Federal Discrimination Law: Chapter 6 - Practice and Procedure

Chapter 6 Practice and Procedure

Back to index

![]() Download Chapter 6 in PDF [555 KB]

Download Chapter 6 in PDF [555 KB]

![]() Download Chapter 6 in Word [556 KB]

Download Chapter 6 in Word [556 KB]

- 6.1 Introduction

- 6.2 Parties to a complaint to HREOC

- 6.3 Interim Injunctions

- 6.4 Election of Jurisdiction

- 6.5 HREOC Act is an Exclusive Regime

- 6.6 Scope of Applications Made Under s 46PO of the HREOC Act to the FMC and Federal Court

- 6.7 Relevance of Other Complaints to HREOC

- 6.8 Pleading Direct and Indirect Discrimination as Alternatives

- 6.9 Applications for Extension of Time

- 6.10 State Statutes of Limitation

- 6.11 Interim Injunctions Under s 46PO(6) of the HREOC Act

- 6.12 Applications for Summary Disposal

- 6.12.1 Changes to rules concerning summary disposal of proceedings

- 6.12.2 Principles governing determination of whether there are ‘no reasonable prospects’

- 6.12.3 Onus/material to be considered by the Court

- 6.12.4 Examples of matters where the power has been exercised

- 6.12.5 Frivolous or vexatious proceedings and abuse of process

- 6.12.6 Dismissal of application due to non-appearance of applicant

- 6.13 Application for Dismissal for Want of Prosecution

- 6.14 Application for Suppression Order

- 6.15 Interaction Between the FMC and the Federal Court

- 6.16 Appeals from the FMC to the Federal Court

- 6.17 Approach to Statutory Construction of Unlawful Discrimination Laws

- 6.18 Standard of Proof in Discrimination Matters

- 6.19 Miscellaneous Procedural and Evidentiary Matters

- 6.19.1 Request for copy of transcript

- 6.19.2 Unrepresented litigants

- 6.19.3 Representation by unqualified person

- 6.19.4 Consideration of fresh evidence out of time

- 6.19.5 Statements made at HREOC conciliation

- 6.19.6 Security for costs

- 6.19.7 Applicability of s 347 of the Legal Profession Act 2004 (NSW) to federal discrimination cases

- 6.19.8 Judicial immunity from suit under federal discrimination law

- 6.19.9 Adjournment pending decision of Legal Aid Commission

- 6.19.10 Appointment of litigation guardians under the FMC Rules

- 6.19.11 ‘No case’ submission

6.1 Introduction

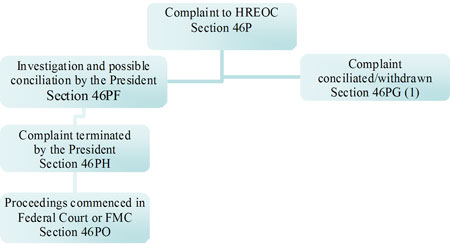

The procedure for making complaints of federal unlawful discrimination is set out in Part IIB of the HREOC Act.[1] That procedure can be summarised as follows.

- A person may make a written complaint to HREOC alleging unlawful discrimination under the RDA, SDA, DDA or ADA.[2] The President of HREOC inquires into and attempts to conciliate such complaints.[3]

- The President has powers to obtain information relevant to an inquiry[4] and can direct the parties to attend a compulsory conference.[5]

- The President may terminate a complaint on the grounds set out in s 46PH, being:

(a) the President is satisfied that the alleged unlawful discrimination is not unlawful discrimination;

(b) the complaint was lodged more than 12 months after the alleged unlawful discrimination took place;

(c) the President is satisfied that the complaint was trivial, vexatious, misconceived or lacking in substance;

(d) in a case where some other remedy has been sought in relation to the subject matter of the complaint—the President is satisfied that the subject matter of the complaint has been adequately dealt with;

(e) the President is satisfied that some other more appropriate remedy in relation to the subject matter of the complaint is reasonably available to each affected person;

(f) in a case where the subject matter of the complaint has already been dealt with by the Commission or by another statutory authority—the President is satisfied that the subject matter of the complaint has been adequately dealt with;

(g) the President is satisfied that the subject matter of the complaint

could be more effectively or conveniently dealt with by another statutory authority;(h) the President is satisfied that the subject matter of the complaint involves an issue of public importance that should be considered by the Federal Court or the Federal Magistrates Court; or

(i) the President is satisfied that there is no reasonable prospect of the matter being settled by conciliation.[6]

- Once a notice of termination has been issued by the President, an ‘affected person in relation to the complaint’ may make an application to the Federal Court or the Federal Magistrates Court (‘FMC’) alleging unlawful discrimination by one or more respondents to the terminated complaint.[7] The application may be made regardless of the ground upon which a person’s complaint is terminated by the President.

- An application must be filed within 28 days of the date of issue of the termination notice,[8] although the court may allow further time (discussed at 6.9 below).

The Federal Court Rules (Cth) (‘Federal Court Rules’) and Federal Magistrates Court Rules 2001 (Cth) (‘FMC Rules’) impose additional procedural requirements in relation to the commencement of applications in unlawful discrimination matters.[9]

Figure 1: Overview of Federal Unlawful Discrimination Law Procedure

6.1.1 Role of the special purpose commissioners as amicus curiae

The Race Discrimination Commissioner, Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Disability Discrimination Commissioner, Human Rights Commissioner and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner are given an amicus curiae function in relation to proceedings arising out of a complaint before the Federal Court or the FMC.[10]

In Access For All Alliance (Hervey Bay) Inc v Hervey Bay City Council,[11] Collier J considered the principles to be applied in determining an application by a special purpose Commissioner for leave to appear as amicus curiae. Her Honour noted the following view of Brennan CJ in Levy v State of Victoria as to the general basis upon which an amicus curiae is heard:[12]

The footing on which an amicus curiae is heard is that that person is willing to offer the Court a submission on law or relevant facts which will assist the Court in a way in which the Court would not otherwise have been assisted.[13]

Her Honour then referred to the particular position of the special purpose Commissioners by reason of their statutory amicus curiae function under the HREOC Act. Her Honour stated:

The amicus curiae function conferred on the special purpose Commissioners under the HREOC Act, in my view indicates acknowledgement by Parliament that the Court can obtain useful assistance from the Commissioners as statutory amicus curiae. In the HREOC Act, Parliament also recognises the position, expertise and knowledge of the Commissioners, and I note the duties and functions of the Commission as set out in s 10A and s 11 of the HREOC Act to that effect.[14]

This chapter now considers particular procedural and evidentiary issues that have arisen in federal unlawful discrimination matters. The structure of the chapter mirrors the chronological stages of proceedings, from the initial complaint to HREOC through to the Federal Court and FMC. As noted in Chapter 1, not all relevant aspects of procedure and evidence relevant to federal unlawful discrimination matters are discussed: only those aspects that have been considered in cases decided in the jurisdiction.

6.2 Parties to a complaint to HREOC

6.2.1 Complainants

Under s 46P of the HREOC Act a complaint may be lodged with HREOC alleging unlawful discrimination by:

- a person aggrieved by the unlawful discrimination, on that person’s own behalf, or on behalf of that person and one or more other persons who are aggrieved by the alleged unlawful discrimination;[15]

- by two or more persons aggrieved by the alleged unlawful discrimination, on their own behalf, or on behalf of themselves and one or more other persons who are also aggrieved by the alleged unlawful discrimination;[16] or

- by a person or trade union on behalf of one or more other persons aggrieved by the alleged unlawful discrimination. [17]

In all cases there must be ‘a person aggrieved’ before a complaint can be lodged with HREOC. The HREOC Act does not define ‘a person aggrieved’.[18]

The meaning of ‘person aggrieved’ was considered in Access For All Alliance (Hervey Bay) Inc v Hervey Bay City Council[19] (‘Hervey Bay’). In this case the applicant was a volunteer incorporated association that was established to advance equitable and dignified access to premises and facilities. It alleged that the respondent council was in breach of s 32 of the DDA by maintaining bus stops that failed to comply with the relevant disability standard.[20] Collier J summarily dismissed the application, finding that the applicant was not a ‘person aggrieved’.

