HREOC Social Justice Report 2002: Measuring Indigenous disadvantage

Social Justice Report 2002

Chapter

4: Measuring Indigenous disadvantage

Part 1: Benchmarking

Indigenous disadvantage from a human rights perspectivea)

Indigenous disadvantage

b) The recommendations of the Council for Aboriginal

Reconciliation

c) The Social Justice Reports for 2000 and 20013.

Integrating Human Rights and Development: UN experiencea)

UNDP Human Development Report 2000

b) UNDP and UHCHR Draft Guidelines on Poverty

Alleviation4.

Research relevant to benchmarking

5. The Commonwealth Grants Commission Report on Indigenous

Funding

6. Australian Bureau of Statistics

7. Initiatives at the inter-governmental level related

to benchmarking

8. The Steering Committee framework for reporting

on Indigenous disadvantage

9. Governance and capacity building

10. Developments at State and Territory levelPart 2: Incorporating

human rights into benchmarking reconciliation1)

Indigenous participation in benchmarking

2) Progressive realisation of economic, social and

cultural rights

3) Statistics

4) Building Indigenous governance and capacity building

into benchmarking

5) Discussion of the Steering Committees draft

framework for reporting on Indigenous disadvantage

Conclusion Where to from here?

On 28-29 November

2002 I convened a workshop on the topic of benchmarking reconciliation

and human rights. The purpose of the workshop was to consider current

developments in setting benchmarks, identifying performance indicators

and developing monitoring and evaluation frameworks for addressing Indigenous

disadvantage from a human rights perspective. In particular, the workshop

considered the Draft framework for reporting on Indigenous disadvantage

currently being developed by the Steering Committee for the Review

of Commonwealth/State Service Provision under the auspices of the Council

of Australian Governments (COAG), as well as a range of recent human rights

and development initiatives at the international level.

This chapter reflects

on the issues discussed during the benchmarking reconciliation workshop.

The first part of the chapter provides an overview of issues relating

to benchmarking Indigenous disadvantage from a human rights perspective,

including an overview of international standards as well as recent research

and practice in Australia. The second part then reports on the discussion

of these issues at the benchmarking workshop.[1] How

Indigenous organisations and ATSIC grapple with the Government's processes

for monitoring practical reconciliation, such as the Steering Committee

framework, will be of great importance into the future. I therefore conclude

with some preliminary suggestions as to how to advance these issues over

the coming year.

Part 1:

Benchmarking Indigenous disadvantage from a human rights perspective

1. Background

issues

a) Indigenous

disadvantage

Aboriginals and Torres

Strait Islanders are significantly disadvantaged in contemporary Australian

society. This disadvantage represents a failure to provide in full measure

the human rights to which Australian Indigenous peoples are entitled.

Colonisation, and the consequent dispossession, disruption and dislocation

have impacted heavily on the well-being of Indigenous individuals and

communities.

The extent of Indigenous

disadvantage in Australia is reflected in statistics showing significant

health problems, high unemployment, low attainment in the formal education

sector, unsatisfactory housing and infrastructure and high levels of arrest,

incarceration and deaths in custody.[2] Indigenous despair

and distress is exemplified by serious substance abuse, domestic violence,

suicide and generally significant signs of social dysfunction. There are

concerns that, in a number of key respects, the socio-economic circumstances

of Indigenous peoples, particularly in remote areas, has not only not

improved, but that it has in some respects actually worsened.[3]

Concern at the level

of Indigenous disadvantage has been noted at an international level. In

September 2000 the UN Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights

(CESCR), in its Concluding Observations on Australia's third periodic

report concerning its obligations under the International Covenant on

Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), expressed its:

deep concern that,

despite the efforts and achievements of the State party, the indigenous

populations of Australia continued to be at a comparative disadvantage

in the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights, particularly

in the field of employment, housing, health and education.[4]

However, there is

a dearth of detailed and reliable information. In 1999 Boyd Hunter observed

that:

Indigenous Australians

are the most disadvantaged and poorest sector of Australian society.

Given these circumstances, the lack of information on what is a significant

problem is surprising [T]he fragmentary and incomplete nature

of existing studies leaves policy makers without direction in attempting

to deal with entrenched indigenous poverty.[5]

The significance

of the extent of disadvantage suffered by Indigenous Australians was highlighted

by the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC) in

1991. A central finding of the final Report of the RCIADIC was that Aboriginal

people in custody did not die at a greater rate than others. [6]

Rather, the reason for the high number of Aboriginal deaths in custody

was that the Aboriginal population was over-represented in custody: 'Too

many Aboriginal people are in custody too often'. [7]

Consequently, many of the recommendations of the Report addressed the

underlying causes of this situation. The Report found that:

The single significant

contributing factor to incarceration is the disadvantaged and unequal

position of Aboriginal people in Australian society in every way, whether

socially, economically or culturally.[8]

The emphasis on the

social, economic and cultural disadvantage underlying incarceration and

deaths in custody was a defining characteristic of the Report. It linked

the symptoms of Indigenous distress, such as the high rate of encounters

with the criminal justice system, with the underlying cause of

systemic disadvantage suffered by Indigenous Australians. The RCIADIC

identified as fundamental the disempowerment and marginalisation of Indigenous

peoples. Accordingly, it identified the necessity that:

principles of self-determination

should be applied to the design and implementation of all policies and

programs affecting Aboriginal people, that there should be maximum devolution

of power to Aboriginal communities and organisations to determine their

own priorities for funding allocations, and that such organisations

should, as a matter of preference be the vehicles through which programs

are delivered.[9]

While the linkages

between Indigenous distress, socio-economic disadvantage, and the need

for self-determination, were clearly and authoritatively established in

the 1991 RCIADIC Report, progress since then in dealing with these issues

has been unsatisfactory. As ATSIC pointed out in its submission to ICESCR

in 2000: 'attempts to remedy the over-all disadvantage of Indigenous Australians

have been partial, inadequate and without clear objectives and targets'.[10]

In the context of

the movement towards reconciliation, it has become increasingly evident

that reconciliation entails more than acknowledgement of prior occupation

and ownership, expressions of apology or regret, and the granting of (limited)

native title and land rights, as important as these are. While ever the

social, cultural and economic circumstances of Indigenous Australians

remain parlous and Indigenous peoples vulnerable, social justice is lacking

and there is no firm basis for true equality, respect and co-existence.

The RCIADIC identified the need for a process of reconciliation, and in

doing so confirmed that the success of the reconciliation process would

be integrally linked with addressing Indigenous disadvantage.

b) The

recommendations of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation

On 7 December 2000,

the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation (CAR) presented to the Parliament

its final report, Australia's Challenge. [11]

The Report made six recommendations focusing on processes and accountability

in the context of reconciliation. The first of these recommended that:

The Council of

Australian Governments to agree to implement and monitor a national

framework for all governments and ATSIC to work to overcome indigenous

disadvantage through setting benchmarks that are measurable, have timelines,

are agreed with Indigenous peoples and are publicly reported.

