Chapter 3: Remote Indigenous education: Social Justice Report 2008

Social Justice Report 2008

Chapter 3: Remote Indigenous education

![]() Download in PDF

Download in PDF

![]() Download in Word

Download in Word

- Part 1: Introduction

- Part 2: Setting the scene – the challenge of delivering a quality educational service in remote Australia

- Part 3: School and community partnerships

- 1 The state cannot do it on its own and neither can remote communities

- 2 How do we form education partnerships?

- Case Study 1 – Graham (Polly) Farmer Foundation: A partnership model for remote communities

- 3 What is success in remote education?

- Case Study 2 – Maningrida School: Education and training with a focus on achieving success in the region

- Case Study 3 – Garrthalala: Success in a remote school

- 4 Developing local forums

- 5 Integrating industry and philanthropic groups in education programs

- 6 Summary of issues: School and community partnerships

- Part 4: The best and brightest teachers and leaders

- 1 Indigenous leaders and educators

- 2 Employment mentors

- 3 Teacher recruitment strategies

- 4 Placement of trainee teachers in remote schools

- 5 Teacher scholarship schemes

- 6 Professional development and industry release

- 7 Remote allowances

- 8 Teacher retention and living conditions

- 9 Discriminatory housing policy for Indigenous teachers

- 10 Marketing incentives

- 11 Summary of issues: The best and brightest teachers

- Part 5: Early childhood education

- Part 6: Education as the key to other life chances

- Part 7: Conclusion and recommendations

Part 1: Introduction

...education is the engine room of prosperity and helps create a fairer, more

productive society. It is the most effective way we know, to build prosperity

and spread opportunity...[1]

In recent decades, academics, policy makers and education experts have

debated the pros and cons of various education approaches aimed at improving

educational outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (or

indigenous peoples). For the most part, the debates have focussed on Indigenous

education in remote Australia. This is where Indigenous students make up the

majority of the school populations, and the schools they attend are not

considered, (and often not funded) in the same way as ‘mainstream’

schools. The Indigenous students in these remote schools often experience

significant educational disadvantage, and as a consequence, their English

literacy and numeracy skills are at lower levels than other Australian students.

With few exceptions, the debates about Indigenous education focus on whether

it is better to educate Indigenous children in their own communities or whether

it is better to remove Indigenous children to boarding schools where they can

access western style education and be saturated in the English language. The

debates contest strategies that, on the one hand, seek to

‘normalise’ Indigenous students through assimilation and integration

with mainstream society, and on the other, seek to preserve Indigenous languages

and culture within Indigenous communities. The proponents of both sides of the

argument are keen for the same outcomes – the best possible education and

the best possible life opportunities for remote students.

During 2007 and 2008 the Australian media reflected these polarising themes.

We saw articles on subjects such as: ‘boarding school education versus

education in the home community’; ‘bilingual education versus

English literacy saturation’; ‘education partnerships with

Indigenous communities versus education dictated by the mainstream’; and

the ‘regionalisation of education resources versus education in the

homelands.’[2]

It is my contention that these debates are a distraction from the fundamental

requirements for good Indigenous education policy and services. The focus on

education approaches is a distraction from a simple truth; that there are some

very large gaps in the provision of education services in remote Australia.

Debates about approaches draw attention away from the fact that many remote

Indigenous students receive a part-time education in sub-standard school

facilities - if they receive a service at all.

If students across the country are assessed using the same tests and deemed

to be educationally competent or otherwise using the same measures, then

governments must provide consistent levels of education resources across the

country. It is not possible, practical or desirable to move all remote students

into urban centres, so quality education must move to them. Governments must

also prepare for ongoing growth in Indigenous populations. For example, it is

estimated that the total population of the Northern Territory will increase by

87 percent by 2056. [3] Across

Australia the 2006 census tells us that the median age of the Indigenous

population was 21 years, compared to 37 years for the non-Indigenous

population.[4] In all we are a young

and growing demographic.

It is time for governments to assess the availability of education services

in remote Australia and ensure that quality education is available when

populations warrant them. This is the right of all Australian children, and in a

country as wealthy as ours, remote Indigenous students should receive no less.

The human right to education is characterised by four features. Education

must be available, accessible, acceptable and

adaptable.[5]

National Benchmark test results show a significant gap in the educational

performance of remote Indigenous students compared with students in all other

locations.[6] These results have not

changed over time. In fact, there have been negligible improvements in English

literacy and numeracy outcomes along with a simultaneous erosion of Indigenous

languages and culture.

This chapter will not reproduce statistics that point to student failure, nor

will it debate pedagogical approaches. My aim is to shine the spotlight on the

systems that provide and deliver education services. The issue I am interested

in interrogating here, is whether governments have fulfilled their obligation to

provide quality education services in remote Australia.

The Australian Government has indicated its willingness to improve the life

chances of Indigenous Australians through education. The Apology to the

Stolen Generations in 2008 contained strong commitments to early childhood

education.[7] The Close the Gap

Statement of Intent committed the Government to work with Indigenous people

to achieve equality in health status and life expectancy, comparable with

non-Indigenous Australians by 2030.[8] The Prime Minister recognises the importance of education in achieving equal

life chances. In the Apology he stated:

Our challenge for the future is to embrace a new partnership between

Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. The core of this partnership for the

future is closing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians on

life expectancy, educational achievement and employment

opportunities.[9]

I acknowledge that in population terms, the majority of Australian Indigenous

students are in urban and regional locations. I have chosen to dedicate this

chapter to discussion of remote Indigenous education because this is where the

greatest educational challenges exist. It is where we see the greatest

disadvantage and it is where we see the poorest educational outcomes.

This chapter contains specific measures focussed on the considerable

challenges of providing preschool, primary school and secondary school education

in remote Australia. It provides examples of initiatives which demonstrate good

practice and it concludes with recommendations for government action. The

chapter is structured in seven parts:

- Introduction

- Setting the scene – the challenge of delivering a quality

educational service in remote Australia - School and community partnerships

- The best and brightest teachers and leaders

- Early childhood education

- Education as the key to other life chances

- Conclusion and recommendations.

Part 2: Setting the scene – the challenge of

delivering a quality educational service in remote Australia

1 Remote Australia

The vast majority of the Australian continent is sparsely inhabited. In 2006

there were 1,187 discrete Indigenous communities in Australia with 1,008 of

these communities in very remote areas. Of the very remote communities, 767 had

population sizes of less than 50 persons. In 2006 there were 69,253 Indigenous

people living in very remote

Australia.[10]

31 percent of Indigenous Australians live in major cities and 24 percent live

in remote and very remote

Australia.[11] The remainder of the

Indigenous population lives in regional centres. In contrast, non-Indigenous

Australians are much more likely to live in major cities with less than 2

percent living in remote and very remote

areas.[12] The

Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia describes remote and very remote

locations as having very little accessibility of goods, services and

opportunities for social

interaction.[13] For ease of

expression from hereon, I will use the term ‘remote’ to include both

remote and very remote regions.