Collier J outlined the following guiding principles in determining whether an organisation is a ‘person aggrieved’:

(a) the question is a mixed question of law and fact;[21]

(b) the complainant must show that they have a grievance that is beyond that which will be suffered by an ordinary member of the public to satisfy the test;[22]

(c) the test is an objective, not a subjective one, so the mere fact that a person feels aggrieved or has no more than an intellectual or emotional concern is not sufficient;[23]

(d) the phrase includes a person who has a genuine grievance because the action prejudicially affects their interests;[24]

(e) there is a different jurisprudential basis for identifying whether an applicant has a ‘special interest’ in the subject of proceedings sufficient to be granted standing under general law, compared with whether an applicant is a person aggrieved for the purposes of a statutory right of action such as under the HREOC Act, although in resolving these questions, the matters taken into account are often similar;[25] and

(f) ‘person aggrieved’ should not be interpreted narrowly and should be given a construction that promotes the purpose of the relevant Act.[26]

Her Honour also identified a number of principles relating to the circumstances in which bodies corporate can be a ‘person aggrieved’ for the purpose of the HREOC Act: see below.

Collier J noted the view expressed by Ellicott J in Tooheys Ltd v Minister for Business & Consumer Affairs[27] that in most cases it would be more appropriate to deal with the question of whether an applicant is a ‘person aggrieved’ at a final hearing when all of the facts are before the court and the court has the benefit of full argument on the matter. In spite of this, in Hervey Bay, her Honour considered it appropriate to deal with this issue at an early stage because the parties had had an opportunity to file evidence in relation to the issue and the applicant was not disputing the appropriateness of her determining the issue at that stage of the proceedings.

Her Honour found that Access For All Alliance (Hervey Bay) Inc was not a ‘person aggrieved’ as its interest in the proceedings was no greater than the interest of an ordinary member of the public. Justice Collier said:

Notwithstanding its intellectual and emotional concern in the subject matter of the proceedings, the interest of the applicant is no more than that of an ordinary member of the public; the applicant is not affected to an extent greater than an ordinary member of the public, nor would the applicant gain an advantage if successful nor suffer a disadvantage if unsuccessful.[28]

Justice Collier, in reaching her decision, adopted the reasoning of the Full Court of the Federal Court in Cameron v Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission[29] (‘Cameron’) and the reasoning of Wilcox J in the Executive Council of Australian Jewry v Scully[30] (‘Scully’).[31]

The applicant in Cameron had made a complaint to HREOC alleging that a scholarship scheme run by the Australian International Development Assistance Bureau for Fijian students constituted racial discrimination in breach of the RDA. HREOC declined the applicant’s complaint on the basis that the complainant was not an ‘aggrieved person’.

The applicant sought judicial review of HREOC’s decision. In the Federal Court he contended that he was a ‘person aggrieved’ because:

- he was a legal practitioner who had acted for persons in proceedings concerning racial discrimination and civil rights in Fiji;

- he had received a scholarship as a student and was aware of the privileges and duties associated with such an award;

- he had continuing professional and personal links with Fiji; and

- he had a personal sense of moral duty about matters concerning Fiji and its citizens.[32]

At first instance,[33] Davies J dismissed the application saying that the applicant was not an ‘aggrieved person’. His finding was upheld on appeal.[34]

Beaumont and Foster JJ held that the question of whether a person is a ‘person aggrieved’ is a mixed question of law and fact to be determined objectively, and that the mere feeling of being aggrieved will not be sufficient.[35]

In a separate judgment, French J, while also dismissing the appeal, stated that the categories of interest to support locus standi should not be considered as being closed:

It is at least arguable that derivative or relational interests will support the claim of a person to be ‘aggrieved’ for the purposes of the section. A close connection between two people which has personal or economic dimensions, or a mix of both, may suffice. The spouse or other relative of a victim of discrimination or a dependent of such a person may be a person aggrieved for the purposes of the section. It is conceivable that circumstances could arise in which a person in a close professional relationship with another might find that relationship affected by discriminatory conduct and have the necessary standing to lay a complaint.

The categories of eligible interest to support locus standi under this statutory formula or for the purposes of prerogative relief are not closed. This much was demonstrated in Onus v Alcoa of Australia Ltd (1981) 149 CLR 27. There the qualifying interest was described as ‘a cultural and historical interest ...’ (at 62). While it will often be the case that such interests or relational interests of the kind referred to above may overlap with intellectual or emotional concerns, the presence of the latter does not defeat the claim to standing. [Therefore] I do not exclude the possibility that a case might arise in which a personal affiliation with a particular individual or group who claims to be the victim of discrimination might support standing to lay a complaint under the [RDA].[36]

In Scully,[37] Wilcox J held that the Executive Vice President of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, Mr Jones, was a ‘person aggrieved’. The complaint related to material distributed to members of the public in Launceston which was alleged to constitute racial hatred in breach s 18C of the RDA. Wilcox J found that the Executive Vice President was a ‘person aggrieved’, despite the fact that Mr Jones lived in Sydney, not Launceston. Wilcox J noted that

Mr Jones’ claim of special affection did not depend on his place of residence. He offered himself as complainant because he was the Executive Vice President of a body that represented 85% of the Jewish population of Australia. He was a senior officer of the Council with major responsibility for the achievement of its objects. They included representing Australian Jewry, including Jews resident in the Launceston district. To describe Mr Jones’ connection with the matter simply as ‘a Jewish Australian living in Sydney’ was to ignore his representative role.[38]

His Honour concluded that Mr Jones had a ‘special responsibility to safeguard the interests of a group’ and was therefore a ‘person aggrieved’.[39]

The aforementioned cases suggest that whilst a complainant does not necessarily have to be the victim of discrimination to be a ‘person aggrieved’, the complainant must show that they have a genuine grievance that goes beyond that of an ordinary member of the public in order to be found to be an ‘aggrieved person’.[40]

(i) Can a body corporate be a ‘person aggrieved’?

In Koowarta v Bjelke-Petersen[41] (‘Koowarta’), Mason J held that ‘a person aggrieved’ included a reference to a body corporate:

By virtue of s 22(a) of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) a reference in a statute to a person includes a reference to a body corporate, unless a contrary intention appears. It is submitted that because, generally speaking, human rights are accorded to individuals, not to corporations, ‘person’ should be confined to individuals. But, the object of the Convention being to eliminate all forms of racial discrimination and the purpose of s 12 [of the RDA] being to prohibit acts involving racial discrimination, there is a strong reason for giving the word its statutory sense so that the section applies to discrimination against a corporation by reason of the race, colour, or national or ethnic origin of any associate of that corporation.[42]

Applying Koowarta in Woomera Aboriginal Corporation v Edwards,[43] HREOC held that an Aboriginal community organisation was a ‘person aggrieved’ for the purposes of the complaint provisions which then existed under the RDA (the terms of which are substantially the same as those contained in s 46P of the HREOC Act). HREOC found that the respondents’ conduct had prejudicially affected the interests of the organisation in that it had hindered it from carrying out its objects.[44]

In Access For All Alliance (Hervey Bay) Inc v Hervey Bay City Council,[45] Collier J followed the decision of Mason J in Koowarta and held that a body corporate, including entities incorporated pursuant to the Associations Incorporation Act 1981 (Qld),[46] may be a ‘person aggrieved’ if, for example, the body corporate is treated less favourably based on the race, disability etc of its members, such as by being refused a lease of premises.[47] However, ‘merely incorporating a body and providing it with relevant objects does not provide it with standing it otherwise would not have had’.[48]