This recommendation

reflected CAR reconciliation documents released earlier in the year, namely

the Australian Declaration Toward Reconciliation and the Roadmap

for Reconciliation. The Declaration included the pledge to

stop injustice and overcome disadvantage and the Roadmap contained

four national strategies recommending ways to transform the commitment

to reconciliation into actions. In the context of benchmarking reconciliation,

of significance is the National Strategy to Overcome Disadvantage,

focusing on education, employment, health, housing, law and justice. Guidelines

for implementing this Strategy were published as Overcoming Disadvantage

- Ways to implement the National Strategy to Overcome Disadvantage, one

of four National Strategies in the Roadmap for Reconciliation.

Overcoming Disadvantage

emphasised, as essential to holding governments accountable, the need

for reliable information about the level of need, the money spent and

the services delivered. It identified benchmarking as a means to do this.

It stressed that accountability and benchmarking required not just accurate

data, but also a measure of independence and honesty in data collection

and analysis. It further urged that territory, state and federal Governments,

and ATSIC, with respect to both mainstream and Indigenous specific programs,

set national state, territory and regional outcomes and output benchmarks,

where they do not currently exist, that are measurable, include time-lines

and are agreed in partnership with Indigenous peoples and communities.

Governments should publicly and annually present an outputs and outcomes

report to their respective parliaments, on a whole-of-government basis,

against these agreed outcomes.

The report identified

the leadership role of the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), and

the need for the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) to continue to

improve Indigenous data through the census and other surveys, and the

need for data agencies such as the ABS, the Australian Institute of Health

and Welfare, the Australian Institute of Criminology and the Steering

Committee of the Review of Commonwealth/State Service Provision to extend

their Indigenous data collections and reporting and provide more Indigenous/non-Indigenous

comparative statistics and breakdowns at the regional and sub-regional

levels.

The parameters of

the project of benchmarking reconciliation are clearly set out in these

CAR documents. CAR has come to the end of its life, and the focus of activity

has tended to shift to agencies involved in the practical issues of implementing

benchmarking programs to address Indigenous disadvantage. While the successor

to CAR, Reconciliation Australia, will retain an active interest, other

agencies and organisations have the task of following the roadmap set

out by the CAR. The roles will range from advocacy and monitoring through

to policy and planning and the technical issues of collecting and interpreting

data. Indigenous organisations and communities will need to be effective

partners in the process if it is to work and have meaning.

The Government's

response to the Council's documents, and specifically recommendation 1,

are discussed in detail in chapters 2 and 3 of the report. The initiatives

undertaken by the Council of Australian Governments in accordance with

the recommendations are discussed further below.

c) The

Social Justice Reports for 2000 and 2001

The Social Justice

Report 2000 provided a rights-based approach to progressing reconciliation.

Chapter 4 of the Report, 'Achieving meaningful reconciliation', provided

a detailed analysis of the processes and mechanisms that enable reconciliation

to be implemented within a human rights framework. In particular, five

integrated requirements were identified that need to be met to integrate

a human rights approach into redressing Indigenous disadvantage and to

provide sufficient government accountability. These five requirements

build on the CAR work, and provide a framework for addressing Indigenous

disadvantage. They are as follows.

|

Five

|

Based on these five

requirements, the Report contained fourteen detailed recommendations relating

to:

- national commitments

to overcome Indigenous disadvantage;

- improved data

collection;

- monitoring and

evaluation mechanisms;

- negotiating with

Indigenous peoples; and

- protecting human

rights.[13]

This comprehensive

set of recommendations complement those of CAR and specify the central

position of human rights for meaningful reconciliation. Together with

the CAR recommendations they provide a series of actions as a checklist

for determining progress in respect of advancing reconciliation. In respect

of the requirement concerning negotiating with Indigenous peoples, this

necessity has been identified for some time. In particular, this matter

was spelt out in the social justice package proposals put to the Government

in 1995 by ATSIC, CAR and the Social Justice Commissioner.[14]

The Social Justice

Report 2001 noted, notwithstanding COAG agreeing to a communiqué

on reconciliation in 2000 [15] which adopted the first

recommendation of CAR ( a national framework for overcoming Indigenous

disadvantage through setting benchmarks), the slow progress and lack of

specificity in responding to the Reconciliation documents. In the Government's

response to the Social Justice Report of the previous year, there had

been no mention of the fourteen recommendations in the Report and no response

to any of them. Noting that the commitments the 1992 COAG National

Commitment to improved outcomes in the delivery of programs and services

for Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders and the 1997 National

Ministerial Summit on Deaths in Custody for improved coordination of funding

and service delivery and for negotiated national benchmarks and targets

had been largely not implemented, the 2001 Report stated that: 'Government

programs and inter-governmental coordination continue to lack sufficient

accountability and transparency'.[16]

The Report noted

some positive developments at state government level, in particular the

conclusion of Justice Agreements. However, due to concerns about the lack

of response to the CAR documents, as well as the inadequate response to

the Social Justice Report 2000, the Social Justice Commissioner

made a further recommendation, calling for a Senate inquiry into national

progress towards reconciliation.[17]

On 27 August 2002,

the Senate referred to its Legal and Constitutional References Committee

an Inquiry into the Progress Towards National Reconciliation. The

Social Justice Commissioner, in welcoming the Inquiry, noted that it directly

responded to Recommendation 11 of the 2001 Social Justice Report. The

Terms of Reference require the Committee to inquire into:

- progress towards

national reconciliation, including an examination of the adequacy and

effectiveness of the Commonwealth Government's response to the reconciliation

documents cited in the Social Justice Commissioner's 2001 recommendation;

and - the adequacy

and effectiveness of any targets, benchmarks, monitoring and evaluation

mechanisms that have been put in place consistent with the reconciliation

documents.[18]

2. The

Human Rights Context

The Social Justice

Report 2000 sets out four basic human rights principles as the necessary

basis the realisation of reconciliation. They are:

- No discrimination,

that is, a guarantee of equal treatment and protection for all. Equal

protection includes recognition of distinct cultural characteristics

of particular racial groups (substantive equality), and can require

temporary special measures of assistance to overcome inequalities; - Progressive

realisation, that is the commitment of sufficient resources through

well targeted programs to ensure adequate progress in the realisation

of rights over time; - Effective

participation, that is ensuring that individuals and communities

are adequately involved in decisions that affect their well being, including

the design and delivery of programs; - Effective

remedies, that is the provision of mechanisms for redress when human

rights are violated.

These four principles

are more than a statement of objectives or goals to be met as and when

governments feel it is appropriate or practical to do so. Rather, they

are a distillation of the human rights principles and norms which make

up the international law of human rights. They are contained in various

international instruments to which Australia is party and which consequently

are binding on Australia. And while the particular application of these

norms may take account of local circumstances and the constraints that

may exist, there is no discretion as to whether these norms are to be

applied to the fullest extent possible. This is an obligation of international

law, and a nation fails to meet these obligations at the peril of its

international reputation and standing. The process of reconciliation should

be seen as part of the realisation of human rights. Thus, as the scope,

content and meaning of these rights have to a large degree been elaborated

in international forums, it is important to see reconciliation as having

both domestic application and an international dimension.

