Social Justice Report 2004 : Chapter 3 : Implementing new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs

Social Justice Report 2004

Chapter 3 : Implementing new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs

- Part 1: What are the new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs?

- Part II: The implications of the new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs

- Conclusions - Recommendations and follow up actions

- Endnotes

In early 2004, the Federal Government announced that it was introducing significant changes to the way that it delivers services to Indigenous communities and engages with Indigenous peoples. It announced that the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) and its service delivery arm, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services (ATSIS), would be abolished. Responsibility for the delivery of all Indigenous specific programs would be transferred to mainstream government departments. It further announced that all government departments would be required to coordinate their service delivery to Indigenous peoples through the adoption of whole of government approaches, with a greater emphasis on regional service delivery. This new approach is to be based on a process of negotiating agreements with Indigenous families and communities at the local level, and setting priorities at the regional level. Central to this negotiation process is the concept of mutual obligation or reciprocity for service delivery.

These changes have become known as 'the new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs'. The Government began to implement these changes from 1 July 2004. It will be some time, however, before they are fully in place and operational. At present, the new arrangements relate primarily to the delivery of services at the federal level. However, the new arrangements are closely linked to the commitments of all Australian governments through the Council of Australian Governments (or COAG). Accordingly, it can be anticipated that the new arrangements at the federal level are likely to form the basis of inter-governmental efforts to implement COAG's commitments to Indigenous peoples over the coming years.

This chapter considers the preliminary implications of the new arrangements. Since commencing my term as Social Justice Commissioner, I have indicated to governments and to Indigenous peoples that my office will closely monitor the implementation of the new arrangements. I intend that such monitoring will be ongoing given the scope of change being introduced and the potentially wide ramifications of them to Indigenous peoples.

Given the short timeframe in which the new arrangements have been in place, the purpose of this chapter is to identify the main issues that need to be addressed by the Government in implementing the new arrangements.

Part one of the chapter provides an overview of the new arrangements as well as of the factors that led to them being introduced. This material is supported by Appendix One of the report. Part two of the chapter then makes a number of comments about the theory underpinning the new arrangements and practical issues relating to its implementation to date. It also identifies a number of challenges that must be addressed for the new arrangements to benefit Indigenous peoples and communities.

The chapter makes recommendations where there is a need for clear guidance for the process, and otherwise indicates a range of actions that my office will follow up on in monitoring these arrangements over the coming twelve months and beyond.

In preparing this analysis, my office specifically requested information on issues related to the new arrangements. I wrote to each Federal Government department, State and Territory Government and ATSIC Regional Council as well as to the National Board of ATSIC to seek their views in relation to a number of issues about the new arrangements and to obtain information that is not otherwise readily available publicly. I also conducted consultations across Australia with Indigenous communities, Community Councils and organisations, ATSIC Regional Councils as well as with Ministers, senior bureaucrats at the state, territory and federal level, and with staff within the new regional coordination centres who will be implementing these changes.

Part 1: What are the new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs?

There has been a growing momentum over the past two years to change the way governments interact with, and deliver services to, Indigenous people and communities. This culminated with the introduction of the new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs at the federal level from 1 July 2004. This section provides an overview of key developments over the past two years that have shaped the Government's announced changes and then describes the new arrangements and how they are intended to operate. Appendix One to this report provides extracts from key documents which provide further detail about these developments.

Events leading up to the introduction of new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs, 2002 - 2004

There are three main, inter-related developments that have influenced the policy direction of the Government and contributed to the introduction of the new arrangements. These are:

- the focus and scrutiny on the role and performance of ATSIC;

- progress in implementing the commitments of COAG, particularly through the whole of government community trials (COAG trials); and

- an emphasis on change in the Australian Public Service to reinvigorate public administration and improve service delivery.

a) The role and performance of ATSIC

Much of the focus on Indigenous issues in 2003 centred on the performance of ATSIC and proposals for reforming its structure and functions.

The Government announced a review of the role and functions of ATSIC in November 2002. In doing so, the Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (Minister for Indigenous Affairs) stated the commitment of the Government to 'explore the potential for more effective arrangements for ATSIC at the national and regional level' with a 'forward looking assessment which addresses how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can in the future be best represented in the process of the development of Commonwealth policies and programmes to assist them'(1).

The ATSIC Review Team conducted consultations throughout 2003 and released a discussion paper in June 2003. As noted in Appendix One, the Review Team's Discussion Paper found widespread support for the continuation of a national representative Indigenous body but dissatisfaction with the performance of ATSIC. The Review Team's Discussion Paper canvassed a variety of options for achieving a greater emphasis on regional need and participation of Indigenous people at the local level.

At the same time as the ATSIC Review was taking place, there were ongoing debates between the Government and the ATSIC Board about the corporate governance structures and accountability of ATSIC. While the Government initially sought to address their concerns through the introduction of Directions under the ATSIC Act, they were not satisfied with the responsiveness of ATSIC to this. As a consequence, the Government announced on 17 April 2003 that it had decided to create a new executive agency to manage ATSIC's programs in accordance with the policy directions of the ATSIC Board.(2)

The newly created Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services (ATSIS) commenced operations on 1 July 2003. The Minister noted that its creation was to be an 'interim' measure pending the outcomes of the ATSIC Review.

In November 2003, the ATSIC Review Team released its final report, In the hands of the regions - a new ATSIC. The report found that:

ATSIC should be the primary vehicle to represent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples' views to all levels of government and to be an agent for positive change in the development of policy and programs to advance the interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.(3)

They also concluded that ATSIC 'is in urgent need of structural change' and that it:

needs the ability to evolve, directly shaped by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people at the regional level. This was intended when it was established, but has not happened. ATSIC needs positive leadership that generates greater input from the people it is designed to serve. One of its most significant challenges is to regain the confidence of its constituents and work with them and government agencies and other sectors to ensure that needs and aspirations are met. ATSIC also has to operate in a fashion that engages the goodwill and support of the broader community.(4)

The Review Team identified the need to improve the connection between ATSIC's regional representative structures and national policy formulation processes:

As it currently operates, the review panel sees ATSIC as a top down body. Few, if any, of its policy positions are initiated from community or regional levels. The regional operations of ATSIC are very much focused on program management. To fulfil its charter, engage its constituency and strengthen its credibility, ATSIC must go back to the people. The representative structure must allow for full expression of local, regional and State/Territory based views through regional councils and their views should be the pivot of the national voice.(5)

The Report also identified significant challenges for the Government in the delivery of services to Indigenous peoples. The report stated that:

mainstream Commonwealth and State government agencies from time to time have used the existence of ATSIC to avoid or minimise their responsibilities to overcome the significant disadvantage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Because public blame for perceived failures has largely focused, fairly or unfairly, on the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, those mainstream agencies, their ministers and governments have avoided responsibility for their own shortcomings.(6)

