Native Title Report 2008 - Chapter 3

Native Title Report 2008

Chapter 3

Selected native title cases: 2007-08

![]() Download in PDF

Download in PDF

![]() Download in Word

Download in Word

- 1 Other Court decisions

- 2 Bodney v Bennell – the Noongar appeal

- 3. Western Australia v Sebastian – the Rubibi appeal

- 4 Griffiths v Minister for Lands, Planning and Environment (Northern Territory)

- 5 Blue Mud Bay – Northern Territory v Arnhem Land Aboriginal Land Trust

- 6 Conclusion

Resolving native title is not simply about land, it is an historic

opportunity for the State and Commonwealth to turn a new page in

history...[1]

Federal Court decisions between 2007-08 continue to evidence how the

opportunity to turn the pages of history is rarely realised.

The strong, vibrant and committed Noongar peoples of the South West corner of

Australia had their native title determination over Perth returned to square

one. The Full Federal Court found that the first judge had made a number of

errors in his decision and have sent the case back for consideration by a new

judge, leaving the Noongar peoples uncertain about the future of their rights

over the land. This is despite the Western Australian government openly

acknowledging the Noongar peoples as the Traditional Owners of the land.

The High Court ruled that the Ngaliwurru and Nungali peoples of the Timber

Creek area in the Northern Territory could have their native title rights and

interests compulsorily acquired for the benefit of private business. Although

the case went all the way to the High Court, because of a change of Government

since the case began, the native title interests were never actually acquired.

However, the Griffiths case makes it clear that the Northern Territory

Government can acquire native title rights and interests for any purpose

whatsoever, including for the private benefit of a third party.

Considering the results of court decisions of the past few years, one

can’t help but consider the Yaruwu peoples of the area surrounding Broome

to be lucky that none of the opposing parties found a point of law that could

deny the Yaruwu peoples their native title rights on appeal. However, to have

their rights protected, the matter has been extensively litigated with a number

of decisions delivered by the trial judge and a lengthy judgment in the Full

Court appeal. There may also be more litigation to come, with the Western

Australian government seeking leave to appeal to the High Court. The Yaruwu

peoples will continue the long haul to have their rights recognised, but as the

federal Attorney-General himself has said:

...there will sometimes not be clear cut legal answers or the court’s

decision will not be entirely predictable. So unless participants want to risk

an all or nothing legal throw of the dice, there must be a will on both sides to

devise workable solutions. [2]

While native title continues to be determined excruciatingly slowly through

the parties’ resolution of numerous and complicated issues, the Northern

Territory’s coastal Aboriginal population has one very good reason to

celebrate this year. The High Court recognised that the Northern

Territory’s land rights regime (the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern

Territory) Act 1976), the strongest Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander

land rights law in the country, provides exclusive possession rights to the

intertidal zone. The intertidal zone contains stocks of barramundi, mud-crab and

trepang. With access along 80 percent of the Territory’s coastline now

dependent on permission from the Traditional Owners, Aboriginal Territorians are

well placed to share in the lucrative commercial fishing industry carried on

close to shore.

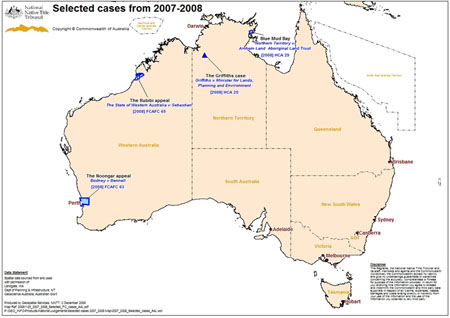

Map 1: Selected cases from 2007-2008

1 Other Court decisions

There were many Federal Court hearings throughout the year that considered

native title issues. A number of these were a direct result of the changes made

to the system in 2007.[3]

In summary, between 1 July 2007 and 30 June 2008, ten determinations of

native title were made[4] and eight

claims were struck out by the Federal

Court.[5]

2 Bodney v Bennell – the Noongar

appeal

In my Native Title Report 2007, I summarised the Federal Court

decision which held that the Noongar people have native title rights and

interests in the southwest corner of Australia, including

Perth.[6] However, in April 2008 the

Full Federal Court found that Justice Wilcox had erred in his judgment in that

case.[7] Allowing the appeal, the Full

Federal Court held that in some respects Justice Wilcox had strayed from the

questions and evidence that Yorta Yorta required him to address. The Full

Court was not prepared to substitute its own answers on the issues of continuity

and connection, and ultimately they could not determine whether or not native

title rights and interests exist. The case was sent back to a new judge to

decide how the matter should

proceed.[8] The parties have agreed to

negotiate the claim.

