Native Title Report 2007: Chapter 10

Archived

You are in an archived section of the website. This information may not be current.

This page was first created in December, 2012

Chapter 10

Commercial fishing: A native title right?

- Defining native title

- Customary versus commercial

- Exclusive possession and commercial rights

- Indigenous economic development

- Policy and the Native Title Act

- Fishin Licenses

- And after the voyage

- Two case studies

The Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the Native Title Act) does not preclude the possibility that native title rights and interests recognised may be commercial rights and interests.

Yet throughout the legal and academic commentary on fishing rights available under native title, there have been two growing distinctions:

- That commercial rights and interests are not traditional rights and interests as required by the definition of native title in Section 223.

- That granting native title rights of a commercial nature would require the rights to be exclusive, and over sea country, exclusive native title rights have been held not to exist (High Court decision in Croker Island1).

There does not appear to be any convincing reason why these two distinctions are used to deny native title rights to fish commercially.

The current government’s pre-election policy supports an interpretation of Section 223 of the Native Title Act allowing a recognition of traditional native title rights and interests to fish commercially.

On 11 October 2001, the High Court determined that the Yarmirr people of Croker Island have a native title right to fish in their sea country.2 It was the first Australian decision to recognise Indigenous peoples’ right to native title over the sea. And it is now established law that native title rights and interests can include the right to fish or gather marine resources of the sea, rivers, lakes and inter-tidal zones.

In the Croker Island decision, the High Court held that native title rights and interests over marine waters relating to fishing and general access to the area are not exclusive. Being not exclusive means that the right of others who use and access the waters are unchanged (for example, the right of passage of vessels or the rights of commercial and public fishermen remain intact).3

While the Croker Island decision supports the existence of non-exclusive native title rights over sea country, the result did not necessarily exclude future native title applicants from establishing native title rights to fish commercially – two distinct concepts. To date however, the common law recognition of native title rights to sea country has predominantly concentrated on native title rights to fish and use marine resources for non-commercial purposes only.

But could the Native Title Act recognise a commercial right to fish as part of the interpretation of traditional rights and interests?

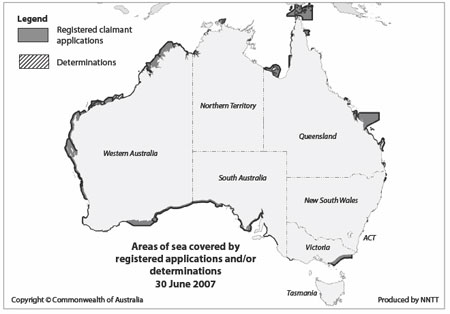

Current registered native title applications and determinations over sea country.

Defining native title

The preamble to the Native Title Act says that, where appropriate, governments have a responsibility to facilitate negotiation on proposals for the use of land (and waters) for economic purposes. Both the federal government and the opposition have promoted economic development as the foundation necessary to improve the lives of Indigenous Australians. In its 2007 Platform and Constitution, the Labor Government specifically acknowledged that native title is a valuable economic resource and that land and water provide the basis for Indigenous spirituality, law, culture, economy and wellbeing.4

Section 223 Native Title Act

In order for Indigenous people to have their native title rights and interests recognised, the key provision they must satisfy is the definition of ‘native title’ in Section 223 of the Native Title Act.

|

Section 223(2) of the Native Title Act expressly includes fishing rights as one of the rights and interests that may be protected by the recognition of native title. However, the section does not define the exact nature of such fishing rights except to the extent that they must have formed part of the traditional laws and customs.

In the High Court’s decision in Yorta Yorta5, the court expanded on the requirements of Section 223. The judgment set out three elements that constitute ‘traditional’ for the purposes of Section 233(1)(a). The laws and customs:

- must have been passed down from generation to generation;

- must have existed before the assertion of sovereignty. That is, the person must establish that the laws and customs considered are the normative rules of a society that existed before sovereignty; and

- must have had a continuous existence since sovereignty.

To have their native title rights and interests to fish recognised, Indigenous people must satisfy the requirements of Section 223, including those established in Yorta Yorta.

While some native title claimants have submitted that their native title rights include a right to fish commercially, the courts have rejected these claims on various grounds. Many of these grounds appear to stem from the somewhat common (but perhaps not always legitimately held) presumptions that:

- customary rights and commercial rights are two mutually exclusive concepts and therefore commercial rights are not considered to be traditional; and

- commercial rights are intrinsically connected to, and require, exclusive possession, which will not be granted under the Native Title Act (as seen in the Croker Island case).

Thus, we find:

- in theory, Indigenous Australians may have traditional rights and interests of commercial fishing on which they could capitalise;

- in practice, in the vast majority of cases Indigenous Australians have been unable to use the courts and the Native Title Act to access these rights and interests.

Customary versus commercial

Is there a valid distinction between customary and commercial practices?

