal periodic review mechanism’s) main task would be to evaluate the fulfilment by all States of all their human rights obligations. This would give concrete expression to the principle that human rights are universal and indivisible. Equal attention will have to be given to civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, as well as the right to development... Under such a system, every Member State could come up for review on a periodic basis.[23]

This mechanism is intended to ‘complement but... not replace’[24] reporting procedures under human rights treaties. Those reporting procedures arise from ‘legal commitments and involve close scrutiny of law, regulations and practice with regard to specific provisions of those treaties by independent expert panels’.[25] By contrast:

Peer review would be a process whereby States voluntarily enter into discussion regarding human rights issues in their respective countries, and would be based on the obligations and responsibilities to promote and protect those rights arising under the Charter and as given expression in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Implementation of findings should be developed as a cooperative venture, with assistance given to States in developing their capacities.

Crucial to peer review is the notion of universal scrutiny, that is, that the performance of all Member States in regard to all human rights commitments should be subject to assessment by other States. The peer review would help avoid, to the extent possible, the politicization and selectivity that are hallmarks of the Commission’s (on Human Rights) existing system... The findings of the peer reviews of the Human Rights Council would help the international community better provide technical assistance and policy advice.[26]

Under the periodic review process, every State would regularly be reviewed every four years. This would reinforce that domestic human rights concerns are truly matters of legitimate international interest.

The Secretary-General argued that this review process ‘would help keep elected members accountable for their human rights commitments’.[27] Under the resolution establishing the Human Rights Council, members elected to the Council are required to ‘uphold the highest standards in the promotion and protection of human rights’, to ‘fully cooperate with the Council and be reviewed under the universal periodic review mechanism during their term of membership’.[28]

Similarly, when casting votes in elections for the Council, members of the UN are required to ‘take into account the contribution of candidates to the promotion and protection of human rights and their voluntary pledges and commitments made thereto’. They may also by a two-thirds majority of the General Assembly ‘suspend the rights of membership in the Council of a member of the Council that commits gross and systematic violations of human rights’.[29]

The processes for the conduct of the universal periodic review mechanism are to be developed within the first year of the Council’s operation (i.e., by June 2007). The detail of how the Council will perform this function remains to be settled.[30]

Non-government organisations and Indigenous Peoples Organisations have identified the universal periodic review process as a significant process for improving the scrutiny of human rights issues within the Human Rights Council. In particular, it has the potential to provide a powerful tool for highlighting ongoing concerns about Indigenous rights.[31]

It remains to be seen how open the process for participation in the universal periodic review will be made (such as by enabling interventions by non-government organisations (NGOs) in any dialogue process, or the making of submissions for consideration as part of the review). Current discussions in Geneva on this process are considering the involvement of independent experts in preparing analytical and evaluative documents as the basis for the review, identifying key issues for dialogue, drafting the final report with conclusions and recommendations and follow up actions.

Regardless of the formal procedures adopted, however, the review process will provide an opportunity to focus international attention on the human rights records of all States. At its most limited, this could occur through the preparation of parallel reports on key issues of human rights compliance by non-government organisations. At best, it could be facilitated through direct participation of NGOs and of independent UN experts in the review processes within the Council.

As such, this mechanism should provide an opportunity to create a connection between domestic policy debate and international dialogue about the human rights record of a country. This potential is discussed further in Part 2 of this chapter.

The timetable for which countries will be subject to the review process in what year has not been settled as yet. However, it has been agreed that every year both countries that are currently members of the Human Rights Council as well as non-members of the Council will be included in the annual list for review.

The fact that Australia is not currently a member of the Council, and is unlikely to become one until at least 2015, will not prevent the possibility of Australia being reviewed under this process in the next year or two.[32]

- Indigenous participation in the processes of the Human Rights Council

In establishing the Human Rights Council, it was decided that all the existing processes of the Commission on Human Rights would be retained for a minimum period of twelve months.

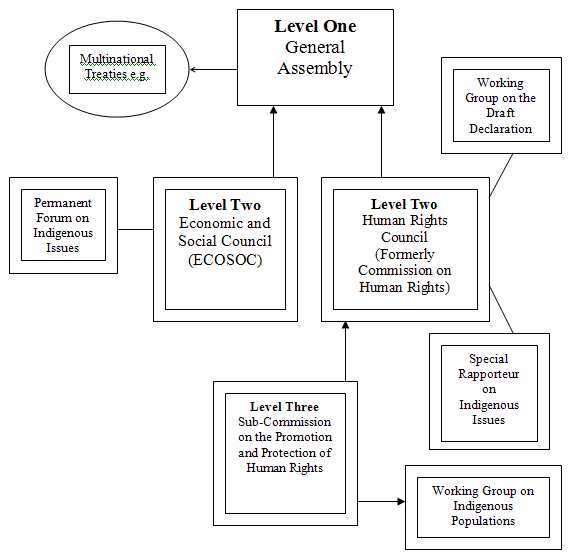

As a result, the UN structure as it currently exists and as it relates specifically to indigenous peoples is shown in Diagram 1 below.