There was significant evidence for this finding contained in the 2001 Report on Indigenous funding by the Commonwealth Grants Commission. That report had argued that our federal system of government obscures the responsibilities of different levels of government and has led to cost-shifting between government departments as well as across different governments. When combined with a lack of accessibility of mainstream government programs to Indigenous peoples, they argued that this has placed too much burden on Indigenous specific, supplementary funding mechanisms such as ATSIC. Ultimately, the Commonwealth Grants Commission recommended that the following principles guide service delivery to Indigenous peoples to ensure that programs better aligned funding with need:

- the full and effective participation of Indigenous peoples in decisions affecting funding distribution and service delivery;

- a focus on outcomes;

- ensuring a long term perspective to the design and implementation of programs and services, thus providing a secure context for setting goals;

- ensuring genuine collaborative processes with the involvement of Government and non-Government funders and service deliverers to maximise opportunities for pooling funds, as well as multi-jurisdictional and cross-functional approaches to service delivery;

- recognition of the critical importance of effective access to mainstream programs and services, and clear actions to identify and address barriers to access;

- improving the collection and availability of data to support informed decision-making, monitoring of achievements and program evaluation; and

- recognising the importance of capacity building within Indigenous communities.(7)

The ATSIC Review Team referred to these findings and principles as 'going to the heart of ATSIC's structure and the most appropriate way of delivering government programs and services to Indigenous Australians'(8).

The ATSIC Review Team made 67 recommendations which broadly address issues of the relationship between ATSIC and Indigenous peoples, the Federal Government, the States and Territories, and between its elected and administrative arms.

b) Implementing the commitments of COAG

While the ATSIC Review progressed, all Australian governments continued to implement the commitments that they have made through COAG. Of particular importance in terms of the new arrangements has been the progress made in 2003 and 2004 in the eight COAG whole of government community trial sites. The structures of the new arrangements and the philosophy that underpins them can be seen to have been directly derived from the COAG trials.

The trials have seen governments working together, alongside Indigenous people and communities in the trial sites, with the goal of improving the coordination and flexibility of programs and service delivery so that they better address the needs and priorities of local communities.(9)

The objectives of the COAG trials are to:

- tailor government action to identified community needs and aspirations;

- coordinate government programmes and services where this will improve service delivery outcomes;

- encourage innovative approaches traversing new territory;

- cut through blockages and red tape to resolve issues quickly;

- work with Indigenous communities to build the capacity of people in those communities to negotiate as genuine partners with government;

- negotiate agreed outcomes, benchmarks for measuring progress and management of responsibilities for achieving those outcomes with the relevant people in Indigenous communities; and

- build the capacity of government employees to be able to meet the challenges of working in this new way with Indigenous communities.(10)

Overall, the broader policy context for the COAG trials has been the Federal Government's emphasis on mutual obligation and the responsibility of all players (government, communities, families and individuals) to address issues of social and economic participation.

The philosophy that underpins the trials is 'shared responsibility - shared future'. This approach 'involves communities negotiating as equal parties with government'(11) and acknowledges that the wellbeing of Indigenous communities is shared by individuals, families, communities and government. All parties must work together and build their capacity to support a different approach for the economic, social and cultural development of Indigenous peoples. This partnership approach is formalised in each trial site through the negotiation of a Shared Responsibility Agreement (SRA) between governments and Indigenous peoples.

The Social Justice Report 2003 provided a detailed overview of progress in the eight trial sites up to December 2003. My predecessor as Social Justice Commissioner commented of the trials:

I have noticed an air of enthusiasm and optimism among government departments about the potential of the trials. Government departments are embracing the challenge to re-learn how to interact with and deliver services to Indigenous peoples. There are no illusions among government departments that the trials are as much about building the capacity of governments as they are about building the capacity of Indigenous communities.

Through the active involvement of Ministers and secretaries of federal departments in the trials, a clear message is being sent through mainstream federal departments that these trials matter and that government is serious about improving outcomes for Indigenous peoples. Even at this preliminary stage, this is a significant achievement for the trials. ATSIC have stated that to date 'there has been clear success through improved relationships across governments at trial sites'.

Governments have not turned up in Indigenous communities with pre-determined priorities and approaches... the initial stages have involved building up trust between governments and Indigenous peoples. This has in turn had an impact on relationships within Indigenous communities in some of the trial sites, with an increased focus from Indigenous communities on organising themselves in ways that facilitate dialogue with governments.(12)

While the COAG trials have been underway since 2002 in some sites, and 2003 in others, there has not been a formal evaluation of them as yet. The Indigenous Communities Coordination Taskforce, the body set up to coordinate Federal Government involvement in the COAG trials, released the Federal Government's evaluation framework for the trials in October 2003.(13) Rather than set out what was in place to monitor the trials, the framework set out the key priorities that should be addressed through such a framework once developed. It noted that the development of a simple tracking system was an urgent priority, and should enable governments to:

- provide data on trial site 'projects' and the ability to analyse and monitor these projects using a cross-government approach;

- document how agreement was reached on priorities with communities and the lessons learnt in that process;

- identify innovative and successful approaches and communicate them across other regions; and

- provide feedback to all other parts of the bureaucracies about the implications of new approaches for Indigenous specific and mainstream programs.(14)

A case study of the COAG trials published in April 2004 also stated that 'evaluation of the trials would be premature at this stage'(15). It noted however, that a significant learning from the trials was the importance of leadership through the Australian Public Service in embedding the changes achieved and to ensure that working in a whole of government way becomes the norm.(16) Such leadership and focus has been provided at the federal level through the establishment of a central coordinating agency (the Indigenous Communities Coordination Taskforce), a Ministerial Taskforce to oversee the process and the convening of a Secretaries Group of departmental heads. These processes have been carried over into the new arrangements in a revised form.

Despite the absence of any formal evaluation, the Government has continually stated that the new arrangements are based on the lessons learned from the COAG trials. This issue is discussed further at a later stage of the chapter.

At its meeting of 25 June 2004, COAG also endorsed a National Framework of Principles for Government Service Delivery to Indigenous Australians. This framework confirms, at the inter-governmental level, the principles which underpin the new administrative arrangements at the federal level (and which were developed through the COAG trials). The principles are divided into five thematic groups:

- Sharing responsibility;

- Streamlining service delivery;

- Establishing transparency and accountability;

- Developing a learning framework; and

- Focussing on agreed priority issues.(17)

The principles are set out in full in Appendix One to this report. Agreement to these principles suggests that there will be increased activity to coordinate Federal, State and Territory Government programs and service delivery in coming years. It can be anticipated that the new arrangements at the federal level will be a significant influence on the form of any broadly based inter-governmental coordination.

c) Public sector reform - 'connecting government'

The past eighteen months has seen a number of developments across the federal public sector which have placed increased emphasised on the importance of adopting 'whole of government' approaches and ensuring the effective implementation of government policy.

There has been an increased emphasis on improving the performance of the public sector through the adoption of more holistic processes for public administration. This has variously been described as a whole of government approach, 'joined up' government, or 'connecting government'. It seeks a better integration of policy development and service delivery processes, improved engagement with communities, the development of partnerships and a focus on implementation and achieving results.

