Social Justice Report 2006: Chapter 3: Addressing the fundamental flaw of the new arrangements for Indigenous affairs – the absence of principled engagement with Indigenous peoples

Social Justice Report 2006

Chapter 3: Addressing the fundamental flaw of the new

arrangements for Indigenous affairs – the absence of principled engagement

with Indigenous peoples

Chapter 2 << Chapter 3 >> Chapter 4

- Developments in ensuring the ‘maximum participation of Aboriginal persons and Torres Strait Islanders in the formulation and implementation of government policies that affect them’

- Engagement with Indigenous peoples at the local level – Indigenous perspectives on Shared Responsibility Agreements

- Addressing the fundamental flaw of the new arrangements – Ways forward

This is the third successive Social Justice Report to report on the

implementation of the new arrangements for Indigenous affairs at the federal

government level. The past two Social Justice Reports have emphasised the

importance of governments ensuring the effective participation of Indigenous

peoples in decision making that affects our lives. This includes the development

of policy, program delivery and monitoring by governments at the national, as

well as state, regional and local levels.

The Social Justice Report 2005 expressed significant concerns about

the lack of progress in ensuring processes were operating to ensure the

participation of Indigenous peoples in policy, particularly at the regional and

national levels. The report also provided a stern warning about the implications

of failing to address this issue as an urgent priority. It stated that the

‘absence of processes for Indigenous representation at all levels of

decision making contradicts and undermines the purposes of the new

arrangements’.[1] The report

called for principled engagement with Indigenous peoples as a fundamental

tenet of federal policy making.

This chapter does three things.

First, it provides an update on the progress made over the past twelve months

in ensuring the ‘maximum participation of Aboriginal persons and Torres

Strait Islanders in the formulation and implementation of government policies

that affect them’ with a particular emphasis on developments at the

national and regional level. It is clear that the mechanisms for Indigenous

participation in the new arrangements remain inadequate. Indeed this ongoing

failure to ensure Indigenous participation in decision making is the fundamental

flaw in the implementation of the new arrangements.

Second, it looks to developments at the local level through Shared

Responsibility Agreements (SRAs) to see how this program of activities is

unfolding. Substantial effort has been devoted to this program of small scale

interventions. This can be justified if it provides a pathway to improving

existing mechanisms for engaging with Indigenous communities at the local level

and identifying the crucial barriers to sustainable development within

communities. It is reasonable to expect such lessons after two years of solid

engagement.

The chapter examines progress under the SRA program by engaging with those

people affected most by them – namely, the Indigenous communities who have

entered into SRAs. This is achieved through a series of interviews with three

SRA communities and through analysing the results of a national survey of two

thirds of those Indigenous communities or organisations that had entered into an

SRA by the end of 2005.

Third, the chapter looks to ways forward which address the significant

concerns that are set out in the chapter. As the chapter makes clear, Government

commitments exist to ensure the maximum participation of Indigenous peoples in

decision-making and these commitments have been consistently re-affirmed. The

concerns in this chapter reflect a problem of implementation of these

commitments.

The absence of appropriate mechanisms for the participation of Indigenous

peoples in the new arrangements is a significant policy failure. It is

inconsistent with our human rights obligations, existing federal legislation,

and the government’s own policies.

The immediate impact of this policy failure is to render Indigenous voices

silent on new policy developments, in the legislative reform process and in the

setting of basic policy parameters and the delivery of basic services to

Indigenous communities. The chapter emphasises the potential danger of the new

arrangements to the well being of Indigenous peoples, if the concerns raised in

this report are not addressed as an urgent priority.

Developments in ensuring the ‘maximum participation

of Aboriginal persons and Torres Strait Islanders in the formulation and

implementation of government policies that affect them’

The importance of regional Indigenous participatory mechanisms in the

new arrangements

The legislation which forms the foundation for the new arrangements, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Act 2005 (Cth), has as one of its

objectives ‘to ensure maximum participation of Aboriginal persons and

Torres Strait Islanders in the formulation and implementation of government

policies that affect

them’.[2]

The government has continually emphasised the importance of ensuring such

participation as an integral component of its arrangements for Indigenous

Affairs. In June 2005, the then Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and

Indigenous Affairs confirmed that the government remained committed to

establishing representative bodies at the regional level:

We have always stated that, following the dissolution of ATSIC Regional

Councils from July 1 this year, there will be room for genuine Indigenous

representative bodies to emerge in their

place.[3]

This commitment has been constantly re-iterated by the Government since. They

have stated that through regional Indigenous Coordination

Centres, ‘the Australian government is committed to real engagement with

Indigenous people in the areas where they

live’.[4]

The Minister for Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs has also

stated that:

We aim to make it simpler for Indigenous people to deal with government. We

want to show respect by encouraging them to be active participants in solving

their own problems...(T)he one-size-fits-all approach will not work. We need different strategies

for urban, rural and remote areas. Indeed we must recognise that every

individual community is different and that local solutions need to be designed

with local people to suit their local

circumstances.[5]

The Government has emphasised that the new arrangements are intended to

ensure that programs are ‘being implemented more flexibly in response to

local Indigenous needs’ and that ‘Indigenous communities at the

local and regional level... have more say in how (funding) is

spent’.[6]

In their implementation, the new arrangements are

underpinned by five key principles. These include:

2. Regional and local need

ICCs are talking directly with Indigenous communities and groups about their

priorities and needs and their longer term vision for the future. Shared

responsibility Agreements (SRAs) may result from these discussions...The Australian government is also progressing negotiations on Regional

PartnershipAgreements (RPAs) to tailor government interventions across a region. RPAs

can also provide a framework for recognising the range of regional Indigenous

engagement arrangements that develop around Australia.5. Leadership

Strong leadership is required to make the arrangements work, both within

government and from Indigenous people.The regional engagement arrangements that Indigenous people establish will

provide leadership and be accountable to the people and communities they

represent.Where Indigenous leadership capacity and organisational governance need to be

strengthened, the Australian government can provide

support.[7]

What is clear from this is that the Government has acknowledged that

mechanisms for Indigenous participation at the regional level are essential if

the whole of government model it is seeking to implement is to work.

Regional Indigenous participatory mechanisms have an essential role in the

new arrangements as the link in the chain that connects policy making from the

top to service delivery that is relevant and appropriate at the grass roots. It

is essential to identify local need and to facilitate regional planning and

coordination.

In materials explaining the operation of the new service delivery

arrangements, the Government explains the role and importance of regional

engagement arrangements and agreement-making processes to facilitate

partnerships between Indigenous peoples and governments. Regional Partnership

Agreements are seen as a key mechanism to achieve this. The Government’s

approach is described as follows:

Through ICCs, the Australian government has been consulting with

Indigenous communities and state/territory governments about regional solutions to

regional needs.Regional Partnership Agreements (RPAs) are negotiated to coordinate

government services and deliver initiatives across several communities in a

region. They are a means of eliminating overlaps or gaps, and promoting

collaborative effort to meet identified regional needs and priorities. They may

also involve industry and non-government organisations.RPAs also seek to build communities’ capacity to control their own

affairs, negotiate with government, and have a real say in their region’s

future.RPAs may include shared responsibility Agreements (SRAs) with local

communities or groups that support the objectives of the

RPA.[8]

RPAs are a tool to facilitate and recognise regional Indigenous engagement

arrangements. As the Government explains:

Regional Indigenous engagement arrangements are evolving in a number of

regions to help Indigenous people talk to government and participate in program

and service delivery. These engagement arrangements are a mechanism for making

and implementing agreements between government and Indigenous people based on

the principles of partnership, shared responsibility and self-reliance.The Australian government does not want to impose structures but will support

and work with arrangements that are designed locally or regionally and accepted

by Indigenous people as their way to engage with government.The government has supported consultation with Indigenous people about the

types of engagement arrangements they want. Communities need time to think

through these issues, and views differ widely across regions on the most

appropriate models.In Western Australia and New South Wales, the Australian and state

governments are already supporting new engagement arrangements in the Warburton

and Murdi Paaki regions respectively.Bilateral agreements with state and territory governments are also pointing

to a variety of approaches to regional engagement. These approaches include

regional authorities in the Northern Territory and ‘negotiation

tables’ in Queensland.Regional Partnership Agreements are a primary mechanism for government to

provide funding for regional Indigenous engagement arrangements. More regional

Indigenous engagement agreements are likely to be finalised as indigenous groups

negotiate with the Australian and other governments on their funding. [9]

Regionally based Indigenous Coordination Centres (ICCs) provide the interface

with Indigenous communities for the establishment of regional indigenous

engagement arrangements and the finalisation of RPAs. To assist in this process

the Government has created four panels of experts to support ICCs, including for

the specific task of ‘developing regional engagement

arrangements’.[10]

Similarly, a ‘multiuse list of community

facilitators/coordinators’ has also been created to compliment the more

specialised and technical services of the Panels of Experts. Members of the

Multiuse List are intended to create links between communities and governments,

coordinate and develop service delivery, support communities and specific

groups, such as women and youth, in identifying their priorities, in negotiating

agreements with government, and in developing new regional engagement

arrangements.[11]

Progress in supporting Indigenous engagement at the regional

level

Last year’s Social Justice Report provided an extensive overview

of developments towards the establishment of regional Indigenous representative

bodies.