Diagram 1: Overview of Indigenous mechanisms within the UN system, with a focus on human rights procedures

From an Indigenous perspective, this means that the Human Rights Council has retained, but is currently considering the future status of, the following relevant mechanisms:

- The system of Special Rapporteurs who report to the Human Rights Council: These Special Rapporteurs are appointed as experts and provided with a mandate which they exercise independently of the Council. It includes Rapporteurs on specific issues such as health, housing, education and so forth. These Rapporteurs are obliged to consider the distinct problems of discrimination against Indigenous peoples within their mandated areas. It also includes the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous peoples, who prepares a report to the Council each year (usually on a chosen topic or theme), can receive complaints (or communications) from indigenous peoples, and who can also conduct country visits.[33]

- The Sub-Commission on the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights: The Sub-Commission is comprised of a number of independent experts who provide advice to the Council (and formerly the Commission on Human Rights) on key issues. The Sub-Commission’s members have initiated and prepared numerous reports on indigenous human rights issues over the years, such as on indigenous peoples’ relationship to land; treaties between States and indigenous peoples; and indigenous peoples’ permanent sovereignty over natural resources.[34]

- The Working Group on Indigenous Populations (WGIP): The WGIP consists of five members of the Sub-Commission, who report back to the Sub-Commission and through it to the Human Rights Council. Through open meetings (usually lasting for one week annually in Geneva that occurs mid-year) the Working Group has facilitated the participation of indigenous peoples in reviewing the extent to which indigenous peoples enjoy human rights globally, as well as identifying areas for the further development of human rights standards relating to indigenous peoples. Most notably, it has produced the initial version of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, as well as guidelines and draft principles relating to numerous issues, such as indigenous heritage protection, and the principle of free, prior and informed consent.[35]

The Working Group on the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples also continued to exist when the Human Rights Council was created. However, with the adoption by the Human Rights Council of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in June 2006, the mandate of the Working Group was fulfilled and the Working Group ceased to exist.

These procedures and mechanisms within the UN human rights system are also supplemented by the work of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

As shown in Diagram 1, the Permanent Forum is a specialist body of the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Accordingly, it is not subject to the review of human rights mechanisms. It does, however, have a broad mandate which includes consideration of human rights issues (alongside issues relating to economic and social development, culture, the environment, education and health).

The functions of the Permanent Forum differ from those of the human rights mechanisms that relate to indigenous issues noted above. This is because it is focused on providing expert advice and recommendations on indigenous issues to the ECOSOC, as well as to the various programmes, funds and agencies of the United Nations; and on raising awareness and promoting the integration and coordination of activities relating to indigenous issues within the United Nations system. It does not, therefore, primarily focus on reviewing situations of abuses of human rights or on standard setting. The work of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues is discussed further in the next section of this chapter.

In accordance with the resolution establishing the Human Rights Council, a review has commenced to recommend whether and how any of the existing human rights mechanisms should be improved or rationalized.[36] Any modification proposed to the existing practices must, however, ‘maintain a system of special procedures, expert advice and a complaint procedure’.[37]

As a consequence of this review of all the human rights mechanisms and procedures, the Human Rights Council will be determining by mid-2007 the existence of processes which enable specialist input on indigenous human rights issues. They will also be determining the ongoing processes that enable the participation of indigenous peoples in the revised human rights structure.

The indigenous specific procedures of the Human Rights Council (or the Commission on Human Rights as it then was) were most recently reviewed in 2003 and 2004. The specific focus of that review was to identify any duplication in mandates and procedures and the potential for rationalising processes.[38]

The review noted the existence (at the time) of four mechanisms within the United Nations system that deal specifically with indigenous issues (namely, the WGIP, Special Rapporteur, Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues and Working Group on the Draft Declaration). The 2003 report noted the distinct and complementary mandates of these four mechanisms.[39] The 2004 report then found that:

The two Working Groups, the Special Rapporteur and the Permanent Forum each have a unique and specific mandate within the United Nations system. However, it is also evident that in accomplishing its mandate one mechanism could touch upon subject matters that might be the primary concern of another mechanism. This in itself should not be characterized as an overlap of mandates, but rather as an acknowledgement and reinforcement of the interrelated nature of the many issues facing indigenous peoples. Should any rationalization or streamlining of indigenous mechanisms take place, the unique and specific activities undertaken by each mechanism should be taken into account.[40]

The 2004 Report noted the strong support for the role of the Special Rapporteur,[41] as well as for the continuation of the WGIP by most indigenous organisations and some Member States.[42] As noted in the Social Justice Report 2002, Australia was among a handful of Member States who opposed the continued existence of the WGIP, alongside the United States of America.[43] The 2004 Report also noted strong support for the role of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and for it to be ‘the focal point for indigenous issues within the United Nations system’.[44]

The 2004 report also found that:

Although examined under a different mandate, similar themes are being considered by both the (WGIP) and the Permanent Forum. The themes of Working Group meetings of the last four years have been reflected in substance in the reports and recommendations emerging for the Forum during its first three sessions. As human rights is one of the mandated areas of the Permanent Forum, it has become the practice of indigenous delegates attending the Permanent Forum since the first session to set their suggested recommendations in context by providing a review of developments from the various indigenous regions and their homelands. Coordination of the themes of the Working Group, the Special Rapporteur and the Permanent Forum would seem desirable, in order to avoid duplication and to promote effectiveness.[45]

The report concluded that:

The increased attention being given to indigenous issues within organizations of the United Nations system is a welcome development. The United Nations should continue to mainstream indigenous issues and to expand its programmes and activities for the benefit of indigenous peoples in a coordinated manner... it is clear that every effort must be made to ensure coordination among (the various mechanisms), while recognizing the specific tasks that each is mandated to perform.[46]

Importantly, the UN World Summit in September 2005 had highlighted the ongoing importance of addressing indigenous peoples’ human rights and for maintaining processes for the participation of Indigenous peoples. The Summit reaffirmed:

our commitment to continue making progress in the advancement of the human rights of the world’s indigenous peoples at the local, national, regional and international levels, including through consultation and collaboration with them, and to present for adoption a final draft United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples as soon as possible.[47]

The current review by the Human Rights Council of all existing human rights mechanisms and procedures must be seen in the light of the 2004 review of Indigenous mechanisms, and the ongoing commitment to advancing the human rights of Indigenous peoples in the World Summit document.[48]

As part of the process of reviewing the existing mechanisms, the Human Rights Council has requested advice from the Sub-Commission on the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights outlining its vision and recommendations for future expert advice to the Council, as well as indicating the status of ongoing studies and an overall review of activities.

Indigenous organisations have provided input into this process through the submission of information to the Working Group on Indigenous Populations (WGIP) at its 24th session in July 2006. An overview of the concerns of Indigenous organisations relating to the ongoing mechanisms for Indigenous participation and for ongoing scrutiny of indigenous issues by the Human Rights Council is provided in Text Box 2 below.

Text Box 2 – Summary of proposals by Indigenous Peoples for future United Nations mechanisms to protect and promote the human rights of Indigenous Peoples.[49]

- The Human Rights Council should affirm that the human rights of indigenous peoples will continue to be a distinct and ongoing thematic area of its work.

- It should lay to rest any insecurities among indigenous peoples that the United Nations reform process and ongoing reorganization of the United Nations human rights structures could lead to the diminution or disappearance of existing positive functions which are central to the advancement of the rights of indigenous peoples.

- The Human Rights Council should establish an appropriate subsidiary body on Indigenous Peoples, in fulfilment of all areas of its mandate. In doing so, the Human Rights Council should draw on the advice and assistance of human rights experts, including the growing number of experts among indigenous peoples.

- Existing United Nations arrangements for indigenous peoples have differentiated functions with complementary mandates which do not duplicate each other. Any future arrangements should enhance and not diminish the existing functions provided by:

- the Working Group on Indigenous Populations,

- the Special Rapporteur on the human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous peoples and

- the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

- The adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples means that the Human Rights Council could undertake useful work to promote its implementation, e.g. by providing guidelines for the implementation of specific articles or rights within the Declaration.

- The Declaration warrants the continuation and enhancement of appropriate mechanisms within the United Nations human rights system with the necessary focus and expertise on the rights of indigenous peoples.

- The Indigenous Peoples’ Caucus has identified a number of areas in which further standard-setting and/or review of developments on indigenous peoples’ rights is needed, including:

- Guidelines for the implementation of free, prior and informed consent of indigenous peoples to policies, programmes and projects affecting their rights, lands and welfare;

- The human rights of indigenous women and children and youth;

- Indigenous health, housing, education and other economic, social and cultural rights;

- Examining international standards applicable to development programmes and projects affecting indigenous peoples, and their adequacy for protecting and promoting their human rights;

- The human rights impacts on indigenous peoples in relation to the production, export and unregulated use of banned toxics and pesticides;

- The impacts of militarization on the human rights of indigenous peoples;

- The ongoing human rights impacts of colonial laws and policies on indigenous peoples and possible remedies;

- The marginalization of indigenous peoples in the negotiation and implementation of peace accords and agreements between Governments and armed groups, and their impacts on the human rights of indigenous peoples; and

- Administration of justice for indigenous peoples.

- Access to all future mechanisms should be open to all indigenous peoples’ organizations, and fostering their full and effective participation through written and oral interventions. Indigenous peoples’ attendance and full participation at these meetings should continue to be supported by the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Indigenous Populations, and that the mandate of the Voluntary Fund be amended to enable this to happen.

The independent experts of the WGIP have also made a series of recommendations to the Sub-Commission (and for consideration by the Human Rights Council) identifying the specific needs for continued expert advice on indigenous issues.[50]

In common with Indigenous organisations, the WGIP recommend that ‘Indigenous issues’ should be automatically included in the agenda of all the substantive sessions of the Human Rights Council as a separate agenda item. They also recommend that all special procedures of the Human Rights Council and human rights treaty-monitoring bodies should consider indigenous issues in exercising their mandates.[51]

The WGIP acknowledge the role of the Permanent Forum (including providing advice to the UN directly from indigenous experts, although the Permanent Forum is not a human rights body); and the Special Rapporteur (particularly in relation to advice on the implementation in practice of human rights norms relating to indigenous groups). They state that these mechanisms do not, however, provide the necessary coverage for all human rights issues for Indigenous peoples into the future.