Remoteness has obvious implications for school education, limiting access to

educational services as well as other resources such as libraries and

information technology. Road access may be limited during times of the year and

during wet season periods there may be no access for months on end. If internet

access is available in remote Australia, it is usually via satellite, offering a

dial-up service with limited and slow internet speeds.

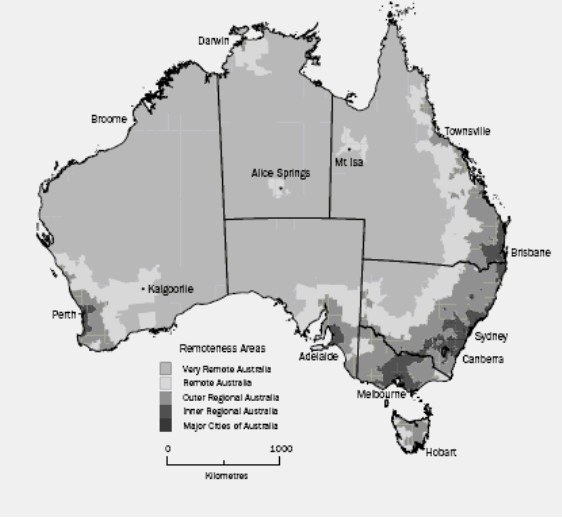

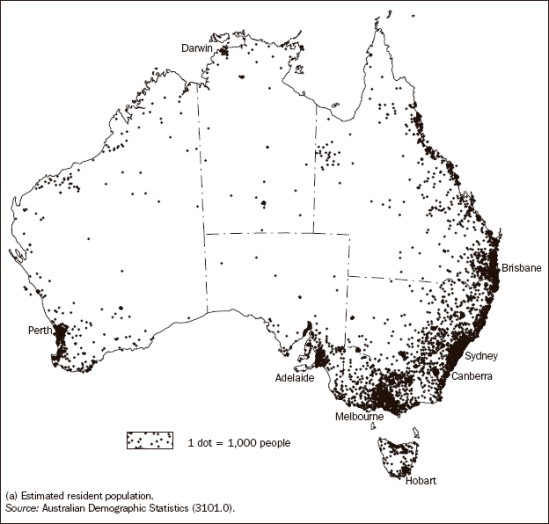

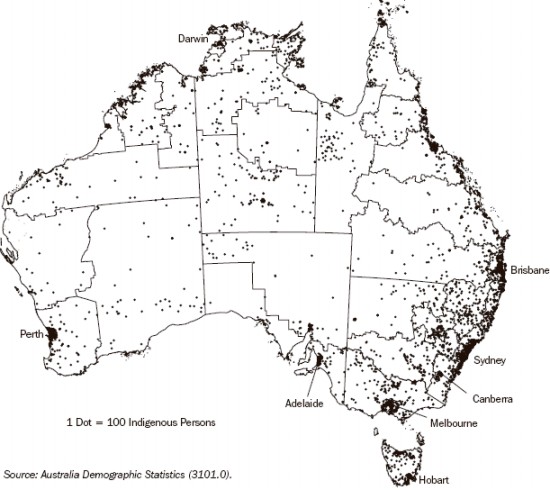

Map 1 shows the distribution of population across Australia varying from

Major Cities through to Very Remote Australia. Map 2 shows the distribution of

Australia’s total population across Australia with each dot representing

1,000 people and Map 3 shows the distribution of the Indigenous population

across Australia with each dot representing 100 people. Table 1 shows the

population of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people by remoteness category.

Map 1: Remoteness categories of the Australian continent - June 2006,

1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2008, Australian Bureau of Statistics

Map 2: Australian population distribution - June 2006, 1301.0 - Year Book

Australia, 2008, Australian Bureau of Statistics

Map 3: Indigenous population distribution - June 2006, 1301.0 - Year Book

Australia, 2008, Australian Bureau of Statistics

Table 1 Estimate of Indigenous and non-Indigenous population in Regions

according to 2006 Census

data[14]

| Pop. Region | Est. non Indigenous pop. | Est. Indigenous pop. |

|---|---|---|

| Major Cities of Australia | 13,996,450 | 165,804 |

| Inner Regional Australia | 3,975,154 | 110,643 |

| Outer regional Australia | 1,854,026 | 113,280 |

| Remote Australia | 267,199 | 47,852 |

| Very Remote Australia | 88,008 | 79,464 |

| Total | 20,180,837 | 517,043 |

2 Are education services available and accessible in

remote Australia?

We don’t have accurate information to assess whether remote Indigenous

students have access to education in their region. There is no data which

matches populations of school-aged students against preschool, primary and

secondary school services in Australia. This lack of data is a serious omission.

It is essential information for government’s to plan their expenditure in

education. This kind of data tells us whether Australia is meeting its

obligations under the Convention of the Rights of the Child to:

... recognize the right of the child to education, and with a view to

achieving this right progressively and on the basis of equal opportunity, they

shall, in particular:

- Make primary education compulsory and available free to all;

- Encourage the development of different forms of secondary education,

including general and vocational education, make them available and accessible

to every child, and take appropriate measures such as the introduction of free

education and offering financial assistance in case of

need:[15]

In 1999 the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission conducted

an Inquiry into rural and remote education. The Inquiry found that there were

over 950 young people of secondary school age in East Arnhem Land without access

to secondary education.[16] While

some work has been done to provide limited secondary options in East Arnhem Land

since 1999, we simply don’t have accurate data telling us who is missing

out. We don’t know how many remote Indigenous students are being educated

in makeshift facilities with part-time visiting teachers. We don’t know

how many students live in communities across Australia with no electricity and

no educational facility.

Australia has not been a big spender on educational institutions compared

with other countries. In its 2007 publication, Education at a Glance 2007 the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) identified

that Australia has proportionally lower spending on education as a percentage of

GDP compared with New Zealand, Iceland, South Korea, Chile, and a number of

European countries.[17]

There is work ahead for governments to chart the populations of actual and

projected school-aged children by Australian statistical subdivision, and match

these populations to school and preschool infrastructure. The relative

underspending of Australian governments on education is likely to have had

impacts in remote Australia. Without data, we cannot assess these impacts.

3 Are Indigenous students in remote Australia

receiving quality education?

Article 29 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child states that:

... the education of the child shall be directed to (a) the development of

the child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to

their fullest potential ...[18]

Article 2 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child states

that:

States Parties shall respect and ensure the rights set forth in the present

Convention to each child within their jurisdiction without discrimination of any

kind, irrespective of the child’s or his or her parent’s or legal

guardian’s race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other

opinion, national, ethnic or social origin, property, disability, birth or other

status.[19]

Despite decades of educational debate and fluctuating attention on Indigenous

education, there appear to be no definitive approaches, no givens, and no

fundamental positions that bureaucracies adhere to and categorically apply when

delivering education to remote Indigenous students.

This is borne out by two facts. Firstly, new approaches are being

continuously trialled in an effort to improve the less than acceptable national

literacy and numeracy test results and secondly the various approaches have not significantly improved the academic achievements of Indigenous

students over time. Let me re-iterate that point – the evidence of the

past decades shows us that there is no one literacy approach that provides a

‘quick fix’ for remote Indigenous education.