Economic, social

and cultural rights are as much a part of international human rights law

as are civil and political rights, although they have only achieved full

recognition in more recent times. They were originally asserted in the

foundational instrument of human rights law, the 1948 Universal Declaration

of Human Rights, which stated that freedom from fear and want can only

be achieved if conditions are created where everyone may enjoy their economic,

social and cultural rights, as well as their civil and political rights.

Provisions covering aspects of economic, social and cultural rights are

contained in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

1976 (ICCPR), including in particular Article 27 relating to minority

rights, and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms

of Racial Discrimination 1969 (ICERD), in particular Article 2(2) requiring

states, when circumstances so warrant, to take special and concrete measures

in the social, economic and cultural fields to ensure adequate development

and protection of certain racial groups or individuals belonging to them.

As well, the jurisprudence of the treaty body committees established to

monitor the implementation of these instruments has added to the understanding

of the meaning and scope of the relevant provisions.

The central instrument,

however, in respect of matters affecting the health and well-being of

Indigenous peoples and communities is the International Covenant on Economic,

Social and Cultural Rights 1976 (ICESCR). The work of this Covenant's

treaty body, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR),

particularly through the interpretation of its provisions by way of General

Comments, provides authoritative guidance to an appreciation of what is

involved in the obligation to seek the progressive realisation of these

rights.

Australia has ratified

ICESCR and is consequently bound to implement its provisions as they apply

to Australia. Article 2 (1) requires a State party to the Convention to

undertake:

to take steps to

the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively

the full realisation of the rights recognised in the present Covenant

by all appropriate means... (emphasis added)

This provision is

further elaborated by CESCR's General Comment 3.[19]

It is controlling in respect of all the other provisions of the Covenant.

[20] While the obligation 'to take steps' means that

the full realisation of relevant rights may be achieved progressively,

the taking of such steps cannot be delayed, and further, those steps should

be deliberate, concrete and targeted as clearly as possible towards meeting

the obligations recognised in the Covenant. [21]

Significantly, while

the periodic reports of States to the Committee should provide not only

the measures that have been taken, but also the basis on which the State

considers those steps to have been the most 'appropriate', nevertheless

'the ultimate determination as to whether all appropriate measures have

been taken remains one for the Committee to make'.[22]

That is to say, a

State cannot purport to sit in judgment on its own performance. Additionally,

although the Covenant foresees that rights will be realised over time,

or in other words progressively, there is nevertheless an obligation to

move as expeditiously and effectively as possible. [23]

General Comment 3 also notes that a minimum core obligation is incumbent

upon every State to ensure the satisfaction of, at the very least, minimum

essential levels of each of the rights. [24] This obligation

is immediate in its application.

A number of the provisions

of this Covenant are directly relevant to the disadvantage suffered by

the Indigenous peoples of Australia. These include Article 11, the right

of everyone to an adequate standard of living for themselves and their

family. This right is instructive in that it demonstrates both the obligatory

nature of the rights contained in the Covenant and the cultural flexibility

and relativity that is encapsulated in the ICESCR approach. An implication

of the right to an adequate standard of living for Australian Indigenous

peoples can be seen in respect of housing and infrastructure. In General

Comment 4, the Committee has noted that: [25]

The human right

to adequate housing, which is thus derived from the right to an adequate

standard of living, is of central importance for the enjoyment of all

economic, social and cultural rights. [26]

Noting that in particular,

the enjoyment of this right must not be subject to any form of discrimination,

the Committee nevertheless advised that the right to housing should not

be interpreted in a narrow or restrictive sense which equates it with,

for example, the shelter provided merely by having a roof over one's head

or views shelter exclusively as a commodity. Rather it should be seen

as the right to live somewhere in security, peace and dignity. The Committee

states that:

Adequate shelter

means adequate privacy, adequate space, adequate security, adequate

lighting and ventilation, adequate basic infrastructure and adequate

location with regard to work and basic facilities - all at a reasonable

cost.[27]

The relevance of

this approach to the range of circumstances of Indigenous peoples in Australia,

including encompassing cultural expectations of housing that may differ

from the mainstream, is evident. In fact, the Committee specifically addresses

what it terms 'Cultural adequacy'.

The way housing

is constructed, the building materials used and the policies supporting

these must appropriately enable the expression of cultural identity

and diversity of housing. Activity geared towards development or modernisation

in the housing sphere should ensure that the cultural dimensions of

housing are not sacrificed, and that, inter alia, modern technological

facilities, as appropriate are also ensured. [28]

This discussion is

clearly relevant to the provision of adequate and appropriate housing

for Indigenous peoples in Australia, a major area of disadvantage of Indigenous

Australians. For example, the CESCR formulation can provide a framework

for the provision of housing on outstations which both meets equality

objectives and recognises cultural diversity. Importantly, it shows that

equality goals should not be used to obstruct people's aspirations for

outcomes which are not identical to those of the mainstream society.[29]

However, it should

also be noted that there are real challenges here for the ways targets

are constructed and indicators developed to respond to a diversity of

cultural situations and aspirations. This is discussed below.

Article 12 provides

for the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standards

of physical and mental health. The Committee has elaborated the meaning,

scope and implication of this Article in a recent detailed General Comment

(no. 14).[30] Stating that '[H]ealth is a fundamental

human right indispensable for the exercise of other human rights', the

Committee noted that the right to health has been confirmed in a number

of international instruments.[31] The Committee interprets

the right to health, as contained in the Covenant, as:

an inclusive right

extending not only to timely and appropriate health care but also to

the underlying determinants of health, such as access to safe and potable

water and adequate sanitation, an adequate supply of safe food, nutrition

and housing, healthy occupational and environmental conditions, and

access to health-related education and information, including on sexual

and reproductive health. A further important aspect is the participation

of the population in all health-related decision-making at the community,

national and international levels.[32]

Of particular note

is the inclusion of a paragraph specifically relating this right to Indigenous

peoples. [33] The paragraph emphasises the need for

health services to be culturally appropriate and for full and effective

participation by Indigenous peoples. The Committee notes that in Indigenous

communities the health of the individual is often linked to the health

of the society as a whole and has a collective dimension. As with other

rights protected by the Covenant (including the right to education), there

is an emphasis on the need to develop health strategies that should identify

appropriate right to health indicators and benchmarks. The indicators

should be designed to monitor the State's obligations under Article 12.

Having identified appropriate right to health indicators, states should

set appropriate benchmarks to each indicator, for use in monitoring and

reporting.

In summary, ICESCR

provides a normative human rights framework for addressing Indigenous

disadvantage. While the Covenant provides for a realistic and flexible

approach, it does not compromise on the obligation for States to achieve

the progressive realisation of rights as effectively and expeditiously

as possible. States are required to take steps that are deliberate, concrete

and targeted. An integral part of the obligations assumed by States in

ratifying the Covenant is to develop strategies, identify indicators and

determine benchmarks.