The view that customary Indigenous laws and customs do not include commercial activity has created a false dichotomy that customary rights are mutually exclusive to commercial rights.6

There is growing evidence that this dichotomy is neither necessary nor accurate. For example, the story of the Gunditjmara people in Victoria provides evidence of an ancient aquaculture venture that was found to be the basis of a community grounded on economic exploitation (see the case study at the end of this chapter). This venture is now being revived with native title rights recognised by the Federal Court.

Significance of sea country

Sea country has played an integral role in Indigenous society for thousands of years. The Native Title Report 2000 identified the kinds of connections that are widely documented in relation to land, which are also present in relation to sea country. They include:

- many named places in the sea including archipelagos, rocks, reefs, sand banks, cays, patches of seagrass;

- named zones of the sea defined by water depth;7

- bodies of water associated with ancestral dreaming tracks;

- sacred sites that are the physical transformation of the dreaming ancestors themselves or a result of their activities;

- cloud formations associated with particular ancestors;

- sacred sites that can be dangerous because the power of the dreaming ancestors is still there (for example important places on reefs that can be used either to create storms or make them abate);

- ceremonial body painting and other painted designs using symbols of the sea (such as the tail of a whale, black rain clouds over white foaming waves, reefs, sandbanks, islands, foam on the sea, a reef shelf);

- particular kin groupings having a special relationship with tracks of the sea (by virtue of their inheritance of the sacred stories, songs, ceremonies and sacred objects associated with it and by exercising control over that area).

As identified by the claimants in the Croker Island case, the sea is a significant part of an ‘elaborate system of laws and customs that had been substantially maintained to the present day’. The claimants gave evidence that, when they talk about sea country, it is with the understanding that there is no essential difference between land and sea country.

The close connection is represented in the many stories of the physical and social world passed on by ancestors – stories that often start out at sea and move closer to land – stories creating seascapes of islands, reefs, sandbars – and travel on to create the landscapes.8 They are evidenced in song and storylines, ceremonies, dance, art works, coastal shell middens, and many sacred sites, places and artefacts along the coastline of Australia. They have also formed the basis for claims to country according to traditional law and custom.

Significance of fish and fishing

Fishing is an essential part of the connection with sea country. It provides the community with a source of food and nutrition, is important for ceremonial occasions, and is needed for barter and exchange.9 It provides Indigenous communities with an invaluable component of their cultural lifestyle and allows them to fulfil their traditional responsibilities related to kinship and land management.10 Through control of fisheries, Indigenous people can manage who can fish, where to fish, which fish, and how many fish can be taken at different times of the year.11

Fish and fishing are an important component of many cultural, ceremonial and social events. Cultural and social events involving fish can vary from entertaining visiting relatives to a cultural ban on eating red meat following a death in the family. During these times, the demand on fish and fishing becomes stronger. Some of what are viewed by Indigenous peoples as cultural events have evolved since pre-colonisation and are not restricted to traditional cultural events.

Sharing of fish is important socially and communally. Catches of fish are shared among the family, extended family and others who are not able to fish for themselves, such as the elderly. Sharing often extends to barter and exchange of fish for other items and other food sources within Aboriginal communities.12

Evidence of Indigenous trade

A significant amount of anthropological and archealogical research supports the existence and operation of trade between Australian Indigenous peoples and others. The trade was with other Indigenous peoples domestically and with Indigenous peoples internationally. This enterprise and economy has yet to be fully recognised by the native title system and the courts.

One reason for a continuing dichotomy between customary rights and commercial rights could be the difficulty that Indigenous people have faced in proving that they were involved in commercial fishing prior to colonisation.

In the Croker Island case, trial judge Justice Olney refused to grant recognition of the native title right to commercially fish due to insufficient evidence.13 With this finding (which was not supported on appeal) Justice Olney left open the possibility of claimants having these rights recognised when more compelling evidence of traditional customs of trade and barter is presented.

Similarly, in Neowarra v State of Western Australia14 the Federal Court held that the applicants did not possess a native title right to trade in the resources of their traditional land due to insufficient evidence.15 Justice Sundberg reasoned that on the balance of probabilities, it was difficult to certainly establish that there was a traditional trade in resources.16

Langton and others argue that:17

Aboriginal economic relations have been misconstrued as a type of primitive exchange … the profound alterity [otherness] of Aboriginal relationships among persons and things, as the Croker Island evidence of property and trade relations demonstrates, have been reconstituted in legal discourse as an absence of economic relations.

However, developments in anthropological and archaeological research and evidence support a change in approach, potentially allowing for a growth in evidence of commercial traditions in Indigenous Australia.

Indigenous trade routes

In inland Australia, Aboriginal people conducted widespread trade, of amongst other things, red ochre and a narcotic called pituri. The trade of these goods followed dreaming tracks that connected the waters of intermittent rivers …18

The trade routes linked coastal Australia with the inland, and Australia’s northern shores with the Indonesian archipelago and New Guinea. The items of trade were diverse … including pigments, narcotics, adornments, everyday utensils, even songs and stories. In some places, plentiful supplies of food allowed people to congregate at exchange centres to feast and trade. Some of the best known of these trading events were associated with the migrations of bogong moths in the Southern Alps of New South Wales, eels in Victoria, fish on the Darling River, and the ripening of bunya nuts in Queensland.