Recent developments include the creation in 2003 of the Cabinet Implementation Unit in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, which has a role in coordinating whole of government activity, and the announcement in November 2004 of the creation of a new Department of Human Services to integrate all income support programs formerly undertaken by 6 separate agencies.

The movement towards whole of government approaches across the public service has not received much attention during debates about the introduction of the new arrangements. However, it is important as it places the changes to Indigenous affairs squarely within the broader context of change across the Australian Public Service.

In April 2004, the Management Advisory Committee to the Australian Public Service Commission released a report titled Connecting government: Whole of government responses to Australia's priority challenges. The report observes:

Making whole of government approaches work better for ministers and government is now a key priority for the APS. There is a need to achieve more effective policy coordination and more timely and effective implementation of government policy decisions, in line with the statutory requirement for the APS to be responsive to the elected government. Ministers and government expect the APS to work across organisational boundaries to develop well-informed, comprehensive policy advice and implement government policy in a coordinated way.(18)

Whole of government is defined in this report as:

[P]ublic service agencies working across portfolio boundaries to achieve a shared goal and an integrated government response to particular issues. Approaches can be formal and informal. They can focus on policy development, program management and service delivery.(19)

In launching the Connecting Government report, the Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet stated that 'Whole-of-government is the public administration of the future'. He noted that 'Most of the pressing problems of public policy do not respect organisational boundaries. Nor do most citizens, the subject of public policy.'(20)

In a later speech, he has described the movement towards a whole of government approach as a 'profound' change which could lead to a 'regeneration' of the public service and values which underpin it. He states:

Regeneration, it seems to me, goes beyond familiar arguments about the need for public administration to embrace a process of continuous change to improve performance; to raise the productivity of the public sector; to increase the innovativeness of policy development; and to lift the efficiency, effectiveness and quality of service delivery. It is also about breathing new life into the values and virtues of public service... Regeneration... involves restructuring the organisational framework of public service and reviving its leadership culture.(21)

The Connecting Government report identifies a number of challenges in implementing a whole of government approach. As the Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet notes:

A whole-of-government perspective does not just depend upon the development of policy in a 'joined-up' way or the delivery of policy in a 'seamless' manner. More importantly it depends upon the integration of the two. Operational issues matter. The development of policy and the planning of its delivery are two sides of the same coin... Good policy will always be undermined by poor implementation. Bad policy will always result if it is not informed by the operational experience of those who deliver programmes and services at the front desk, in the call centre or by contract management.

A whole-of-government approach also requires knowledge of how a policy is likely to be perceived by those who are to be affected by it...

The report does not believe that effective solutions lie in moving around the deckchairs of bureaucratic endeavour... Structures alone are not enough. While on occasion the re-ordering of administrative arrangements, and establishment of new bureaucracies, can help focus government on new and emerging issues, the solution to functional demarcations rarely lies in the structures of officialdom. Building new agencies may bring together diverse areas with a common interest and purpose but, in doing so, new silos will emerge...

[The Report] reinforces the need to continue to build an APS culture that supports, models, understands and aspires to whole-of-government solutions. Collegiality at the most senior levels of the service is a key part of this culture. Leadership of the 'whole-of-government' agenda is vital. We are all responsible for driving cooperative behaviours and monitoring the success of whole-of-government approaches...

The report also highlights the need for agencies to recruit and develop people with the right skills.(22)

The Connecting Government report was launched by the Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet less than a week after the announcement of the abolition of ATSIC and the introduction of the new arrangements. The Secretary acknowledged that the new arrangements for Indigenous affairs constitute 'the biggest test of whether the rhetoric of connectivity can be marshalled into effective action... It is an approach on which my reputation, and many of my colleagues, will hang.'(23)

He described the new arrangements as follows:

No new bureaucratic edifice is to be built to administer Aboriginal affairs separate from the responsibility of line agencies. 'Mainstreaming', as it is now envisaged, may involve a step backwards - but it equally represents a bold step forward. It is the antithesis of the old departmentalism. It is a different approach, already piloted in a number of trial sites. Selected by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), eight communities have revealed a glimpse of what can be achieved through collegiate leadership, collaborative government and community partnerships.

The vision is of a whole-of-government approach which can inspire innovative national approaches to the delivery of services to indigenous Australians, but which are responsive to the distinctive needs of particular communities. It requires committed implementation. The approach will not overcome the legacy of disadvantage overnight. Indigenous issues are far too complex for that. But it does have the potential to bring about generational change.(24)

d) Summary

This section and Appendix One to the report provide an overview of the main developments in the lead up to the announcement of the introduction of new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs. Eighteen months ago, the focus at the federal level was very much on reforming the role of ATSIC. The creation of ATSIS was intended as an interim measure to enable ATSIC to strengthen its role as the principle source of policy advice to the Government on Indigenous affairs. As the ATSIS CEO notes, however, ATSIS was tasked with progressing two agendas of the Government:

- to administer programs in accordance with the policies and priorities set by ATSIC and to assist ATSIC to develop a more strategic policy capacity in anticipation of a strengthened role for the Commission in the new arrangements that would flow from the ATSIC Review; and

- to advance the Government's own agenda for innovation and 'best practice' reforms, including coordination with other agencies, the provision of funding based on need and outcomes, and the development of new methods of service delivery.(25)

He notes that 'as the year progressed... Government policy developed to a point where the second agenda overtook and displaced the first' and culminated in the decision of 15 April 2004 'to abolish both ATSIC and ATSIS'(26) and to introduce new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs.

This section also reveals the progressive locking into place of the Federal Government's approach to Indigenous affairs through the processes of COAG, the modelling of whole of government service delivery through the COAG trials and the subsequent movement of Indigenous affairs to the forefront of public sector administrative reform. These developments involve a range of commitments to Indigenous people and identify a number of challenges for government, which I will refer to later in the chapter.

An overview of the new arrangements

This section provides an overview of the new arrangements announced by the Government on 15 April 2004 and how they have been put into place. It reproduces materials from the Government to provide its explanation of the new approach and their expectations of it. The next section then comments on the new arrangements and sets out a number of challenges relating to the proposed new approach.

On 15 April 2004 the Prime Minister and the Minister for Indigenous Affairs announced that the Government intended to abolish ATSIC and ATSIS and embark upon new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs at the federal governmental level. The Prime Minister announced that as a result of the examination by Cabinet of the ATSIC Review report, as well as an extensive examination of Indigenous affairs policy:

when Parliament resumes in May (2004), we will introduce legislation to abolish ATSIC... Our goals in relation to Indigenous affairs are to improve the outcomes and opportunities and hopes of Indigenous people in areas of health, education and employment. We believe very strongly that the experiment in separate representation, elected representation, for Indigenous people has been a failure...

we've come to a very firm conclusion that ATSIC should be abolished and that it should not be replaced, and that programmes should be mainstreamed and that we should renew our commitment to the challenges of improving outcomes for Indigenous people in so many of those key areas.(27)

Details about the new arrangements have progressively been released in the months since this announcement.(28) The various elements of the new arrangements are summarised in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Summary of the new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs

On 15 April 2004, the Government announced that it intended to abolish the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC). The National Board of Commissioners would be abolished from 30 June 2004 and the Regional Councils from 30 June 2005. ATSIC's administrative agency, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services (ATSIS), would also be abolished.