This approach is

now an integral feature of the international human rights regime, applying

equally to economic, social and cultural rights as to other rights. But,

going beyond the prescriptive framework of the Covenant and the other

human rights treaties, the treaty bodies charged with monitoring their

implementation have undertaken the task in a manner designed to cooperate

with and assist States in achieving human rights. International instruments

such as ICESCR now represent a considerable body of experience and expertise,

built up over the last 30 years or so.

In approaching these

issues in Australia, it is unhelpful to dispute or ignore this experience.

The development of policies to address Indigenous disadvantage is best

done in full cognizance of Australia's international human rights obligations,

and within the framework for the realisation of those rights that has

been developed within the UN. The integration of human rights principles

into the design and delivery of programs and technical assistance for

poverty eradication is the next generation of the development of human

rights, and is presently under active development in the UN system.

3. Integrating

Human Rights and Development: UN experience

Over the last five

years a major goal of the UN has been to integrate human rights principles

into the whole of the Organisation's work, including the overarching development

goal of poverty eradication. These developments are reflected in:

- United Nations

Development Program (UNDP) Human Development Report 2000; [34]

and - Office of UN

High Commission on Human Rights (OHCHR)/UNDP Draft Guidelines on

Poverty Alleviation.[35]

Representing current

developments at the international level, these documents provide useful

and relevant information and merit attention in the Australian context.

The following information is intended to note some major features, but

does not purport to provide a full summary of the documents given their

detailed nature.

a) UNDP

Human Development Report 2000

The Human Development

Report 2000 had as its theme 'Human Rights and Human Development'. This

landmark publication for the UN system emphasised the mutually reinforcing

relationship between human rights and human development, and highlighted

the need for innovative thinking, strategic planning and cultivating new

partnerships in integrating human rights considerations into program formulation

and implementation.

Chapter 5 of the

Report, Using indicators for human rights accountability, examines

the importance statistical indicators as powerful tools in the struggle

for human rights. The Report argues that developing and using indicators

has become a cutting-edge area of advocacy. In this context, the Report

notes the importance of developing indicators for:

- Making better

policies and monitoring progress; - Identifying unintended

impacts of laws, policies and practices; - Identifying which

actors are having an impact on the realisation of rights; - Revealing whether

the obligations of these actors are being met; - Giving early warning

of potential violations, prompting preventative action; - Enhancing social

consensus on difficult trade-offs to be made in the face of resource

constraints; and - Exposing issues

that have been neglected or silenced.

While statistics

alone cannot measure the full dimension of rights, they can 'open the

questions behind the generalities and help reveal the broader social challenges'.

[36] They can allow human rights to be more concretely

relied upon in designing and evaluating policy. UNDP has provided a framework

for what the statistics should measure so that they adequately assess

progress in the realisation of human rights. UNDP suggests that statistics

must address the following three perspectives, simultaneously:

- An average

perspective: What is the overall progress in the country, and how

has it changed over time? - A deprivation

perspective: Who are the most deprived groups in society, disaggregated

by income; gender; region; rural or remote location; ethnic group; or

education level. How have the most deprived groups progressed over time? - An inequality

perspective: Measuring the disparity between various groups in society,

and whether these disparities have widened or narrowed over time.[37]

Benchmarking is a

useful tool for measuring whether adequate progress is being made in realising

rights. Targets may not all be achievable immediately - they may be subject

to progressive realisation. States should identify appropriate indicators,

in relation to which they should set ambitious but achievable benchmarks

(i.e. intermediate targets) corresponding to each ultimate target, so

that the rate of progress can be monitored and, if progress is slow, corrective

action taken. Thus, indicators measure progress towards both intermediate

and ultimate targets. Setting benchmarks enables government and other

parties to reach agreement about what rate of progress would be adequate.

The stronger is the basis of national dialogue, the more national commitment

there will be to the benchmark. The need for debate and widely available

public information is clear. If benchmarks are to be a tool of accountability,

not just the rhetoric of empty promises, they must be, according to UNDP:

- Specific, time

bound and verifiable; - Set with the participation

of the people whose rights are affected, to agree on what is an adequate

rate of progress and to prevent the target from being set too low; - Reassessed independently

at their target date, with accountability for performance.[38]

The UNDP Report provides

some important qualifications on the use of statistical indicators, including

benchmarks. Statistics come with strings attached. They provide great

power for clarity, but also for distortion. When based on careful research

and method, indicators help establish strong evidence, open dialogue and

increase accountability. As the following box indicates, care needs to

be taken: [39]

|

Statistical Statistical

|

The UNDP cautions

that the powerful impact of statistics creates four caveats in their use:

- Overuse:

Statistics alone cannot capture the full picture of rights and should

not be the only focus of assessment. All statistical analysis needs

to be embedded in an interpretation drawing on broader political, social

and contextual analysis. - Underuse: Data

are rarely voluntarily collected on issues that are incriminating, embarrassing

or simply ignored. Even when data are collected, they may not be made

public for many years. - Misuse:

Data collection is often biased towards institutions and formalised

reporting, towards events that occur, not events prevented or suppressed.

But lack of data does not always mean fewer occurrences. - Political

abuse:

Indicators can be manipulated for political purposes to discredit certain

countries or actors.

b)

UNDP and UHCHR Draft Guidelines on Poverty Alleviation

The most comprehensive

documentation on developing a human rights approach to poverty alleviation

to date are the draft guidelines developed jointly by the Office of the

High Commissioner for Human Rights and UNDP. In 2001 the UN Committee

on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights requested the High Commissioner

'to develop substantive guidelines for the integration of human rights

in national poverty reduction strategies'.[40] The draft

guidelines are the outcome of that request. The objective of the guidelines

is to provide practitioners involved in the design and implementation

of poverty reduction strategies with operational guidelines for the adoption

of a human rights based approach. The purpose is to focus on providing

guidelines for the use of States that are integrating human rights into

their poverty reduction strategies. In this respect they can be of relevance

to the situation in Australia.

The guidelines state

that policies and institutions for poverty reduction should be based explicitly

on the norms and values set out in the international law of human rights,

and that the human rights approach to poverty reduction is essentially

about empowerment. The most fundamental way in which empowerment occurs

is through the introduction of the concept of rights itself. Poverty reduction

then becomes more than charity, more than a moral obligation - it becomes

a legal obligation.

The guidelines note

that:

by introducing

the dimension of an international legal obligation, the human

rights perspective adds legitimacy to the demand for making poverty

reduction the primary goal of policy making.[41]

The guidelines in

effect synthesise, develop and sytematise the various approaches that

have grown up in different agencies and in various reports and documents.