Her Honour also held that the interests of the members of an incorporated association are arguably irrelevant to determining whether the incorporated association is a ‘person aggrieved’ because it may sue or be sued in its own name.[49] However, her Honour left open the prospect of an incorporated association being sufficiently ‘aggrieved’ if all of its members were similarly aggrieved by the relevant conduct.[50] Alternatively, an incorporated association may be ‘aggrieved’ if it is a sufficiently recognised peak body in respect of the relevant issue, although her Honour suggested that this latter point was ‘of somewhat debatable significance’.[51]

Her Honour noted that in some cases courts have accepted that an incorporated association may have standing in human rights or environmental matters, although courts have typically applied principles as to standing strictly in such cases.[52]

(ii) Determining whether the ‘person aggrieved’ is the body corporate, its members or its directors

In IW v City of Perth,[53] a case brought under the Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (WA), the appellant (identified as IW) was a member of an incorporated association (PLWA) which had made an application for planning approval. The withholding of that planning approval was the subject of the complaint. Three members of the High Court held that the appellant was not a person aggrieved for the purposes of that Act. Dawson and Gaudron JJ stated:

It is clear from the structure of the Act generally ... that an ‘aggrieved person’ is a person who is discriminated against in a manner in which the Act renders unlawful. And when regard is had to the precise terms of the [goods and services section], it is clear that the person discriminated against is the person who is refused the services on terms or conditions or in a manner that is discriminatory ... there was no refusal of services in this case. And if anyone was the recipient of treatment which might constitute discrimination, it was the PLWA, not the appellant. Accordingly, the appellant was not an ‘aggrieved person’ within the meaning of that expression ... And that being so, he is in no position to assert that the City of Perth engaged in unlawful discrimination in the exercise of its discretion to grant or withhold planning approval for PLWA’s drop-in centre.[54]

Toohey and Kirby JJ, however, held that the appellant was an ‘aggrieved person’. Their Honours accepted that the benefit of the application for planning approval, if granted, would have gone to members of the PLWA and that the refusal was ‘in truth a refusal to provide [a service] to the members of PLWA’.[55] Toohey J noted that ‘[t]here was never any doubt that the application by PLWA was made on behalf of its members including the applicant’.[56]

In an earlier case, Simplot Australia Pty Ltd v Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission,[57] the complainant had alleged that she had been discriminated against on the basis of her sex because of the respondent’s decision to award a contract for transportation services to a male owned and operated business. At first instance the appellant had applied to HREOC for the matter to be struck out on the basis that, inter alia, as a company can have no gender, the complainant’s complaint was incapable of constituting sex discrimination. However, Commissioner Nettlefold rejected the application on the basis that the aggrieved person was, in fact, the personal complainant and not her company.

[I]t would be open to the Commission to find at the hearing that the decision to award the contract to a male owned and operated business and to reject the application of the complainant’s organisation supported, as it was, by comments arguably wrong in fact and sexist, fall within the definition of ‘discrimination’ in s 5(1) of the [SDA]. The definition would be applied simply on the basis that the aggrieved person was the complainant and not her company. On that basis, the fact that the company does not have a gender is a relevant fact, no doubt, but it is not necessarily a decisive fact. It might be seen as a conduit through which the respondent’s discriminatory act flowed to and adversely affected the complainant.[58] (original emphasis)

The respondent sought judicial review of HREOC’s decision. On review, Merkel J held that Commissioner Nettlefold had not erred in law in rejecting the strike out application, saying that:

Whether the act alleged ... constituted discrimination against an individual or against a corporation is a question of fact which remains to be determined. [The complainant’s] complaint is that she was discriminated against in the selection by Edgell of the company which was to perform work under a contract for transportation services. The discrimination alleged by her is that on the ground of her sex a company other than the company offered or nominated by her was engaged to carry out the required transportation services. In his decision the Inquiry Commissioner was conscious of the distinction between treatment of an individual and of a corporation and no error of law was made by him in that regard.[59] (original emphasis)

In Executive Council of Australian Jewry v Scully[60] (‘Scully’), a complaint was brought to HREOC by the Executive Council of Australian Jewry (‘the Council’). The Council is an unincorporated association whose members are Jewish community councils from across Australia and whose affiliates are national organisations with ‘an interest in a particular aspect of Judaism’.[61] The complaint related to the distribution by the respondent of material said to be offensive to Jewish people in breach of s 18C of the RDA which proscribes racial hatred. The impugned act took place in Launceston. HREOC Commissioner Nettlefold had dismissed a complaint brought by the Council under the RDA on the basis that the applicant lacked standing.[62]

One issue in the matter was whether a complaint could be brought by an unincorporated association. Wilcox J held:

I agree with Commissioner Nettlefold that, as Executive Council for Australian Jewry is not a ‘person’ in the eyes of the law, it is incapable of being a ‘person aggrieved’ within the meaning of s 22(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act. Therefore it is not itself a competent complainant. However, this does not mean its complaint is a nullity. It is necessary to go behind the name and consider whether the juristic persons who constitute the unincorporated association are ‘persons aggrieved’ by the allegedly unlawful act. If they are, the complaint is competent because in law, though not in name, it was made by them.[63]

His Honour continued:

Although it is not necessary to reach a firm view about the matter, it is strongly arguable that, considered individually, the constituents of the Council that represent Jewish communities outside Tasmania do not have a sufficient interest to meet the statutory test. However, I think the Hobart Hebrew Congregation clearly has the requisite interest... the constituents of the Council ‘are, in each instance, the elected representative organisation of the Jewish communities in each Australian State and the ACT’. It is apparent, therefore, that, despite its name, the Hobart Hebrew Congregation represents the Jewish community throughout Tasmania, including in the Launceston district. If there is truth in the allegations made against Ms Scully, her actions must have had a special impact on members of the Launceston Jewish community. According to the complaint, some of those people received Ms Scully's material in their letter boxes. Probably all of them have come into contact with non-Jews who have received the material and whose attitude to Jews may thereby have been adversely affected. It seems beyond contest that, if the acts occurred, they affected members of the Launceston Jewish community in a manner different in kind to the way they affected non-Jews, or even Jews living outside the Launceston area. Given the recognition in the authorities of the entitlement of representative bodies to obtain relief on behalf of members who have a special interest in a matter, I see no reason to doubt that the Hobart Hebrew Congregation is a ‘person aggrieved’ by the alleged acts.

If the Hobart Hebrew Congregation could make a competent complaint under s 22(1)(a) of the [RDA[64]] in its own name, it seems to me the Council (through its members) also may do so. As the Hobart Hebrew Congregation is a constituent of the Council, the Council represents at the national level those members of the Launceston Jewish community who were specially affected by Ms Scully's actions. Of course, the Council is not itself a ‘person’, it is an agglomeration of ‘persons’, so any complaint is legally the complaint of its members. In their representative role, if not on an individual basis, those persons were ‘persons aggrieved’ by the alleged unlawful acts. In my opinion, the case falls within para (b) of s 22 (1) of the [RDA[65]].[66]

In Access For All Alliance (Hervey Bay) Inc v Hervey Bay City Council,[67] Collier J agreed with the view taken by Wilcox J in Scully that whilst an unincorporated association cannot itself be an aggrieved person, a complaint brought by an unincorporated association may be valid if the members who comprise the unincorporated association are ‘aggrieved persons’ for the purposes of the HREOC Act.[68]

(d) Complaints in respect of deceased persons

In Stephenson (as executrix of estate of Dibble) v Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission[69] (‘Stephenson’), Wilcox J (Jenkins and Einfeld JJ agreeing) held that a complaint brought under the former complaint provisions of the SDA survived the death of a complainant.[70] A significant reason for the decision was that a contrary view would frustrate the broad societal objects of the SDA.

In Cuna Mutual Group Ltd v Bryant,[71] after considering the decision in Stephenson, Branson J held that where a person dies before filing a claim, a complaint could not be brought on behalf of the deceased person under the DDA.

While these decisions were determined prior to the complaint provisions being amended and moved from the unlawful discrimination acts to the HREOC Act,[72] they may still be relevant to the substantially similar provisions now operating.