Despite popular belief, Australia was not an isolated continent. At the time of European colonisation there were trade links with Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. Macassan seafarers from the island of Sulawesi, in what is now Indonesia, made annual journeys to Australia’s northern shores to collect sea-slugs, also known as trepang or beche-de-mer. The trepang collected from Australia was in turn traded as far north as China, where they remain a culinary delicacy today. Aboriginal people exchanged trepang and turtle shell, out-rigger canoes, sails and tobacco, and even accompanied the traders to Macassar and back…

This trade ceased in the early twentieth century when Australia passed laws to protect the developing trepang industry in Australia. The influence of the Macassans on the spiritual and material life of northern Australian Aborigines is still evident today.

The weakening distinction between customary and commercial rights can also be seen in a recent native title consent determination between the Victorian Government and the Gunditjmara people (see the case study at the end of this chapter).

Exclusive possession and commercial rights

Australian courts have referred to a possible interpretation that the non-exclusive nature of native title rights and interests over the sea, consequently results in an inability to grant native title rights and interests of a commercial nature. Approaching exclusivity as a necessary pre-condition to the granting of commercial rights is another confusing approach to Indigenous peoples’ traditional rights and customs.

The Croker Island case was the first judgment to analyse the nature and extent of native title rights over sea country.19 In the first instance, Justice Olney found that although native title rights did exist within the determination area, as a matter of law they were not exclusive in nature.20 This was due to the fact that the native title rights were affected by, and considered to yield to, the right of innocent passage and the common law right of the public to fish and navigate.21 The right of the claimants to use their traditional lands operated only to the ‘extent of the inconsistency’22 and as such could not be utilised to prevent others from fishing or carrying out commercial activities in the area. In determining commercial native title rights and interests, Justice Olney held that there was not enough evidence to support this claim.23

The approach of Justice Olney to commercial native title rights was not followed by either the Full Federal Court or the High Court. The majority of the Full Federal Court held that the successful assertion of exclusivity was a necessary prerequisite to establishing a native title right to trade.24 Due to the fact that exclusive native title rights over sea country were held not to exist, the court did not consider the evidentiary merits of the claim to commercial fishing rights:25

… as a matter of experience in practical affairs, as well as for logical reasons, if it be accepted that the claimant community had no right to occupy these waters to the exclusion of all others, it is difficult to envisage how, in accordance with traditional custom, the group could assert, and effectively assert, a right to trade in the area’s resources.

While this appears to conflict with any potential finding of commercial native title fishing rights, commentators such as Lisa Strelein believe this is not so.26 Strelein argues that this determination should be narrowly construed as only applying to exclusive rights to trade in resources obtained from traditional land. Presumably, this does not affect the ability of Indigenous people to obtain a non-exclusive qualified right to trade27 – that is, the right of Indigenous people to trade in fish they catch, while simultaneously permitting the general public to fish in that area for either recreational or commercial purposes. Providing there is no policy intervention in the creation of such a system, it suffices to say that it is entirely within the realms of the Croker Island decision that this scheme could be established.

There is an interesting counterpoise in the Blue Mud Bay case, where exclusive rights were granted under Northern Territory law, where exclusive rights would not have been available under the Native Title Act. A study of this case is at the end of this chapter.

Indigenous economic development

Results of the survey conducted for the Native Title Report 2006, found that above all other roles, the majority of Indigenous people consider their roles as custodians and managers of their land and seas as more important than any other activity. This could be due to the fact that while Indigenous peoples were positive about enterprise development,28 the majority of survey respondents described a lack of capacity to develop potential economic opportunities.

They considered that while ‘economic development is an important tool in which to gain self determination and independence, it should not come at the expense of the collective identity and responsibilities to traditions, nor the decline in the health of country’.29

One traditional owner responded:

[We have no enterprise] as yet but have plans and need support to develop the ideas. We would like to develop fishing, aquaculture and tourism ventures. We need a management plan to include these ideas.30

In December 2007, the new Australian Government has identified economic development as a significant factor which ‘lies at the heart of efforts to improve the lives of Indigenous Australians’ and ‘supports Indigenous peoples using their lands for economic development’.31 This policy direction will play a significant role in Australia meeting the objectives of Article 1 of the Declaration on the Right to Development:32

Indigenous peoples (like every other person, and all peoples) are entitled to participate in, contribute to, and enjoy economic, social, cultural and political development.

Crucial to the successful implementation of the right to development for Indigenous people is the government’s obligation to ensure that its policies, legislations and practices make provision for the following:

- the right to self-determination;

- the right to protection of culture;

- economic, social and cultural rights;

- free, prior and informed consent; and

- equality.

As outlined in the preamble to the Native Title Act, native title should provide the foundation for Indigenous peoples’ economic development. The preamble provides that governments have an obligation ‘(where appropriate) to facilitate negotiation on Indigenous economic land use’.33 A grant of the native title right to fish for commercial purposes would allow traditional owner groups to use their land and waters for economic purposes and fulfil the objectives of the Native Title Act.