In particular, they argue the ongoing need for:

- An expert human rights body focused on indigenous issues: to consider recent developments on issues which may need to be brought to the attention of the Human Rights Council. Such a body would need to address issues on which there is no study to date, and to address these developments in as dynamic a way as possible, including by means of interactive exchanges. The WGIP have also identified a range of specific areas where the advice of an expert body in the human rights of indigenous peoples could be useful. They include contributing to securing the implementation of the goals of the Second International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People, assisting the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in the field of technical assistance in relation to indigenous peoples and possibly contributing to the Universal Periodic Review process of the Human Rights Council.

- Action-oriented in-depth studies of specific issues affecting the rights of indigenous peoples. Such studies would explore what is needed to achieve full legal recognition and implementation in practice of the rights of indigenous peoples, with conclusions and recommendations which are submitted to a superior body for discussion and action. This is not within the mandate and/or the current practice of the Permanent Forum or the Special Rapporteur. The WGIP has identified many issues which still require in depth studies. The WGIP members argue that the Special Rapporteur and the Permanent Forum do not have the time or the adequate mandates or resources to engage in such studies.

- Ongoing standard-setting processes. The adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by the Council should not be the end of standard-setting activities within the United Nations system in the field of indigenous rights. There is a need for the drafting of codes of good practice and guidelines with regard to implementation. Such codes are a bridge between a norm and its implementation in practice. Certain concepts in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples would benefit from guidelines on implementation.[52] Such codes need to be drafted by experts in human rights generally, as well as by experts in indigenous issues, with the close involvement of the representatives of as many indigenous peoples and organizations as possible. Standard-setting and the drafting of such codes or guidelines is not within the mandate of either the Permanent Forum or the Special Rapporteur, and they would not have the time to undertake the task.[53]

To achieve this, the WGIP have recommended that:

- there should be an expert body providing advice on the promotion, implementation and protection of the rights of indigenous peoples;

- this expert body should produce in-depth, action-oriented reports and studies and to engage in the elaboration of norms and other international standards relating to the promotion and protection of the rights of indigenous peoples;

- this expert body should be assisted by the widest possible participation of indigenous peoples and organizations; and

- should report to the Human Rights Council through a wider human rights advisory expert body.[54]

The comments from the Indigenous Peoples Caucus and the recommendations of the WGIP indicate what is at stake with the current review process being undertaken by the Human Rights Council.

The preliminary conclusions of the Working Group established by the Human Rights Council to review the existing mechanisms suggests that the Sub-Commission will be abolished and replaced with a new body, likely to be called the ‘Expert Advisory Body’ or the ‘Human Rights Consultative Committee.’[55] The role and functions of this body are yet to be settled, and it is unclear whether it will include a specific focus on Indigenous issues. It is also unclear whether it will replicate the consultative processes that exist through an Indigenous specific advisory body such as the Working Group on Indigenous Populations.

In all likelihood, the biggest threat will come to the continued existence of the Working Group on Indigenous Populations. The need for such a body – either in its existing format or in a revised structure - is clearly articulated above.

The challenge that has emerged through the current human rights reform process is to maintain the capacity for direct participation of and engagement with Indigenous peoples on human rights issues within the structures of the newly created Human Rights Council.

It would be totally unacceptable if one of the outcomes of the reform process was to limit the capacity of indigenous peoples’ participation. Indeed, such an outcome would be contrary to the commitments made at the World Summit to advance recognition of indigenous peoples’ human rights through participatory processes. It would also contradict commitments made by the General Assembly of the UN in relation to the Second International Decade of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, as well as be inconsistent with the emerging processes for implementing a rights based approach to development (discussed further in the next section).

- Integrating human rights across the activities of the United Nations

Accompanying these reforms to the UN structure have been sustained efforts to mainstream human rights across the UN by integrating them into all policies and programs.

This has occurred through the increased recognition of the right to development and the entrenchment within the UN of a human rights based approach to development and poverty eradication.

This has been accompanied by an increased recognition of the right of Indigenous peoples to effective participation in decision making that affects them. These developments have in turn begun to crystallise in a growing acceptance of the emerging concept of free, prior and informed consent.

Previous Social Justice Reports and Native Title Reports have discussed at length the right to development as well as the adoption by the UN agencies of the Common Understanding of a Rights Based Approach to Development Cooperation.[56] In summary:

- The Declaration on the Right to Development (DRD) was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1986. The right to development is recognised as an inalienable human right by virtue of which every human person and all peoples are entitled to participate in, contribute to, and enjoy economic, social, cultural and political development, through which all human rights and fundamental freedoms can be fully realised.

- Accordingly, development is defined as a process which belongs to people, not to States. Article 2(1) of the Declaration states that ‘The human person is the central subject of development and should be the active participant and beneficiary of the right to development.’

- Article 1 of the Declaration also makes it clear that the goal of development is the realisation of all human rights and fundamental freedoms. Development must be carried out in a way which respects and seeks to realise people's human rights. Thus development is not only a human right in itself, but is also defined by reference to its capacity as a process to realise all other human rights.

- This emphasises the universality and indivisibility of human rights: it focuses on improving all rights, civil and political, as well as economic, social and cultural. The preamble to the Declaration notes that the development process ‘aims at the constant improvement of the well-being of the entire population and of all individuals on the basis of their active, free and meaningful participation in development and in the fair distribution of benefits resulting there from’.