The report noted the considerable progress that had been made in negotiating

regional representative arrangements and structures. It reported that

consultations had been conducted across many regions to identify replacement

representative structures during the year, and that OIPC had provided funds

through the ICCs for Indigenous peoples to convene local and regional meetings

to discuss options for new regional representative

arrangements.[12]

An overview of progress on a state-by-state basis showed that there were

promising developments in determining culturally appropriate regional

representative models, although there were gaps and problems with some of the

models.[13] I emphasised the need to

finalise and operationalise representative organisations where negotiations were

largely complete, and to make greater progress in other areas where models had

not yet been finalised.

Overall, I found the situation to be of some concern:

The consequence of the current status of these models is that there are few

mechanisms for Indigenous participation at the regional

level...[14]Addressing the absence of regional representative structures is an urgent

priority for the 2005-06 financial year. It would be wholly unacceptable for

regional structures to not exist and not be operational in all ICC regions by

the end of this period.[15]

The report recommended that the Australian government, in partnership with

state and territory governments, prioritise, with Indigenous peoples, the

negotiation of regional representative arrangements and that Representative

bodies should be finalised and operational by 30 June 2006 in all Indigenous

Coordination Centre regions.[16]

At that time, the Government had finalised one RPA that recognised the

Ngaanyatjarra Council as the representative body for 12 communities spread

across the Ngaanyatjarra lands in Western Australia.

It had also finalised a Shared Responsibility Agreement which recognised the

Murdi Paaki Regional Assembly as the peak regional Indigenous body in the Murdi

Paaki region of far north-west New South Wales. It is understood that the Murdi

Paaki Regional Assembly is now close to signing a RPA to formalise strategic

planning arrangements proposed through community planning processes undertaken

as part of the SRA.

In brief, it is worth recalling developments relating to the creation of

regional representative structures as they stood 12 months ago:

- The government, through ICCs, supported consultations with Indigenous

communities to identify replacement regional representative structures following

the abolition of ATSIC; - At 30 June 2005, when ATSIC Regional Councils ceased to exist, no

replacement representative structures were in place; - The then Minister announced on 29 June 2005 that representative arrangements

had been ‘finalised’ in 10 of the 35 ICC regions, with consultation

and negotiation ongoing in other

regions;[17] and - All State and territory governments had indicated their support for regional

representation in their jurisdictions (based on different models).

As the Social Justice Report 2005 noted, ‘common to

all the existing proposals (for regional structures) is that the federal

government has not as yet outlined in concrete terms how they will support

them’.[18] In particular,

there was no clarity as to how regional bodies would be funded and the type and

level of administrative support they would be provided. The report noted that

Regional Partnership Agreements provided an appropriate model for developing

regional structures.

Throughout the past twelve months, the government has continued to state that

it is committed to establishing regional representative structures. In

correspondence with my Office in December 2006, the Office of Indigenous Policy

Coordination stated that RPAs are the primary mechanism for formally engaging

with Indigenous peoples and communities at a regional level, and that they:

... are a way of harnessing the potential of communities in a region through

genuine partnerships involving many sectors, backed by a serious commitment of

resources.[19]

As discussed further below, commitments to ensure Indigenous participation

and engagement are also contained in each bilateral agreement between the

Australian government and the states and territories.

The Government also released guidelines indicating the parameters of what

support they would provide for regional structures. These guidelines were for

‘Regional Indigenous Engagement Arrangements’ (RIEA) and were

intended to:

... [P]rogress RIEA proposals that are consistent with the Australian

Government’s principles of partnership, shared responsibility and

self-reliance, and to provide feedback to communities on proposals that are not

consistent with the Australian Government’s

objectives.[20]

A notable feature of these guidelines is that they do not use the phrase

‘representative structures’. This language of representation had

been acceptable during the first year of the new arrangements. Importantly, the

various proposals submitted to the government before 30 June 2005 were for

replacement representative structures.

The RIEA guidelines therefore elaborate the shift by the Government from

supporting ‘representation’ to supporting ‘engagement

arrangements’. The parameters for Australian Government funding set out in

the guidelines are as follows:

- Initial Australian Government funding be capped and limited to one year

after which further support be negotiated through RPAs; - Funds support meeting costs such as travel but not sitting fees or

remuneration; - State and Territory Governments participate through RPAs or bilateral

agreements; - The Government retain the right to engage directly with communities or other

bodies; - The Government be assured of the legitimacy of RIEAs among their

constituents; and - RIEAs not be ‘gatekeepers’ or have decision-making

responsibilities concerning Indigenous program

funding.[21]

A second key feature of the guidelines is that they substantially

reduce the scope of what the federal government would consider supporting and

funding. Regional Indigenous Engagement Arrangements will only get funding

support for a year, after which time any further support must be negotiated

through a Regional Partnership Agreement. Whilst this does not necessarily

preclude organisations with a degree of permanency, it shows that engagement

arrangements are to be contingent on RPAs.

The shift in focus that the guidelines present is problematic in that various

proposals were prepared prior to these guidelines being made public and

available. Indeed, the guidelines were in all likelihood developed as a response

to concerns by the government about the content of the proposals developed prior

to 30 June 2005.

This means that proposals submitted by Indigenous communities would be

assessed against guidelines that the proponents were unaware of and which would

require a much narrower and restricted proposal for support to be forthcoming.

The document outlining the guidelines made clear that the guidelines outlined

would be utilised ‘to progress RIEA proposals’ such as the 18 that

had been received at the time. This suggests that the Government would engage

with the proponents of regional models to consider their proposals in light of

the government guidelines.

Over the past eighteen months and since the adoption of these guidelines, the

Government has finalised two RPAs – in Port Hedland and the East Kimberly

(both signed in November 2006).

Neither of these agreements relate to supporting Regional Indigenous

Engagement Arrangements. Instead, they are the result of negotiations within two

trial sites under a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the Government and

the Minerals Council of Australia.

The MoU with the Minerals Council is about building partnerships between the

government, mining sector and Indigenous communities. The MoU negotiation

process involved local Indigenous leaders through the Indigenous Leaders

Dialogue - a forum through which local Indigenous leaders advise the MCA

about Indigenous aspirations and anticipated outcomes from the MoU.

Case studies of these RPAs are included in the Native Title Report 2006. The Report notes that a concern during the

negotiation of the RPAs was the lack of sufficient Indigenous engagement. In

relation to the East Kimberly RPA, the Native Title Report 2006 states that:

From the outset, parties to the RPA saw it as an initiative of the Australian

Government. There is evidence that the negotiation processes were run according

to the Government’s own agenda and plans were hastily developed in a rush

to meet fixed deadlines leaving other parties feeling pressured to follow for

fear of being left behind... The level of community engagement (on the RPA) is

regarded as greatly inadequate.As a result of the lack of

engagement with Indigenous people, there is a critical lack of understanding

within the community about the RPA, and what it aims to deliver. For

example, there was reported confusion between the RPA and other changes to

regional governance arrangements including changes to the Community Development

Employment Project. This kind of confusion has the potential to skew commitment

and expectations of the RPA, and may lead to dissatisfaction with outcomes. In

addition, as long as communities are uncertain about the nature of the RPA, they

will be unable to take advantage of the opportunities it

creates.[22]

Aside from these RPAs emanating from the MoU with the Minerals Council, no

other RPAs have progressed in the past eighteen months.