In this context, the summary provided by the guidelines of the advantages

of the human rights approach provides a useful encapsulation of the rationale

of rights-based approaches to programs to reduce disadvantage, including

Indigenous disadvantage. The guidelines state that, in sum, the human

rights approach has the potential to advance the goals of poverty alleviation

in a variety of ways:

a) By urging speedy

adoption of a poverty reduction strategy, underpinned by human rights

as a matter of legal obligation;b) By broadening

the scope of poverty reduction strategies so as to address the structures

of discrimination that generate and sustain poverty;c) By urging the

expansion of civil and political rights, which can play a crucial instrumental

role in advancing the cause of poverty reduction;d) By confirming

that economic, social and cultural rights are binding international

human rights, not just programmatic aspirations;e) By adding legitimacy

to the demand for ensuring meaningful participation of the poor in decision-making

processes;f) By cautioning

against retrogression and non-fulfilment of minimum core obligations

in the name of making trade-offs; andg) By creating

and strengthening the institutions through which policy-makers can be

held accountable for their actions.[42]

The guidelines provide

a comprehensive document. They are divided into three sections. Section

I sets out basic principles, Section II identifies, for each of the rights

relevant to poverty reduction (health, housing, education etc), the major

elements of a strategy for realising that right. Section III explains

how the human rights approach can guide the monitoring and accountability

aspects of poverty reduction strategies. Because of its special significance,

accountability is singled out for discussion in a separate section.

Particular guidelines

that spell out in detail issues of accountability and, while not always

completely relevant to the Australian situation, do provide a good deal

of potentially useful information, include:

- Guideline 4:

Progressive Realisation of Human Rights: Indicators and Benchmarks;

- Guideline 16:

Principles of Monitoring and Accountability; and

- Guideline

17: Monitoring and Accountability of States.

In summary, relevant

international norms, the views of the treaty monitoring committees, and

developments in UN bodies in integrating human rights and poverty alleviation,

are crucial elements in addressing Indigenous disadvantage in Australia.[43]

4. Research

relevant to benchmarking

In Australia, there

have been significant developments in respect of developing indicators

and benchmarks. This section examines some relevant research undertaken

by the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR).

In 1998 CAEPR, in

conjunction with CAR, in discussing a benchmarking framework for service

delivery to Aboriginal Australians, noted that the historical reasons

for Indigenous disadvantage could be summarised under the following headings:

[44]

- Dispossession:

Prior to British occupation, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

'developed a mosaic of communities and groups with rich and enduring

cultures centred on an intimate relationship with the land and sea

Dispossession and dispersal have destroyed much of Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander societies [and] many Indigenous communities and

individuals have little or no stake in the economic life of the nation

other than what Governments may provide'.[45] - Exclusion

from mainstream services:

Up until the late 1960's, many Indigenous Australians were excluded

from mainstream services, creating 'a significant legacy of inequality

in areas such as education, health, housing and infrastructure'.[46] - Recent inclusion:

In combination with exclusion from services such as education, access

to welfare has 'unintentionally, and paradoxically, created poverty

traps from which it is hard to escape'.[47] - Past and inter-generational

poverty:

Low income has prevented the accumulation of capital and investment,

leading to inter-generational poverty. - Location in

rural and remote areas: A higher proportion of the Indigenous population

lives in rural and remote areas where there are few economic opportunities

and service delivery is disproport-ionately expensive. - Demography:

The large

and multi-generational nature of Indigenous households creates dependency

ratios and a higher economic burden than in non-Indigenous families.

Similarly, the Indigenous population's structure is more akin to that

of a developing nation, with population growth outstripping that of

the general Australian population, and with a young age structure.

Each of these factors

has implications in developing policy and programs to address Indigenous

disadvantage, and in identifying indicators, setting targets and providing

benchmarks. Consequently, as the CAR/CAEPR paper noted, there are:

problems of seeking

statistical equity without recognising the deep-rooted structural causes

of the low socio-economic status of Indigenous Australians and without

basing targets on accurate demographic data applying the principle

of equality and setting statistical targets must be both geographically

and culturally informed Governments need to be realistic about

what can be achieved, in light of the highly intractable nature of the

problem, and careful in their use of statistics There is a very

real danger that perceptions of continued policy and program failure

can do considerable harm to the argument for proactive government programs

to address Indigenous needs.[48]

A further difficulty,

illustrated by CAEPR research, is that of interpreting statistics relating

to program outcomes while recognising, and allowing for, the effect on

outcomes of Indigenous choice, where that choice may not be consistent

with the stated equality objectives of a policy or program. The policy

of self-determination is based on the possibility of choice, including

in respect of lifestyles.

Tim Rowse has argued

that the duality of policy aims, 'equality' and 'choice', has made program

indicators difficult to interpret. [49] That is to say,

Indigenous peoples may make certain choices that lead to lower than possible

outcomes in terms of, for example, employment and resultant income levels.

Consequently, it may be difficult to interpret results in terms of the

efficacy of programs in addressing the disadvantage caused by the effects

of historical disadvantage, structural constraints, and ongoing discrimination.

The possible conflict between self-determining choices and equity of outcomes,

as well as creating difficulties in interpreting data, clearly has implications

for policy formulation processes and establishing targets.

CAEPR evaluations

of the Hawke Government's Aboriginal Employment Development Policy (AEDP),

demonstrate some of these problems. For example, John Taylor, in a study

of geographic location and Aboriginal economic status as reflected in

the situation of outstations, concluded that, on the whole, remote location

is reflected in lower economic status. [50] He noted

a very high rate of 'unemployment' on outstations and also that outstation

residents display far less tendency to have school-based skills. The dilemma

in interpreting these outcomes is that outstations, rather than simply

reflecting poorer outcomes, could instead be seen as a locational trade-off

aimed at balancing a range of cultural, economic, social and political

considerations. In respect of education, the question was whether policy

was failing (in that outstation residents lacked schooling), or was succeeding

in that people were enabled by land tenure and welfare polices to choose

to live in outstations, even though at times these were far from jobs

and schools.

A related dilemma

was considered by Jon Altman and Diane Smith in respect of high unemployment

in remote localities - in this instance they noted that the statistical

exclusion from the ranks of the employed of people participating in subsistence

activities, and the failure to count their production as income-in-kind,

skewed employment and income results. [51] They further

noted that, paradoxically, if welfare income at outstations was classified

as CDEP wages, then residents would immediately be reclassified as employed.

They noted a further paradox that if such a reclassification occurred,

those now understood to be 'employed' would be limited to low incomes

- the AEDP goal of non-Indigenous and Indigenous income equality would

be forfeited. They concluded that:

Such a reclassification

could mean that the goal of income equality may not be appropriate in

the outstation context if people make a conscious choice to reside in

locations that are remote from mainstream economic opportunities. [52]

The issue of choice

poses problems of appropriateness and interpretation. It may be that quantitative

measures need to be supplemented by qualitative measures. This is in fact

proposed, in the context of identifying the poor, in the OHCHR/UNDP Draft

Guidelines on Poverty Alleviation (see above). In Guideline 1, it is noted

that:

Innovative mechanisms

will have to be designed - probably using a combination of quantitative

and qualitative methods - to elicit the necessary information in a cost-effective

way.