- The right to development therefore encompasses the following issues for Indigenous peoples:

- ensuring development is non-discriminatory in its impact and in its distribution of benefits;

- requires free and meaningful participation by all people in defining its objectives and the methods used to achieve these objectives;

- is directed towards the goal of realizing the economic, social, and cultural rights of people;

- facilitates the enjoyment of indigenous peoples' cultural identity, including through respects the economic, social and political systems through which indigenous decision-making occurs; and

- is self-determined development, so that peoples are entitled to participate in the design and implementation of development policies to ensure that the form of development proposed on their land meets their own objectives and is appropriate to their cultural values.[57]

- The importance of ensuring effective enjoyment of the right to development for all peoples has been an ongoing commitment of the UN for some time. It was affirmed in the Vienna Declaration at the World Conference on Human Rights in 1993 (Article 10 states that the right to development is ‘a universal and inalienable right and an integral part of fundamental human rights’). It is also integral to the Millennium Development Goals process (discussed further below) and its importance was recently re-iterated at the World Summit in 2005.

- The UN agencies have committed to ensuring that all their policies and programming are consistent with the right to development through the adoption in 2003 of the Common Understanding of a Rights Based Approach to Development Cooperation.[58]

- The Common Understanding requires that all programmes should contribute to the realisation of human rights; and be guided by human rights standards at all phases of development and planning. It recognises that people should be recognised as active participants in their own development and not as passive recipients. Accordingly, the Common Understanding emphasises the importance of process (through participation and empowerment) as well focusing on marginalised communities, through the adoption of targets and goals that are aimed at reducing disparities in the enjoyment of rights.

These developments to implement into practice the key elements of the right to development place considerable emphasis on participation of affected peoples and individuals.

As recent Social Justice Reports and Native Title Reports have documented, Australia’s existing human rights treaty obligations also emphasise rights of Indigenous peoples to effective participation in decision-making that affects them, either directly or indirectly.[59]

Both the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Human Rights Committee have interpreted common Article 1 of the international covenants (the right of all peoples to self-determination) as applying to the situation of indigenous peoples.[60] Through a number of individual communications and general recommendations, the Human Rights Committee has also elaborated on the scope of Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (the protection of minority group rights) and its application to the land and resource rights of Indigenous communities, and the positive obligation on States to protect Indigenous cultures.[61] The Committee has indicated that in determining whether the State has violated the rights of indigenous peoples under Article 27, it will consider whether measures are in place to ensure their ‘effective participation’ in decisions that affect them.[62]

Similarly, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) has issued a General Recommendation emphasising that the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) places obligations on States who are parties to the Convention to take all appropriate means to combat and eliminate racism against indigenous peoples. It has called on States to:

- recognise and respect indigenous peoples distinct culture, history, language and way of life as an enrichment of the State's cultural identity and to promote its preservation;

- ensure that members of indigenous peoples are free and equal in dignity and rights and free from any discrimination, in particular that based on indigenous identity;

- provide indigenous peoples with conditions allowing for a sustainable economic and social development compatible with their cultural characteristics;

- ensure that members of indigenous peoples have equal rights in respect of effective participation in public life, and that no decisions directly relating to their rights and interests are taken without their informed consent; and

- ensure that indigenous communities can exercise their rights to practice and revitalise their cultural traditions and customs, to preserve and practice their languages.[63]

The CERD has also, under its early warning/ urgent action procedure and periodic reporting mechanism, highlighted the necessity for the informed consent of indigenous peoples in decision-making that affects their lives as an integral component of the right to equality before the law (under Article 5 of the ICERD).[64]

These developments in international law (through binding treaty obligations) and UN policy and practice demonstrate the increased acknowledgement and reliance on human rights as providing a framework for proactively addressing existing inequalities within society and for recognising and protecting the distinct cultures of Indigenous peoples. And there are increasing expectations that this be done on the basis of full and effective participation of affected indigenous peoples.

These developments have been reflected upon by the various indigenous mechanisms within the UN. Both the Working Group on Indigenous Populations and the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues have given detailed consideration to the development through the UN processes and international law of an emerging principle of free, prior and informed consent.

In particular, the following studies and workshops have been conducted that have advanced the understanding of the principle of free, prior and informed consent:

- The WGIP released a preliminary working paper in 2004 on the principle of free, prior and informed consent of indigenous peoples in relation to development affecting their lands and natural resources, to provide a framework for the drafting of a legal commentary by the Working Group on this concept.[65]

- The Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues conducted the International Workshop on Methodologies regarding Free, Prior and Informed Consent and Indigenous Peoples in January 2005. The workshop was a recommendation of the third session of the Permanent Forum, with the issue having arisen continually throughout the first three sessions of the Forum from 2002-2004.[66]

- The Permanent Forum Secretariat co-convened a workshop with my Office at the International Engaging Communities Conference in Brisbane in 2005, titled Engaging the marginalized: Partnerships between Indigenous Peoples, governments and civil society. The workshop developed Guidelines for engagement with indigenous peoples based on international law and practice, and informed by the principle of free, prior and informed consent.[67]

- The WGIP issued a revised working paper on the principle of free, prior and informed consent of indigenous peoples for its 2006 session. Contributions were invited to identify best practice examples to govern the implementation of the principle of free, prior and informed consent of indigenous peoples in relation to developments affecting their lands and natural resources.[68]