In its place, the Government announced that it would introduce new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs. This involves redesigning the machinery of government and creating new structures to operate in a 'whole of government' manner. The new arrangements are intended to consist of the following elements.

- The transfer of Indigenous specific programs to mainstream government departments and agencies -Programs administered by ATSIS have been transferred to mainstream government departments (with the exception of a few programs that involve the management of ATSIC's assets, which cannot be transferred without the passage of the ATSIC Amendment Act). Funding for these programs is quarantined for Indigenous specific services, which will remain in place.

- Improved accountability for mainstream programs and services -Mainstream services are also expected to be more accessible to Indigenous peoples. The Government has indicated that 'robust machinery' will be introduced to make departments more accountable for their performance and accept their responsibilities.

- The establishment of the Ministerial Taskforce on Indigenous Affairs- Chaired by the Minister for Indigenous Affairs and consisting of Ministers with program responsibilities for Indigenous affairs, the Taskforce is intended to provide high-level direction to the Australian Government on Indigenous policy. It will report to Cabinet on priorities and directions for Indigenous policy, as well as report to the Expenditure Review Committee of Cabinet on program performance and the allocation of resources across agencies.

- The establishment of the Secretaries Group on Indigenous Affairs- Composed of all the Australian Government Departmental Heads and chaired by the Secretary of Prime Minister & Cabinet, it will support the Ministerial Taskforce and report annually on the performance of Indigenous programs across government.

- The establishment of a National Indigenous Council - An appointed council of Indigenous experts to advise the Government on policy, program and service delivery issues, the Council will meet at least four times per year and will directly advise the Ministerial Taskforce. It is not intended to be a representative body, and members have been chosen for their individual expertise.

- The creation of an Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination (OIPC) - Located within the Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, it will coordinate Federal Government policy development and service delivery in Indigenous affairs on a whole of government basis.

- Movement to a single budget submission for Indigenous affairs - Under the new arrangements, all departments will contribute to a single, coordinated Budget submission for Indigenous-specific funding that supplements the delivery of programs for all Australians.

- The creation of regional Indigenous Coordination Centres (ICC's) - Will be part of the OIPC and will coordinate the service-delivery of all federal Departments at the regional level, as well as negotiate agreements with Indigenous peoples and communities at the regional and local level. ICC's have been described as 'the Australian Government's presence on the ground' offering 'a simple, coordinated and flexible... service'(29).

- The negotiation of agreements with Indigenous peoples at a regional and community level - The ICC's will negotiate Regional Participation Agreements setting out the regional priorities of Indigenous peoples, as well as Shared Responsibility Agreements at the community, family or clan level. These agreements will be based on the principle of shared responsibility and involve mutual obligation or reciprocity for service delivery.

- Support for regional Indigenous representative structures -The Government has indicated that it will look to support Indigenous representative structures at the regional level in place of ATSIC. Such structures may vary between regions. It is anticipated that ICC Managers would negotiate a Regional Participation Agreement outlining the priorities in that region with the representative body.

- A focus on implementing the commitments of the Council of Australian Governments (COAG))- The commitments of COAG to addressing Indigenous disadvantage will form the framework for the delivery of services and policy development on Indigenous affairs. The new approach also means working constructively with states, territories and local government in achieving a true 'whole of government' approach.

- Impact of changes on Torres Strait Islander peoples - The Torres Strait Regional Authority, which operates in the Torres Strait Islands region, is unaffected by the new arrangements. The Torres Strait Islander Advisory Board, which advises the Government on issues specific to Torres Strait Islanders on the mainland, will be abolished through the ATSIC Bill. The needs of Torres Strait Islanders living on the mainland are expected to be met through the operation of ICC's.

A detailed overview of the Government's announcements on each of these issues is provided in the chronology of events in Appendix One to this report. In essence, the new structures and approaches to be introduced through these arrangements can be grouped into six main components. They are:

- The abolition of ATSIC and ATSIS. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Amendment Bill 2004 (Cth) was introduced to the Federal Parliament on 27 May 2004 to achieve this. It passed through the House of Representatives on 2 June 2004 but has not yet been passed by the Senate. Instead, the Bill was referred to an inquiry by the newly created Senate Select Committee on the Administration of Indigenous Affairs. The report of the Committee will be presented in March 2005. Unless and until the Bill is passed by the Senate, ATSIC continues to exist - albeit with few program responsibilities and limited funding. ATSIS continues to exist in a skeleton form to assist ATSIC in the administration of programs that cannot be disbursed until the passage of the ATSIC Bill.

- The transfer of Indigenous specific programs to mainstream departments. The Government noted on 30 June 2004 that 'more than $1billion of former ATSIC/ATSIS programs have been transferred to mainstream Australian Government agencies and some 1300 staff commence work in their new Departments as of tomorrow'(30). The emphasis of this mainstreaming is on better coordination of programs and services within and between agencies, and the development of a coordinated and flexible approach to resource allocation on Indigenous issues. This is intended to involve developing ways to use funds more flexibly-for example, by pooling funds for cross-agency projects or transferring them between agencies and programs so they better address the needs and priorities of communities. The single budget submission for Indigenous affairs will promote this approach.

- Leadership and strategic direction from a 'top down' and 'bottom up' process. The new arrangements are driven from the 'top down' by the Ministerial Taskforce, National Indigenous Council, Secretaries Group and Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination (OIPC). They are also informed by a 'bottom up' approach through the regional ICC's (as managed by the OIPC) and the intended involvement of Indigenous peoples at the community level (through Shared Responsibility Agreements) and on a regional basis (through regional representative structures and Regional Participation Agreements). The Government has stated that 'Leadership, strategy and accountability will be provided at the top of the structure, but these same qualities will be emphasised at the local and regional level in active partnership with Indigenous people'(31).

-

Coordination at the national and regional levels. The OIPC is intended to be the national level coordinator while each ICC is intended to be the community and regional level coordinator of all Australian government activity. OIPC will be responsible for coordinating whole of government policy, program and service delivery across the Australian Government; developing new ways of engaging with Indigenous people at the regional and local level; brokering relationships with other levels of government and the private sector; reporting on the performance of government programs and services for Indigenous people to inform policy review and development; managing and providing common services to the ICC network; and advising the Minister and Government on Indigenous issues.(32) The OIPC also has a state office in each State and Territory to coordinate activities at the state level.