Those people who have followed Indigenous education policy in past decades

will have witnessed a cyclic and repetitive process of ‘new’ and

favoured educational initiatives and approaches. People who have been teaching

for long enough will have noted how some approaches are promoted, then demoted,

only to re-emerge a decade later. New attendance schemes, new literacy

approaches and new curriculum frameworks are worked and reworked. Some are

funded for a short time and enthusiastically embraced by schools, only to be

de-funded at the end of a three or four year funding cycle.

Schools continue to be the experimental grounds. School personnel have had

little choice except to be compliant in the face of an ever shifting procession

of policies and an increase in compliance activity and data collection demands.

With no authoritative guide to Indigenous education and no real

‘science’ or empiricism to guide the decision-makers, at any given

time, the newly funded and favoured policy approaches are those that have been

promoted by the most powerful policy advocates. And any new Indigenous

initiative is invariably a pilot project, usually on a short Commonwealth

funding cycle with high reporting responsibilities.

There are good reasons to explain why a single, sustainable and transferable

Indigenous education approach is elusive. Education approaches are highly

influenced by the environmental context. The outcome of any approach is affected

by the quality of the school leaders and educators; the resources available to

the students; the environment in which the students are learning; and the

general health and well-being of the student.

In remote areas, the school environment is often less predictable than in

urban settings. At the school level there are the following variables:

- How well funded is the school? Do the student numbers attract at least one

full-time teacher? - What kind of books and learning materials are available? Is there internet

access? - How good is the school leadership? Are there Indigenous leaders and teachers

at the school? - Have the best and brightest teachers been recruited to the school? To what

extent are the educators competent communicators in a cross cultural

environment? - How well trained are the teachers in literacy and numeracy approaches? Are

the teachers experts in their fields? Are they even trained in the subjects that

they teach? - What is the teacher turnover? If the turnover is high, is the school

curriculum structured in a way to avoid repetition and ensure continuity of

content and complexity?

The outcome of any educational approach can also be influenced by

resources in the local community:

- What level of preschooling or early childhood learning is available and

accessible to the children in the community? - How well resourced is the community in terms of healthcare services,

housing, policing and access to affordable, nutritious food? - Is this influencing the health and the learning abilities of the children?

For example, how prevalent is hearing impairment?

The governance and leadership within the community and the region

can also have a large impact on educational outcomes for students:

- Are there regional plans or community plans that tie together preschooling,

primary and secondary education and post school options like further study or

employment pathways? - Are there leaders in the community to provide role models for the students?

- To what extent is the community involved in the school and supportive of its

aims? - Is there employment or employment plans for the community and beyond so that

students can see the relevance of learning and a life after school?

The many and complex variables that impact on school education mean

that it is quite difficult to assess educational approaches. Each school and

each community is unique with its own strengths and challenges. Therefore, while

we can look at a whole school approach to literacy for example, and know that it

may have some impact on the students’ learning of literacy, we know also

that there are numerous other variables at work. We know that the approach will

be influenced by the expertise of the teacher and the functioning of the

community. We know that just getting the child to school is a factor.

All of this gives us some important information. It tells us that any

educational approach is only part of the equation. There are numerous variables

and a one-size-fits-all approach will not achieve the same results in different

environments.

Yet there is a problem here. Departments of education do not operate in a way

which provides a school-by-school approach to resource allocation. While there

may be some provision for local requirements, departments are usually reliant on

formulas that drive staffing allocations and school resource allocations.

Some supplementary Commonwealth Indigenous Education Program (IEP) funding is

available for schools through an application process. For example, the

Indigenous Education Projects - Capital and Non-Capital Project funding is

available to schools that can demonstrate projects which advance the objectives

of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Policy (AEP).

Schools must present their case to be eligible for these funds. However, small

remote schools are often under-resourced in terms of people and expertise and

therefore can be limited in their ability to advocate for these funds. In fact

the remote schools with the greatest infrastructure needs are often least able

to access capital funds.

A remote school with two to three teachers will be pressed to deliver the

curriculum program alone, and unable to dedicate resources for local advocacy.

In fact it is usually the successful schools and the loud advocates that attract

government funds and resources.

Success can often bring additional resources and disadvantage can often breed

further disadvantage.

Schools perform poorly because they may be under-resourced and remote from

support services. In turn, education departments question the performance and

the viability of underperforming schools. Departments may be under pressure for

results from Commonwealth funders and state or territory Ministers and

underperforming schools become a problem to be solved rather than a problem to

be resourced.

Underperforming schools are usually the small remote schools with high

proportions of Indigenous students who do not speak English as their first

language. It is these schools and these students who become the subjects of the

‘mainstream education’ versus ‘education in the

community’ debates.

While I have said that there are no agreed givens governing Indigenous

education approaches, implicit in the questions I ask in this

introduction are assumptions about the fundamentals that are required for a

sound educational environment and service.

4 Indigenous education policy

There are some consistent themes in national Indigenous education policies.

One theme that has been given considerable emphasis is the requirement for

schools to form partnerships for decision-making with Indigenous communities.

The first goal of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education

Policy (AEP) provides clear direction for Indigenous involvement in education

decision-making.

Major Goal 1 - Involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People in

Educational Decision-MakingMajor Goal 2 – Equality of Access to Education Services

Major Goal 3 – Equity of Educational Participation

Major Goal 4 – Equitable and Appropriate Educational

Outcomes.[20]

The Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth

Affair’s (MCEETYA) policy Australian Directions in Indigenous Education

2005 – 2008 also provides logical direction for Indigenous education

including partnerships in decision-making. It outlines five policy domains for

Indigenous education:

- Early childhood education

- School and community educational partnerships

- School leadership

- Quality teaching

- Pathways to training, employment and higher

education[21]

What strikes me immediately about the five MCEETYA domains is that

they are no different to educational priorities for mainstream education. The

domains outline the fundamental requirements for a coherent education service,

no matter what the skin colour of the child. However, these five domains are

especially critical for remote Indigenous education because they describe areas

of provision that are absent in most remote and some regional locations.

The difficulty with the national policies is that while some Indigenous

specific funding is tied to them, it is the states and territories that have

responsibility for implementing education policy at the school level. The

Commonwealth and state divide is a large obstacle to the implementation of

coherent education policy. It is here that we hope to see cooperative federalism

at its best, but unfortunately the Indigenous education systems have become

complex, overly bureaucratic and unfocussed.

The unfortunate outcome of the federal, state systems is that good policy

goes unimplemented. In the case of the MCEETYA recommendations there is an Enabling process to give effect to the five domains. However the Enabling process is a reporting and monitoring mechanism and not an

implementation guide. Because the Commonwealth Parliament does not have

legislative powers over state school education systems, there are limits on its

ability to enact its policies. A body like MCEETYA can mandate reporting

obligations to COAG, but it cannot hammer out an implementation strategy that

ensures its five domains are implemented at the school level.

While this chapter is not structured around the MCEETYA domains or the goals

of the AEP, my aim is to provide some recommendations for their implementation.