In researching this report, my Office sought to contact the proponents of

proposed regional arrangements that had been identified by the Minister for

Indigenous Affairs as ‘finalised’ in June 2005. My purpose was to

identify what had transpired over the past 12-18 months and whether the

proposals as submitted had been considered and what advice had been provided

back to the proponents of these bodies in order to advance them (consistent with

the commitment given by the government when it announced its guidelines for

RIEAs). [23]

Those proposals that had been identified as ‘finalised’ related

to the following ICC regions:

- Many Rivers, Northern NSW;

- Gulf and West Queensland;

- Central Queensland;

- Cairns and District Reference Group;

- East Kimberly District Council;

- Kullari Regional Indigenous Body;

- Yamatji Regional Assembly;

- Nulla Wimla Kutja;

- Ngaanyatjarra Council; and

- Murdi Paaki Regional

Assembly.[24]

In Hansard in federal Parliament in May 2006 the Government stated

that two arrangements had been established and were receiving funding support

from the Australian Government and sixteen other reports from Indigenous groups

had been received by the Australian Government for

consideration.[25]

Information on progress was sought initially from the relevant ICCs and the

Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination. For some of the proposed regional

structures, the ICCs advised that they had no contact information for the

proponents of the models and that there had been no activity to advance

discussions within the region over the past year.

In a regular request for information to the OIPC that I make for each Social Justice Report I also specifically requested a region by region

update on progress in advancing RIEAs and in consideration of proposals that had

been submitted to OIPC through the ICCs. The OIPC provided no response to this

question.[26]

Discussions with Indigenous community members who had been involved in

proposing structures for these regions also revealed that little progress had

occurred in progressing RIEAs. Part of the difficulty in this was the fact that

most of the models had been presented by, or were facilitated by, the relevant

ATSIC Regional Council prior to their abolition. Accordingly, there is now no

institutional structure in place to progress the proposals made.

Various community members noted that the process of negotiating an RIEA had

not progressed due to a lack of communication from the OIPC and ICC, with the

proponents not hearing from the local ICC regarding their

proposal,[27] no financial support

from any level of government to facilitate progressing the proposal, lack of

communication on the proposal between the state or territory government and the

federal government, and/ or a lack of support for the proposal by the state or

territory government.[28]

The Government explains the current absence of consultative mechanisms as

follows:

Mr Yates - There was quite a lot of work done in the follow-up to the

abolition of the ATSIC regional councils, typically in conjunction with state or

territory governments where they were reviewing representative arrangements or

machinery for engagement with government. So there has been quite a lot of work

done over the last couple of years, but they have not all translated into

replacement arrangements. As far as possible we were looking to try and support

arrangements which both levels of government would be backing rather than having

multiple layers. Our focus in terms of the future has been on, at the regional

level, the engagement that we are having there where that translates into

regional partnership agreements. We are quite ready and willing to work with the

other parties and provide resources to support the effectiveness of Indigenous

groups engaging with government to enable those regional partnership agreements

to work well.[29]

There is an important change in approach here, from an emphasis on regional structures, to regional processes and agreements, particularly

RPAs.

Given the advanced state of discussions a year ago in a number of regions, it

is quite remarkable that progress towards recognising regional representative

structures has stalled, if not dissipated.

Even more remarkably, the OIPC has sought to suggest that this lack of

progress is a result in a shift in the thinking and preferences of Indigenous

people themselves!

In Senate Estimates they stated:

... what we [FaCSIA] have found is that some of the early thinking in a

number of regions, which was to re-establish something very similar to an ATSIC

regional council, has dissipated. They [Indigenous peoples] have realised that

that is not workable or meaningful for them and they have moved on. So we are in

a situation where we are having to work more case by case in different regions,

and it is taking a while, but the timetable is very much in the hands of

Indigenous people, as is the shape of any engagement arrangements that that

results in.[30]

This proposition needs to be tested further. It is not consistent with the

findings of discussions conducted by my Office and it is not consistent with the

apparent lack of activity by OIPC and ICC to progress this important issue.

As indicated above, immediately following the demise of the ATSIC Regional

Councils and over the course of the first year of the new arrangements, the

government expressed a clear intention to assist Indigenous peoples to establish

replacement bodies for regional participation. After an initial level of

activity by OIPC to this end, this undertaking was quietly dropped and replaced

with a commitment to RIEAs.

It now seems that the federal government would prefer to avoid anything

resembling the ATSIC Regional Council model. I have serious doubts that this

fully represents the will of Indigenous peoples in the regions, or that they

have ‘moved on’ in their thinking.

Given the unqualified nature of the government’s initial undertakings,

a more thorough explanation of what is being done to replace the ATSIC Regional

Councils with appropriate regional representative organisations is called

for.

While it is desirable not to foist a standard model on different regions, and

this is one of the reasons given for the slowness in getting regional engagement

arrangements in place or

supported,[31] I remain concerned

that the vacuum in Indigenous regional participation is creating problems.

It is difficult for Indigenous communities to deal with the volume of

changes, agencies and requirements under the new arrangements and the increasing

entanglements of red tape.[32] There

is a need to support authentic and credible structures and processes for

Indigenous communities that allow them to engage with governments, be consulted,

and where appropriate, provide informed consent.

In my view the government has adopted a cynical and disingenuous approach in

which the apparatus of the new arrangements play no active role in engaging with

Indigenous peoples on a systemic basis to ensure that mechanisms for Indigenous

participation can become a reality.

The Government has clearly stated that one of the priority areas for their

Expert Panels and ‘Multiuse list of community

facilitators/coordinators’ is to assist in the development of regional

engagement arrangements. This demonstrates that they are fully aware that such

arrangements will only become a reality if intensive support is provided to

Indigenous communities to develop models that are suitable to their local

needs.

It is fanciful to expect that RIEAs will emerge solely through the efforts of

Indigenous communities that are under-resourced and that in most instances do

not have the necessary infrastructure to conduct the wide-ranging consultation

and negotiation required to bring a regional engagement structure into

existence.

It is also convenient for Government to leave this issue solely up to

Indigenous peoples to progress. I would suggest that this is done in full

knowledge that the outcome of this approach will be an absence of regional

engagement arrangements.

There is a clear need for special assistance to ensure that Indigenous

peoples are able to, in the words of the object of the Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander Act 2005, ensure the ‘maximum participation of

Aboriginal persons and Torres Strait Islanders in the formulation and

implementation of government policies that affect them’.

Options for addressing this significant failure of the new arrangements are

discussed in detail in the final section of this chapter.

As noted in chapter 2 of this report, a related concern is that each regional

Indigenous Coordination Centre is now developing its own Regional Action Plan

which identifies the key issues that the ICC will focus on in a twelve month

period.

The plans will cover work completed through a variety of mechanisms including

RPAs and SRAs, strategic intervention arrangements and community in crisis

interventions. The plans are to be endorsed by federal government state manager

groups and will highlight the most significant community and government work

which the ICC is involved as well as link into national

priorities.[33]

It is a concern that ICCs are developing such action plans in the absence of

systematic engagement with Indigenous communities at a regional level and in the

absence of Regional Indigenous Engagement Arrangements in nearly all ICC

regions. Ensuring such engagement with Indigenous communities should be a

fundamental pre-requisite to determining service delivery priorities and in the

identification of need for each ICC region.

As I have travelled around the country I have discussed this situation with

Government staff in ICCs and OIPC state offices. These staff, particularly at

the field operative level, are observing the frustration, disengagement and

bewilderment of Indigenous peoples. Many of these staff have had long term

relationships with indigenous communities and peoples and they are experiencing

the pressures of top down impositions that are not likely to see any real and

sustainable outcomes for indigenous people. They also feel disempowered

themselves, and that the culture within the OIPC is one that does not value

their views and concerns. Many have expressed an unwillingness to raise their

concerns for fear of reprisals.

Government would benefit from conducting a confidential survey of all staff

in ICCs to gauge their views on the current directions in implementing the new

arrangements and to raise suggestions on the way forward to achieve sustainable

outcomes.