Enterprise development

Recognising the value of traditional knowledge and custom, many commentators have analysed the potential to create much needed economic opportunities for the Indigenous community. Instead of simply fishing for subsistence purposes, the Indigenous community could use their skills and knowledge to enter into the highly lucrative commercial fishing industry – in 2006 it was worth over $2.13 billion.34 This would not only provide communities with financial independence and employment opportunities, but would also significantly contribute towards allowing Indigenous people to control and manage country.35

Despite these benefits there is currently only a handful of Indigenous-owned commercial fishing businesses in operation throughout Australia, and only a small percentage of Indigenous employees within the industry itself.36 This distinct lack of active participation has been chiefly blamed on the licensing system currently operating in Australia, which requires each commercial fisher to obtain a license before they can sell the fish they catch. These licenses can only be obtained by purchasing them from either a stipulated Commonwealth or state authority or, in the event that all available licenses have been issued, from another commercial fishing company. Such licenses can command market prices in excess of $45,000;37 a sum many Indigenous fishermen simply cannot afford.

In recognition of the many economic and other barriers to Indigenous involvement in the fishing industry, in 2003, the then Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), called for an Indigenous Fishing Strategy which included a ten million dollar purchase of fishing licences and quotas across Australia. This was implemented through a partnership between ATSIC and Indigenous Business Australia (IBA) as the Indigenous Fishing Trust. The Trust is still in existence and is run through IBA’s self-funded investments.38

However some Indigenous people are making attempts to engage with the fishing industry including:

- the development of sponge farms at York and Goulburn Islands;

- farming mudcrabs in the Top End, Bynoe Harbour, south-west of Darwin, Darwin city and Maningrida;

- lobster fishing in Lockhart River, far north Queensland;

- trochus shell production north of Broome in the Kimberley; and

- farming eels in Victoria.

A number of government programs have been designed to assist with such enterprise development opportunities, including funding and support programs provided by:

- the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry;

- Indigenous Business Australia;

- the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations;

- the Department of Industry, Tourism and Resources;

- the Indigenous Land Corporation; and

- State and Territory departments and agencies.

These programs are integral to the successful development of Indigenous economic and entrepreneurial aspirations.

Management and conservation

Much of the activity on Indigenous land and waters has been land management and cultural heritage. Some state governments have made provision for joint management of national parks while others have not. Other traditional owners have negotiated agreements whereby they are able to meet their land management responsibilities (including cultural heritage) as community rangers. Often this work is voluntary or paid through the CDEP. Therefore, many of these Indigenous rangers are not paid at the same rate as if they were employed as Departmental rangers positions. There is grave concern as to the employment status of many Indigenous workers if CDEP is abolished.

Mining agreements, in particular, have provided opportunities for traditional owners to conduct cultural heritage site clearances – and be paid for their services.

More recently, Indigenous people have been engaged on management boards and committees concerned with land and waters. Some examples are;

- traditional owners from the Kimberley, Top End of the Northern Territory, southern Gulf of Carpentaria, Cape York and the Torres Strait, have joined forces with the North Australian Indigenous Land and Sea Management Alliance on the Dugong and Marine Turtle management project, to develop community-driven sustainable management of marine turtles and dugongs in northern Australia.

- The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) and traditional owner groups along the Great Barrier Reef are working together to establish cooperative arrangements for sea country management. Traditional Use of Marine Resource Agreements (TUMRAs) are being developed by traditional owner groups to describe formal management arrangements for a range of issues.

- The Australian Government Working on Country program builds on the history of land management. It contracts Indigenous people to provide environmental services in remote and regional areas. Also it is ideal for supporting traditional owner aspirations to conduct land management and conservation on their country. Their work will also help to maintain, restore, protect and manage Australia’s environment – the land, sea and heritage. This program will provide employment opportunities where traditional owners can be financially compensated for the work they do.

- The Northern Gulf Natural Resource Management Group manages the Carpentaria Ghost Nets Programme (CGNP), a program which involves removing ‘ghost’ fishing nets from the Gulf of Carpentaria and Torres Strait to stop the indiscriminate killing of marine life. While collecting the nets, the Sea Rangers also record information about the nets (only 5% of which originate in Australia) and treat and release any animals that are caught in the nets. The program works within five resource management regions including Cape York, Northern Gulf, Southern Gulf, Torres Strait and the Northern Territory.39

- Indigenous tourism permits aim to achieve cooperative management arrangements between government, traditional owner groups and industry.

Policy and the Native Title Act

The immense difficulty Indigenous people face in having their traditional commercial fishing rights recognised under the Native Title Act may prove to be another example of how Indigenous peoples’ ability to use native title rights and interests for economic development is frustrated by the very nature of the rights recognised, and the legal framework of native title.