The first part of this chapter focuses on School and community educational

partnerships, as this is the most critical domain, and its success can lead

to the realisation of all other domains.

I support the direction of the MCEETYA policy and the National Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Education Policy. With a new federal government and new

opportunities for Commonwealth and state collaboration, much can be achieved if

remote communities are resourced to develop:

- Local education forums which promote a shared understanding between

students, their guardians and school staff about what education seeks to

achieve; - Functioning community governance structures to advocate and coordinate

education resources at the local level; - Indigenous school leadership and Indigenous educators;

- Top quality teachers and school leaders;

- Excellent preschool, primary and secondary school infrastructure; and

- Pre and post school options.

Part 3: School and community

partnerships

To a large extent, school and community education partnerships are a

‘given’ in urban settings. Parents and communities make relatively

well informed assumptions that schools reflect their values and aspirations. In

fact parents often select a school based on their value systems, religion or

philosophies. For the most part, education in urban environments is tailored to

the kinds of outcomes that parents know and expect. For example, urban parents

know that school is partly a preparation and a pathway to tertiary education or

employment. For this reason, urban parents make a relatively well informed

assumption that the school operates in partnership with them, reflecting their

expectations and their values.

In remote communities many of the resources and options we take for granted

in urban communities simply don’t exist. Pre and post-school options are

often limited or non-existent and there is likely to be limited employment in

the region. Parents may have different views about what they want their children

to achieve from education, and some may question the point of formal education

if there are limited employments choices in the region. The non-Indigenous

school staff and community members most probably have different cultural values,

aspirations and life experiences. In fact, the points of difference may be

greater than the similarities.

Despite these significant differences, the remote school model is likely to

resemble its urban school counterparts and share a similar program and

curriculum. With different languages, religions, philosophies and value systems,

it is easy to see why some remote Indigenous parents and carers stay away from

the school and do not feel part of its culture.

Yet it is these very differences that make school and community partnerships

a necessity for successful schooling in remote regions. Evidence tells us that

education is most likely to be successful when there are congruent messages

being delivered by parents and by the school. A disjunction between the two

groups only creates confusion and mixed messages for

learners.[22]

Parents, carers, students and education providers must have a shared

understanding about the purpose of school - what it provides, and what all

parties can reasonably expect. The aspirations of parents and teachers must be

discussed so that there is common understanding about the focus of the school

program.

School staff need to explain the curriculum requirements, including any

constraints on the ways in which they provide an educational service. Pre and

post schooling provide the context and the bigger picture for education over the

life cycle and should be part of local discussions. Post school options are an

especially critical part of any discussion between parents and schools because

they shape some of the purpose of schooling.

The education debates should occur in these forums – not at a distance.

It is the parents, the elders, the students and the wider community who should

decide the education approach. Do parents want their children in boarding

schools for senior secondary education? Does the community want the school to

provide Bilingual education? What is the best approach to suit the local

needs?

Local negotiations and agreements are the only way to shape the provision of

education in remote communities because of the inherent complexity and diversity

of each community. In addition, we know that it is not possible for education

bureaucracies to be education providers at a distance. They simply can’t

do it in a way which is responsive to local needs and aspirations. The tiers of

state and federal government further complicate education provision and

coherence.

The funding and administration of Indigenous education is particularly

complex and there is a good deal of duplication of effort.

The Commonwealth and the states both develop education policies and

initiatives to support the coordination and implementation of Indigenous

education. The Commonwealth provides significant supplementary funding for

Indigenous education in primary and secondary schools and financial support for

Indigenous families of primary and secondary

students.[23] The Commonwealth does

not have direct control of education provision to Indigenous education however,

unless its funding arrangements are through Tied

Grants.[24]

It is the state and territory departments that recruit and employ teachers,

fund and maintain school infrastructure and develop the curriculum frameworks

which drive the classroom content. Australia’s states and territories have

their own legislations governing primary and secondary education and they also

regulate and administer financial support to the non-government school

sector.

As well as the government and non-government education providers, there are

philanthropic organisations and others who add a further layer of complexity to

the administrative arrangements for school education. This means that Indigenous

education funding and policies are not always coherent. It also means that we

cannot assign responsibility for Indigenous education to one tier of government

nor can we assign the implementation of Indigenous education to a single

provider group. We must therefore consider the process of delivering remote

Indigenous education as a coalition effort with numerous forces and interests.

1 The state cannot do it on its own and neither can

remote communities

Decisions about educational approaches and resources must be made at the

community level and bureaucracies must be in a position to respond to

requirements on a community-by-community basis. The capabilities of centralised

bureaucracies to design and deliver services to remote regions are approximate

at best.

The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) trials of 2003 to 2005 were an

attempt to coordinate services to Indigenous communities from the different

tiers and departments of Australian governments. The COAG trial outcomes and

evaluation at Wadeye in the Northern Territory should be instructive for

policy-makers attempting to coordinate services for remote Indigenous

communities.

The trial failed due to the intractability of government departments. The

whole-of-government approach relied on coordination from centralised

bureaucracies rather than from the community. According to an independent

evaluation of the Wadeye trial, bureaucracies were primarily interested in

defining their turf and their responsibilities and neither the Commonwealth nor

the Northern Territory governments acted upon community

requests.[25]

Community proposals for action were considered to be draft documents with an

unclear status. Even though the Wadeye community had developed a representative

governance model to give voice to the 20 clans in the Thamarrurr region, the

representative voices of the local people were not heeded.

Ultimately the trial demonstrated the inability of governments and their

departments and agencies to participate in cooperative federalism when they must

share responsibility for service delivery. It demonstrated that governments lack

the capacity to be responsive to decentralised communities with diverse needs.

Over the three year period of the trial four new houses were built. This

occurred at a time when 15 houses became uninhabitable and 200 babies were born

into the community - a community which already had overcrowding. While some

additional funds were provided as part of the Wadeye trial, the reporting

responsibilities increased

exponentially.[26]

Most government services are designed for urban requirements and adapted for

remote and regional contexts. Such a limited model cannot meet the needs of

communities that are different in composition, demography and resources from

urban communities. The administration of services must be driven from the

community so that there is a direct connection between what is required and what

is delivered.

The findings of the Wadeye evaluation support MCEETYA’s School and

community educational partnerships model. They are:

- Expectations of the partners need to be clarified and mutually understood at

the outset and reviewed periodically throughout the process. - The identification of priorities needs to be specific, mutually understood

and limited to an achievable level. - Shared Responsibility Agreements should encourage the development of

achievable deliverables that result in visible outcomes on the ground. - The processes require a discipline on the part of the partners if they are

to be effectively implemented. - There is a need for an ‘authorised’ person (or group) to manage

the process on behalf of the partnership. Someone (or some body) needs to be in

charge of the trial. - There is a need to work within the capacity of the Council and the community

when developing strategies for delivering services. - Developing effective communication links between the partners and within

agencies is essential for the whole-of-government approach to

succeed.[27]

Establishing the need for partnerships is something that is

relatively easy to come to in principle. It is considerably more difficult to

develop the structures which make partnerships functional and self sustaining.

An effective vehicle to do this might be through local education forums.