6.2.2 Respondents

In Grigor-Scott v Jones,[73] the Full Federal Court held that a complaint lodged pursuant to s 46P of the HREOC Act must be against a person and that a person may be an individual or an entity that has a legal personality. In that case, the complaint was treated by HREOC as having been made against a Church that was an unincorporated body. The Full Court noted, but did not have to decide, that the complaint may, for this reason, not have been competent.[74]

6.2.3 Representative complaints to HREOC

The HREOC Act allows a representative complaint to be made pursuant to s 46P(2)(c) of the HREOC Act in the following circumstances:[75]

- the class members have complaints against the same person;

- all the complaints are in respect of, or arise out of, the same, similar or related circumstances; and

- all the complaints give rise to a substantial common issue of law or fact.

‘Representative complaint’ is defined under the HREOC Act to mean ‘a complaint lodged on behalf of at least one person who is not a complainant’.[76] ‘Class member’ is relevantly defined as ‘any of the persons on whose behalf the complaint was lodged, but does not include a person who has withdrawn under s 46PC’.[77]

In making a representative complaint to HREOC, a complainant need not name all the class members, or specify how many members there are to the complaint.[78] Furthermore, the complaint may be lodged with HREOC without members’ consent.[79] However, class members may, in writing to the President of HREOC, withdraw from a representative complaint prior to the termination of a complaint (after which they will be entitled to make their own complaint),[80] and the President may, on application in writing by an ‘affected person’, replace ‘any complainant with another person as complainant’.[81] The President may also, at any stage, direct that notice of any matter to be given to a class member or class members.[82]

Representative proceedings may also be brought in the Federal Court pursuant to the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (see 6.6.1(c) below).

6.3 Interim Injunctions

6.3.1 Section 46PP of the HREOC Act

Section 46PP of the HREOC Act empowers the FMC and the Federal Court to grant interim injunctions in respect of a complaint lodged with HREOC upon an application from HREOC,[83] a complainant, respondent or affected person. Section 46PP provides:

46PP Interim injunction to maintain status quo etc

(1) At any time after a complaint is lodged with the Commission, the Federal Court or the Federal Magistrates Court may grant an interim injunction to maintain:

(a) the status quo, as it existed immediately before the complaint was lodged; or,

(b) the rights of any complainant, respondent or affected person.

(2) The application for the injunction may be made by the Commission, a complainant, a respondent or an affected person.

(3) The injunction cannot be granted after the complaint has been withdrawn under section 46PG or terminated under section 46PE or 46PH.

(4) The court concerned may discharge or vary an injunction granted under this section.

(5) The court concerned cannot, as a condition of granting the interim injunction, require a person to give an undertaking as to damages.

The decision by a court as to whether or not to grant an interim injunction under s 46PP has been described as:

not an easy one because clearly there is a duty to look at the background information, the evidence presented, to determine what the status quo is, whether it should be preserved by the granting of an interim injunction, and to also have regard to the rights of a respondent.[84]

6.3.2 Principles governing determination of whether to grant an injunction

The principles that govern determination of applications under s 46PP are the principles that apply at common law to the granting of interim relief, ‘though in applying the principles to the exercise of the court’s discretion under s 46PP, the court should not regard itself as constrained solely by those common law principles’.[85] The common law principles that have been adopted in s 46PP cases by the Federal Court and the FMC include the following requirements: [86]

- that there is a serious issue to be tried between the parties; and

- that on the balance of convenience it is appropriate for the court to make the order.

This requirement has been held to involve consideration of whether there is an arguable case.[87] In De Alwis v Hair,[88] Bryant CFM refused the application for an injunction because his Honour concluded that there was no arguable basis on which a Court could grant the substantive relief sought by the applicant.

The types of factors considered as relevant to determining where the balance of convenience lies include:

- whether an award of damages would be a sufficient remedy;[89]

- in employment cases where an applicant seeks an injunction to prevent their termination the Court will consider whether the employment relationship has broken down and if it has whether it can be restored,[90] as well as the appropriateness or desirability of reinstatement during the interim period;[91]

- the effect that the granting of an interim injunction under s 46PP is likely to have on the business or operations of the respondent;[92] and

- the necessity of making an order.[93]

6.3.3 Ex parte injunctions

Where an application is made for an interim injunction on an ex parte basis, the applicant would need to establish that there is an element of urgency; and

- (i) proceeding inter partes would cause irreparable damage; or

- (ii) notice to the other party will of itself cause harm. [94]

There must be strong evidence, particularly to support an allegation that notice to the other party will of itself cause harm.[95]

Injunctive relief may also extend to persons who are not, or are not yet, party to the complaint before HREOC.[96]

In Harcourt v BHP Billiton Iron Ore Pty Ltd,[97] the applicant made an application for an interim injunction on an ex parte basis, prior to the finalisation of the complaint at HREOC . Lucev FM refused the application, taking into account the following factors:

- the respondents had not yet been made aware that the applicant had filed a complaint at HREOC ;

- there had not yet been any opportunity for the legal representatives of the parties to see whether an appropriate resolution of the issues could be reached, on either a temporary or permanent basis;

- there was no immediate danger, in Lucev FM’s view, of a relevant change in the status quo; and

- this was a matter which was more appropriately dealt with on an inter partes basis.

6.3.4 Types of orders that the Court can make under s 46PP

The power conferred by s 46PP is limited to orders that maintain the status quo as it existed immediately before the complaint was lodged or the rights of a complainant, affected person or respondent.

The power conferred by s 46PP has been said by the Federal Court to be limited to

the orders necessary to ensure the effective exercise of the powers of the Commission and the jurisdiction of the Court in the event of an application being made to the Court under the HREOC Act following the determination of a complaint.[98]

In AB v New South Wales Minister for Education & Training,[99] Raphael ACFM confirmed that the type of injunction which could be ordered under s 46PP(1)(a) was restricted to one which preserved the status quo immediately before the relevant complaint is lodged with HREOC[100] and that it existed to prevent rights from being taken away, not to create rights.[101]

This case concerned a 12-year-old boy who was the holder of a Bridging E Visa whilst awaiting the outcome of a substantive visa application that would give him permanent residency in Australia. He was offered a place at a selective high school - Penrith High School - subject to his complying with the condition that prior to enrolment he be an Australian citizen or permanent resident. The applicant lodged a complaint with HREOC alleging a breach of the RDA. The applicant applied to the FMC for the following orders under s 46PP:

- an order preventing the respondent from withdrawing the place offered at Penrith High School pending the determination of his HREOC complaint; and

- an order directing the respondent to allow the applicant to attend Penrith High School, pending the determination of his HREOC complaint.

Raphael ACFM held that ‘the status quo consists of the offer to the applicant of a place in the Penrith High School subject to his complying with the condition that prior to enrolment he be an Australian citizen or permanent resident’.[102] His Honour therefore refused to make either order sought by the applicant because both orders sought to achieve more than the maintenance of the status quo.[103]

In the case of order one it went beyond maintenance of the status quo because it would have the effect of holding open a place to a person who did not comply with the condition that prior to enrolment they be an Australian citizen or permanent resident.[104]

In the case of order two, his Honour held it went beyond maintenance of the status quo because the effect of the order would have been to have required the Minister to allow the applicant to attend a school that he was not attending prior to filing his complaint.[105]

In Hoskin v Victoria (Department of Education & Training),[106] the applicant sought orders pursuant to s 46PP(1)(b), inter alia, that the respondent provide to the applicant (or his lawyer) all documents supporting or relating to the decision to place the applicant on sick leave in August 2002 and the decision to maintain that position in October 2002. Walters FM concluded that the orders sought by the applicant could not properly be categorized as interim injunctions as they did not seek to ‘maintain’ any relevant ‘rights’ of the applicant.[107] His Honour stated:

In my opinion, the use of the word ‘maintain’ in section 46PP(1) emphasizes the temporary nature of the interim injunction referred to in the section and imports a requirement (at least in so far as section 46PP(1)(b) is concerned) that a pre-existing ‘right’ of a complainant, respondent or other affected person must have been adversely affected, or, alternatively, is likely to be adversely affected in the foreseeable future. The ‘rights’ of the complainant, respondent or other affected person ... must, in my view, be both continuing and substantive.[108]

Walters FM concluded that the orders, if they were to be granted, would do no more than operate to compel the respondent to perform a single, finite act – namely the production of the relevant documents. Accordingly, he dismissed the application.[109]

6.3.5 Duration of relief granted under s 46PP and the time period in which such relief must be sought

By reason of the combined operation of s 46PP(1) and (3), an interim injunction can only be granted under s 46PP during the period between the lodging of a complaint and the termination[110] or withdrawal[111] of a complaint.