Indigenous participation in decision making at the national level

Last year’s Social Justice Report provided a detail overview of

the issues relating to Indigenous engagement at the national

level.[34] These include:

- difficulties in ensuring the involvement of Indigenous peoples in

inter-governmental framework agreements (such as health and housing agreements

with the states and territories); - the removal from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Act 2005 (Cth) of previously existing requirements for departments to consult with

Indigenous peoples in planning and implementing their activities; and - the absence of processes for engagement with Indigenous peoples at the

national level.

In the past twelve months, there have been limited changes at the

national level to the situation as described in the Social Justice Report

2005. The government has continued to utilise the National Indigenous

Council (NIC) as the primary source of advice on Indigenous

policy[35] and has not sought to

engage more broadly with Indigenous communities on matters of policy development

that affect our lives.

The result of this has been a noticeably low level of participation of

Indigenous peoples in inquiry processes (such as parliamentary committees) on

matters of crucial importance to Indigenous peoples and a new

‘unilateralism’ in policy development.

There are two principle concerns that I have regarding developments at the

national level over the past 12- 18 months.

- First, we have seen reforms being introduced extremely quickly with limited

processes for consultation and engagement from Indigenous peoples. Limited

processes for engagement are compounded by the lack of capacity of Indigenous

communities and low levels of awareness of the various reforms proposed. During

the course of some reform processes, the government has stated that they are

under no obligation to consult with Indigenous peoples – this has

contributed to the emergence of a culture within the federal government that

does not place sufficient value upon Indigenous engagement and

participation.

- Second, as the government has continued to bed down the new arrangements

they have continued to distance Indigenous peoples from processes for agreeing

to policy priorities – this includes through setting the key priorities

for inter-governmental cooperation through bilateral agreements with the states

and territories without Indigenous participation, and a changed focus in federal

processes, such as through the strategic interventions approach described in

chapter 2.

Last year’s Social Justice Report expressed concern at

the existence of multiple processes to reform Indigenous policy that were taking

place concurrently and the limited ability for Indigenous people and communities

to engage in these processes. I noted my concern that:

... the cumulative impact of the parallel reforms currently taking place is

overwhelming some communities and individuals.This renders it very difficult for Indigenous peoples to participate

meaningfully in policy development, program design and service delivery. This is

particularly so in the absence of representative structures to coordinate and

focus the input of communities, particularly in relation to legislative reform

and inquiry processes.The intention of the reforms is plainly to improve engagement and service

delivery with Indigenous peoples... The rapid rate of the reforms and the

accompanying impact it is having on communities and individuals needs to be

acknowledged by governments.[36]

This situation has continued over the past year.

For example, communities have had to deal with the following ongoing reform

processes that have been occurring simultaneously at the national level:

- Reforms to governance arrangements for Aboriginal councils and associations,

which had been held over for a further twelve months; - Reforms to the CDEP program, as well as processes for the lifting of Remote

Area Exemptions in some remote communities; and

- Reforms of other employment related services, such as Indigenous Employment

Centres, the Structured Training and Employment Program (STEP), and welfare to

work reforms.

At the same time, consultations have been conducted relating

to:

- Reforms to the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act, including

substantial reforms for land tenure arrangements in townships and proposed

changes to the permit system; - Six inter-connected reform processes for different aspects of the native

title system, followed by draft legislation to implement the findings of some of

these consultation processes (with further amendments expected later on);

and - Reforms to the community housing and infrastructure program.

Legislation has also been introduced to the federal Parliament that

impacts on Indigenous communities relating to:

- Land rights reforms in the Northern Territory (through the Aboriginal

Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1975); - Indigenous heritage protection (through the Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984); - Indigenous governance (through the Aboriginal Councils and Associations

Act 1976); - Banning of consideration of Aboriginal customary law in federal sentencing

matters (through the Crimes Amendment (Bail and Sentencing) Act 2006); - The removal of consent procedures for traditional owners in the nomination

of sites for storage of radioactive waste on Indigenous lands (through the Commonwealth Radioactive Waste Management Legislation Amendment Bill

2006); and - Welfare to work reforms (through the Employment

and Workplace Relations Legislation Amendment (Welfare to Work and Vocational

Rehabilitation Services) Bill 2006)

Parliamentary inquiries have also been conducted into:

- petrol sniffing in remote Aboriginal Communities;

- national parks, conservation reserves and marine protected areas;

- the Indigenous

visual arts and craft sector; - Indigenous stolen wages;

- Native Title Representative Bodies (this inquiry was in addition to the four

separate consultation processes on native title issues conducted by the

Attorney-General’s Department); - Indigenous employment;

- health funding;

- the non-fossil fuel energy industry;

- mental health;

- civics and electoral education, including the non-entitlement of prisoners

(of whom Indigenous peoples make up a significant proportion) to vote; and - an identity card (which is likely to have a significant impact on Indigenous

peoples as high users of government services such as the welfare and health

systems).

These activities are just some of the reforms that have occurred at

the national level. They do not include significant reforms at the state and

territory level – such as to governance arrangements and local councils in

Queensland and the Northern Territory; the operation of the state based land

council system, care and protection and adoption systems in NSW; protections

through a Bill of Rights in the A.C.T, Victoria, Tasmania and Western Australia;

and inquiries into family violence and child sexual abuse in NSW and the NT,

among other things.

The consultation processes and reforms at the federal level have also been

difficult for Indigenous peoples to participate in due to the short timeframes

within which consultation for some of the reforms have taken place. The adequacy

of consultation processes for CDEP and related employment changes, for example,

were discussed in Chapter 2 of this report.

An issue of major concern has been the shortness of time for parliamentary

inquiries into issues of relevance to the situation of Indigenous peoples and

particularly for draft legislation. This has been particularly noticeable in

inquiries before the Australian Senate where public consultation on proposed

legislation has consistently been severely curtailed.

For example:

- The Senate Committee inquiry into changes to federal sentencing laws to ban

consideration of Aboriginal customary law was formed on 14 September 2006 with

submissions required to be submitted by 25 September 2006 – just 11 days

later (with the committee due to report by 16 October 2006). Just 5 submissions

were received from Indigenous organisations. The final report noted that the

Government confirmed that 'there was no direct consultation' on the content of

the Bill with groups who could be

affected.[37]

- The Senate Committee Inquiry into the provisions of the amendments to the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1975 was created on 22

June 2006 for inquiry and report by 1 August 2006. The Committee received 4

submissions from Indigenous organisations. The final report of the inquiry (by

both government and non-government members of the Committee) stated:

‘The Committee considers the time made available for this

inquiry to be totally inadequate. The Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern

Territory) Act is one of the most fundamentally important social justice

reforms enacted in Australia and these are the most extensive and far reaching

amendments that have been proposed to the Act. There was insufficient time for

many groups to prepare submissions and a single hearing was complicated by the

necessity to include a number of teleconferences within the hearing.

Additionally, time constraints prevented the Committee hearing from a number of

witnesses’.[38]

The lack of emphasis given to ensuring that Indigenous peoples are able to

participate in decision making processes that affect us is of serious concern.

As I note elsewhere in this report, the lack of engagement generally with

Indigenous peoples ensures that the system of government, of policy making and

service delivery, is a passive system that deliberately prevents the active

engagement of Indigenous peoples. This contradicts the central policy aims of

the new arrangements, which includes commitments to partnerships, shared

responsibility and mutual obligation.

It is paradoxical for the Government to criticise Indigenous people for being

passive victims and stuck in a welfare mentality yet to continually reinforce a

policy development framework that is passive and devoid of opportunity for

active engagement by Indigenous peoples.

I find it particularly disturbing that there is a lack of acknowledgement of

the importance of Indigenous engagement and participation in policy making. I am

concerned that there is emerging a culture within the federal public service,

led by the Office of Indigenous Policy, which does not place sufficient value

upon such engagement.