… while customary fishing rights speak to rights of cultural self-determination and the preservation of a distinctive identity, commercial fishing rights are an important part of the right to economic determination. The co-existence and cross-fertilisation of these two sets of rights is currently recognised and implemented in practice in New Zealand, Canada and the United States – the three countries in which Indigenous peoples have a legal position close to that of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in Australia …

Australia currently stands outside these international developments given that the overwhelming emphasis is on customary rights as opposed to commercial fishing rights …

The bulk of academic commentary also supports the assumption that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be confined to exercising rights of customary use and small scale subsistence fishing only.40

Tony McAvoy argues that native title is the tool whereby economic use and benefit of resources may be achieved.41 The current Indigenous economic policy direction could be furthered by enabling Indigenous people to access and use their traditional commercial fishing rights through the Native Title Act.

Fishing licenses

Section 211 of the Native Title Act provides for the interaction of:

- native title rights and interests that include recognising a right to undertake certain activities (such as fishing or hunting); and

- Commonwealth, state or territory government regulation of that activity (such as licensing).

If a government regulates an activity under the section, then that regulation does not apply to restrict native title rights and interests to the extent that the activities are undertaken for personal, domestic or non-commercial needs. The necessary conclusion from this is that government regulation applies if the fishing is to be undertaken for commercial reasons.

Under the Native Title Act, native title holders can exercise their rights to fish for personal, domestic or non-commercial needs without obtaining a permit or licence.42

The interaction will always be complex and will differ from case to case. As an aside, in the majority in the Croker Island case43 the court said that, in ascertaining the existence of the right to trade, it will need to specifically look at how this common law recognition will be impacted on by the relevant legislation enacted in the jurisdiction in which the traditional lands are located:44

… any final consideration of a claim of a right to fish, hunt and gather within these waters for the purposes of trade, would need to take into account the impact of relevant respective fishing legislative regimes of South Australia, the Territory and the Commonwealth …

It will suffice for us to say that, by this means, any right of the public to fish for commercial purposes, and any such traditional right, were at least regulated and possibly wholly or partially extinguished by statute or executive act or both.

As a result, even if Indigenous people can overcome all of the Section 223 requirements – and prove that their tradition, rights, and customs include commercial fishing – these rights can be significantly curtailed by government regulation.

And after the voyage

Commercial fishing rights are essential to Indigenous people of Australia. Not only are they traditional rights but they are also integral to the economic development of Indigenous communities.

The importance of fishing and the use of all land and sea resources are recognised in the Native Title Act by both the preamble and Section 223(2) which expressly includes fishing rights as one of the rights and interests which may be protected by the recognition of native title.

Yet the courts have rejected many claims for native title rights to fish commercially. When examining these cases, there appears to be a somewhat common, but perhaps ungrounded distinction between customary rights and commercial rights.

On the other hand, the cases also appear to point to commercial rights being intrinsically connected to, and in fact requiring, exclusive possession in order to be granted as a native title right or interest.

Indigenous Australians may theoretically have native title rights and interests of commercial fishing on which they could capitalise, however, in the vast majority of cases the courts have rejected this in practice.

Nevertheless there is a growing desire for Indigenous economic policy to enable Indigenous people to gain access and use of their traditional commercial fishing rights through the Native Title Act.

Two case studies

The Gunditjmara: World’s oldest aquaculture venture? |

|

In March 2007, Justice North handed down the Federal Court’s native title consent determination in Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria.45 The case determined that native title rights and interests did exist in the claim area. The area being primarily sea and some land:46 … bounded on the west by the Glenelg River, to the north by the Wannon River and extends as far east as the Shaw River. It includes Lady Julia Percy Island and coastal foreshore between the South Australian border and the township of Yambuk. The application for native title determination relates to Crown land and waters within the application area including state forests, national parks, recreational reserves, river frontages and coastal foreshores comprising 140,000 hectares. An eight-year research study revealed that for nearly 8,000 years the Gunditjmara people commercially farmed eels.47 In what is considered to be Australia’s earliest and largest aquaculture venture, this settled Aboriginal community systematically farmed eels as both a source of food and for barter and trade. The Gunditjmara modified more than 100 square kilometres of the landscape. They built stone dams to hold the water in the areas, created ponds and wetlands in which they grew short-fin eels and other fish, and constructed channels to interconnect the wetlands.48 The community then traded their product to others, becoming an important part of the local economy of Indigenous clans.49 The native title determination recognises that the Gunditjmara People have non-exclusive native title rights over 133,000 hectares of land and sea:

However, the determination provides that:

The determination set out the extent and nature of other interests, including those of the interests of people holding licences, permits, statutory fishing rights, or other statutory rights pursuant to state and Commonwealth legislation.50 |

|

After originally not agreeing to a mediated consent determination, mediation was given further impetus by an early evidence hearing at the conclusion of which Justice North expressed surprise at the lack of progress in negotiation given the strength of the evidence. This evidence included the Commonwealth of Australia Gazette of 20 July 2004 which listed the area in the Register of the National Estate:

Eventually an agreement was made and the Federal Court endorsed it. Justice North, in ordering the determination, referred to the significance of the area to the Gunditjmara people as:51