ICCs will coordinate the service-delivery of all federal departments at the regional level. They are intended to provide Indigenous people and communities with a single point of contact with Australian government departments. The Government has described each ICC as a whole of Australian government office, with staff from multiple agencies, headed by a manager who is the focal point for the engagement with stakeholders and who is responsible for coordinating the efforts of all agencies in their dealings with clients on a whole of government basis.(33)

-

Participation and engagement of Indigenous peoples. The Government states that 'better ways of representing Indigenous interests at the local level are fundamental to the new arrangements'(34). ATSIC Regional Councils are intended to fulfill this role until their abolition on 30 June 2005. The Government then intends to work collaboratively with regional Indigenous representative structures. They have stated that 'During 2004-05 the Australian Government will consult Indigenous people throughout Australia, as well as State and Territory Governments, about structures for communicating Indigenous views and concerns to government and ensuring services are delivered in accordance with local priorities and preferred delivery methods'(35). These regional structures will also negotiate with government on Regional Partnership Agreements (RPAs).

The Government will also negotiate Shared Responsibility Agreements at the local level with Indigenous families, clans or communities. These agreements will 'set out clearly what the family, community and government is responsible for contributing to a particular activity, what outcomes are to be achieved, and the agreed milestones to measure progress. Under the new approach, groups will need to offer commitments and undertake changes that benefit the community in return for government funding'(36).

- Working collaboratively with the states and territories. The Government acknowledges that to achieve a true whole of government approach it will need to work constructively with the States and Territories and local government. The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) and the commitments made through it, will remain the main strategic forum for advancing such collaboration.

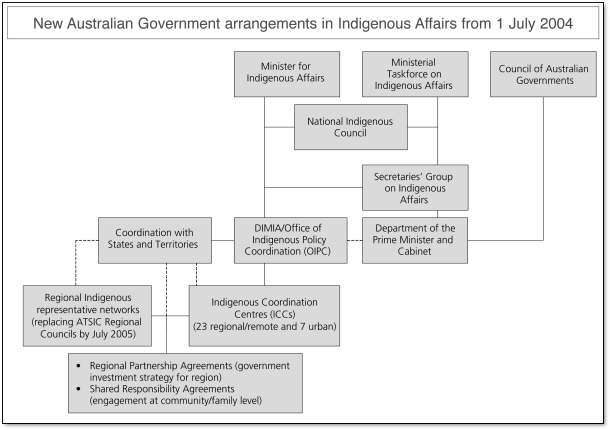

Figure 1 below shows how these components and new structures are intended to fit together.

Figure 1: New Australian Government arrangements in Indigenous affairs from 1 July 2004(37)

The new arrangements are also underpinned by five guiding principles. The Government has described these as follows.

Table 2: Principles underpinning the new arrangements for Indigenous affairs(38)

1. Collaboration - All Australian Government agencies are required to work together in a coordinated way.

This collaboration will be reflected in a framework of cooperative structures that stretch from top to bottom: from the Ministerial Taskforce and Secretaries' Group in Canberra to a network of regional offices around the nation. The foundation will be negotiated Framework Agreements, through which government and community work as partners to establish their goals and agree their shared responsibilities for their achievement.

Under the direction of the Ministerial Taskforce, agencies will also collaborate on the design of whole-of-government policy initiatives and proposals for the redirection of resources to priority areas and to ways of working that have demonstrated their effectiveness in achieving better outcomes for Indigenous people.

2. Regional need - The new mainstreaming will focus on regional need.

ICCs will work with regional networks of representative Indigenous organisations to ensure that local needs and priorities are understood. ATSIC Regional Councils will be consulted and, over time, ICCs will work in partnership with a cross-section of representative structures that local Indigenous people decide to put in place. Together they will shape Australian Government engagement and strategies in a region including Regional Partnership Agreements (RPAs) and Shared Responsibility Agreements (SRAs) at the community or family level.

Integration with the activities of State/Territory and local governments is also fundamental to achieving local outcomes and this is being pursued through bilateral agreements. In likelihood, there will be different consultative and delivery mechanisms negotiated in different States and Territories.

3. Flexibility - Program guidelines will no longer be treated as rigid rules, inhibiting innovation-though flexibility will not be introduced at the expense of due process.

Over time ways will be developed to allow funds to be moved between agencies and programs, to support good local strategies and whole-of-government objectives. Each year Ministers will bring forward a coordinated Budget submission for Indigenous-specific funding that supplements the delivery of programs for all Australians. The single Budget submission will be informed by experience at the regional and local level, advice from Indigenous networks and the professional expertise represented on the National Indigenous Council.

4. Accountability - Improved accountability, performance monitoring and reporting will be built into the new arrangements.

The Ministerial Taskforce, advised by the National Indigenous Council, will make recommendations to the Australian Government on priorities and funding for Indigenous Affairs. The Secretaries' Group will prepare a public annual report on the performance of Indigenous programs across government. OIPC will have a strong performance monitoring and evaluation role relating to the new whole-of-government arrangements.

Departmental Secretaries will be accountable to their portfolio Ministers and the Prime Minister for Indigenous-specific program delivery and cooperation with other parts of the Australian Government, State/Territory Governments and Indigenous communities, as part of their performance assessments. Indigenous organisations providing services will be required to deliver on their obligations under reformed funding arrangements that focus on outcomes.

5. Leadership - Strong leadership is required to make the new arrangements work, both within government and from the networks of representative Indigenous organisations, at regional and local levels.

Within the Australian Government, relevant Ministers and departmental heads will take responsibility, individually and collectively, at a national level for working with communities in a whole-of-government manner. ICC Managers will be responsible at the regional level.

The representative networks that Indigenous people decide to establish at the local and regional level will provide leadership and be accountable to local people. Where leadership capacity needs to be strengthened, the Australian Government will provide support.

The next section of the report considers the nature of the commitments that the Government has made through the introduction of these new arrangements and how they are going about implementing their commitments. It also identifies a number of challenges that must be addressed for these new arrangements to benefit Indigenous peoples and communities.

Part II: The implications of the new arrangements for the administration of Indigenous affairs

The new arrangements that have been announced by the Government for the administration of Indigenous affairs are complicated and wide-ranging. The Government began to implement the arrangements from 1 July 2004. It is clear that the various components of the new arrangements were not finalised at that time and have continued to be developed as the arrangements have been introduced. It will be some time before the machinery of government changes required by the Government's announcements are fully in place and it will be longer still until the changes impact at the community level.

Since commencing my term as Social Justice Commissioner, I have indicated to governments and to Indigenous peoples that my office will closely monitor the implementation of the new arrangements. I intend that such monitoring will be ongoing given the scope of change being introduced and the potentially wide ramifications of them to Indigenous peoples.

On this basis, in September 2004 my office specifically requested information on issues related to the new arrangements. I wrote to each Federal Government department, State and Territory Government and ATSIC Regional Council as well as to the National Board of Commissioners of ATSIC to seek their views in relation to a number of issues about the new arrangements and to obtain information that is not otherwise readily available publicly.(39)

I also conducted consultations across Australia with a variety of Indigenous communities, organisations and community councils, ATSIC Regional Councils and Commissioners, as well as with Ministers and senior bureaucrats at the state, territory and federal level, and with staff within the new regional coordination centres who will be implementing the changes.(40) These consultations were preliminary in nature. From them I intended to gain a sense of what information was available in regions about the new arrangements as well as the initial response and concerns about the new processes.