This has been particularly notable in debates about reforms to land rights in

the Northern Territory, particularly those relating to changes to land tenure in

townships. The government has stated before the Senate Committee inquiring into

the amendments to the land rights legislation that it is not under an obligation

to consult with Indigenous peoples on the proposed changes, and that that role

lay instead with the land councils in the Northern

Territory.[39]

In subsequent discussions where I have expressed concern about the lack of

community consultation on the issue of town leasing, the OIPC have also noted

that they are not obliged under the legislation to consult with the community,

just with a section of it, that is traditional owners, which the government has

stated could mean just one person in some

instances.[40]

As a matter of practicality, processes for engaging with stakeholders about

proposed reforms are integrally linked to achieving successful implementation at

the community level. It is a mistake to believe that reforms that are developed

in a vacuum will be embraced by communities. It is far more likely that such

reforms will be perceived as disempowering and paternalistic. As a consequence,

governments will face greater difficulties in realising their intended goals.

This will particularly be so if those goals are not shared by Indigenous

communities.

The absence of a national representative body exacerbates this situation.

It is my impression, from discussions with officials in different departments

and agencies and from observing current practices, that government departments

are struggling about how to consult and with who.

As reported in the past two Social Justice Reports, Indigenous peoples

have been giving attention to the necessary components of a replacement national

body for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC).

The National Indigenous Leaders Conference was convened in Adelaide in June

2004 and set out principles that must be met for any national body to be

credible.[41] A smaller steering

committee of participants in that process have met since that initial meeting,

including at a meeting in Melbourne in 2006, to advance their proposal.

To date, there has been limited information made publicly available about

this process or its outcomes. This is unfortunate given the urgent and

compelling need for a national representative body to be in place.

The Social Justice Report 2004 set out a number of options for

ensuring the effective participation of Indigenous peoples in decision making at

the national level. These included the establishment of a national congress of

Indigenous representative organisations, annual meetings of Indigenous service

delivery organisations, and the establishment of a national Indigenous

non-government organisation.[42]

My current assessment of these options is as follows:

- Establishing a national body comprised of the chairpersons of Regional

Indigenous Representative Structures – this is essentially the model

proposed by the ATSIC Review Team in 2004. It is presently not a feasible model

due to the absence of regional representative structures, as discussed in this

chapter. The convening of a national forum should still be treated as a high

priority once regional structures have been established across the country.

- Establishing a National Forum of existing Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peak organisations – This could provide an interim approach

to a more inclusive national representative model. The Forum could be attended

by National Secretariats and State Associations for:

- Indigenous women’s legal

services; - Torres Strait Islander

organisations; - native title organisations and land

councils; - legal services;

- childcare services;

- community controlled health

organisations; - justice advisory committees;

- stolen generations

organisations; - peak Indigenous education

organisations; - networks for CDEP; and

- Job Network providers and so forth.

- Indigenous women’s legal

I would see enormous value in bringing together these

organisations to share common experiences and consider mechanisms for improved

coordination and consideration of issues in a whole of government matter. The

absence of such a coordinated approach from Indigenous organisations (who are

clearly not equipped or resourced to operate in this way) creates a mismatch

between the Government’s new whole of government approach and the ability

of Indigenous peoples to participate in it.A National Forum of Service Providers and peak bodies would be useful as an

ongoing mechanism, but ultimately would not substitute the need for a

representative body to ensure effective engagement with Indigenous

communities.

- Establishing a national non-government organisation of Indigenous peoples – This may well be the result of current consultations being

undertaken by Indigenous peoples. The difficulty that this model will face is

ongoing funding and adequate resourcing. In addition to issues around

establishing a mandate for the organisation, time will need to be devoted to

options for resourcing such a body to ensure that it has the capacity to

undertake the necessary level of activity. Where this model exists

internationally, such as the Assembly of First Nations in Canada, the Indigenous

peoples it represents have a secure land and resource base that assures the

ongoing viability of such a mechanism.

This is, in my view, achievable. Lessons regarding funding

arrangements and structure can be learnt from similar organisations

internationally but also from domestic organisations in other sectors –

such as the Federation of Ethnic Community Councils of Australia and the

Australian Council for Overseas Aid.

The current lack of effective participation of Indigenous peoples at the

national level is a matter of major concern. If the current approach is to

continue unabated, we risk government policy processes entrenching existing

problems of lack of engagement. This will result in systemic problems in

Indigenous policy and service delivery.

Due to my ongoing concerns about this issue, I have identified the following

as a follow up action for my Office over the coming year.

Follow Up Action by Social Justice Commissioner

The Social Justice Commissioner will work with Indigenous organisations and

communities to identify sustainable options for establishing a national

Indigenous representative body.

The Commissioner will conduct research and consultations with

non-government organisations domestically and internationally to establish

existing models for representative structures that might be able to be adapted

to the cultural situation of Indigenous Australians, as well as methods for

expediting the establishment of such a body given the urgent and compelling need

for such a representative body.

Indigenous participation in determining priorities for

inter-governmental cooperation

Concurrent to these developments, the government has continued to bed down

the new arrangements and to confirm changes in policy through processes that do

not include Indigenous participation at the outset. This has primarily occurred

through a new focus on ‘intensive interventions’ and through an

emphasis on setting priorities and agreed areas for action through bilateral

agreements with the states and territories.

Generally speaking, Indigenous engagement is limited to the implementation of

the priorities once they have already been agreed between governments. Chapter 2

of this report discussed the federal government’s movement towards a bilateral interventionist model of ‘strategic interventions’ or

‘intensive interventions’ in some communities designated as being

‘in crisis’.

As noted in chapter 2, the interventionist model puts the strategic

decision-making clearly in the hands of government – the Indigenous

community only becomes involved after the basic decision to intervene has

been made and respective levels of commitment have been agreed between different

governments.

‘Strategic intervention’ in this context in fact means

‘restricted Indigenous participation’ at a governmental and

priority-setting level. Priorities are determined by outsiders (governments),

and only then are the insiders (the community) invited to participate in the

detailed planning and implementation. This does not appear to provide a sound

basis for ‘ownership’ of initiatives undertaken as part of such

strategic interventions.

This approach is more broadly applied through the negotiation of bilateral

agreements on Indigenous affairs between the federal government and the states

and territories.

In general terms, the bilateral agreements commit each government to work in

partnership and in accordance with principles as agreed through the Council of

Australian Governments (COAG). They also include schedules of priority actions

which are agreed solely by governments without Indigenous participation.

In contrast to this lack of engagement prior to the finalisation of the

bilateral agreements, each agreement then commits the Australian government and

the relevant state or territory government to ensure Indigenous participation in

the implementation of the agreement. For example:

- The Bilateral Agreement with the Northern Territory Government: identifies the Northern Territory’s proposed local government reforms

through the creation of Regional Authorities under the NT Local Government

Act 1994 as the main model for Indigenous participation and engagement. As

noted in last year’s Social Justice Report, this is primarily

focused on rural and remote areas and does not address the needs of Indigenous

peoples in urban centres in the Northern Territory. This model is also not

universally accepted by Indigenous peoples in the Territory as the appropriate

mechanism. To address this, the bilateral agrees to consider representational

issues ‘through flexible arrangements (including options that bring

together Indigenous peak

bodies)’[43] although there

have been no developments in progressing this in the past year.

- The Bilateral Agreement with the Queensland Government commits both

governments to ‘work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to

determine community engagement arrangements at the local level’ and to use

the Queensland government’s ‘negotiation table’ process as

‘the key community engagement

mechanism’.[44]

- The Bilateral Agreement with the New South Wales Government: recognises the NSW Government’s Two Ways Together Framework as the

foundation for cooperation between the two governments on service delivery to

Aboriginal communities, including through Shared Responsibility

Agreements.[45]

The NSW Government’s Operational Guidelines for SRAs require

NSW government agencies to satisfy themselves that there has been a proper

consultative process with Indigenous peoples in developing an

SRA.[46]

- The Bilateral Agreement with the South Australian Government: commits

both governments to ‘work with Indigenous people to determine arrangements

for engagement at the local and/ or regional levels’ and in

acknowledgement of the large proportion of Indigenous people who reside in urban

areas in South Australia to ensure that modified arrangements are put in place

for engagement in urban areas.[47] Consistent with this, the South Australian government commenced a four month

consultation process with Indigenous communities in October 2006 to identify an

appropriate structure for a state-wide Aboriginal Advisory

Council.[48] I commend the

Government of South Australia for undertaking this initiative.