Justice North made the Federal Court’s order on the determination saying (in paragraphs 5, 8 and 9) that the native title rights and interests of the Gunditjmara people consists of:

|

|

The other interests listed in Schedule 4, that will continue to exist, includes any public right to fish, and ‘the interests of persons holding licences, permits, statutory fishing rights, or other statutory rights’ under Victorian or Commonwealth legislation.52 The determination therefore explicitly provides the Gunditjmara people with a right to take resources from the sea. Nowhere in the determination are they limited by their use of these resources and the extent to which these resources may be taken except to the extent that these conflict with state or Commonwealth law. The Gunditjmara people have already started to use these rights to re-establish eel farming and smoking in the area inline with their tradition, including by reversing the drainage system installed by Europeans. The Gunditjmara people are considering using the eel to create a brand for Budj Bim smoked eel.53 |

Blue Mud Bay: Exclusivity and fishing rights |

|

In the Blue Mud Bay case,54the court held that the Indigenous claimants have exclusive access rights to inter-tidal zones granted under the Commonwealth Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (ALRA).55 Blue Mud Bay is a small inlet located in north-east Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. In a previous claim, the Commonwealth had granted this bay to the Yolgnu people56 as part of the Arnhem Land Trust under the ALRA. In June 2002, the Yirritja moiety clans57 and the Dhuwa moiety clans58 (of the Yolgnu people) lodged a claim seeking clarification of the rights provided under the ALRA, and a determination of their native title rights and interests over the area. One aspect was whether or not the clans of the two moieties possessed the right to exclude others from entering onto, taking resources from or using the foreshore area (more commonly called the inter-tidal zone). Specifically, the claimants sought a declaration of the operation of the Northern Territory Fisheries Act 1998 which allows the Director of Fisheries to issue commercial fishing licenses for fishing in the area. |

|

Initially, Justice Selway ruled in accordance with the Croker Island decision, holding that the fee simple estate in the tidal foreshore did not authorise the land trust to exclude those exercising common law public rights to fish or navigate in the inter-tidal zone and/or that people exercising public rights to fish or navigate can come onto the inter-tidal zone without breaching the ALRA.59 All native title rights recognised by the common law were to be held subject to the other rights and interests operating in that region.60 This decision was appealed by the claimants to the Full Federal Court. They sought a declaration that grants made pursuant to the ALRA conferred exclusive possession on the title holders and allowed them to exclude others from fishing in the inter-tidal zones. In reaching a conclusion on this issue the Full Court considered it necessary to ‘independently consider the correctness of Commonwealth v Yarmirr.’61 The judgment criticised the majority decision in Yarmirr for not looking at the ALRA when determining the nature of inter-tidal zone rights attached to land granted under the ALRA.62 The court said:63

The court found that under Section 73(1)(d) of the ALRA, the legislative power of the Northern Territory extends to prohibiting entry into, and controlling fishing and other activities in

Thus, in order to ascertain whether the clans of the Yirritja moiety and the clans of the Dhuwa moiety possessed exclusive title, it was necessary to identify whether the foreshore (inter-tidal zone) fell within the scope of the definition of the ‘water of the sea’.65 In characterising the inter-tidal zone, the courts followed the majority reasoning in the Full Court judgment of Risk.66 In that case, the issue was whether the seabed of bays and gulfs beyond the low water mark could be the subject of a claim under the ALRA; that is, whether it was classified as ‘land in the Northern Territory’.67 The majority judgment in Risk concluded that it was not. The Full Court in Gumana reiterated this finding by stating:68

The consequence was that the Fisheries Act had no application to areas within the boundary lines of the ALRA grant. As a result, the Northern Territory Director of Fisheries had no power to grant a licence in areas subject to the grant. The licenses that had been granted over the ALRA grant areas were invalid and this included the water that flowed over the land subject to those grants.69 The decision is being appealed to the High Court and the decision is expected to be handed down in early 2008. If upheld, Indigenous people will hold exclusive possession rights to the inter-tidal zone of over 80% of the Northern Territoy coastline. |

Footnotes

[1] Commonwealth v Yarmirr (2001) 208 CLR 1.

[2] Commonwealth v Yarmirr (2001) 208 CLR 1.

[3] See National Native Title Tribunal, Fishing and Native Title: What rights apply?, Native Title Facts, National Native Title Tribunal, available online at: http://www.nntt.gov.au/publications/1021874397_11824.html.

[4] Australian Labor Party, ALP National Platform and Constitution 2007, available online at: http://www.alp.org.au/platform/index.php.

[5] Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria & others (2002) 194 ALR 538.

[6] See Tsamenyi, M., and Mfodwo, K., Towards Greater Indigenous Participation in Australian Commercial Fisheries: Some Policy Issues, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission National Policy Office Policy Paper Series, Australian and Torres Strait Islander Commission, 2000, p13.