However, if local education forums are to be established in future, they will

require funds to pay a secretariat to communicate and record their

recommendations and agreements. Local forums may also require funding for

associated services such as translator/ interpreter services where required.

Each local forum must be able to communicate with relevant education providers,

government departments, industry groups, philanthropic groups and non-government

organisations.

Funding arrangements for parental involvement in school decision-making have

changed in the past decade and there is evidence that funds for this purpose

have diminished. The Aboriginal Student Support and Parent Awareness (ASSPA)

program operated until 2004. The ASSPA programs were developed to:

- increase the participation in education and attendance of Indigenous youth

of compulsory school age; - encourage the establishment of effective arrangements at the local level for

the participation of Indigenous parents and community members in decisions

regarding the delivery of preschool, primary and secondary educational services

to their children; - promote increased awareness and involvement of Indigenous parents in the

education of their children; - develop the responsiveness of schools and their staff to the educational

needs and aspirations of Indigenous students; - encourage the participation and attendance of Indigenous children in

preschool education programmes; and - achieve the adequate preparation of Indigenous children through preschool

education for their future education.

The ASSPA funding was allocated to each school committee based on a

per capita formula taking into account the number of Indigenous students

enrolled at the school and whether the students are preschool/ primary or

secondary, weighted for remoteness. The per capita rates were:

Primary/preschool remote $215

Primary/preschool non-remote $110

Secondary remote $315

Secondary non-remote $160[28]

ASSPA was replaced in 2005 by the Parent School Partnership Initiative (PSPI)

program.

The new PSPI funding is obtained through a submission process which puts the

onus on the school to apply for funds. The Australian Education Union conducted

a survey in 2005 to determine the impact of the changes. Of the 561 responses,

116 replies indicated ‘that the submission writing process [was] too

difficult.... Many schools have determined that the small amount of funding

[was] not worth the effort and have not applied.’ In 2004, 430 of the 561

respondent schools (77 percent) had ASSPA committees receiving a total of

$2,529,325. In 2005, 53 of the 561 schools (9 percent) received funding for the

Parent School Partnership Initiative (PSPI) at a total amount of

$600,431.[29] While the AEU survey

was limited to respondent schools, there is evidence that the PSPI funding is

not meeting its targets Australia-wide.

The PSPI is part of the Government’s Whole of School Intervention

Strategy which aims to involve communities and parents in schools. The Whole of

School Intervention Strategy comprises two elements:

- the Parent School Partnerships Initiative which aims to improve attendance,

literacy and numeracy skills and Year 12 educational outcomes; and - Homework Centres (HWCs) which provide a supervised after school hours

environment for Indigenous students to complete their homework and to study.

In 2006 more than $32 million was approved for distribution for the

Whole of School Intervention Strategy. However the expenditure was less than the

amount approved and only $26,451,270 was

distributed.[30] The underspend may

have occurred because small, remote schools had difficulty with the submission

process. Given that 50 percent of PSPI funding is targeted to remote schools, it

would be useful to see a disaggregation of these funds to see whether remote

schools were able to take up their 50 percent

allocation.[31]

Making partnerships work in future will require the development of capacity

at the local or regional levels. Rather than putting the onus on schools to

develop submissions as is the case for PSPI funding, governments should ensure

that communities or regions are resourced to create capacity for these forums.

This may mean providing additional resources in places where there are limited

governance structures or where the capacity of the local community is limited.

The Australian Government along with state and territory governments will need

to make a commitment to education partnerships if these bodies are to be

established in future.

The commitment must be more than Commonwealth policy. The commitment in

policy must be accompanied by a facilitating process and funding which enables

implementation. At this stage the Parent School Partnership Initiative program

is not adequately targeted for its purposes. This program is not going to assist

small remote schools because of the onus it puts on schools to apply for funds

and report the expenditure. The application and reporting obligations put small

remote schools at a disproportionate disadvantage. Therefore governments must

develop new funding and resourcing arrangements to realise this policy

objective.

The Close the Gap coalition has developed agreement models with

targets and benchmarks which hold the tiers of government accountable for

implementation actions as well as health equality outcomes. The National

Indigenous Reform Agreement is the overarching framework for the Close

the Gap agreements. It captures the objectives, outcomes, outputs,

performance measures and benchmarks that all governments have committed to in

order to close the gap in Indigenous health disadvantage. It is a guiding,

monitoring and evaluation framework which could be replicated for the purposes

of monitoring and evaluating government action on remote Indigenous education.

Performance against the measures of the National Indigenous Reform

Agreement will be reported by the Steering Committee for the Review of

Government Service Provision in the report to COAG, Overcoming Indigenous

Disadvantage. Similar reporting could be made on remote education. It is

essential that we see national reporting to assess action against targets and

consistency across jurisdictions.

2 How do we form education partnerships?

The Deputy Chief Minister of the Northern Territory recognises the importance

of remote education partnerships and is in the process of developing Community Partnership Education

Boards.[32] The Minister said

the following about the role of the Community Partnership Education Boards:

These structures must allow communities to assume more responsibility and

accountability for the delivery of quality education and training services by

empowering them to coordinate the effective use of resources and expertise. The

new approaches to partnerships must allow groups of Indigenous communities to

form regional governance structures that can act as consumer representative fund

holders with responsibility for purchasing education and training services for

their communities.[33]

Numerous players can be a positive force in any collaboration. The challenge

is to gather them together so that there is meaningful discussion,

collaboration, information-sharing and decision-making.

There are existing models of educational collaboration that provide some

instructive frameworks for partnership approaches. In 1997 a group of people

inspired by Graham (Polly) Farmer set up a Foundation to establish and manage

after-school education support projects for Indigenous students who want to

complete their secondary

education.[34] The Foundation now

coordinates a number of projects, each tailored to suit a remote Indigenous

community. The community members and the local context are essential drivers of

each project.

The work of the Graham (Polly) Farmer Foundation is based on a coordinated

model of community development. The Foundation coordinates the actions of all

other parties and provides a central point for funding from private donors,

governments, community interests and other stakeholders. The Foundation has

developed a model for managing the projects which includes a steering committee

of project partners who have responsibility to set the strategic direction.

Case Study 1 – Graham (Polly) Farmer

Foundation: A partnership model for remote communities

- To provide support to Indigenous youth to achieve their potential.

- To enhance the skills and potential of young Indigenous people.

- To generate positive aspirations in young Indigenous people.

- To assist Indigenous youth to relate to the community in general,

particularly to other young Australians.

The Foundation establishes and manages after school educational

support projects for Indigenous students who have the capacity, interest and

potential to go on and complete their secondary education. The expectation of

the Foundation is that the students will go on to tertiary studies - university,

TAFE, apprenticeships and traineeships and employment. The projects are

individually funded through private industry, federal and state Government

support.

The ‘Partnership for Success’ projects are the central element

of The Graham (Polly) Farmer Foundation. Each Foundation project involves local

Indigenous communities, private and government partners and the Foundation

working together in partnership to introduce and manage projects to improve the

educational outcomes of Indigenous students. The partnerships aims are to enable

students to compete effectively for employment, apprenticeships, traineeships

and/ or tertiary entrance when they leave school.