A difference of opinion appears to have emerged in the cases as to whether the restrictions in s 46PP(3) mean:

- only that an application for an injunction under s 46PP must be made and determined prior to termination or withdrawal; or

- in addition, that the actual order must be limited so as to end upon termination or withdrawal.

In Rainsford v Group 4 Correctional Services[112] (‘Rainsford’), McInnis FM appeared to prefer the latter view, stating:

In the present case, I have noted that when an injunction is granted then it is only granted in accordance with 46PP(3) up until the date when a complaint is terminated. In the circumstances of this case there is no indication before this court as to when that might occur. Hence, it could hardly be said that any injunction this court might grant would be of a short-term duration. There is simply no guarantee of that fact.[113]

Heerey J stated in McIntosh v Australian Postal Corporation,[114] that the expression ‘interim injunction’ in s 46PP is

used in the New South Wales sense so as to include what Victorian lawyers would call an interlocutory injunction, that is an injunction until the trial and determination of an action...[115]

However, despite his Honour’s reference to ‘the trial and determination of an action’, the injunction sought in that matter was expressed so as to operate ‘until the Commission has completed an inquiry and conciliation process’.[116]

It would be incongruous if the HREOC Act was construed so as to potentially leave an applicant who obtains relief under s 46PP unprotected for the period between the time of the termination of their complaint by HREOC and the time at which that person was able to approach the Federal Court or FMC for interim relief under s 46PO(6). The better approach might therefore be that of Raphael FM in Beck v Leichhardt Municipal Council[117] where his Honour, having first noted the need to be ‘mindful that the relief granted [under s 46PP] must not be indeterminate’,[118] enjoined the respondent from terminating the applicant’s employment until seven days following the termination of his complaint to HREOC. His Honour further ordered that:

The parties shall have liberty to apply to this court for reconsideration of these orders in the event of a significant change in circumstances, including any significant delay in the procedures before the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.[119]

That form of order may be seen as a satisfactory means of avoiding the perceived difficulties raised by McInnis FM in Rainsford in the passage extracted above.

6.4 Election of Jurisdiction

Federal discrimination legislation does not purport to displace or limit the operation of State and Territory laws capable of operating concurrently with the SDA, RDA, DDA or ADA.[120] However, the SDA, RDA, DDA and ADA preclude a person from bringing a complaint under the federal legislation where a person has ‘made a complaint’, ‘instituted a proceeding’ or (in the case of the SDA and RDA only) ‘taken any other action’ under an analogous State or Territory law.[121]

In Elekwachi v Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission,[122] the applicant had initially made a complaint to HREOC under the RDA but had subsequently written to the South Australian Equal Opportunity Commission seeking that his complaint be referred to it. He sought judicial review of a decision by HREOC to decline his complaint under s 6A of the RDA on the basis that he had ‘made a complaint’ or ‘taken action’ under the Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (SA) and hence was precluded from making a complaint to HREOC.

Mansfield J held that the later letter requesting that the matter be determined by the South Australian Equal Opportunity Tribunal did not satisfy the requirements of a ‘complaint’ for the purposes of the Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (SA) and, as such, the South Australian Equal Opportunity Commissioner did not have any jurisdiction to inquire into the matter, or refer it for determination.[123] Accordingly, Mansfield J held that the later letter did not constitute ‘a complaint or any other action’ for the purposes of s 6A of the RDA.

In Barghouthi v Transfield Pty Ltd[124] (‘Barghouthi’), a case under the DDA, the respondent argued that the appellant was not entitled to make a complaint to HREOC as he had brought an unfair dismissal claim in the New South Wales Industrial Relations Commission in relation to the same factual circumstances. Hill J rejected that submission as the matter had not proceeded in the Industrial Relations Commission for want of jurisdiction saying:

Section 13(4) [of the DDA]...does not operate such that where one forum says that it has no jurisdiction the other ipso facto must be denied jurisdiction. As a matter of policy anti-discrimination legislation should not be read in a way that excludes the rights of claimants to have their cases heard in a court, whether it be State (or Territory) or Federal. Parliament cannot have intended that where a claimant makes a mistake in an application to a court leading to a finding of no jurisdiction in that forum that claimant is then excluded from rights altogether. Section 13(4) operates to ensure that where a claimant elects to bring an action in either the State or Federal jurisdiction that claimant is bound by the consequences of that election but that cannot be so if the claim is not in fact heard because the chosen forum lacks jurisdiction.[125]

In Price v Department of Education & Training (NSW)[126], the applicant first made a complaint to the Anti-Discrimination Board (‘ADB’) in respect of a matter of alleged disability discrimination. The ADB did not accept his complaint for investigation on the basis that ‘no part of the conduct complained of could amount to a contravention of a provision’ of the Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW).[127] The applicant then made a complaint in respect of the same matter to HREOC. The applicant submitted that s 13(4) of the DDA did not apply to his complaint as the ADB had declined his complaint on the basis that there was no contravention of the State Act.

Cameron FM rejected this argument and held that the fact that the complaint to the ADB was not well-made does not alter the fact that it met the criteria laid down by s 46P of the HREOC Act and thus s 13(4) of the DDA as well.[128] His Honour referred to the decision in Barghouthi and noted that in the present case, the ADB did not lack jurisdiction, it simply concluded that the complaint raised no conduct which could amount to contravention of the State Act. That being so, the applicant was not entitled to institute these proceedings and they must be dismissed’.[129]

In Ho v Regulator Australia Pty Ltd,[130] a case under the SDA, the respondent also applied to have the matter dismissed because the applicant had previously made an unfair dismissal and workers’ compensation claim to the New South Wales Industrial Relations Commission in relation to the same set of facts. Driver FM dismissed that application and held that those claims did not constitute ‘the institution of a proceeding or any other action in relation to a human rights matter’ for the purposes of s 11(4) of the SDA, even though the claim ‘had the same factual foundation’:

Both arose out of an alleged assault on [the applicant by the respondent]. The proceedings in the New South Wales Industrial Relations Commission related to a claim of unfair dismissal arising out of workplace harassment, but not sexual harassment. The claim for workers’ compensation had the same factual foundation. While there are some common facts, there was no claim of sex discrimination or harassment in the workers’ compensation claim or the Industrial Relations Commission proceedings (which were discontinued without a decision). Accordingly, ... s 11(4) of the SDA [does] not apply.[131]

6.5 HREOC Act is an Exclusive Regime

The procedure for the resolution of complaints of discrimination under the HREOC Act is an exclusive regime: it is clear that Courts will not grant remedies for discrimination unless persons have made a complaint to HREOC in accordance with that regime,[132] that complaint has been terminated[133] and a notice of termination has been issued under s 46PH(2) of the HREOC Act in respect of the complaint.[134]

In Re East; Ex parte Nguyen[135] (‘Nguyen’), the applicant sought a writ of certiorari and declaratory relief in the original jurisdiction of the High Court in respect of a criminal conviction for armed robbery. In part, the applicant argued that the absence of an interpreter constituted racial discrimination, contrary to s 9 of the RDA. The application was dismissed, the High Court describing the complaint provisions as then existed under the RDA (in substance the same as those now found in the HREOC Act) as an ‘elaborate and special scheme’ that was ‘plainly intended by the Parliament to provide the means by which a person aggrieved by a contravention of s 9 of the [RDA] might obtain a remedy’.[136] The Court held that the RDA ‘provides its own, exclusive regime for remedying contraventions’ and that, having not invoked that regime, the applicant did not have a right that could amount to a justiciable controversy.[137]

In Bropho v Western Australia[138] (‘Bropho’), the applicant had sought a declaration that the enactment of the Reserves (Reserve 43131) Act 2003 (WA) and actions subsequently taken pursuant to it contravened s 9 of the RDA and, as such, were of no effect. The applicant had not made a complaint of unlawful discrimination to HREOC under the HREOC Act, but had commenced proceedings directly in the Federal Court.