- The Bilateral Agreement with the Western Australian Government:

Commits both governments to work with Indigenous people to determine effective

arrangements for engagement, through the conduct of consultations with

Indigenous communities.[49] In

August 2006, the Western Australian government also commenced a consultation

process to identify better ways to engage with Indigenous leaders and to

identify long-term strategies to strengthen the participation of Aboriginal

people in the state’s development. This process is due to conclude by 31

August 2008. [50] I commend the West

Australian Government for undertaking this initiative.

It is unclear how any engagement arrangements agreed at the state

level, such as the processes currently underway in South Australia and Western

Australia, will link to the federal level. It can be expected, however, that

there will be a connection due to the commitments made in the bilateral

agreements. It remains to be seen whether such cooperation is forthcoming from

the federal government once the models freely chosen by Indigenous peoples have

been revealed – particularly if these models extend beyond the acceptable

parameters for the federal government as laid down in their Guidelines for

Regional Indigenous Engagement Arrangements.

It remains unfortunate that priorities have been identified through the

bilateral agreements without Indigenous participation and engagement and that

there continues to be a lack of any mechanism to facilitate Indigenous

participation as the agreed actions for inter-governmental cooperation are

undertaken..

Engagement with Indigenous peoples at the local level

– Indigenous perspectives on Shared Responsibility Agreements

Over the first two years of the new arrangements, there has been considerable

effort devoted to developing Shared Responsibility Agreements (SRAs) with

Indigenous communities and organisations. This stands in marked contrast to the

lack of activity in ensuring the existence of regional mechanisms for Indigenous

participation and engagement.

This section of the report considers what lessons can be learnt from this

local level engagement, particularly in light of the concerns at the

inappropriate mechanisms and processes for engagement that currently exist at

the regional, state and national levels.

Why focus on SRAs?

Considerable emphasis has been placed on SRAs by the Office of Indigenous

Policy Coordination since the inception of the new arrangements.

They have been described as forming one of the beacons of innovation that

they hope will be the hallmark of the new arrangements. SRAs have been

identified as having the potential to open up communities to new streamlined

forms of service delivery that ‘cut red tape’ and address the

longstanding problems of accessibility of mainstream programs, by

‘harnessing the mainstream’. Officers responsible for negotiating

SRAs within regional ICCs are optimistically named ‘solution

brokers’ in accordance with these expectations.

SRAs have also been prominent due to the policy emphasis within them on

mutual obligation: they have been promoted as one of the key approaches for

addressing passivity in communities by instilling a culture of reciprocity,

through mutual obligation for the delivery of services over and above basic

citizenship entitlements.

As such, SRAs provide one of the main tools through which regional Indigenous

Coordination Centres engage with Indigenous communities or organisations at the

local level, alongside the continued administration of existing grant processes.

In both practical terms and also the ‘publicity’ of the new

arrangements, SRAs have occupied an importance that far outweighs the percentage

of expenditure that they represent.

This is the primary reason why there should continue to be detailed attention

and analysis devoted to the effectiveness of this program.

SRAs have emerged out of the COAG trial model and were quickly applied more

broadly prior to that model being evaluated and its particular challenges

identified, such as the high input costs and intensive effort required for

engagement prior to the delivery of services hitting the ground in communities.

The previous two Social Justice Reports have highlighted the

significant challenges for SRAs to meet the expectations placed upon them by the

government – both legal, in ensuring compliance with human rights and

specifically the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth), and practical, in

ensuring sound engagement with Indigenous communities to ensure that the process

can contribute to the long term needs of those communities rather than

distracting attention and effort away from the urgent needs of communities.

As the previous chapter of this report notes, the initial focus on SRAs has

produced only modest outcomes in relation to improving mainstream accessibility.

This has been hampered by limited flexibility at the regional level, with all

SRAs originally having to be sent back to Canberra for approval prior to

proceeding, no matter what level of expenditure was involved.

Similarly, the definitions of and approaches to SRAs have continuously

changed, with current references to ‘single issue’ SRAs,

comprehensive SRAs, holistic SRAs and with the additional blurring of

distinctions between SRAs and Regional Partnership Agreements. This lack of

clarity and singular focus is consistent with the instability that characterises

the new arrangements more than two years into their implementation (and as

discussed in detail in the previous chapter).

There has also been a tendency for particular SRAs to blur the boundaries of

what is acceptable in terms of service provision for basic entitlements to

communities. The application of mutual obligation principles within agreements

has also been problematic on occasion, and has moved away from the initial

intention of supporting communities to become active participants to being

perceived as providing a punitive approach to service delivery.

The Social Justice Report 2005 gave extensive consideration to the

Shared Responsibility Agreement (SRA) making process. It included human rights

guidelines for the process of making SRAs as well as guidelines to guide the

content of SRAs.[51]

The report also identified a number of ‘follow up actions’ that

my Office would undertake over the subsequent period in relation to SRAs. These

included that my Office would monitor the SRA process, including by:

- considering the process for negotiating and implementing SRAs;

- considering whether the obligations contained in agreements are consistent

with human rights standards; - establishing whether the government has fulfilled its commitments in SRAs;

and - consulting with Indigenous peoples, organisations and communities about

their experiences in negotiating

SRAs.[52]

I have continued to monitor SRAs over the past year through a three

stage process.

First, the Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination has forwarded copies of

all SRAs to my Office. This arrangement will no longer be necessary as all SRAs

are now published online on the OIPC website at: http://www.indigenous.gov.au/sra.html.

Second, a national survey was conducted with Indigenous communities and

organisations who had entered into an SRA. My office received many responses to

the survey, and Indigenous people from numerous communities also contacted staff

in my office to discuss their SRA in more detail.

Third, I sought first hand information from Indigenous organisations and

communities by means of interview based case studies. My staff visited some

communities and organisations from which we had received responses through the

survey, and conducted interviews in order to enhance the feedback already

obtained from the surveys. These interviews provide a richer qualitative

sampling of community perspectives on SRAs.

So what then have been the outcomes of SRAs to date for Indigenous peoples, as defined by Indigenous peoples?

This section of the report provides the outcomes of the national survey of

communities who have entered into SRAs as well as of specific case studies which

provide further specific information about the challenges faced during the

negotiation process.

Through both of these processes the purpose was to find out directly from

Indigenous peoples about their experiences and identify whether they were

satisfied with the process. Some of the questions I was interested in asking

through the survey and case studies include:

- Has the community been satisfied with the outcomes of the SRA?

- How did the community come to enter the SRA and how did they find the

process? - Did the service as outlined in the SRA get delivered to the community?

- What supports, if any did the community receive from government?

- What were the critical factors for the community in achieving the objectives

of the SRA? - Has the SRA had longer term benefits – e.g. simplified service

delivery, improved communication with government?

The outcomes of the national survey are discussed first, followed

by the case studies. This section of the report then ends by drawing together

the implications from these to guide the SRA process into the future.

Findings of the national survey of Indigenous communities that have

entered into Shared Responsibility Agreements

- Introduction and Survey methodology

A national survey of Indigenous groupings that had entered into a

SRA was conducted between 4 September 2006 and 15 November 2006. The survey

results reflect the perceptions and understanding of the SRA process by those

Indigenous communities, organisations, families and individuals who had entered

into an agreement.

I invited all communities who had entered into an SRA before 31 December 2005

to complete a survey about the process involved in developing and implementing

their SRA. The cut off date was chosen to ensure that there had been sufficient

time for the SRA to come into effect and for its objectives to be realised.

The survey consisted of 27 questions, with a combination of standard response

questions and open questions to gain contextual qualitative information. All of

the questions gave respondents the opportunity to add their own information.

The survey focused on the content of the SRA, the negotiation process and the

community’s views on the SRA process. The full survey questionnaire is

reproduced as Appendix 3 of this report.

The survey was undertaken on a voluntary basis. Participants were informed

that their responses were to be kept confidential and all responses would be

sufficiently de-identified to preserve their privacy, and in turn enable them to

offer frank feedback on the SRA process.

To increase accessibility for communities and organisations, the survey was

posted on the HREOC website. Each community representative was able to complete

and submit the entire survey online. I sent a letter to the communities before

the survey was posted, explaining why I was interested in conducting the survey

and encouraging communities to participate. Paper copies were also available on

request and my staff also assisted some respondents to complete the survey over

the phone.