Whilst each project is tailored to meet its community’s particular

needs, there are some key elements of all projects:

- Each project is a partnership between the Aboriginal community, private

industry, state and federal governments, and local schools. - The governing body for each project is a Steering Committee which is made up

of each of the project partners. The Steering Committee oversees the project and

provides strategic level management. - The Graham (Polly) Farmer Foundation establishes, facilitates and manages

the projects on behalf of the local Steering Committee. - A project leader undertakes the day-to-day organisation of the project under

the guidance of a local operations committee. He/ she is directly responsible to

the Steering Committee. - Each project develops its own vision and objectives and establishes a

process for selecting students for the project. Students are selected on the

basis of their interest, capacity and potential to succeed and complete their

secondary education. - Each project has an enrichment centre that is available to students four

afternoons a week and is used for visiting speakers and family events. The

project provides an after school environment where students receive tutoring and

support. - Each participating student and his/ her parent/ guardian sign a compact

which sets out the student’s responsibilities in areas such as school and

enrichment centre attendance, commitment to achieve and participation in project

activities. - Each project involves students being provided with intensive and targeted

support through:

- tutorial and vocational education assistance;

- access to tertiary motivational programs; and

- a progressive and comprehensive leadership and study skill program

from Year 8 to Year 12.

The Graham (Polly) Farmer Foundation ‘Partnership

for Success’ Projects are being offered in: Alice Springs; Carnarvon;

Kalgoorlie; Karratha / Roebourne; Kununurra; Mandurah; Newman; Port Augusta;

Port Hedland; and Tom Price.

3 What is success in remote education?

Essential to the success of any education system is dialogue between the

education providers (the school staff), and education consumers (the students,

parents and carers), about what education seeks to achieve. Local education

stakeholders should be in a position to discuss and consider the following:

What is school success and how does the education system give students

optimum opportunities to achieve success?

The answers to this question should form the basis of local education

priorities and plans. While not an exact paraphrase, the question is a variation

of this one - education for what? Students, parents, carers, school staff,

communities and governments need to know about the options for students both in

their region and in the wider Australian society.

In Australia, English literacy and numeracy are non-negotiable components of

education curricula. There is general agreement amongst Indigenous and

non-Indigenous education stakeholders that English literacy and numeracy

outcomes are fundamental for Indigenous and non-Indigenous students alike. Along

with other Australian students, Indigenous students sit national (English)

literacy and numeracy tests and their results are compared against benchmark

standards.

It is the other aspects of education, outside of the compulsory curricula

offerings, that should form the basis of local discussions about the shape of

local education. If education stakeholders begin by describing what success

looks like for local students, and describe success for school graduates, they

are in a position to design an appropriate education service.

At a certain point, school education becomes closely linked to post school

options. Students and their families begin to consider further training,

education or employment. Schools have a role to play in making the links to the

post school phase. The following case study shows what is possible in linking

school education to employment options in the local area.

Case Study 2 – Maningrida School: Education

and training with a focus on achieving success in the region

Maningrida is a remote coastal community in Arnhem Land, 350kms from

Darwin. It is situated on the East Bank of the Liverpool River Estuary at one of

the northern-most points of Australia. Maningrida is home to the Gunibidji

people and has a population of approximately 2,600 people; the majority of whom

are Indigenous. There are 10 Indigenous languages spoken in the region and most

residents are able to speak three or four dialects.

The local Maningrida Community Education Centre (CEC) offers primary and

secondary education to the township and the outstation communities. The CEC

provides out-reach education services and wet season education programs for the

35 Maningrida outstation communities. The CEC is a Bilingual school, meaning

that primary students learn in their own language before English is gradually

introduced during the primary years. The two languages that form the two

Bilingual programs are Ndjebbana and Burarra.

In 2003 the Maningrida (CEC) was accredited to offer secondary schooling to

Year 12. This means that students are now able to complete their senior years of

school without having to relocate to finish school.

Despite setbacks such as a damaging cyclone in 2006, the CEC has developed

a reputation for providing successful secondary school programs. Two standout

programs are the Contemporary Issues and Sciences course and the Junior Rangers course.

The Contemporary Issues and Sciences course is a formal education

program based on science, culture and caring for country. The program had its

beginnings in 2005 when local teachers and students took to the outdoors because

they did not have a science laboratory. They hoped to be able to identify

spiders and other insects in the bush environment. Since the program began in

2005, the students at Maningrida CEC have identified 45 new insect species. This

program is an excellent example of curricula which engages students by providing

an intersection between Indigenous and non-Indigenous systems of knowledge and

culture. The students use their local knowledge of flora and fauna to support

their technical learning in the classroom.

Courses such as this one are innovative in their methodology because they

engage Indigenous students in learning that is ‘hands on’ rather

than strictly classroom-based. Linking life in the Maningrida community to the

broader scientific community is an important way of recognising the value of

Indigenous knowledge and a means of creating connections outside the community.

The Junior Rangers program is integrated into the curriculum of Year 11 at

the school, offering a pathway to employment in a growth industry in the Arnhem

region. The course links to the Djelk Rangers Program which includes a

Men’s and Women’s Program as well as the Junior Ranger Program. The

Djelk Rangers Program operates under the auspice of the Bawinanga Aboriginal

Council; the entity with responsibility to manage both the land and sea country

of the Maningrida area.

Since the introduction of the science and ranger courses there have been

improvements in school attendance and academic performance. The benefits of the

programs are also being felt beyond the school gates with a number of students

accessing local employment and some going on to university education.

Since the secondary program commenced in 2003, the school has ranked highly

amongst Northern Territory schools. The number of students completing the

Northern Territory Certificate of Education has been increasing every year.

There were four Year 12 graduates in 2004, eight in 2005 and eleven in 2006,

with three students gaining entrance into tertiary institutions. Much of this

success is attributed to the fact that the local curriculum is relevant and

interesting and it reflects local requirements and opportunities in the

region.

Like the Maningrida Community Education Centre, another remote Northern

Territory community has defined its measure of education success and has worked

consistently to achieve a remarkable outcome.

The remote Indigenous community at Garrthalala in Arnhem Land decided that

they wanted the local young people to access senior secondary education in their

Homeland communities of Arnhem Land. Over a period of years, they collaborated

to develop a successful secondary education program which ultimately enabled

seven students to graduate in 2008. This is the first time that students in very

remote Homelands have been able to complete Year 12 in their communities. The

following case study tells the story of the way in which this school established

itself with very little government support. It underscores the commitment of

some very motivated people in this very remote part of Australia. It also

reminds us that there is much work ahead to provide school education to remote

Indigenous students. It tells us that when the school service is available,

incredible things can happen.

Case Study 3 – Garrthalala: Success in a

remote school

In 2008 the remote Arnhem Land community of Garrthalala had mains

electricity connected for the first time. In the same year the community

celebrated the secondary school graduation of seven local students. The students

did not go to boarding school far away from home; they were educated in their

small home communities in Arnhem Land.