Nicholson J accepted that Nguyen was binding authority for the principle that the RDA and HREOC Act provide for an exclusive regime for the remedying of contraventions of the RDA. His Honour therefore struck out those aspects of the claim which sought remedies provided for under the HREOC Act.[139] However, the applicant’s argument as to constitutional invalidity based on s 9 of the RDA was able to be litigated without an application first being made to HREOC.[140] Applying Gerhardy v Brown,[141] his Honour held that ‘the issue of constitutional validity precedes the application of any remedy for a contravention’.[142]

The decision in Nguyen was also followed in Williams v Pardoe.[143] Bignold J dismissed an application to the Land and Environment Court in so far as it alleged racial discrimination under the RDA because, relying upon the decision in Nguyen, his Honour held that the HREOC Act provided an exclusive regime for remedying contraventions.[144]

6.6 Scope of Applications Made Under s 46PO of the HREOC Act to the FMC and Federal Court

6.6.1 Parties

Section 46PO(1) of the HREOC Act provides that:

(1) If:

(a) a complaint has been terminated by the President under section 46PE or 46PH; and

(b) the President has given a notice to any person under subsection 46PH(2) in relation to the termination;

any person who was an affected person in relation to the complaint may make an application to the Federal Court or Federal Magistrates Court alleging unlawful discrimination by one or more of the respondents to the terminated complaint.

Accordingly, while a person can bring a complaint to HREOC on behalf of another under s 46P(2)(c) of the HREOC Act, only ‘an affected person’ is entitled to make an application to the FMC or Federal Court.[145]

The HREOC Act defines an ‘affected person’ as being ‘in relation to a complaint, a person on whose behalf the complaint was lodged’.[146] As noted above, a complaint to HREOC may only be lodged by or on behalf of ‘a person aggrieved’. Hence an application made to the FMC or Federal Court pursuant to s 46PO(1) will only be able to be brought by ‘a person aggrieved’ by the alleged discrimination. Further, the Court can revisit a finding by HREOC that a person is a ‘person aggrieved’ and can dismiss an application if it determines that the applicant is not a ‘person aggrieved’.[147]

In Stokes v Royal Flying Doctor Service,[148] Mr Stokes lodged a complaint with HREOC on behalf of the Ninga Mia Christian Fellowship and the Wongutha Birni Aboriginal Corporation. When the matter came to the FMC, McInnis FM permitted Mr Stokes to amend the application by replacing the Fellowship and Corporation as the applicants with Mr Stokes and other named individuals. McInnis FM stated that the amendment ‘does no more than to identify, with greater specificity, the individuals who are now said to be part of the group which is said to be the subject of the complaint for discrimination’.[149] He commented that it would be ‘unduly technical in my view and inappropriate to impose, in a matter of this kind, particularly arising out of human rights legislation, an unduly technical interpretation of either corporate identity or identity of the group’.[150]

In several cases courts have held that an application can only be brought against a person if they were a respondent to the complaint to HREOC.[151] This means that any application that names a person who was not a respondent to a complaint can be summarily dismissed[152] and an application to join such a person will be refused.[153]

This issue was most recently considered by the Full Federal Court in Grigor-Scott v Jones[154] (‘Grigor-Scott’). In this case the Court set aside an order joining Mr Grigor-Scott to the primary proceedings because it found that he was not a respondent to the complaint made to HREOC and should therefore never have been joined.

The original complaint to HREOC did not nominate any person or entity as a respondent but simply alleged that a document described as ‘Bible Believers’ Newsletter # 242’ published on a website contravened provisions of Part IIA of the RDA but it.

The President of HREOC corresponded with Mr Grigor-Scott, a Minister of the Bible Believers’ Church (‘the Church’), about the complaint. Mr Grigor-Scott also attended the conciliation conference held by HREOC in relation to the complaint. Despite this, the letter from the President to Mr Jones enclosing copies of correspondence from Mr Grigor-Scott referred to the correspondence as being from Mr Grigor-Scott ‘on behalf of the respondent’. Further the termination notice named the Church as the respondent and the President’s reasons for decision accompanying the termination notice referred to the Church as the respondent.

When Mr Jones filed his original application with the Court he named the Church as the respondent but he subsequently applied and was granted an order joining Mr Grigor-Scott as a respondent.

Mr Jones argued that when identifying the respondent to a complaint the court should consider the subject matter of the complaint and determine who the complaint in substance is about.

The Full Court whilst noting the complaint was about the website, focussed instead on consideration of whom the complainant, HREOC and the President of HREOC treated as the respondent when determining whether Mr Grigor-Scott was a respondent. On the basis of the evidence the Full Court held that the complainant, HREOC and the President treated the complaint as having being made against the Church not Mr Grigor-Scott and as such Mr Grigor-Scott was never a respondent to the original complaint.[155]

The Full Court also dismissed the proceedings brought against the Church. It did so because, as the Church was not a legal entity, it could not be sued and any proceedings against it were therefore incompetent.[156]

(c) Representative proceedings in the Federal Court

The Federal Magistrates Act 1999 (Cth) (‘Federal Magistrates Act’) does not enable representative proceedings to be brought in the FMC. Representative complaints can therefore only be pursued in the Federal Court.

Part IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (‘Federal Court Act’) enables representative complaints to be commenced in the Federal Court by one or more of the persons to the claim as representing some or all of the other persons, if:

- (a) seven or more persons have claims against the same person;[157]

- (b) the claims of all those persons are in respect of, or arise out of, the same, similar or related circumstances;[158] and

- (c) the claims of all those persons give rise to a substantial common issue of law or fact.[159]

Note that while a complaint can be lodged with HREOC on behalf of a ‘person aggrieved’ (see 6.2.3 below), representative proceedings can only be commenced in the Federal Court by at least one ‘person aggrieved’ who has had their claim terminated by HREOC. As noted above, under s 46PO(1) of the HREOC Act, upon termination of a complaint by the President only ‘an affected person’ may make an application to the Federal Court.[160] Furthermore, s 33D(1) of the Federal Court Act provides that only a person who has ‘sufficient interest’ to commence a proceeding against the respondent on his or her own behalf has standing to bring a representative proceeding against the respondent on behalf of other persons who have the same or similar claims against the respondent.[161]

6.6.2 Relationship between application and terminated complaint

Section 46PO(3) of the HREOC Act places limitations, related to the terminated complaint, upon the nature and scope of applications that may be made to the Federal Court and FMC. The section provides that:

(3) The unlawful discrimination alleged in the application:

(a) must be the same as (or the same in substance as) the unlawful discrimination that was the subject of the terminated complaint; or

(b) must arise out of the same (or substantially the same) acts, omissions or practices that were the subject of the terminated complaint.

In Charles v Fuji Xerox Australia Pty Ltd,[162] Katz J explained the operation of paragraphs (a) and (b) of s 46PO(3) as follows:

Paragraph (a) of subs 46PO(3) of the [HREOC Act] proceeds on the basis that the allegations of fact being made in the proceeding before the Court are the same as those which were made in the relevant terminated complaint. The provision naturally permits the applicant to claim in the proceeding that those facts bear the same legal character as they were claimed in the complaint to bear. However, it goes further, permitting the applicant to claim in the proceeding as well that those facts bear a different legal character from that they were claimed in the complaint to bear, provided, however, that the legal character now being claimed is not different in substance from the legal character formerly being claimed.