Once again, the decision highlights how the Native Title Act and its

procedures for a determination often result in unjust outcomes. These outcomes

are not only out of step with the intent of Parliament in passing the Act, but

they go against the government’s policies of acknowledging past injustices

and encouraging reconciliation.

2.1 The case

In Bennell v Western

Australia[9] (the first

Noongar decision), the Federal Court held that the Noongar people, comprising

400 family names, held native title rights and interests over the Perth

metropolitan area.

In the case, Justice Wilcox accepted that a single Noongar society existed in

1829 and that it continued through to today as a body united by its observance

of some of its traditional laws and customs. In his decision, Justice

Wilcox conceded the enormous impact of European settlement and the cessation of

observance of many traditional laws and customs. Nevertheless, consciously

referring back to words used by the High Court in Yorta

Yorta,[10] he said that the

Noongar normative system was:

much affected by European settlement; but it is not a normative system of a

new, different society.[11]

The modifications to traditional law and custom that Justice Wilcox observed

were, in his view, within the parameters of acceptable change, and so the story

of the Noongar was one of continuity and

adaptation.[12]

The decision of Justice Wilcox in the first Noongar case was appealed by the

Western Australian and Commonwealth governments and other parties. The Full

Federal Court allowed the

appeal[13], deciding that Justice

Wilcox had failed to consider two matters that the Noongar claimants were

required to establish under s 223 of the Native Title Act if they were to be

successful in proving their native title.

The first was that Justice Wilcox hadn’t properly considered whether

there had been continuous acknowledgment and observance of the traditional laws

and customs by the Single Noongar Society from sovereignty until today.

The second was that Justice Wilcox hadn’t properly considered whether

the Noongar people had proven a connection with the specific area before the

court. The area the Noongar people were claiming native title over in this case

was the Perth Metropolitan Area. This area was labelled ‘part A’ of

a broader claim area called the Single Noongar Claim, which had earlier been

split in to part A and part B. The Full Federal Court considered that Justice

Wilcox had wrongly taken the view that it was enough that the claimants had

established a connection with the broader area of the Single Noongar claim (part

A and part B combined). Some aspects of the decision have broader implications

for native title and are of concern.

2.2 Successful appeal ground 1 – Continuity

There were a number of aspects of the requirement for continuity that the

Full Federal Court commented on in the Noongar appeal. The Full Federal Court

considered that Justice Wilcox had erred by asking whether the community

survived, rather than whether the laws and customs in relation to land continued

from sovereignty to the present:

Instead of enquiring whether the laws and customs have continued to be

acknowledged and observed substantially uninterrupted by each generation since

sovereignty, [Justice Wilcox] asked whether the community that existed at

sovereignty continued to exist over subsequent years with its members continuing

to acknowledge and observe at least some of the traditional 1829 laws and

customs relating to land. [14]

The Full Federal Court also considered that Justice Wilcox did not give

enough regard to whether the Noongar people had observed their law and customs

‘generation by generation between sovereignty and the present

time’.[15] They considered

that in deciding whether there had been continuity of observance, Justice Wilcox

should have considered whether ‘for each generation since sovereignty,

acknowledgment and observance of the Noongar laws and customs have continued

substantially

uninterrupted’.[16]

As it has been stated in many native title reports, providing such evidence

generation by generation, while being subject to the strict rules of evidence,

is a herculean task for people of an oral culture with a history of

dispossession and generations of children that were removed from their parents.

It is also contrary to Australia’s human rights

obligations.[17]

In his decision, Justice Wilcox was careful to follow the precedent on what

constitutes continuity, as set down by the High Court in Yorta Yorta.

Despite this, the Full Federal Court did not agree with the manner in which he

framed his application of the principles to the Noongar.

Although the Court considered that Justice Wilcox had focused on the

continuity of society rather than continued acknowledgement and observance of

laws and customs[18], they went on

to consider Justice Wilcox’s discussion of those traditional laws and

customs. They then criticised Justice Wilcox for what they considered to be

giving little consideration, as required by Yorta Yorta, to the level of

adaptation and change that was

acceptable.[19]

Finally, the Full Federal Court also criticised Justice Wilcox’s

failure to have regard to anthropologists’ evidence which could have

assisted him in considering whether there had been continuous observance of

traditional laws and customs.[20]

(a) The effects of white settlement?

The law provides that native title does not require strict proof of

continuous acknowledgement and observation of traditional law and custom. In Yorta Yorta the High Court made it clear that there must not be substantial interruption of that observance, nor should there be too much

adaptation or change to the content of the law and

custom.[21] That is, there is some,

albeit very limited, room for traditional laws and customs to have changed since

sovereignty and still be recognised by the law as it stands.