It’s hard to describe the extent of this achievement. Garrthalala is

situated on Calendon Bay, one and a half hours drive over rough roads from

Yirrkala the larger Aboriginal community of the Yolngu people. To say these

homeland communities are remote is an understatement. The homeland communities

are tiny outstations, comprising a few houses that accommodate clan families

living on their ancestral lands. Some of the outstations are accessible by car,

though during the wet season they are inaccessible by road and by air.

Up until 2006 the secondary students had no classroom and had to share

space with primary school students. Power was provided by a generator. A

satellite dish provides internet access for five computers on slow dial-up

access. Students travel to the school from surrounding Homeland communities to

receive instruction at Garrthalala for three days per fortnight.

They travel by plane to this tiny school which acts as a boarding facility.

Up until 2008, those who were not from Garrthalala had to sleep on the school

floors during the night and cook their meals with assistance from teachers. In

the day time the students had to move their swags to make room for desks and

learning resources. In 2008 a small dormitory was built for cooking and

sleeping.

The secondary school building and dormitory were not provided by government

departments. They were built by volunteers from the Geelong Rotary Club of

Victoria with assistance from parents and community members of Garrthalala and

some dedicated teachers. Funds for the buildings came from the Yirrkala

Homelands School.

The school manages with no secure operational funding. The secondary

program has received some one-off funding from Commonwealth discretionary funds

and otherwise it manages with very little funding. The school receives a

staffing allocation of one lead teacher, an additional teacher and two assistant

teachers. One of the assistant teachers is a former student. There are still not

enough facilities for all of the students who want to attend the secondary

program from surrounding homelands. There will be additional challenges ahead

for this growing school.

Establishing the school and teaching the school program under these

conditions has not been an easy road. When the teachers were asked about the

difficulties of the work they said the following:

Camping out in the homelands and the heat...

At times inadequate facilities such as no air-conditioning and one shower

to share...No water at times when the solar powered pump is not working at

Garrthalala...A lack of (specialist) staffing, and staffing in general, and limited VET

courses accessible to remote students...Limited access to careers counselling for students

graduating...[35]

One can only begin to imagine the educational challenges of this student

group and its teachers. What did it need to get this school to a position where

it was able to offer Year 12? What were the resources – both material and

human? What were the preconditions and the process?

According to the school teachers, the driving force of the project

was:

the community support and support of Garrthalala elders... [It was] a

desire by Homeland communities to see secondary students access accredited

secondary education in the Homelands, away from the temptations and problems

facing Indigenous students in the hub community of Yirrkala or the mining town

Nhulunbuy.[36]

The measure of success for parents and elders was for students to complete

secondary education without having to leave their home communities. They wanted

the young people of the region to achieve the same level of education attainment

as students in urban areas. The parents, community members and students were

prepared to work hard to achieve this goal, and they did it in conjunction with

a responsive teacher workforce.

4 Developing local forums

A well functioning education system in remote locations requires a forum or a

medium through which local education stakeholders can negotiate and develop

agreements about local education priorities. Parents and education staff are

critical members of any education forum and so are councils, industry,

philanthropic groups and health providers.

Education does not exist in isolation; it is a pathway from early childhood

to employment incorporating many facets of local life such as culture, health,

safety and nutrition. Each community must be in a position to configure its own

structure which will bring together other partners at the Commonwealth and state

or territory levels.

In a Western Australian report into family violence and child abuse, Sue

Gordon and her co-authors developed a model for developing and delivering

services and channelling funding to Indigenous

communities.[37] Entitled, Planning, resource allocation and service delivery - A focus on

communities, the model provides a structure which puts local stakeholders at

the centre of decision making. The model is set out in Figure 1 below. The

benefit of this model is that it is an authoritative framework through which

bureaucracies can support and resource local plans.

While the Gordon model was developed to address family violence, the

processes for coordinated and coherent service delivery are transferrable to

other areas, including Indigenous education. Gordon argues:

There is not one piece of research that suggests that government agencies or

other service providers can deal with this [family violence] problem on their

own. It is clear from the research, consultations with Aboriginal communities,

submissions provided by government agencies and others, that Aboriginal people

and Aboriginal communities must be involved in shaping the

solutions...[38]

Figure 1: S Gordon, K Hallahan and D Henry, Model for Planning, Resource

Allocation and Service Delivery; A focus on

Communities[39]

5 Integrating industry and philanthropic groups in

education programs

There are government service providers and departments in most remote

Indigenous communities and regions. Increasingly too there are non-government

organisations or philanthropic groups delivering education programs and

facilitating community development.

Education is much more than learning in a school classroom. Learning begins

from the moment a child enters the world and continues throughout his or her

lifetime. Education occurs in the home, in the workplace, in all social settings

and during leisure time. A community and a culture that supports learning and

develops its own learning is a community that is primed for educational success.

A good education environment does not cordon off separate areas of learning;

rather it sees the different learning environments, both formal and informal, as

part of an organic whole; a whole of life education journey.

Numerous philanthropic groups, local councils and industry groups support

Indigenous community members to develop and deliver learning projects which may

be tied in with school curricula or complimentary to school programs.

In the Kimberley region of Western Australia, elders and community members

have developed projects to connect young people to country. These projects,

which sit outside of the formal education system, provide an example of the ways

in which culture, learning and employment can be driven by the community. This

form of learning should be considered in any local or regional education plan.

While the school is not always the site for learning projects, connections

should be made through local or regional plans to create potential for

collaboration and integration of the widest range of learning resources and

pathways.

The Yiriman Youth Project in the Kimberley, Western Australia is a

development and coordination point for cultural education and training projects

for young people in the region. Projects such as this one reinforce the various

ways in which education has direct meaning to the lives of young people.

Case Study 4 – Yiriman back to country project: Community education

delivered by elders and community members

The Yiriman Youth Project is an Aboriginal young men’s and young

women’s project in the Nyikina, Mangala, Walmajarri and Karajarri language

regions. This country extends from Bidyadanga in the West Kimberley to Balgo in

the Southern Kimberley.

Yiriman activities incorporate back to country trips and projects that

focus on youth at risk. The Yiriman Youth Project’s main focus is building

confidence through culture, working alongside young men and women aged between

14 - 30 years.

The project was initiated by Aboriginal elders who were concerned that some

of their young people had no jobs and no future. Elders from the four language

groups developed ideas over many years about ways they could stop substance

misuse, self-harm and suicide in their communities.

Their ideas provided the foundation for the Yiriman Youth Project which

promotes life skills and sustainable livelihoods through youth leadership, land

management and community development. All Yiriman projects have a cultural focus

aimed at developing opportunities for young Aboriginal people. The various

Yiriman activities have been successful in getting youth out of urban areas and

away from substance abuse and back onto traditional country.

Yiriman works in partnership with Indigenous organisations in the Kimberley

area. The partner organisations are many and varied. The Land and Sea Unit of

the Kimberley Land Council provides opportunities for young people to

participate in land and sea management. Mangkaja Arts and Derby Aboriginal

Health Service provide community driven bush medicine trips. The Departments of

Justice and Community Development offer diversionary programs which include

camel walks and cultural youth exchanges with the Shire of Derby West Kimberley.