The Social Justice

Report 2000 also noted that 'the targets should be culturally appropriate'.[53]

The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation has made the point that there

is concern that some of the targets and desired outcomes may be:

Based on western

assumptions about disadvantage and that they have limited cultural relevance

to Indigenous peoples. Where this is the case, it may be unrealistic

to expect full statistical equality to be achieved with the wider community,

even in the long term. However, it would be wrong to describe as disadvantage

those specific statistical differences that arise directly from cultural

obligations and self-determination.[54]

The CAEPR body of

research is large, and a great deal of it is relevant to the issue of

benchmarking reconciliation. It is not possible to summarise this body

of research here. [55] Instead, some of the specific

issues concerning monitoring and evaluation that have emerged in the course

of CAEPR research are noted. These are:

- Disaggregation:

It has become clear in a number of contexts that national figures do

not reveal sufficient information and the averages or rates calculated

on a national basis may be misleading. Taylor has noted that the success

or failure of policy should be measured 'in a manner that reflects regional

priorities, the variability of participation in formal and informal

economies, and the restricted options in many remote locations'. [56]

Policy evaluations demand attention to the particularities of regions

and to evaluate employment outcomes the markets need to be differentiated.[57]Also noting the

need for disaggregation in some circumstances, the OHCHR/UNDP Draft

Guidelines on Poverty Alleviation note the need to specify groups

by geographic location, gender, age etc 'so that the problem of poverty

can be addressed at as disaggregated a level as possible'. [58] - Rates and size

of the base population: CAEPR researchers have pointed out that

any consideration of the rates of employment, unemployment and labour

force participation should take into account the size of the base population.

Taylor and Altman projected the rapid growth of the working age Indigenous

population.[59] Against this expansion in the base,

the task of achieving improvements in rates of employment, or even holding

the line, could be seen to be great. Taylor and Hunter observed that

it would be difficult in these circumstances to prevent Indigenous labour

force status from slipping. Indeed, they noted that:to move beyond

this, and attempt to close the gap between Indigenous and other

Australians, will require an absolute and relative expansion in

Indigenous employment that is without precedent.[60] - Definition

of poverty: Hunter has pointed out that the conceptual problems

of measuring indigenous poverty include the role of non-market work

(for example subsistence hunting and gathering), family size and composition,

relative prices and the geographic distribution of the population. As

well as income, people need access to adequate health care, housing

and justice. He argues that it is inappropriate to focus solely on income

as the measure of poverty, and that Indigenous poverty is in fact multi-faceted.

[61]Hunter, Kennedy

and Biddle note that an important issue is for researchers to ensure

that the assumptions made in measuring poverty are transparent and

can be evaluated by commentators contributing directly to the policy

debate. [62] Their paper attempts to illustrate

how the composition of the poor changes with small variations in seemingly

innocuous assumptions. The only point of agreement in the poverty

literature is that people who live in poverty must live in a state

of deprivation, a state in which their standard of living falls below

some minimum acceptable level. However, the way in which poverty has

been defined and measured provokes a multitude of questions, for example,

which is the best group among whom to assume income is shared-the

nuclear family, the extended family or the household? - Relationship

between variables: education, employment and income: Anne Daly found

that even when Aborigines were equal in education to non-Aborigines

they were less likely to have a job. [63] Gray, Hunter

and Schwab hypothesized that it is not absolute improvement in Indigenous

educational attainment that matters, but relative improvement as against

other Australians.[64]Schwab questioned

whether 'equity' in participation and outcome (with non-Indigenous

Australians) should be the aim of policy. Statistical equality was

likely to remain elusive, and could obscure important differences

of need.[65] - Problems of

defining and enumerating the Indigenous population: Without a defined

Indigenous population it is not possible to evaluate the impact, over

time, of government programs to address Indigenous disadvantage. Difficulties

with Census data have been considered by CAEPR researchers including

Gray,[66] and Taylor and Bell. [67]

Based on observations in remote and fringe communities, Martin, Morphy

and Taylor have made recommendations for changes in the special enumeration

procedures for Indigenous Australians which are part of Census procedures.[68]

5. The

Commonwealth Grants Commission Report on Indigenous Funding

In 1999 the Commonwealth

Grants Commission (CGC) was set the task of developing methods of calculating

the relative needs of Indigenous Australians in different regions for

health, housing, infrastructure, education, training and employment services,

to calculate indexes of need and compare the results with the actual distribution

of expenditure on those functions. Thus the Terms of Reference were restricted

to differences of need between groups of Indigenous people. The Report

of the Inquiry was presented to the Government in March 2001.[69]

However, many submissions to the Inquiry argued that addressing the large

gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people was more important than

redistributing existing funding.

The Report takes

a wide view of the issues involved in addressing Indigenous disadvantage,

and contains considerable information and analysis concerning Indigenous

funding issues. As the Social Justice Report 2000 noted:

Despite the limitations

imposed by the scope of the inquiry, the Commission's inquiry has been

an important one, vividly demonstrating the value of an independent

evaluative mechanism. [70]

The Report noted

that, given the entrenched levels of disadvantage experienced by Indigenous

peoples in all functional areas addressed by the Inquiry, it would have

been expected that Indigenous use of mainstream services would be at levels

greater than those of non-Indigenous Australians. However, this was found

not to be the case. Indigenous Australians in all regions access mainstream

services at very much lower rates than non-Indigenous people. The inequities

resulting from the low level of access to mainstream programs are compounded

by the high levels of disadvantage experienced by Indigenous peoples.

This also meant that specific programs for Indigenous peoples were carrying

an additional burden of compensating for the lack of access to mainstream

programs.

The Report came to

a number of conclusions and identified a range of suggestions to improve

performance, including changes to existing Commonwealth-state arrangements

by introducing and/or reinforcing additional conditions on Special Purpose

Payments (SPPs) (see below), moving to insert regional needs-based allocation

requirements into Indigenous specific SPPs; and seeking conditions on

general SPPs to direct expenditure to aspects of services that are important

to Indigenous peoples.

The Report identified

a number of important principles and key areas for action that should

guide efforts to promote a better alignment of funding with needs. These

include: [71]

(i) the full and

effective participation of Indigenous people in decisions affecting

funding distribution and service delivery;(ii) a focus on

outcomes;(iii) ensuring

a long term perspective to the design and implementation of programs

and services, thus providing a secure context for setting goals;(iv) ensuring

genuine collaborative processes with the involvement of government and

non-government funders and service deliverers, to maximise opportunities

for pooling of funds, as well as multi-jurisdictional and cross-functional

approaches to service delivery;(v) recognition

of the critical importance of effective access to mainstream programs

and services, and clear actions to identify and address barriers to

access;(vi) improving

the collection and availability of data to support informed decision-making,

monitoring of achievements and program evaluation; and(vii) recognising

the importance of capacity building within Indigenous communities.

Particularly relevant

to the issue of benchmarking is the identification of the need to improve

performance in respect of data matters ((vi) above). It was evident to

the CGC that much of the required data for analysing service delivery

was non existent, or partial, or unreliable, or not comparable either

between regions or over time. As the Report says, access to comparable

and reliable data is critical if objective measures of Indigenous need

are to be better incorporated in decisions on the allocation of funds.

The Report notes various data problems, including:

- concerns with

Census data;[72]

- the difficulty

of obtaining administrative data;[73]

- where it does

exist, the lack of comparability;

- at times confidentiality

constraints; and

- the fact that

there are practically no data on what mainstream funds are spent by

region, or by any specific group of people.