[7] Chase, A., and Sutton, P., ‘Hunter-Gatherers in a Rich Environment: Aboriginal Coastal Exploitation in Cape York Peninsula’ in Keats, A., (ed) Ecological Biogeography in Australia, W. Junk, London, 1981, cited in Myers, G., O’Dell, M., Wright, G., and Muller S., A Sea Change in Land Rights Law: The Extension of Native Title to Australia’s Offshore Areas, Native Title Research Unit, Legal Research Monograph, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra, 1996, p11.

[8] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Native Title Report 2000, Sydney 2000, p86.

[9] Coleman, P.M., Henry, G.W., Reid, D.D., and Murphy J.J., Indigenous Fishing Survey of Northern Australia, FRDC Project No. 99/158, National Recreational and Indigenous Fishing Survey.

[10] Coleman, P.M., Henry, G.W., Reid, D.D., and Murphy J.J., Indigenous Fishing Survey of Northern Australia, FRDC Project No. 99/158, National Recreational and Indigenous Fishing Survey.

[11] Dunn, B., Angling in Australia: Its history and writings, 1st edn., David Ell Press, Australia, 1991, p45.

[12] Government of Western Australia, Department of Fisheries, Customary Fishing, available online at: http://www.fish.wa.gov.au/docs/pub/IndigenousFisheries/index.php?0007, accessed 25 October 2007.

[13] Yarmirr v Northern Territory of Australia (No 2) (1998) 156 ALR 370, per Olney J, para [130].

[14] Neowarra v State of Western Australia [2003] FCA 1402.

[15] Neowarra v State of Western Australia [2003] FCA 1402, per Sundberg J, para [481].

[16] Neowarra v State of Western Australia [2003] FCA 1402, per Sundberg J, para [481].

[17] Langton, M., Mazel, O., Palmer, L., ‘The Spirit of the Thing: The Boundaries of Aboriginal Economic Relations at Common Law’, The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 2006, 17:3, 307 – 321, p1.

[18] Macleay Museum News, Shaping Australia, pp1-2, available online at: http://www.usyd.edu.au/su/macleay/cnews18.htm#18top, accessed 25 October 2007. There are various other reports of trade internationally and domestically. See for example, Sustainable Development for Traditional Inhabitants of the Torres Strait Region, David Lawrence, Coordinator, Torres Strait Baseline Study, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, pp482-483, available online at: http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/4173/ws016_paper_4…, accessed 25 October 2007 and National Oceans Office, Sea Country, and Indigenous Perspective The South-east Regional Marine Plan Assessment Reports, 2002, p6, available online at: http://eied.deh.gov.au/coasts/mbp/publications/pubs/indigenous-perspect…, accessed 26 October 2007.

[19] Yarmirr v Northern Territory of Australia (No 2) (1998) 156 ALR 370.

[20] Yarmirr v Northern Territory of Australia (No 2) (1998) 156 ALR 370, per Olney J, para [423].

[21] Yarmirr v Northern Territory of Australia (No 2) (1998) 156 ALR 370, per Olney J, para [431].

[22] Yarmirr v Northern Territory of Australia (No 2) (1998) 156 ALR 370, per Olney J, para [389].

[23] Yarmirr v Northern Territory of Australia (No 2) (1998) 156 ALR 370, per Olney J, para [130].

[24] Commonwealth v Yarmirr (1999) 168 ALR 426, per Beaumont and von Doussa JJ, para [480].

[25] Commonwealth v Yarmirr (1999) 168 ALR 426, per Beaumont and von Doussa JJ, para [480].

[26] Strelein, L., ‘A comfortable existence: commercial fishing and the concept of tradition in Native Title’ (2002), 5, Balayi culture, law and colonialism, 94, p96.

[27] Strelein, L., ‘A comfortable existence: commercial fishing and the concept of tradition in Native Title’ (2002), 5, Balayi culture, law and colonialism, 94, p96.

[28] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Native Title Report 2006, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Sydney, 2006, p23.

[29] Traditional owner from the Yorta Yorta Nation Aboriginal Corporation, Survey Comment, HREOC National Survey on Land, Sea and Economic Development 2006.

[30] Traditional owner of the Umpila territories, Cape York, Survey Comment, HREOC National Survey on Land, Sea and Economic Development 2006.

[31] Australian Labor Party, New Leadership – Indigenous Economic Development, available online at http://alp.net.au/download/now/indig_econ_dev_statement.pdf, accessed December 2007.

[32] Declaration on the Right to Development, Article 1.

[33] Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), preamble.

[34] (ABARE) 2007, Australian Fisheries Statistics 2006, Australian Bureau of Agriculture and Resource Economics, Canberra.

[35] See generally, Australian Law Reform Commission, The Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Laws, Report No 31 (1986). See also O’Reagan, T., Access to Fisheries: The Maori experience, Speech delivered at Indigenous Fishing Conference: Moving Forward 2003, Freemantle, 28 October 2003, for an example of the autonomy that commercial fishing rights has given New Zealand Moaris.

[36] Altman, J.C., Arthur W.S., and Bek H.J., Indigenous participation in commercial fisheries in Torres Strait: A preliminary discussion, Discussion Paper 73/1994, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, p1.