Paragraph (b) of subs 46PO(3) of the [HREOC Act], on the other hand, permits the applicant to allege in the proceeding before the Court different facts from those which were alleged in the relevant terminated complaint, provided, however, that the facts now being alleged are not different in substance from the facts formerly being alleged. It further permits the applicant to claim that the facts which are now being alleged bear a different legal character than the facts which were alleged in the complaint were claimed to bear, even if that legal character is different in substance from the legal character formerly being claimed, provided that that legal character ‘arise[s] out of’ the facts which are now being alleged.[163]

His Honour also favoured a construction of the sub paragraphs of s 46PO(3) that does not permit an applicant to rely on acts of discrimination which occur after the complaint has been lodged with HREOC.[164] His Honour held that this conclusion was consistent with ‘the policy of the [HREOC Act] in ensuring that there exists an opportunity for the attempted conciliation of complaints before they are litigated’.[165]

The provisions of s 46PO(3) were further considered in Travers v New South Wales[166] (‘Travers’), in which Lehane J confirmed that an application to the Federal Court cannot include allegations of discrimination which were not included in the complaint made to HREOC. Nevertheless, his Honour noted that:

the terms of s46PO(3) suggest a degree of flexibility (‘or the same in substance as’, ‘or substantially the same’) and a complaint, which usually will not be drawn by a lawyer, should not be construed as if it were a pleading.[167]

Lehane J also observed that the initial complaint may be quite brief and the details later elicited during investigation.[168] Although it was unnecessary for his Honour to express a final view on the issue, his Honour indicated that he disagreed with a submission put by the respondent to the effect that the term ‘complaint’ (in the context of s 46PO(3)) was limited to the initial letter of complaint to HREOC. His Honour appeared to prefer the contrary submission put by the applicant, stating:

it may be that the ambit of the complaint is to be ascertained, for the purpose of s 46PO(3), not by considering its initial form but by considering the shape it had assumed at its termination.[169]

Although not making reference to the decision in Travers, a similar approach to the requirements of s 46PO(3) was taken by Driver FM in Ho v Regulator Australia Pty Ltd.[170] His Honour ruled that the scope of the proceedings was to be determined by the complaint as terminated by HREOC, including any amendments which may have been made to the complaint while the matter was before HREOC, rather than the original terms of the complaint to HREOC.[171]

Driver FM also took this approach in Hollingdale v Northern Rivers Area Health Service,[172] where his Honour stated that:

The task for the Court is to determine the parameters of the complaint that has been terminated. The documents on which that determination may properly be based include, but are not necessarily limited to, the notice of termination and accompanying letter from the President [of HREOC], and the terms of the document or documents setting out the complaint or complaints to HREOC.[173]

Driver FM upheld the respondent’s application to strike out the claim of disability harassment made by the applicant as it had not formed part of her complaint to HREOC. In finding that the applicant had not made a complaint of disability harassment to HREOC, his Honour considered it ‘significant that the letter from [HREOC terminating the complaint] makes no reference at all to harassment’, saying it indicated that ‘HREOC did not regard the complaint as including a complaint of harassment’.[174] In any event, his Honour said that, if he was wrong and the complaint had intended to make a complaint about disability harassment, ‘it was not seen as such by HREOC and it has not been terminated’.[175]

In Gama v Qantas Airways Ltd,[176] Raphael FM held that in order to satisfy the requirement set out in s 46PO(3)(b):

it is not enough that it arises out of the same general allegation. There must be a close connection between what was told to the Commission and what is alleged in the court proceedings. A new incident, even if it is an incident of the same type as advised to the Commission, would be unlikely to pass this test because, if unknown at the time of the attempted conciliation, it could not have been part of it. Difficulties will arise where a complaint to the Commission lacks details or is expressed in general forms, eg by saying words to the effect ‘frequently during a particular period I was subjected to verbal abuse about my sex/disability/race/age’. What if the applicant identifies four such incidents before the Commission but then recalls another before the court? I think it would be for the court to decide whether the evidence given arises out of the same practice that was the subject of the terminated complaint.[177]

In Bender v Bovis Lend Lease Pty Ltd,[178] the respondent sought an interim order striking out certain paragraphs of an affidavit supporting the applicant’s claim of sexual harassment, on the basis that the discrimination alleged in the paragraphs did not form part of the complaint to HREOC as required by s 46PO(3). McInnis FM held that the Court has a discretion to at least consider whether to strike out certain parts of an affidavit prior to hearing as it is important to ensure that the applicant complies with the requirements of s 46PO(3). Considering this matter at an early stage, as opposed to leaving it to trial ensures that ‘issues are properly identified consistent with the obligations of the Court in considering the unlawful discrimination alleged in this application compared with the discrimination which was the subject of the terminated complaint’.[179]

6.6.3 Validity of termination notice

In Speirs v Darling Range Brewing Co Pty Ltd,[180] two of the respondents sought an order that the proceedings against them be summarily dismissed on the ground that a termination notice issued by HREOC was invalid and/or a nullity. While the initial complaint to HREOC raised allegations against those persons, the President’s notice of termination did not refer to those persons as respondents to the complaint. The President of HREOC subsequently issued a second notice of termination which did name those persons as respondents.

The two respondents submitted that the second notice was a nullity and that accordingly the Court did not have jurisdiction to hear and determine the claims made against them. McInnis FM accepted that submission. His Honour’s reasons were as follows:

In my view there does not appear to be any power given to HREOC in the legislation to issue a further termination notice arising out of the same complaint. Once issued and respondents named then those respondents so named who were given an opportunity to participate in the procedure and the opportunity to at least conciliate the complaint before litigation means that in the circumstance of the present case the denial to the respondents of that opportunity itself would demonstrate a flaw in the process followed by HREOC in this instance. It is not possible in my view for HREOC to simply retrospectively issue a further notice in circumstances where the purported respondents to that notice have not in truth and in fact been able to participate in the conciliation process which the President is bound to follow in accordance with the provisions of the HREOC Act to which I have referred.

There is also no provision in my view for HREOC to issue an amended notice of termination and this is particularly so after the time has elapsed for the first notice to be revoked pursuant to s 46PH(4) of the HREOC Act. It would be unusual if a further notice could be issued after proceedings had been commenced in the Federal Court arising out of the same complaint and in circumstances where in s 46PF(4) the legislature provides that a complaint cannot be amended after it has been terminated by the President under s46PH. Therefore to issue a second notice simply at the request of solicitors for the complainant in circumstances where all that has been requested is the naming of further respondents who had not been given an opportunity to participate in the inquiry effectively amounts to an amendment of the termination notice to include other parties. If the termination notice itself cannot be revoked then it is difficult to see how either an amendment can occur or a further notice issued once Court proceedings have been commenced in relation to the complaint.[181]

6.6.4 Pleading claims in addition to unlawful discrimination

In Thomson v Orica Australia Pty Ltd (No 2)[182] an issue arose as to whether a claim for damages for breach of contract was being pursued by the applicant in addition to the unlawful discrimination claim.

It had not been explicitly stated in the points of claim filed by the applicant that the applicant was arguing the case on any other basis than a breach of the SDA. However at the close of evidence, in answer to a question by Allsop J, counsel for the applicant stated that if no breach of the SDA was found by the Federal Court, her client made a claim for damages for repudiation of the contract of employment.

In subsequently filed written submissions, counsel for the respondent submitted that the matter had always been ‘in the context of Commonwealth legislation’[183] and that the respondent was ‘seriously disadvantaged’[184] by the perceived shift in the case presented by the applicant. The respondent further contended that if the applicant had specified at the outset that she was seeking damages for breach of contract, the approach of the respondent would have been different in a number of ways.

Allsop J stated he had ‘real difficulty’[185] in seeing what further evidence may have been led, or what further cross-examination of the applicant may have taken place, in the context of an allegation of repudiation in contract and an associated claim for damages as opposed to an allegation of repudiation of the employment contract in the context of the SDA. However, his Honour made orders allowing for the respondent to seek further and better particulars of the points of claim, for additional evidence to be filed by the applicant and for further cross examination.