Noting that 'a much

greater effort will need to be made by the Commonwealth, the States and

other service providers to improve their comparability, reliability and

availability', the Report recommended that priority must be given to collecting

comparable regional data for many variables. The Report observed that

to achieve good consistent data, the Commonwealth, state and other service

providers needed to, as a matter of urgency:

- identify minimum

data sets and define each data item using uniform methods so that the

needs of Indigenous people in each functional area can be reliably measured; - prepare measurable

objectives so that defined performance outcomes can be measured and

evaluated at a national, state and regional level; - ensure data collection

is effective, yet sensitive to the limited resources available in service

delivery organisations to devote to data collection; - negotiate agreements

with community based service providers on the need to collect data,

what data should be collected, who can use the data, the conditions

on which the data will be provided to others and what they can use it

for; and - encourage all

service providers to give a higher priority to the collection, evaluation

and publication of data.

Finally, the Report

confirmed that without these steps, data will never be adequate to support

detailed needs-based resource allocation. The Report acknowledges that

many of these principles are in fact being followed in work that is underway.

However, it is observed that it is likely to be a long time before the

benefits are obtained in the form of more complete and comparable data

that can be used to measure needs as part of resource allocation processes.

The Report surveyed some initiatives taken to improve data management.

These included:

- Whole-of-government

commitments: In 1997, the Prime Minister asked the Steering Committee

on the Review of Commonwealth-State Service Provision to oversee

the preparation and publication of data on services provided to Indigenous

people. The November 2000 COAG meeting reaffirmed that requirement. - Initiatives

by the Australian Bureau of Statistics: The ABS has work underway

to increase the range and quality of nationwide statistics on Indigenous

people (see below). - Specific Purpose

Payments arrangements: Some of the recent agreements covering the

Commonwealth's Specific Purpose Payments to the States should increase

the availability of information because they require reporting against

agreed indicators of outcomes or outputs. Such conditions are included

in the Australian Health Care Agreements and the agreements under the

Indigenous Education (Targeted Assistance) Act, 2000. There is

a similar requirement covering the provision of service activity data

in the Commonwealth's agreements for funding Aboriginal Community Controlled

Health Services. - Funding and

Service Delivery in Practice: To date, much of the data on performance

indicators, such as that provided under the previous agreements, have

not been comparable across the States. The newer agreements attempt

to obtain the greater comparability that is essential if the data are

to be used for resource allocation purposes. - Initiatives

in functional areas: There has been activity to improve data quality

and availability in areas such as health and housing. In 1996, Commonwealth

and State Housing Ministers agreed to the establishment of a Commonwealth

State Working Group on Indigenous Housing (CSWGIH), which has since

developed an Agreement on National Indigenous Housing Information.

The long term aim of CSWGIH is to develop means of obtaining housing

administrative data that are consistent and compatible with related

data collections. Work has begun on collecting a minimum data set and

developing performance indicators. The work has emphasised the need

for national standards, co-ordination and commitment to the collection

of data, and for additional training and resources to help community

housing organisations collect more reliable data.

A further significant

development was the engagement by the inquiry of the Australian Bureau

of Statistics (ABS) to prepare an experimental index of Indigenous socio-economic

disadvantage. The experimental index does not provide any information

about the absolute level of disadvantage. Having determined that it is

feasible to construct the index, the ABS will examine the feasibility

of sub-dividing the index according to broad functional lines as well

as along geographical lines. ATSIC has provided detailed comments on this

index. [74]

The Government's

response to the CGC Report was discussed in detail in chapter 3.[75]

In brief, the Government

observed that the Report provided a valuable basis for development of

evidence-based policy in Indigenous affairs. The Government set out five

actions that it had agreed to in response to the Report:

- First, the adoption

of Principles for equitable provision of services to Indigenous peoples

[76] to guide its approach to meeting the needs of

Indigenous people; - Second, continued

action by the Government to reduce Indigenous disadvantage through improving

access to mainstream programs and services and by better targeting Indigenous-specific

programs to areas of greatest need, including remote locations; - Third, where

appropriate, the Government will seek to include clear Commonwealth

objectives and associated reporting requirements in respect of inputs

and regional outcomes for Indigenous Australians in renewed SPPs to

States and Territories in the areas of health, housing, infrastructure

and education; - Fourth, where

the Government provides additional funding through mainstream services

for Indigenous clients, and/or provides supplementary funding through

Indigenous specific programs, it is committed to working towards having

the ABS standard Indigenous identifier in the major mainstream administrative

data sets; and - Fifth, the Minister

will report publicly in 2005-06 on the geographic distribution of Indigenous

need, the alignment of mainstream and Indigenous-specific resources

to meet that need and the progress in making mainstream services more

accessible to Indigenous Australians.

6. Australian

Bureau of Statistics

The Australian Bureau

of Statistics continues to be one of the most important sources of statistical

information about Indigenous people and the results are used extensively

by Indigenous communities and organisations and by governments. The release

of the 2001 Census increases the amount of information available with

data being provided through publications, Community Profiles and on the

Internet. Relevant ABS information includes the following:

- Indigenous

Profile: The Indigenous Profile (IP) is part of the Census Community

Profile series, and contains 29 tables of data on Indigenous people

including comparisons with non-Indigenous people wherever possible.

The Indigenous Profile is available for geographic areas including ATSIC

regions. Data available through the profiles include age by Indigenous

status by sex; type of educational institution attending by Indigenous

status by sex; highest level of schooling by Indigenous status by sex;

language spoken at home and proficiency in spoken English by sex; computer

use by Indigenous status by age by sex etc. - The Population

Distribution of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders:

released in June 2002. This publication presents counts for Indigenous

Australians from the 2001 Census, accompanied by information on data

quality to help interpret the 2001 Census counts. Experimental resident

population estimates of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population,

based on the 2001 Census, are also included. Census counts of the Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander population are also provided for small areas

(Indigenous Areas and Locations) and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Commission regions. - The ABS also

completed in 2001-02 the design and development of the first Indigenous

Social Survey (ISS) since the 1994 National Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander Survey (NATSIS). The ISS will survey 12,000 Indigenous

Australians, including those living in discrete Indigenous communities

in remote areas of Australia, and will go into the field in the second

half of 2002. - National Health

Survey: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Results, Australia, 2001

is expected to be released late November 2002. It presents selected

data from the 2001 National Health Survey about the health of Indigenous

and non-Indigenous Australians. Topics include measures of health status,

health actions taken, and lifestyle factors which may influence health.

In response to the

need for Indigenous specific surveys, the planned ABS program for Indigenous

statistics over the next eight years provides for the regular collection

of survey data for a broad range of information requirements, and to respond

to emerging issues, including the production of regional data. While the

2001 National Health Survey included an Indigenous supplement, from 2004,

and six-yearly thereafter, the survey will include a bigger sample and

will provide national, state and territory estimates on some indicators

of health status.