Other partner organisations involved in cultural land management,

performing arts and cultural workshops include the Kimberley Language Resource

Centre, NAILSMA, the Kimberley Regional Fire Management Project, the Natural

Heritage Fund, the Australian Quarantine Inspection Service, Macquarie and

Murdoch Universities.

Passing on cultural knowledge from generation to generation has been

essential for Kimberley clans in proving their Native Title claims to

traditional lands.

Mervyn Mulardy, the Karajarri Chairperson and Yiriman Cultural Advisor

described the importance of the Yiriman Youth Project to Native Title in these

terms:

Karajarri people had to show the Federal Court their relationship to

country. Well...we gotta show our young people our connection. Take them out,

show them country and get them to look after country.The ‘Yiriman’ tower (Mesa - a small flattop hill) is one of

many very important cultural landmarks in the region.

John Watson, a Nyikina/ Mangala Elder and Yiriman Founding Director

said:

We want to show them their base (homelands). If we don’t show them

country and identity...you’re nothing! A lot of people travelled through

this countryside, it was a sign for helping people find jila

(waterholes).Yiriman is a place that a lot of people got taken away

from........we gotta take these kids back.

Anthony Watson, a Nyikina/ Mangala Cultural Advisor and Yiriman Director

said:

We want to make it known to young people that this is where their family

lived and hunted around that country. Show them where their grandfather and

grandmother were born, what they ate and how to look after country and animals.

6 Summary of issues: School and community

partnerships

- Parents, carers, students and education providers must have a shared

understanding about the purpose of school and what constitutes educational

success; - Local negotiations and agreements are the only way to shape the provision of

education in remote communities because of the inherent complexity and diversity

of each community; - A well functioning education system in remote locations requires a forum or

a medium through which local education stakeholders can negotiate and develop

agreements about local education priorities - Remote education forums will require ongoing capacity-building, resources

and funding; - The National Indigenous Reform Agreement provides a model for

assessing government action on remote education; and - Government performance on remote education should be reported by

jurisdiction to COAG.

Part 4: The best and brightest teachers and

leaders

We recognize that no education system can rise above the quality of its

teachers, as they are key to improving the quality of education as well as to

expanding access and equity.[40]

In 2007, an international study of student performance from 57 countries

found that the quality of school teachers is the most important factor

impacting on student learning outcomes. The report based its findings on data

from the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment finding that the world’s best performing school systems require three

attributes:

- Getting the right people to become teachers;

- Developing them into effective instructors; and

- Ensuring that the system is able to deliver the best possible instruction

for every child.[41]

Closer to home, a 2006 trial conducted in the remote Western

Australian community of Halls Creek demonstrated the importance of teachers in

student school attendance.[42] The

project trialled a number of strategies to increase student attendance. A

significant finding of the trial was that student attendance rates varied

between classes. One teacher had 20 percent greater attendance than other

teachers who were participating in the trial. The report found that:

‘Variations in teacher quality could well be an issue affecting school

attendance rates.’[43]

The evidence of recent decades is unequivocal; teachers play a crucial role

in the learning environment, affecting both student attendance and student

academic performance. It therefore follows that the recruitment and retention of

the best quality teachers must be of the highest priority for education

providers.

Teacher recruitment in Australia is carried out by state and territory

government and non-government education departments. Departments make varying

efforts to provide appropriately qualified people to schools within their

jurisdiction. All departments have provisions to enhance teacher recruitment to

regional and remote locations and the majority of departments have some form of

provision to encourage the recruitment of Indigenous teachers. However, the

forms of the incentives vary from provider to provider as does the quality and

focus of the various provisions.

1 Indigenous leaders and educators

The recruitment and retention of Indigenous teachers is a necessary challenge

for education systems because they show Indigenous students that school is

relevant and reflective of their world.

For the most part, our education system does not reflect Indigenous culture.

Its values and knowledge systems predominantly reinforce western cultural

perspectives and western methods of learning. Australian schools follow a

Christian calendar year and English is almost exclusively the language of

instruction in classrooms. When these value systems are foreign to the beginning

student, they can have a negative impact on the ways in which Indigenous

students see themselves as learners.

...western cultural signs have both a subtle and profound impact on students.

They help to shape each student’s view of the world, and his or her place

in it.[44]

When students are able to make associations between the information they

receive at school and at home they are able to integrate and scaffold new

learning. An Australian research project involving over 80 school sites found

that there are certain influences that improve learning outcomes for Indigenous

students. The first finding of the study is ‘...the recognition,

acknowledgement and support of

culture.’[45]

While Indigenous culture can be supported through appropriate curricula and

the placement of Indigenous art, images and symbols in the school environment,

Indigenous staff are the most important component.

International human rights standards support the right of the child to

culture.

Article 29, the Convention on the Rights of the Child states:

... the education of the child shall be directed to (c) the development of

respect for the child’s parents, his or her own cultural identity,

language and values, for the national values of the country in which the child

is living, the country from which he or she may originate and for civilizations

different from his or her own

...[46]

Article 14 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that:

- Indigenous peoples have the right to establish and control their educational

systems and institutions providing education in their own languages, in a manner

appropriate to their cultural methods of teaching and learning. - Indigenous individuals, particularly children, have the right to all levels

and forms of education of the State without discrimination. - States shall, in conjunction with indigenous peoples, take effective

measures, in order for indigenous individuals, particularly children, including

those living outside their communities, to have access, when possible, to an

education in their own culture and provided in their own

language.[47]

Indigenous leaders, teachers and role models are in short supply in

schools across Australia.[48] In

2006, Indigenous teachers with qualifications constituted only 1 percent of

teaching staff in all government schools. In Catholic schools they were 0.2

percent.[49] This is not

representative of Indigenous people as we are now 2.5 percent of the Australian

population.

The state and territory ratios tell a more compelling story. In the Northern

Territory, Indigenous people make up over 30 percent of the population while

Indigenous teachers represent 3.6 percent of the registered teacher

workforce.[50]

The continuing supply of Indigenous teachers is dependent on education

graduates. In the period from 2001 to 2006, the number of Indigenous students

commencing tertiary study

declined.[51] We now have a current

problem of short supply and a future problem with fewer Indigenous graduates

moving into schools.

As a field of study, education rates second in the choices made by enrolled

Indigenous students, For example, in 2006 the top three fields of study for

Indigenous students were as follows: 3,028 enrolments in society and culture

courses, 1,887 in education courses and 1,430 in health

courses.[52] Despite its relative

popularity, more needs to be done to increase the supply of teacher graduates to

keep pace with the growing Indigenous population.

There are systemic impediments at the national level which have impacted on

Indigenous enrolments in higher education. According to the Indigenous Higher

Education Advisory Council, the changes to income support (ABSTUDY) in 2000 had

a negative impact on Indigenous commencements:

Changes to ABSTUDY with the aim of aligning the means tests and payment rates

with those of Youth Allowance and Newstart took effect from 1 January 2000.

There was a sharp decline in higher education Indigenous enrolments in 2000 and

ABSTUDY recipient numbers in higher education declined significantly in 2002 and