This section of the chapter reflects on this material and identifies a number of issues and challenges that the new arrangements raise. It makes recommendations where there is a need for clear guidance for the process, and otherwise indicates a range of actions that my office will focus on specifically in monitoring these arrangements over the coming twelve months and beyond.

Before considering the specific challenges that are raised by the new processes which are to be set into place, I have a number of global comments about the implications of the Government's announcements and the implementation of them to date. These comments relate to the theory and objectives that underpin the new arrangements, as well as to practical matters relating to how the new arrangements have been implemented in the first few months.

Comments about the theory underpinning the new arrangements

- The new arrangements contain a number of significant innovations for the delivery of federal programs and services

The new arrangements will see the introduction of significant changes to the processes through which the Australian Government develops policy and programs and delivers services to Indigenous people and communities. The scope of this change is perhaps unprecedented in the administration of Indigenous affairs at the federal level. This reality has not been understood by many people to date.

As the Minister for Indigenous Affairs recently stated:

A quiet revolution has been underway since 1 July 2004 involving a radical new approach... Nothing short of revolutionary reform is required if we are turn around the appalling indicators of Indigenous disadvantage and the sense of hopelessness that many Indigenous people face every day.(41)

The new arrangements contain a number of significant innovations for the delivery of federal programs and services.

First, the new arrangements compel engagement on Indigenous issues at the most senior levels of the government and public service. The main innovations supporting this are the establishment of the Ministerial Taskforce on Indigenous Affairs and the Secretaries Group on Indigenous Affairs to lead the process, as well as the introduction of a single budget submission for Indigenous Affairs.

These mechanisms provide leadership and unambiguous guidance to all public servants that addressing Indigenous disadvantage is no longer somebody else's problem (such as ATSIC), but rather is a routine responsibility of all public servants.

They also provide the potential to 'bust' through bureaucratic tangles where demarcations between programs and departments have in the past hindered results being achieved and innovative solutions being trialed. The Ministerial Taskforce and Secretaries Group have significant leverage in seeking to ensure that administrative barriers do not continue to defeat innovation or the adoption of more holistic responses to the needs of Indigenous people and communities.

Second, the new arrangements provide much potential for improving government coordination. The creation of Indigenous Coordination Centres, bringing together departments responsible for the delivery of mainstream and Indigenous specific programs in regional locations, as well as the creation of the Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination to provide national coordination are significant innovations.

In the past, government simply hasn't had the mechanisms to implement approaches based on regional need. Government programs tend to have been set up on a statewide basis rather than in regions, and many government departments have had limited or no presence outside of capital cities. The main finding of the Commonwealth Grants Commission's landmark Report on Indigenous Funding was the inability of government processes to identify or respond to regional need or to allocate funding on the basis of greatest need.

These inabilities have existed despite ATSIC Regional Councils having developed regional plans which seek to identify regional priorities and the ATSIC National Board and Regional Councils also having had decision making powers to allocate funding regionally. These decision making processes, however, have been limited to Indigenous-specific funds administered by ATSIC and lately by ATSIS. Regional plans have also generally not been followed by mainstream departments and State or Territory Governments.

The existence of ICC's in regional areas, staffed by representatives of relevant government departments, provides a very practical step in seeking to overcome the problems that have existed up until now in this regard. The oversight role of the OIPC (and of the ICC Managers, who are OIPC staff) also provides a practical way of seeking to ensure consistency between regions as well as a focal point for sharing best practice and building on the success in individual regions. The interested gaze of the Ministerial Taskforce and the Secretaries Group will also encourage individual departments to work on a collegiate basis within the ICC structure.

The role of the OIPC at a national level is also significant. There has, in the past, been a variety of national offices to provide advice on Indigenous policy (often in conflict with ATSIC). The predecessors of the OIPC have not, however, had a role as wide-ranging as that of the OIPC nor the leverage to promote a more integrated approach to Indigenous service delivery between departments. The leverage of OIPC is drawn from its relationship to the Ministerial Taskforce and Secretaries Group, as well as its coordination role in ICC's.

Third, the new arrangements have the potential to address the longstanding problem of under-performance and inaccessibility of mainstream programs for Indigenous peoples. This is a clear objective of the new arrangements that have been set out by the Government in their announcements. The challenge of achieving this is discussed further below.

Fourth, the new arrangements, once implemented, also have the potential to provide workable solutions to the century old problem of delivering services in a federal system. This will depend, of course, not only on the successful implementation of the new arrangements federally but also their coordination with systems in the states and territories. This challenge is also discussed further below.

It is notable, however, that the principles that underpin the new arrangements at the federal level were recently adopted by all Australian Governments at the meeting of the Council of Australian Governments in June 2004. As set out in Appendix One, the National framework of principles for government service delivery to Indigenous Australians commit all governments to agree upon appropriate consultation and delivery arrangements between the Commonwealth and each State and Territory.

It is difficult to argue against the objectives that the new arrangements are designed to meet. They contain a number of machinery of government changes that, in theory, are innovative in how they seek to address longstanding difficulties of government service provision to Indigenous people and communities.

- The new arrangements involve the making of significant commitments to Indigenous peoples

These changes to the machinery of government are accompanied by significant commitments to Indigenous peoples.

At a general level, in announcing the new arrangements and the abolition of ATSIC the Minister for Indigenous Affairs stated that:

The Government has been concerned for some time that while there has been progress that it has been too slow and a new approach is essential. The new approach is based on all of us accepting responsibility...

For too long we have hidden behind Indigenous programmes and organisations... It is recognised that existing mainstream programmes need to perform better for Aboriginal people and we will therefore put in place robust machinery to ensure that mainstream agencies accept their responsibilities and are accountable for outcomes...

Our focus will continue to be on better service and better outcomes for Indigenous people.(42)

In re-introducing the ATSIC Amendment Bill to Federal Parliament in December 2004, the Minister also stated that 'the amount of money can no longer be the benchmark - outcomes must be the measure'(43).

The commitment to be held accountable for improving outcomes in addressing Indigenous disadvantage is supported by two main developments over the past year. First, the Government has identified as its priority tasks those issues that are included in the National Reporting Framework for Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage as developed by the Steering Committee for Government Service Provision. The Government has also agreed to this framework and by doing so has provided a simple mechanism for measuring progress in addressing its commitments over time. Second, the newly constituted Ministerial Taskforce on Indigenous Affairs has adopted a Charter which contains the Government's 20-30 year vision.

This Charter is set out in full in Appendix One to this report. It states, in part, that:

The Ministerial Taskforce will set the long term agenda, determining the Australian Government's vision for Indigenous affairs, in 20-30 years, and focussing urgently on the strategies that need to be put in place now to achieve improved outcomes, recognising that:

- despite the significant commitment of governments of all persuasions over a long period, progress on key indicators of social and economic well being for Indigenous Australians has only been gradual; and

- to make better progress there must be inter-generational change.

The following statement encapsulates the Taskforce's long term vision for Indigenous Australians:

'Indigenous Australians, wherever they live, have the same opportunities as other Australians to make informed choices about their lives, to realise their full potential in whatever they choose to do and to take responsibility for managing their own affairs'.