The survey sample includes SRAs signed before 31 December 2005. For this

period there were 108 SRAs finalised, involving 124 communities.

In addition to communities that had entered into a SRA prior to 31 December

2005, the Survey results include data relating to a further four SRAs in four

communities who had entered into SRAs in early 2006. These communities had been

referred to the online Survey forms by other communities that had been invited

to submit results.

At the close of the survey, responses had been received relating to 67 SRAs

finalised prior to 31 December 2005, and 71 SRAs in

total.[53]

Based on 67 SRAs, out of a possible 108 SRAs prior to 31 December 2005, the

survey had a 62% response rate. This is considered a very good response rate,

especially given that some of the SRAs were for relatively small projects and

the survey required at least an hour to complete.

In disseminating the survey there was two interesting administrative issues

faced:

- The OIPC and ICC did not have an accurate record of signatories to SRAs. The

OIPC could not identify the relevant contact people for each SRA. This required

working with each regional ICC to identify the relevant organisations or

communities in order to distribute the Survey. During this process, it was not

possible for the ICC or OIPC to identify all signatories to SRAs.

- Some communities refused to participate in the survey on the basis that: a)

the SRA in their community was for such an insubstantial sum of money that they

felt they were already required to over-report and spend too much time in

relation to the agreement; and b) for some communities, the SRA had been

dependent on a particular individual who had left the community since the SRA

was signed. In this situation, some communities stated they had insufficient

knowledge about the SRA to comment on its effectiveness – the SRA clearly

had no relevance or currency in those communities.

- Key Features of SRAs – Survey responses

The greatest numbers of survey respondents were from Western

Australia with 21 responses (32%) and the Northern Territory with 15 responses

(24 %). Respectively, 10 (16%) were from Queensland, 8 (13%) South Australia, 6

(10%) NSW, 3 (5%) Tasmania, and no responses from Victoria. The high response

rates for Western Australia were not surprising given the large number of SRAs

in operation during the survey period.

To understand what type of communities or community organisations have been

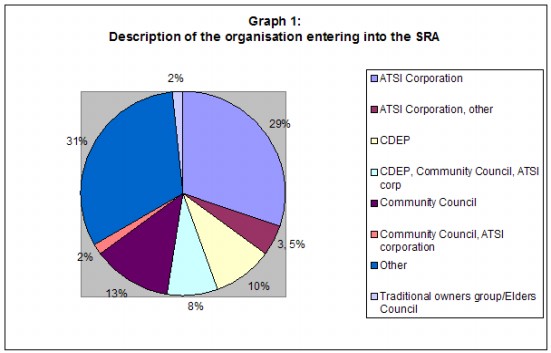

utilising SRAs, the survey asked respondents to describe their organisation. Graph 1 below shows that 29% of the respondents described their

organisation as an Aboriginal/ Torres Strait Islander corporation, and 13% as a

Community Council. A large number of organisations (31%) fell into the

‘other category’. This included a range of organisations including

schools, Aboriginal housing services, charitable trusts, a police unit or other

organisations which fell into a number of different categories.

While the survey did not specifically ask whether the organisation responding

was Indigenous community controlled, 7 schools and 1 police unit completed the

survey in relation to the SRA they had negotiated. In relation to the SRA with

the police unit, further discussions with an Indigenous organisation in that

community which had a specific role in the SRA revealed that they had had no

involvement in its development.

The survey asked respondents to identify what the SRA is about, selecting

from a list of identified categories. The categories were:

- capacity building;

- municipal services;

- sport and recreation;

- health and nutrition;

- community revitalisation;

- cultural activities;

- leadership activities;

- housing;

- economic development;

- family wellbeing;

- law and order and

- other.

Respondents were able to select as many of the subject areas that

they felt applied to their SRA.

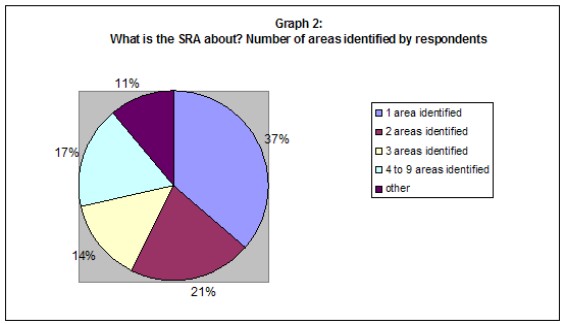

As shown below in Graph 2, 37% of respondents identified a single

category, while the remainder reported that their SRA fell into a number of

different categories. There were no clear patterns arising from how the

communities described their SRAs, which in itself may reveal something about

community perceptions of the SRAs. This may suggest that many communities

perceive the aims of the SRA as much broader than a single issue.

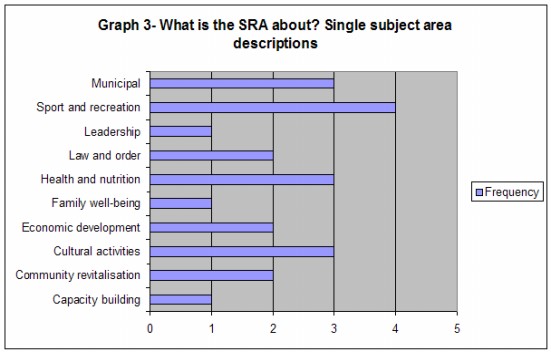

Of those 37% of respondents that were able to categorise their SRA into a

single subject area, Graph 3 shows the spread of SRA subject areas.

As shown in Graph 2, a large number of communities listed more than category

to describe their SRA. Given the unique combinations nominated by respondents no

clear groupings arise but a further breakdown is provided in Table 1 below. Table 1 shows how many communities nominated each category. The most

reported category was ‘other’ (24 respondents), followed by capacity

building and cultural activities (18 respondents).

Table 1: What is the SRA about?

|

Category

|

Frequency

|

|

Cultural revitalisation

|

18

|

|

Capacity building

|

18

|

|

Sport and recreation

|

17

|

|

Health and nutrition

|

16

|

|

Community revitalisation

|

12

|

|

Family wellbeing

|

10

|

|

Leadership

|

10

|

|

Law and order

|

5

|

|

Municipal services

|

6

|

|

Economic development

|

8

|

|

Other

|

24

|

- Obligations contained in SRAs

As SRAs impose obligations on both parties entering into the

agreement, respondents were asked to describe the respective obligations of the

federal government, state governments and community.

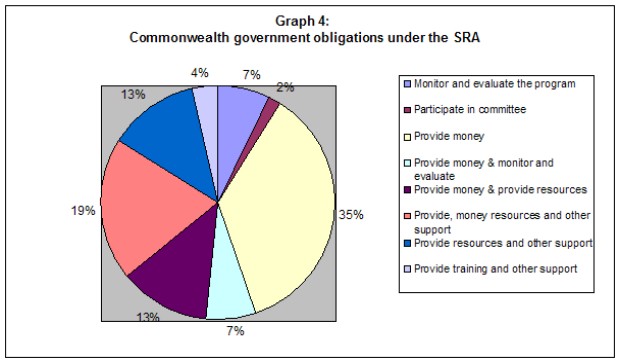

In relation to the federal government, Graph 4 shows that 35% of

communities report that the federal government contributed money to either fund

a salary or a specific project. The next most common obligation (19%) was a

combination of money, resources such as infrastructure, equipment, staff or

consultants and any other form of support.

The range of different federal obligations reported by communities suggests

that at least in principle, the federal government is committing to a greater

range of support mechanisms. This result appears to suggest that through these

SRAs the government is moving away from purely providing funding, to greater

involvement in the actual implementation of a program. This may be through

monitoring and evaluation, provision of resources and infrastructure, as well as

training and participation in steering or other committees.