The 2002 Indigenous

Social Survey (ISS), to be conducted every six years, will provide both

national and state/territory estimates that are relevant across sectors,

including health, housing, education, employment, communication, transport,

and crime and justice. The ISS objectives are to collect data on Australia's

Indigenous population in order to explore issues such as levels of and

barriers to participation in society, the extent to which people face

multiple social disadvantages and measuring changes over time in Indigenous

well-being. The ISS will collect a large amount of information in common

with the 1994 NATSIS so that comparisons in the circumstances of Indigenous

Australians can be analysed over time.

The ABS will be releasing,

as part of its Methodology Working Paper series, a Working Paper on the

methodology behind the experimental index of Indigenous socio-economic

disadvantage that was prepared under contract for the CGC (see above).

Depending on feedback from that release, the ABS may consider updating

the index using the results of the 2001 Census of Population and Housing,

and consider incorporating additional data sets as they become available.

In addition to improving

the quality of information generally held in administrative systems accessed

by Indigenous Australians, there is also a need to improve the identification

of Indigenous clients in those systems. The ABS has published a standard

for the identification of Indigenous people in administrative collections

and 'best practice' guidelines for its implementation, and is now working

across jurisdictions to increase the extent of Indigenous identification

and improve the quality of the resulting data. Initial priority has been

given to vital statistics but other data priorities include hospital separations,

community services, cancer registries, perinatal collections, schools

and vocational education and training, housing, and law and justice. The

Government has committed to introducing an Indigenous identifier to Medicare

and the public and community housing program funded through the Commonwealth

State Housing Agreement.

7. Initiatives

at the inter-governmental level related to benchmarking

In September 2002

it was announced that the Commonwealth and Queensland Governments will

work in partnership with the Cape York Indigenous communities to manage

a 'whole-of-government' approach to federal and state Government services,

as part of the 2002 COAG agreement to facilitate a co-ordinated approach

in communities. The new arrangements will let a lead agency 'broker' the

Commonwealth funding for each region, working closely with the community

and state Government.

The Department for

Employment and Workplace Relations will take the lead role on behalf of

the Commonwealth in Cape York. On 19 November 2002 the Commonwealth and

Northern Territory Governments announced agreement that the Wadeye community

will be the second site for COAG's 'whole-of-government' approach to improving

the way governments work with Indigenous communities. The Commonwealth

Department of Family and Community Services and the NT Department of Chief

Minister will take the lead roles in coordinating government agencies

and working with the Wadeye community. Other locations for the whole-of-government

initiative will be determined by discussions between the Commonwealth,

States and Territories and other Indigenous communities.

The Productivity

Commission also recently released the seventh annual report on Government

Services 2002. The report reflects the growing inclusion of Indigenous

statistics in the Report, resulting from the request by the Prime Minister

in 1997 for the Review to give particular attention to the performance

of mainstream services, which was reinforced by the 2000 COAG. The Review

reported on Indigenous-specific housing for the first time. The Review

foreshadowed assistance in its task of reporting Indigenous statistics

from work underway separately to develop indicators to assist in assessing

progress towards meeting the objectives of the COAG Reconciliation Commitment.

Of particular relevance to the Review will be a number of whole-of-government

lead indicators of social and economic disadvantage with a focus on those

issues requiring successful interventions spanning more than one ministerial

council. These include indicators of:

- Family violence

- Law and justice

- Health, housing

and community well-being - Education

The Review also noted

that its task is complicated by the administrative nature of many data

collections that do not distinguish between Indigenous and non-Indigenous

clients. The method and level of identification of Indigenous people appear

to vary across jurisdictions. In this context, the Review cross referenced

to work being undertaken by the ABS (see above).

8. The

Steering Committee framework for reporting on Indigenous disadvantage

In April 2002, COAG

decided to commission the Steering Committee for the Review of Commonwealth/State

Service Provision (SCRCSSP) to produce a regular report against key indicators

of Indigenous disadvantage. The key task of the report 'will be to identify

indicators that are of relevance to all governments and Indigenous stakeholders

and that can demonstrate the impact of program and policy interventions'.

[77]

The Committee has

now provided a draft framework for public comment. Following this, further

consultations with Indigenous communities and other experts will occur

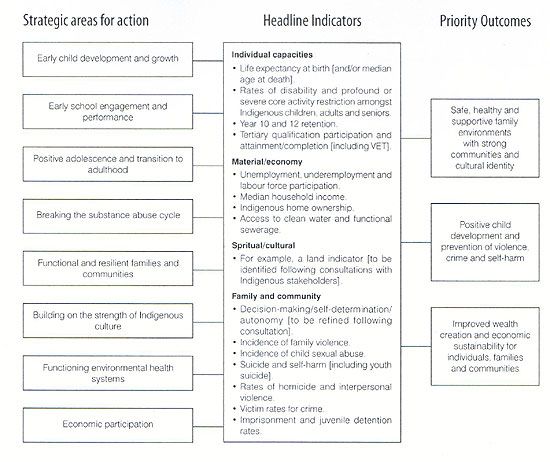

to refine aspects of the framework. A diagram of the framework is shown

in the box below. The framework has three logically related elements,

working back from the priorities listed on the right side of the diagram.

Box

1: Draft framework for reporting on Indigenous disadvantage

Priority outcomes

The three priority

outcomes (right column in above box) are based on COAG's 'priority areas

for policy action' and provide the end focus of the Framework. They are:

- safe, healthy

and supportive family environments with strong communities and cultural

identity; - positive child

development and prevention of violence, crime and self harm; and - improved wealth

creation and economic sustainability for individuals, families and communities.[78]

The framework then

has a two tier set of indicators. These encompass 'headline indicators'

of the higher order outcomes, and a second tier or 'strategic areas for

policy' action. These emphasise the possible need for joint action within

and across governments.

The headline indicators

(shown in the centre column of the Framework) are intended to provide

a snapshot of the state of social and economic Indigenous disadvantage,

given the overall priorities that have been identified. They sit within

four areas of well-being:

- Individual capacities;

- Material/economy;

- Spiritual/cultural;

and - Family and community.[79]

These headline indicators

are higher order outcomes that reflect the longer-term more targeted policy

actions at the second tier. Collective improvements in the headline indicators

should lead to benefits in the three priority outcomes. For example, an

increase in life expectancy at birth and a decline in child sexual abuse

would clearly contribute to the achievement of, for example, 'positive

child development and prevention of violence, crime and self harm' (see

Box below).

Eight strategic areas

for action have been identified (see the left-hand column of the Framework).

For each of these strategic areas, a few key indicators ('strategic change

indicators') have been developed with their potential sensitivity to government

policies and programs in mind. These strategic change indicators are not

intended to be comprehensive - it is not possible to incorporate into

the framework all of the factors that influence outcomes for Indigenous

people. The strategic areas for action have been chosen on the evidence

that action in these areas is likely to have a significant, lasting impact

in reducing Indigenous disadvantage. The rationale for choosing the eight

areas is briefly described below:

1. Early child

development and growth (prenatal to age 3)

Early

child development can have significant effects on physical and mental

health in childhood and adulthood, growth, language development and

later educational attainment.2. Early school

engagement and performance