- The WGIP also released at its 2006 session a working paper on draft principles and guidelines on the heritage of indigenous peoples that places considerable emphasis on the need to respect the principle of free, prior and informed consent.[69]

Both the Permanent Forum and the WGIP have emphasised that the principle of free, prior and informed consent is not a newly created right for indigenous peoples. Instead, it brings together, or synthesises, the existing legal obligations of States under existing international law (such as the provisions outlined above relating to self-determination, cultural and minority group rights, non-discrimination and equality before the law).[70] In addition, the principle of free, prior and informed consent:

- Has been identified as an integral component in the implementation of obligations under Article 8(j) of the Convention on Biological Diversity. It’s key elements are reflected in the[71]

- Is explicitly named in relation to indigenous peoples in existing international treaties such as ILO Convention (No.169) Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries (see Articles 6 and 7 for example).[72]

- Is also referred to in several contexts in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, as adopted by the Human Rights Council in June 2006 (see Articles 11, 21 and 31 for example).

As the Secretariat of the Permanent Forum have noted:

The principle of free prior and informed is increasingly emerging as a practical methodology within the UN system for designing programs and projects, which either directly or indirectly affect indigenous peoples. It is also a mechanism for operationalizing the human-rights based approach to development.[73]

The Working Group on Indigenous Populations explains the importance of the application of the principle of free, prior and informed consent to indigenous peoples as follows in Text Box 3.\

Text Box 3 – The principle of free, prior and informed consent and Indigenous peoples[74]

Substantively, the right of free, prior and informed consent is grounded in and is a function of indigenous peoples’ inherent and prior rights to freely determine their political status, freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development and freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources - a complex (series) of inextricably related and interdependent rights encapsulated in the right to self-determination, to their lands, territories and resources, where applicable, from their treaty-based relationships, and their legitimate authority to require that third parties enter into an equal and respectful relationships with them based on the principle of informed consent.

Procedurally, free, prior and informed consent requires processes that allow and support meaningful and authoritative choices by indigenous peoples about their development paths.

In relation to development projects affecting indigenous peoples’ lands and natural resources, the respect for the principle of free, prior and informed consent is important so that:

- Indigenous peoples are not coerced, pressured or intimidated in their choices of development;

- Their consent is sought and freely given prior to the authorization and start of development activities;

- Indigenous peoples have full information about the scope and impacts of the proposed development activities on their lands, resources and well-being; and

- Their choice to give or withhold consent over developments affecting them is respected and upheld.

Human rights, coupled with best practices in human development, provide a comprehensive framework for participatory development approaches which empower the poorest and most marginalized sections of society to have a meaningful voice in development. Indeed, this is integral to a human rights-based understanding of poverty alleviation as evidenced by the definition of poverty adopted by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural rights: “in light of the International Bill of Rights, poverty may be defined as a human condition characterized by sustained or chronic deprivation of the resources, capabilities, choices, security and power necessary for the enjoyment of an adequate standard of living and other civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights (E/C.12/2001/10, para. 8).

Moreover, the realization of human rights requires recognition of conflicts between competing rights and the designing of mechanisms for negotiation and conflict resolution. More specifically, human rights principles require the development of norms and decision-making processes that:

- Are democratic and accountable and enjoy public confidence;

- Are predicated on the willingness of interested parties to negotiate in good faith, and in an open and transparent manner;

- Are committed to addressing imbalances in the political process in order to safeguard the rights and entitlements of vulnerable groups;

- Promote women’s participation and gender equity;

- Are guided by the prior, informed consent of those whose rights are affected by the implementation of specific projects;

- Result in negotiated agreements among the interested parties; and

- Have clear, implementable institutional arrangements for monitoring compliance and redress of grievances.

While the WGIP has focused on the application of the principle of free, prior and informed consent in relation to land and resources, the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues has considered the application of the principle across a broader range of issues. They note it applies:

- In relation to indigenous lands and territories; including sacred sites (may include exploration, such as archaeological explorations, as well as development and use);

- In relation to treaties, agreements and other constructive arrangements between states and indigenous peoples, tribes and nations;

- In relation, but not limited to, extractive industries, conservation, hydro-development, other developments and tourism activities in indigenous areas leading to possible exploration, development and use of indigenous territories and/or resources;

- In relation to access to natural resources including biological resources, genetic resources and/or traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples, leading to possible exploration, development or use thereof;

- In relation to development projects encompassing the full project cycle, including but not limited to assessment, planning, implementation, monitoring, evaluation and closure - whether the projects be addressed to indigenous communities or, while not addressed to them, may affect or impact upon them;

- In relation to UN agencies and other intergovernmental organizations who undertake studies on the impact of projects to be implemented in indigenous peoples territories;

- In relation to policies and legislation dealing with or affecting indigenous peoples; and

- In relation to any policies or programmes that may lead to the removal of their children, or their removal, displacement or relocation from their traditional territories.[75]

The Permanent Forum have identified the common elements of the principle of free, prior and informed consent as those set out in Text Box 4 below.

Text Box 4 - Elements of a Common Understanding of the principle of free, prior and informed consent[76]

What?