A court will, however, only be able to deal with claims in addition to unlawful discrimination if it falls within its jurisdiction. In Artinos v Stuart Reid Pty Ltd,[186] Driver FM refused the applicant’s application to join an additional respondent because the claim against the additional respondent was a claim of defamation and the Court did not have the jurisdiction to deal with such a claim.[187]

6.7 Relevance of Other Complaints to HREOC

6.7.1 ‘Repeat complaints’ to HREOC

In McKenzie v Department of Urban Services,[188] Raphael FM considered whether or not a person could bring a case before the FMC if the subject matter of the complaint was a ‘repeat’ complaint. The applicant had made complaints to HREOC in 1997 and 1998, which were dismissed on the basis that there was no evidence or no sufficient evidence of discrimination. The applicant made an application for an order of review pursuant to s 5 of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) in relation to the dismissal but subsequently discontinued the proceedings. The applicant then made a further complaint to HREOC in November 1999 which was terminated by HREOC on the basis that, amongst other things, the complaint had already been dealt with. The applicant subsequently made an application to the FMC under s 46PO of the HREOC Act.

The respondent argued that the applicant was stopped from hearing the matter by virtue of the fact that it had already been dealt with by HREOC. Raphael FM considered a number of authorities on the issue of estoppel and res judicata in relation to administrative decisions.[189] His Honour concluded that there was nothing to prevent the applicant from having her case heard pursuant to s 46PO of the HREOC Act. His Honour found:

It may be argued against this finding that it will open the floodgates to applicants who were unhappy about previous decisions of HREOC not to grant them an inquiry into their complaint. Such a person would make a further application to HREOC which would make a finding that it would not proceed because the events in question took place more than twelve months prior thereto and had already been the subject of consideration. That decision would have the effect of terminating the complaint, and upon receipt of the notice of termination the Applicant could proceed to this Court. Although this Court could make an order under s 46PO(4)(f), it could not do so until after it had made a finding of unlawful discrimination, and would therefore be obliged to hear the complaint in its entirety. I was not provided with any authority, either in support of the proposition put by Ms Donohue or by Ms Winters as to why, if I made the finding which I have made, the consequences would not be as I have outlined. I can find no authority either, and it may well be that the Act needs to be amended by the addition of a section similar to s 111(1) of the Anti-Discrimination Act (NSW), to prevent a spate of hearings in cases where the Respondent has reasonably thought that its involvement was at an end some considerable time ago.[190]

The relevance of repeat complaints in unlawful discrimination proceedings is different to that of the provisions relating to vexatious litigants or vexatious proceedings.

Note, however, that both the Federal Court Rules and the FMC Rules contain provisions relating to vexatious litigants. Order 21 of the Federal Court Rules and r 13.11 of the FMC Rules enable a court to limit the ability of persons found to have ‘habitually, persistently and without reasonable grounds instituted proceedings in the Court or any other Australian court’ to continue or institute proceedings.

In Lawrance v Watson,[191] Cameron FM noted that while the applicant had commenced at least six proceedings in the Federal Magistrates Court against some or all of the respondents in the present case concerning similar allegations of discrimination, this did not necessarily mean that the applicant was a vexatious litigant. In Cameron FM’s view, as there had not yet been a judgment in most of the proceedings, the applicant’s claims against the various respondents to these proceedings remained, at this point, essentially untested. By contrast, a vexatious litigant was one who repeatedly litigated an issue which had already been the subject of a judgment.

However, in a later decision concerning the same applicant, Lawrance v Macarthur Legal Centre,[192] Scarlett FM was satisfied that orders should be made to prevent the applicant from commencing or continuing proceedings against two of the respondents against whom she had brought six sets of proceedings in the space of two years.[193] His Honour cited Ramsey v Skyring[194]in which Sackville J held that the expression ‘habitually and persistently’ appearing in O 21 r 1 of the Federal Court Rules implies more than ‘frequently’. Scarlett FM was satisfied that the test of ‘habitually and persistently’ had been met. His Honour declined to make an order in relation to another of the respondents who had been a respondent in proceedings commenced by the applicant on only two occasions (although the applicant had sought, unsuccessfully, to have them joined in three other proceedings).

In addition, both the Federal Court Rules and the FMC Rules permit a Registrar to refuse to accept a document which appears to the Registrar on its face to be an abuse of the process of the Court or to be ‘frivolous or vexatious’ for filing.[195] Under the FMC Rules the Registrar can also refuse to accept a document for filing if it appears on its face to be ‘scandalous’.[196]

Under the Federal Court Rules a Registrar may also seek a direction from a Judge as to whether to accept a document (there is no equivalent provision in the FMC Rules).[197] In Paramasivam v Randwick City Council,[198] Justice Sackville held that an applicant’s litigious history is irrelevant to determining whether to refuse to accept a document or to seek a direction under Order 46 rule 7A of the Federal Court Rules, as determination of these matters had to be made on the basis of the document on its face.

6.7.2 Evidence of other complaints to HREOC

In Paramasivam v Jureszek,[199] the respondent attempted to adduce evidence relating to other complaints made by the applicant of racial discrimination against a number of other parties in differing circumstances. Gyles J refused to admit that material on the basis that it was not probative of any issue in the case, particularly given that the applicant’s credit was not in issue. His Honour also indicated that, even if the applicant’s credit had been in issue, he would have been reluctant to admit that material, given that the circumstances in which propensity evidence can be given are limited. To be of any value, the Court would have to examine the bona fides and merits of each complaint. The mere fact that a court or another regulatory authority had rejected those complaints would not establish any relevant fact in the proceedings.

6.8 Pleading Direct and Indirect Discrimination as Alternatives

Although the grounds of direct and indirect discrimination have been held to be mutually exclusive,[200] an incident of alleged discrimination may nonetheless be pursued by an applicant as a claim of direct or indirect discrimination, pleaded as alternatives.

In Minns v New South Wales[201] (‘Minns’), the applicant alleged direct and indirect disability discrimination by the respondent. The respondent submitted that the definitions of direct and indirect discrimination are mutually exclusive and that the applicant therefore had to elect whether to pursue her claim as a claim of direct or indirect discrimination. In rejecting that submission Raphael FM stated that:

The authorities are clear that [the] definitions [of direct and indirect discrimination] are mutually exclusive (Waters v Public Transport Corporation (1991) 173 CLR 349 at 393; Australian Medical Association v Wilson (1996) 68 FCR 46 at 55 [‘Siddiqui’s case’]). That which is direct cannot also be indirect ...[202]

That statement means that the same set of facts cannot constitute both direct and indirect discrimination. It does not mean that a complainant must make an election. The complainant can surely put up a set of facts and say that he or she believes that those facts constitute direct discrimination but in the event that they do not they constitute indirect discrimination. There is nothing in the remarks of Sackville J in Sidddiqui’s case which would dispute this and the reasoning of Emmett J in [State of NSW (Department of Education) v HREOC [2001] FCA 1199] and of Wilcox J in Tate v Rafin [2000] FCA 1582 at [69] would appear to suggest that the same set of facts can be put to both tests.[203]

Similarly, in Hollingdale v Northern Rivers Area Health Service,[204] a case under the DDA, the respondent sought to strike out that part of the applicant’s points of claim that sought to plead the same incident in the alternative as direct and indirect discrimination. The respondent argued that the complaint terminated by HREOC appeared to only concern direct discrimination. Driver FM rejected the respondent’s argument, finding that the applicant is not ‘bound by the legal characterisation given to a complaint by HREOC’, and stating that ‘[t]hat is especially so when more than one legal characterisation is possible based on the terms of the complaint’.[205] His Honour continued:

There is, in my view, no obligation upon an applicant to make an election between mutually exclusive direct and indirect disability claims. If both claims are arguable on the facts, they may be pleaded in the alternative. The fact that they are mutually exclusive would almost inevitably lead to a disadvantageous costs outcome for the applicant, but that is the applicant’s choice.[206]

6.9 Applications for Extension of Time