The Ministerial Taskforce is determined to create the best possible policy environment in which this can be achieved.

In determining key priorities for urgent action it will be guided by the Productivity Commission's Report on Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage, commissioned by COAG, in particular it seven Strategic Areas for Action:

- early child development and growth (prenatal to age 3);

- early school engagement and performance (preschool to year 3);

- positive childhood and transition to adulthood;

- substance use and misuse;

- functional and resilient families and communities;

- effective environmental health systems;

- economic participation and development.(44)

The next section of the report identifies the introduction of adequate monitoring and evaluation processes, as well as benchmarking to identify adequate rates of progress, as significant challenges to be faced under the new arrangements. These issues must be treated as fundamental components of the machinery of government if the new arrangements are to result in any practical improvements in the lives of Indigenous peoples.

At this point, however, I wish to acknowledge that sincere commitments have been made by the Government to address Indigenous disadvantage and are based on a frank acknowledgement that a continuation of previous approaches would not result in sufficient rates of change or improvement. Time will tell if these words can be turned into action and results.

- The new arrangements are a continuation of the Government's approach to Indigenous affairs

While the new arrangements involve significant and radical change to the processes of government, they remain entirely consistent with the Government's 'practical reconciliation' approach. The Ministerial Taskforce Charter on Indigenous Affairs makes this clear. It states:

In announcing the new Indigenous affairs arrangements on 15 April 2004, the Prime Minister signalled that the Government's goals are 'to improve the outcomes and opportunities and hopes of Indigenous people in areas of health, education and employment.' The Prime Minister had previously committed the Government to addressing Indigenous family violence as a priority.

The Ministerial taskforce will focus on practical measures such as these and other related issues such as economic development, safer communities, law and justice.

However, the taskforce recognises the importance to Indigenous people of other issues such as cultural identity and heritage, language preservation, traditional law, land and 'community' governance.

- These are issues on which Indigenous people themselves should take the lead, with government supporting them as appropriate.(45)

When asked why he considered ATSIC had failed, the Prime Minister stated that:

it has become too preoccupied with what might loosely be called symbolic issues and too little concern with delivering real outcomes for Indigenous people... our greatest obligation is to give indigenous people a greater opportunity to share in the wealth and success and the bounty of this country, and plainly the arrangements that have existed in the past do not deliver that.(46)

Previous Social Justice Reports have expressed concern at the narrowness of the philosophy that underpins this approach and the distinction it creates between issues that have been termed practical as opposed to those described as symbolic.

I note that through the new arrangements, the Government has made commitments to work in partnership with Indigenous people and communities, including through regional representative structures and at the local level. The Government will also be advised by the National Indigenous Council, the terms of reference of which include alerting the Government to 'current and emerging policy, programme and service delivery issues' and promoting 'constructive dialogue and engagement between government and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, communities and organisations'. (47)

The relationship with the Government through these processes should not be limited only to those issues to which the Government is committed. They should enable a respectful exchange of views, including the identification of issues and priorities by Indigenous peoples which may differ from those identified by the Government. Time will tell whether the new arrangements operate in such a way, or alternatively whether they will result in a more constrained and limited policy framework.

- The new arrangements are based on lessons learned from the COAG trials. These lessons are preliminary and require ongoing consideration.

The Government has stated that the new arrangements are based on 'the early learnings' from the COAG whole of government community trials as well as the principle findings of the ATSIC Review.(48) Key aspects of the new arrangements - for example, the Ministerial Taskforce; Secretaries Group; establishment of a central coordinating agency; and Shared Responsibility Agreements - have their origins in the COAG trials.

The Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination states:

The COAG Trials are continuing. However, there are a number of examples of lessons from the first eighteen months of the trials (ie, prior to the announcement of the new Indigenous Affairs arrangements in April 2004), including the need for:

- strong, systemic and demonstrable leadership and commitment from the top of government and the bureaucracy;

- from the Australian Government's perspective, this was provided by COAG and the Secretaries Group.

- more effective coordination arrangements to allow for a whole-of-government approach;

- improved accountability, performance monitoring and reporting;

- the development of new ways of engaging directly with indigenous Australians at the regional and local level to promote inclusiveness and avoid 'gate-keeping';

- the development of government skills in whole-of-government approaches and improved engagement with indigenous Australians - building government capacity to work in a new way; and

- more flexible and responsive funding arrangements.

Other key lessons include:

- effective implementation of shared responsibility principles is crucial if sustainable change is to be achieved;

- the importance of building trust between government and community and following through on commitments;

- the critical importance of building capacity and effective governance in communities;

- the importance of striking a balance between driving change and allowing change to happen at an appropriate pace that will enable it to be sustainable; and

- acknowledgement that sustainable change will only occur over the long term and the related need for government to commit to working with communities for the long term.(49)

These lessons are important. As noted above, they have provided guidance as to steps that can be taken to put a whole of government approach into operation.

The lessons are, however, preliminary and at a conceptual level. They indicate the key issues that must be addressed in implementing a whole of government approach. They do not provide solutions or proven approaches that can be applied to Indigenous communities across the country.

At the time that the new arrangements were announced there had not been any formal evaluation of the COAG trials. Indeed as recent as the end of 2003, the mechanisms necessary for such an evaluation process - including through the establishment of an integrated database - were still not in place.

ATSIC expressed significant concern to the Social Justice Commissioner in 2003 about the absence of a monitoring framework for the trials. They stated:

The Commission is particularly concerned that a comprehensive national evaluation strategy is not in place. This is likely to lead to unclear judgements later on, as the starting point for assessing change has not been clearly established. In addition, the Commission is concerned that there is no commitment to an independent evaluation of the initiative. The reliance on a systems-based internal evaluation strategy might not provide the most objective perspective on the successes and failures of the initiative, and may produce an inadequate basis upon which to make long term policy and program reforms.(50)

The Indigenous Communities Coordination Taskforce, the coordinating agency at the federal government level for the COAG trials, produced a draft document for consideration by the Secretaries Group in early 2004 - titled 'Lessons Learned' - but it was never released publicly. During the consultations for this chapter, we heard concerns that some of the preliminary findings of that document were not sufficiently accounted for in the formulation of the new arrangements.

Concerns have also been expressed about progress in some of the trial sites. For example:

- In April 2004, the Western Australian Coroner expressed concerns about the lack of government coordination in the East Kimberley Trial Site and consequent inaction by governments in addressing problems of petrol sniffing in Balgo.(51)

- The Shadow Attorney-General of South Australia has also expressed concerns about selective consultation by governments with Indigenous people and communities on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara trial site.(52)

- In consultations for this report, staff of Australian government agencies involved in one trial site stated that there was confusion about the 'shared responsibility' approach and the purposes of Shared Responsibility Agreements.

- In another trial site, both staff of the lead Australian government agency and ATSIC Regional Councillors stated that Indigenous people have had very little input into the whole of government activity in that trial site to date and that there was a risk that the trial may reinforce existing problems of corporate governance in communities by only consulting with community councils and not the community more broadly.