Free should imply no coercion, intimidation or manipulation;

Prior should imply consent has been sought sufficiently in advance of any authorization or commencement of activities and respect time requirements of indigenous consultation/ consensus processes;

Informed – should imply that information is provided that covers (at least) the following aspects:

- The nature, size, pace, reversibility and scope of any proposed project or activity;

- The reason/s or purpose of the project and/or activity;

- The duration of the above;

- The locality of areas that will be affected;

- A preliminary assessment of the likely economic, social, cultural and environmental impact, including potential risks and fair and equitable benefit sharing in a context that respects the precautionary principle;

- Personnel likely to be involved in the execution of the proposed project (including indigenous peoples, private sector staff, research institutions, government employees and others); and

- Procedures that the project may entail.

Consent

Consultation and participation are crucial components of a consent process. Consultation should be undertaken in good faith. The parties should establish a dialogue allowing them to find appropriate solutions in an atmosphere of mutual respect in good faith, and full and equitable participation. Consultation requires time and an effective system for communicating among interest holders. Indigenous peoples should be able to participate through their own freely chosen representatives and customary or other institutions. The inclusion of a gender perspective and the participation of indigenous women are essential, as well as participation of children and youth as appropriate. This process may include the option of withholding consent.

Consent to any agreement should be interpreted as indigenous peoples have reasonably understood it.

When?

FPIC should be sought sufficiently in advance of commencement or authorization of activities, taking into account indigenous peoples own decision-making processes, in phases of assessment, planning, implementation, monitoring, evaluation and closure of a project.

Who?

Indigenous peoples should specify which representative institutions are entitled to express consent on behalf of the affected peoples or communities. In FPIC processes, indigenous peoples, UN Agencies and governments should ensure a gender balance and take into account the views of children and youth as relevant.

How?

Information should be accurate and in a form that is accessible and understandable, including in a language that the indigenous peoples will fully understand. The format in which information is distributed should take into account the oral traditions of indigenous peoples and their languages.

Procedures/Mechanisms

- Mechanisms and procedures should be established to verify FPIC as described above, including mechanisms of oversight and redress, such as the creation of national mechanisms.

- As a core principle of FPIC, all sides of a FPIC process must have equal opportunity to debate any proposed agreement/development/project. "Equal opportunity" should be understood to mean equal access to financial, human and material resources in order for communities to fully and meaningfully debate in indigenous language/s as appropriate, or through any other agreed means on any agreement or project that will have or may have an impact, whether positive or negative, on their development as distinct peoples or an impact on their rights to their territories and/or natural resources.

- FPIC could be strengthened by establishing procedures to challenge and to independently review these processes.

- Determination that the elements of FPIC have not been respected may lead to the revocation of consent given.

The principle of free, prior and informed consent has recently received important international endorsement by the United Nations General Assembly. In adopting the program of action for the Second International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People, five key objectives were agreed for the Decade. They include:

Promoting the full and effective participation of indigenous peoples in decisions which directly or indirectly affect them, and to do so in accordance with the principle of free, prior and informed consent.[77]

The Program of Action for the Second International Decade was adopted by consensus. In other words, no governments expressed objections to this objective. All governments have committed to advance this objective internationally and through their domestic policies and programmes over the course of the International Decade.

The principle of free, prior and informed consent has emerged as a primary focus for discussion in advancing the rights of indigenous peoples, particularly in relation to land and resources, heritage protection, intellectual property and biological diversity. The exact content of the principle, however, will continue to be debated and negotiated in international forums in the coming years.[78]

2) The making of global commitments to action – The Millennium Development Goals and the Second International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People

As noted earlier in this chapter, the Secretary-General of the UN laid down the ‘implementation challenge’ for the global community in his In larger freedom report in preparation for the World Summit in 2005. He stated:

When it comes to laws on the books, no generation has inherited the riches that we have... But without implementation, our declarations ring hollow. Without action, our promises are meaningless.[79]

The time has come for Governments to be held to account, both to their citizens and to each other, for respect of the dignity of the individual, to which they too often pay only lip service. We must move from an era of legislation to an era of implementation. Our declared principles and our common interests demand no less.[80]

He also defined the challenge as to ‘implement in full the commitments already made and to render genuinely operational the framework already in place’.[81]

For indigenous peoples, there currently exist two frameworks at the global level which provide a focal point for this implementation challenge:

- the Millennium Development Goals, as agreed at the Millennium Summit in 2000 and due to be achieved by 2015; and

- the Second International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People, as agreed in 2004 and also due to end by 2015.

For indigenous peoples, a focus on implementation through these frameworks is particularly crucial. This is due to considerable concern at the limited achievements of the First International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People from 1995 – 2004. Principle among the concerns about the Decade was that governmental action did not match the rhetoric and commitments made to any significant degree.

Similarly, the resolution affirming the Program of Action for the Second International Decade noted ongoing concerns about ‘the precarious economic and social situation that indigenous people continue to endure in many parts of the world in comparison to the overall population and the persistence of grave violations of their human rights’ and accordingly ‘reaffirmed the urgent need to recognize, promote and protect more effectively their rights and freedoms’.[82]

Concerns have also been expressed at the absence of Indigenous participation in the formulation of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). There has been identified an ongoing need to ensure that the MDGs are culturally relevant and able to assist the situation of indigenous peoples.