In the first Noongar decision, Justice Wilcox referred to the effects that

white settlement have had on the Noongar people and their traditional laws and

customs. However, as I noted above, he concluded that the modifications to

traditional law and custom that he observed were within the parameters of

acceptable change and

adaptation.[22]

The Full Federal Court did not agree with this reasoning. It held that

Justice Wilcox had made too much allowance for the changes inflicted upon

Noongar society by European settlement. The Full Federal Court stated that

Justice Wilcox should have simply been examining whether the change meant that

the law or custom was no longer

traditional:[23]

[A]cknowledging that the change from home areas to boodjas is a significant

change, his Honour says at [78] that the change is readily understandable

because it was forced on the Aboriginal people by white settlement. The reason

for such an important change is irrelevant: Yorta Yorta HC at

[89].[24]

The Court considered that the law’s requirement that the continuous

acknowledgment and observance of traditional laws and customs be

‘substantially uninterrupted’ as opposed to

‘uninterrupted’ is the mechanism for taking in to account the impact

of European settlement on the community:

...But if, as would appear to be the case here, there has been a substantial

interruption, it is not to be mitigated by reference to white settlement. The

continuity enquiry does not involve consideration of why acknowledgment

and observance stopped. If this were not the case, a great many Aboriginal

societies would be entitled to claim native title rights even though their

current laws and customs are in no meaningful way traditional... In reaching

his conclusion that Noongar laws and customs of today are traditional, his

Honour’s reasoning was infected by an erroneous belief that the effects of

European settlement were to be taken in account – in the claimants’

favour – by way of mitigating the effect of

change.[25]

I do not agree with what the court is implying. An Indigenous person who

revitalises their culture and practices their laws and customs is still

traditional, and also has the right to practice their culture, law and customs

and have those rights recognised, acknowledged and

protected.[26]

However, this finding and the words of the Full Federal Court do not only

deny Indigenous peoples their rights, but it will limit any future judge’s

willingness to comment and give due recognition to the devastating impact of

colonisation on Australia’s Indigenous peoples. More concerning though, is

that it also encourages claimants to deny the catastrophic impacts that

colonisation and other white policies had on them and on their ancestors. At the

Native Title Conference in June 2008, Chief Judge Joe Williams, the Chief Judge

of the Maori Land Court put it as:

In Australia the surviving title approach to transitional justice requires

the Indigenous community to prove in a court or tribunal that colonisation

caused them no material injury. This is necessary because, the greater the

injury, the smaller the surviving bundle of rights. Communities who were forced

off their land lose it. Those whose traditions and languages were beaten out of

them at state sponsored mission schools lose all of the resources owned within

the matrix of that language and those traditions. This is a perverse result. In

reality, of course, colonisation was the greatest calamity in the history of

these people on this land. Surviving title asks aboriginal people to pretend

that it was not.[27]

2.3 Successful appeal ground 2 – Connection

The Full Federal Court also held that the Noongar claimants had not proven

connection to the Perth Metropolitan area specifically. The court held that

Justice Wilcox had erred by not inquiring into whether connection to that

particular area by the laws and customs had been substantially

maintained.[28]

The Full Court noted Justice Wilcox’s assessment that, statistically, a

biological connection between some members of the wider Noongar community today

and the occupants of the Perth area at sovereignty was likely. It said that even

if that were correct, it did not show a present connection by those Noongar

people specifically to the Perth area.

The conclusion reached by the Court raises questions about how strategies for

running a native title case can be employed by governments and non-claimant

parties to contest a native title claim. In the Noongar case, the State had

initially suggested that the Single Noongar Claim be split in to two parts. This

decision shows that a ‘segmentation’ strategy by respondents to

whole of country native title claims may actually be rewarded by the kind of

reasoning adopted by the Full Federal Court in this case. That is, if there are

uneven levels of sub-group connection within a diverse claim area, a more

built-up area could be hived off from what would otherwise possibly be a

positive determination of native title. Yet again, this interpretation

privileges a technical and legalistic approach to assertions of country, over

holistic ones based in Indigenous cultural norms.

2.4 The future of the Noongar peoples’

claim

The future of the Noongar peoples’ claim is uncertain. The Full Federal

Court refused to determine whether native title existed in the

area.[29] The court remitted the

question of whether native title rights and interests exist over part A (the

Perth Metropolitan Area) to the docket judge, but left it to that judge to

decide whether to determine part A separately or whether to consolidate it with

a hearing over the remaining part

B.[30]

At the time of the decision, Glen Kelly, the chief executive of the South

West Aboriginal Land and Sea Country (SWALC), the Native Title Representative

Body for the region, said ‘[w]hat this decision means is back to square

one, absolutely back to the beginning of proceedings’. But, he said, it

was not a loss for the Noongar people. ‘They didn't go so far as to make a

ruling that native title does not exist.’