[37] Summerfield, P,. Management Implications of the Native Title Act: A Western Australian Perspective, Paper presented at the Australasian Fisheries Managers Conference, Wellington, 1-4 August 1994, p6.

[38] Wanganeen, K., Indigenous participation in the Australian commercial fishing industry, Presentation given at the Indigenous Fishing Conference: Moving Forward 2003, Freemantle, 28 October 2003, available online at: http://www.nntt.gov.au/metacard/files/Fishing_conference/Fishing_confer…. See also Indigenous Business Australia website, available online at: http://www.iba.gov.au/ibainvestments/agriculture,forestryandfishing/

[39] Gunn, R., ‘Carpentaria Ghost Net Program – Saltwater People Working Together’ (2007), 13(2), Waves, p11, available online at: http://www.mccn.org.au/content/1729/Waves%2013(2)%20low%20res.pdf.

[40] See Tsamenyi, M., and Mfodwo, K., Towards Greater Indigenous Participation in Australian Commercial Fisheries: Some Policy Issues, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission National Policy Office Policy Paper Series, Australian and Torres Strait Islander Commission, 2000, p13.

[41] McAvoy T., Indigenous fisheries: cultural, social and commercial, paper presented at The Past and Future of Land Rights and Native Title Conference, Townsville, 28-30 August 2001.

[42] National Native Title Tribunal, Fishing and Native Title: What rights apply?, Native Title Facts, National Native Title Tribunal, available online at: http://www.nntt.gov.au/publications/1021874397_11824.html.

[43] Commonwealth v Yarmirr (1999) 168 ALR 426.

[44] Commonwealth v Yarmirr (1999) 168 ALR 426, per Beaumont and von Doussa JJ, para [481].

[45] Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria [2007] FCA 474. The respondents to the claim were 170 individual parties including the State and Commonwealth Government and mining, farming, fishing and other land user interests. The determination was made after the parties reached an agreement, Section 87 of the Native Title Act allows the court to make a determination consistent with that agreement without a hearing.

[46] Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria [2007] FCA 474, per North J, para [3]. The determination was only over part of the claim area – Part A – Part B is an area of land on the eastern edge of the application area and Part A is the balance.

[47] Builth, H., Identifying A Site Signature of Gunditjmara Settlement in Southwest Victoria, Paper presented at Barriers, Borders, Boundaries Australian Archaeological Association Annual Conference, Hervey Bay, Queensland, 2001.

[48] Builth, H., Identifying A Site Signature of Gunditjmara Settlement in Southwest Victoria, Paper presented at Barriers, Borders, Boundaries Australian Archaeological Association Annual Conference, Hervey Bay, Queensland, 2001.

[49] Builth, H., Identifying A Site Signature of Gunditjmara Settlement in Southwest Victoria, Paper presented at Barriers, Borders, Boundaries Australian Archaeological Association Annual Conference, Hervey Bay, Queensland, 2001.

[50] Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria [2007] FCA 474, schedule 2.

[51] Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria [2007] FCA 474, per North J, para [4].

[52] Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria [2007] FCA 474, schedule 4.

[53] Mosig, J., ‘Gunditjmara to resurrect an ancient aquaculture’, Koori Mail, 21 November 2007, p33.

[54] Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia (2005) 218 ALR 292. The case is currently being heard on appeal by the High Court. The High Court’s decision is expected to be handed down early in 2008.

[55] Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia (2005) 218 ALR 292.

[56] The Yolngu people are the traditional owners of parts of north-east Arnhem land, including areas of Blue Mud Bay.

[57] The eight Yirritja Moiety clans claiming native title were (1) Yarrwidi Gumatj, (2) Manggalili, (3) Gumana Dhalwangu, (4) Wunungmurra (Gurrumuru) Dhalwangu, (5) Dhupuditj Dhalwangu, (6) Munyuku, (7) Yithuwa Madarrpa, (8) Manatja.

[58] The seven Dhuwa Moiety clans claiming native title were (1) Gupa Djapu, (2) Dhudi Djapu, (3) Marrakulu 1, (4) Marrakulu 2, (5) Djarrwark 1, (6) Djarrwark 2, (7) Galpu.

[59] Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia (2005) 218 ALR 292.

[60] Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia (2005) 218 ALR 292, para [331].

[61] Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia (2005) 218 ALR 292. Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia [2007] 158 FCR 349, para [92].

[62] Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia (2005) 218 ALR 292, para [92].

[63] Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia (2005) 218 ALR 292, para [92].

[64] Aboriginal Land Rights Act (Northern Territory) 1976 (Cth), s73.

[65] Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia [2007] 158 FCR 349, para [92].

[66] Risk v Northern Territory (2002) 210 CLR 392.

[67] Webb, R., ‘Is the Inter-tidal zone ‘land’ or is it ‘sea’- and some native title issues’ (2007), 1, Northern Territory Law Journal, 33, p47.

[68] Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia [2007] 158 FCR 349, para [90].

[69] Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia [2007] 158 FCR 349, para [105].