These concerns have been at the forefront of discussions during the establishment of the Second International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People in 2004 and the approval of a Program of Action for the Decade in 2005.

International efforts over the past two years have sought to ensure that the MDG process and the Second International Decade are mutually reinforcing and complementary in their focus, in order to maximise the opportunities to advance the situation of Indigenous peoples. The Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, in particular, has led these efforts.

- The Millennium Development Goals and Indigenous peoples

At the United Nations Millennium Summit in September 2000, world leaders agreed to a set of time bound and measurable goals and targets for combating poverty, hunger, disease, illiteracy, environmental degradation and discrimination against women. [83] These are commonly referred to as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). At the Millennium Summit, world leaders committed to the achievement of the goals by 2015.

The purpose of the MDGs is set out in the Millennium Declaration as follows:

We will spare no effort to free our fellow men, women and children from the abject and dehumanizing conditions of extreme poverty, to which more than a billion of them are currently subjected. We are committed to making the right to development a reality for everyone and to freeing the entire human race from want.[84]

There are eight MDGs, supported by 18 targets and 48 indicators. The 8 MDGs and 18 targets are set out in Text Box 5 below.

Text Box 5 – The Millennium Development Goals

Goal 1. Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

Target 1: Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people whose income is less than one dollar a day.

Target 2: Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger.

Goal 2. Achieve universal primary education

Target 3: Ensure that, by 2015, children everywhere, boys and girls alike, will be able to complete a full course of primary schooling.

Goal 3. Promote gender equality and empower women

Target 4: Eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education, preferably by 2005, and in all levels of education no later than 2015.

Goal 4. Reduce child mortality

Target 5: Reduce by two thirds, between 1990 and 2015, the under-five mortality rate.

Goal 5. Improve maternal health

Target 6: Reduce by three quarters, between 1990 and 2015, the maternal mortality ratio.

Goal 6. Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases

Target 7: Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS.

Target 8: Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the incidence of malaria and other major diseases.

Goal 7. Ensure environmental sustainability

Target 9: Integrate the principles of sustainable development into country policies and programmes and reverse the loss of environmental resources.

Target 10: Halve, by 2015, the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and sanitation.

Target 11: By 2020, to have achieved a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers.

Goal 8. Develop a global partnership for development

Target 12: Develop further an open, rule-based, predictable, non-discriminatory trading and financial system. Includes a commitment to good governance, development and poverty reduction - both nationally and internationally.

Target 13: Address the special needs of the least developed countries. Includes: tariff and quota-free access for least developed countries' exports; enhanced programme of debt relief for heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC) and cancellation of official bilateral debt; and more generous ODA for countries committed to poverty reduction.

Target 14: Address the special needs of landlocked developing countries and small island developing States (through the Programme of Action for the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States and the outcome of the twenty-second special session of the General Assembly).

Target 15: Deal comprehensively with the debt problems of developing countries through national and international measures in order to make debt sustainable in the long term

Some of the indicators listed below are monitored separately for the least developed countries (LDCs), Africa, landlocked developing countries (LLDCs) and small island developing States (SIDS).

Target 16: In cooperation with developing countries, develop and implement strategies for decent and productive work for youth.

Target 17: In cooperation with pharmaceutical companies, provide access to affordable essential drugs in developing countries.

Target 18: In cooperation with the private sector, make available the benefits of new technologies, especially information and communications.

The Millennium Declaration agreed on a series of ‘fundamental values to be essential to international relations in the twenty-first century’ which underpinned the commitments made in the Declaration, including the MDGs. These agreed values are:

- Freedom. Men and women have the right to live their lives and raise their children in dignity, free from hunger and from the fear of violence, oppression or injustice. Democratic and participatory governance based on the will of the people best assures these rights.

- Equality. No individual and no nation must be denied the opportunity to benefit from development. The equal rights and opportunities of women and men must be assured.

- Solidarity. Global challenges must be managed in a way that distributes the costs and burdens fairly in accordance with basic principles of equity and social justice. Those who suffer or who benefit least deserve help from those who benefit most.

- Tolerance. Human beings must respect one other, in all their diversity of belief, culture and language. Differences within and between societies should be neither feared nor repressed, but cherished as a precious asset of humanity. A culture of peace and dialogue among all civilizations should be actively promoted.

- Respect for nature. Prudence must be shown in the management of all living species and natural resources, in accordance with the precepts of sustainable development. Only in this way can the immeasurable riches provided to us by nature be preserved and passed on to our descendants. The current unsustainable patterns of production and consumption must be changed in the interest of our future welfare and that of our descendants.

- Shared responsibility. Responsibility for managing worldwide economic and social development, as well as threats to international peace and security, must be shared among the nations of the world and should be exercised multilaterally. As the most universal and most representative organization in the world, the United Nations must play the central role.[85]

The Millennium Declaration also reaffirmed the commitment of all Member States to the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations, and rededicated States to support all efforts to uphold, inter alia, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and respect for the equal rights of all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion.

These guiding principles and commitments are repeated here as they indicate that the purposes of the Millennium Summit, as encapsulated in the MDGs, are intended to apply and to benefit all people. This is in accordance with the understanding that human rights are universal, inalienable and indivisible.

It is important to recall this, as the focus in implementing the MDGs to date has been almost exclusively on the developing world.