- In a further trial site, a range of bodies and community members expressed the view that the achievements in the trial site had not been the result of whole of government activity but instead of the focussed implementation of programs of the Commonwealth Government's lead agency for the trial site (resulting in the benefits of coordination through the trial being overstated).

- Concern has been expressed in the Shepparton trial site, in Victoria, about the lack of appropriate engagement of traditional owners of the region in the trial. The Reference Group in Shepparton is composed of representatives of Indigenous service delivery organisations rather than involving the broader Indigenous community.(53) It was stated that this has resulted in the process for engaging with Indigenous peoples in the trial being too focused on engaging with service delivery organisations with the consequence that certain family groups were over-represented whereas other family groups were not represented at all. A number of different groups have stated that this has led to increased tensions within the community.(54) The Commonwealth's lead agency for the COAG site acknowledges that there have been problems in engaging with the community and are taking steps to seek to rectify this situation.

- Concern was also expressed that the consultation mechanisms established in the Shepparton trial site were being used by service delivery agencies to 'bid' for extra funding and to have other funding reallocated to their organisations.

ATSIC also expressed concern to my predecessor in late 2003 about progress in the trial sites. ATSIC stated that:

- There had been limited experimentation of new approaches by Lead Agencies in the trials, as they struggled to balance different priorities with trial partners leading to difficulties in progressing joined-up projects on the ground;

- As a consequence of this, programs that are used more flexibly tend to be Indigenous-specific rather than mainstream;

- There had been a blurring in some instances of Commonwealth and state responsibilities, attracting the possibility of cost shifting between parties compounded by the inexperience of lead agencies and their personnel when engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities; and

- Initiatives in one trial were not being identified as having potential application in other trials.(55)

In its' submission to the Senate inquiry into the ATSIC Amendment Bill, the Victorian Government has urged caution in basing new arrangements on the preliminary outcomes of the COAG trials:

Although the COAG trials are progressing well, it is too early to determine whether the trials should form the basis of a new model of service delivery in Victoria or wider Australia... It is premature to build on the COAG trials given they are still in their developmental phase and are based on disparate models of operation across diverse jurisdictions.(56)

By reproducing these materials I do not intend to suggest that it is inappropriate to base the new arrangements on the lessons of the COAG trials. What these comments reveal, however, is that the experiences of governments in the trials remain preliminary and it is not possible to state definitively that the lessons from them can translate into longer term change or even provide transferable solutions.

In light of the practical matters that have arisen as a result of the introduction of the new arrangements, as discussed in the next section, perhaps a more gradual and formal change management strategy should have been utilised in introducing the new arrangements. For example staggering the introduction of the new arrangements (such as by region) may have provided the opportunity to test the transferability of the preliminary lessons of the COAG trials.

Nevertheless, there remains a need for thorough and ongoing evaluation of the outcomes of the COAG trials, as well as rigorous monitoring of the implementation of the new arrangements. This is particularly important so as to address any teething problems that may emerge through the implementation of the new arrangements to ensure that they do not become systemic problems in the future.

Follow up action by Social Justice Commissioner

1. In light of the importance of the lessons from the COAG whole of government community trials for the implementation of the new arrangements, the Social Justice Commissioner will over the coming twelve months:

- Consider the adequacy of processes for monitoring and evaluating the COAG trials;

- Consult with participants in the COAG trials (including Indigenous peoples) and analyse the outcomes of monitoring and evaluation processes; and

- Identify implications from evaluation of the COAG trials for the ongoing implementation of the new arrangements.

- The new arrangements are based on administrative procedures, not legislative reform

A significant feature of the new arrangements is that they have been introduced solely through administrative mechanisms. The only aspect of the new arrangements that will be progressed through legislation at this point in time is the abolition of ATSIC.

Proceeding through administrative procedures provides the Government with great flexibility in how it implements the new arrangements. It also makes the new arrangements less transparent and more difficult to scrutinise. It has the potential, particularly over time, to make it more difficult for the Government to be held accountable for its performance. This is particularly so if monitoring and evaluation processes are not sufficiently rigorous. The issue of performance monitoring is discussed further below as one of the main challenges raised by the new arrangements.

- The introduction of the new arrangements do not depend on the abolition of ATSIC

As the Minister for Immigration, Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs has noted, 'the bulk of the Australian Government's reforms to Indigenous affairs are proceeding independently of (the ATSIC Amendment) Bill... The Bill does one thing. It abolishes ATSIC.'(57)

The simple fact is that all aspects of the new arrangements, other than the abolition of ATSIC and the transfer of some functions and assets from ATSIC to mainstream departments, have been achieved with ATSIC still in place. While addressing the goals of ensuring better whole of government coordination and improving accountability and accessibility of mainstream programs is long overdue, it is arguable that this too could have been achieved at any stage in the past without abolishing ATSIC.

ATSIC has been administratively de-funded and it is a reality that it will be abolished at some time in the coming months. The point to note here is that the implementation of the new arrangements does not depend on the passage of the ATSIC amendments.

The next section of this report discusses the challenge for the new arrangements of engaging with Indigenous communities and ensuring the participation of Indigenous peoples in decision making and program design. The new arrangements are built on a process of negotiating regional priorities with Indigenous representative bodies as well as negotiating shared responsibility agreements with local communities or groups. To date, there has been very little progress in advancing the creation of alternative regional representative Indigenous structures to ATSIC and it is difficult to see how such structures will come into existence by 1 July 2005. From regional consultations, it was also my strong impression that there has also been very little engagement of ATSIC Regional Councils since the new arrangements were introduced, due primarily to their upcoming demise.

While the challenges that this creates is discussed further below, I note that the existence of regional Indigenous representative structures over the next eighteen months will be vital to the success of the new arrangements. On this basis, continuation of ATSIC Regional Councils for at least a further twelve months than is currently envisaged may facilitate better frameworks for the implementation of the new arrangements. This possibility is discussed further in the section below. Other aspects of the new arrangements would remain unaffected by such a decision.

Practical matters relating to the introduction of the new arrangements

- There is a lack of information about the new arrangements in Indigenous communities. This contributes to an ongoing sense of uncertainty and upheaval

A practical issue that continually arose throughout my consultations (up to November 2004) for this report was the lack of information Indigenous people and communities had about the new arrangements. The further one moved away from Canberra, the less information and understanding was possessed by people about the new arrangements. In my view, this has caused great upheaval and uncertainty among Indigenous people and communities, and even among the bureaucracy tasked with implementing the changes.

Any change as wide-ranging as the new arrangements, and which is introduced so rapidly, will naturally cause significant upheaval and consternation. The challenge to government is to ensure that this upheaval is as minimal as possible and short term in its impact, and does not result in Indigenous people feeling further disempowered by government.

The Minister for Indigenous Affairs wrote to Indigenous organisations to explain the new arrangements soon after the Government's announcement in April 2004. This was before the practical details of how the arrangements would be implemented had been finalised. There has been no such communication since.