Given that SRAs are a federal government initiative it is not surprising,

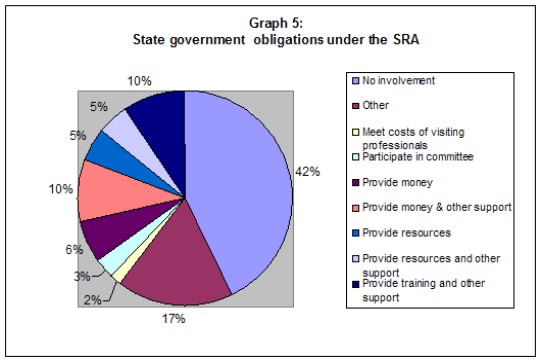

that almost half (42%) of respondents reported no state government involvement

or obligations in the agreement. Graph 5 illustrates the various

obligations of state governments under the SRAs, according to the survey

responses.

The absence of state government participation in many SRAs may reflect the

simple, single issue nature of the SRAs that have been negotiated to

date.[54] As the process becomes

more sophisticated and ‘comprehensive SRAs’ begin to emerge, it is

anticipated that the level of state government involvement will increase.

Some communities reported positive interactions with state governments and

constructive use of state government obligations in SRAs. For instance, one

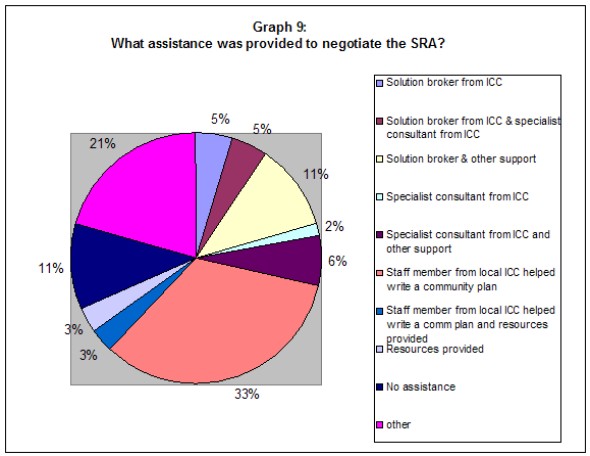

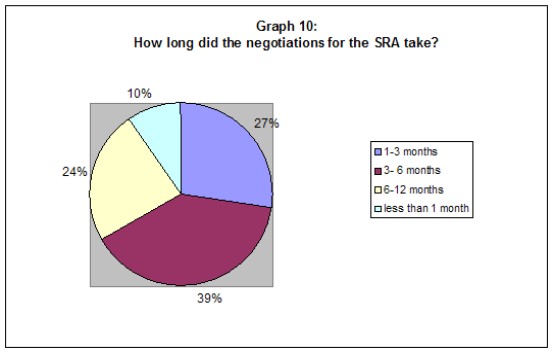

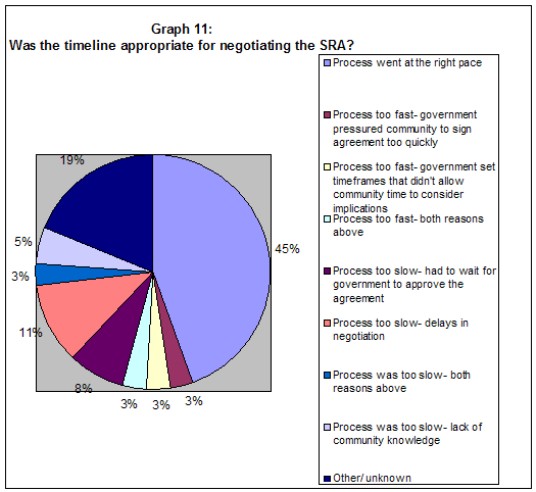

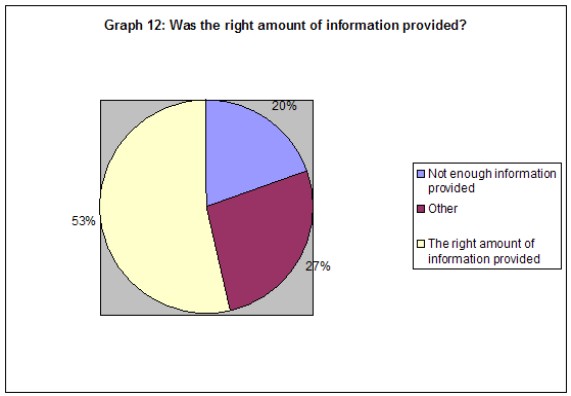

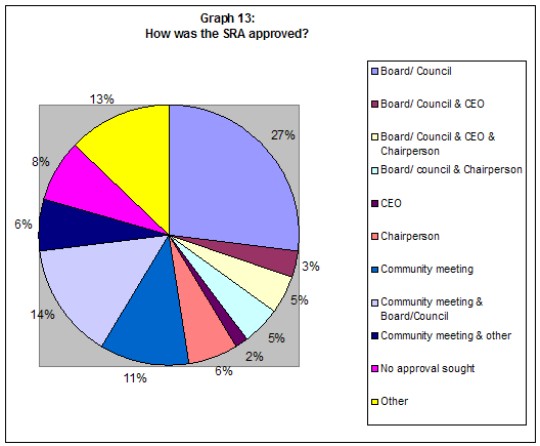

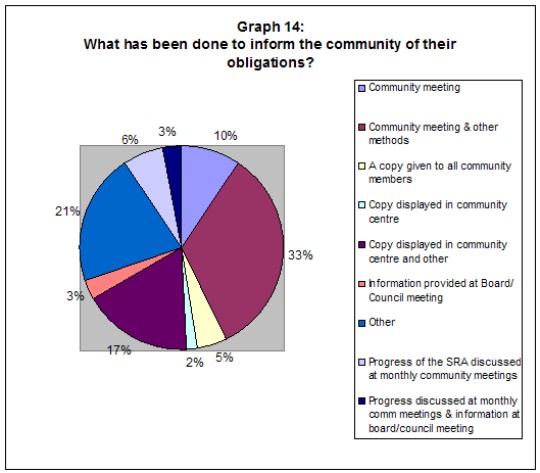

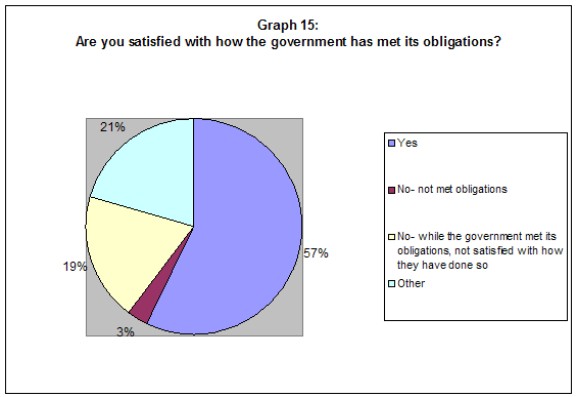

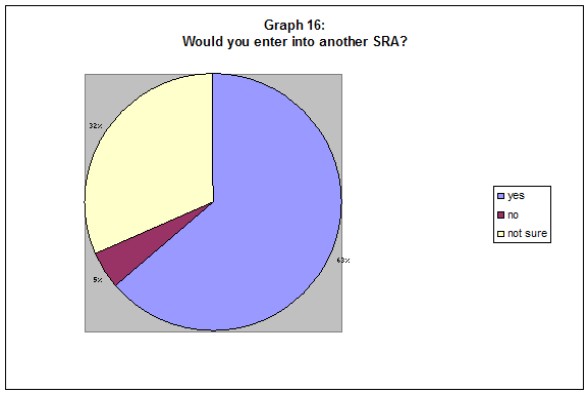

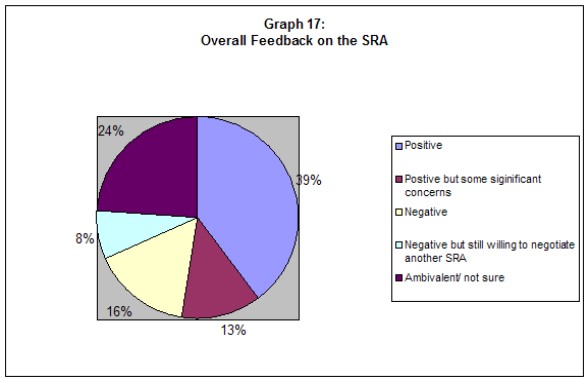

community used the SRA process as an opportunity to develop Memorandums of