SWALC Chairman Ted Hart said that while they were ready to negotiate with the

governments, the State's ‘very aggressive’ appeal had been insulting

to Noongar people. However, after appealing the decision rigorously, the Western

Australian government said that:

Native title agreements have the capacity to deliver much, much more if

together we can demonstrate the courage, persistence and flexibility to make now

big decisions with long term

implications.[31]

And it has stated that it:

[Respects] the special relationship of Noongar people with land in the

South-West and we look forward to continuing our negotiations with them. With

this decision, we now have a clear and consistent understanding of the law, one

that will give both the Government and Noongar people a solid platform for

negotiations.’

The federal Attorney-General also signalled his

preference for negotiating an

outcome.[32]

All parties have since agreed to meditate the claim. The mediation is limited

to part A of the claim, and the parties have agreed that part B will be

deferred. The parties will consider what areas of the claim will not be

considered (that is, over which the Noongar peoples’ rights have

effectively been extinguished) and negotiate the six underlying regional claims

asserted by the small distinct groups that form the single Noongar

population.[33]

While the outcome of the negotiations may take many more years, there appears

to be increased and better engagement from all sides. The Western Australian

Government is taking an active part in the negotiations, with the Australian

Government and other respondents taking a minor

role:[34]

[The Western Australian government and Noongar peoples] have endeavoured to

thaw what was previously a frosty relationship. [35]

Since this time, the Western Australian government has changed, and I hope

that the new government will approach the negotiations with a willingness and

commitment to achieving a just outcome.

3. Western Australia v Sebastian – the Rubibi

appeal

During the year, the Yawuru peoples’ native title determination was

confirmed by the Full Federal

Court.[36]

The State of Western Australia and a competing claimant appealed different

aspects of the first instance decision of Justice

Merkel[37] that determined that the

Yawuru people held native title rights and interests over areas in and around

the Western Australian coastal town of Broome. The Full Federal Court upheld

Justice Merkel’s findings in relation to communal native title, but

overturned some of the findings on extinguishment, holding that there were more

extensive native title rights than Justice Merkel had found. The decision paves

the way for a slightly strengthened native title determination, amidst wider

negotiations between the State and Rubibi over native title, compensation and

heritage.

Although the Yawuru peoples were ultimately successful in having their native

title rights and interests recognised, the case has taken far longer than it

should have. Justice Merkel resolved the basic ‘native title issues’

in ‘interim’ judgments delivered in 2005 and 2006. Even earlier, in

2001, he determined the Yawuru to be the communal native title holders to

adjacent territory, an Aboriginal law ground on the outskirts of Broome. Yet

respondents continued to argue the native title issues on appeal. The fact that

the State has sought special leave from the High Court to re-agitate some

extinguishment issues again shows how litigious behaviour frustrates outcomes,

long after the ‘right people’ with whom to settle matters have been

identified. This approach is contrary to the less litigious approach that all

governments have now committed to.

3.1 The case

The background to the case is complicated, with multiple Federal Court

decisions handed down since the application was made in early 1994. Some of the

earlier decisions dealt with preliminary issues, such as who was an appropriate

party to the litigation. Unusually, the judge’s final conclusions on the

native title application were spread across two ‘interim’ sets of

published reasons as well as the final judgment and determination delivered in

April 2006.

There were two competing native title groups in relation to the land and

waters in and around the township of Broome in Western Australia.

The first claim, referred to as the ‘Yawuru claim’, was made by

12 applicants on behalf of the Yawuru community. The claim area includes three

sub-areas: the Yawuru, the Walman Yawuru, and the Minyirr clans’ claim

areas.

The second competing claim, the ‘Walman Yawuru claim’ was made by

three applicants on behalf of a subset of the Yawuru community – being the

Walman Yawuru clan. The Walman Yawuru applicants were opposed to the assertion

of communal native title, arguing that native title in the area is clan-based

rather than communal.

Both of the claims were opposed by the State of Western Australia, the

Commonwealth, and the Western Australian Fishing Industry Council (WAFIC).

The Western Australian and federal governments argued ‘that neither

claim group could demonstrate that it possessed rights and interests in any land

or waters in the Yawuru claim area under a normative system of traditional laws

and customs which has had a continuous existence and vitality since

sovereignty’.[38] They

disputed several aspects of the Yawuru claimants’ case, and argued that in

the northern portion of the claim area native title right and interests were

traditionally held by a separate society, the Djugan people.

On 28 April 2006, Justice Merkel made a native title determination in favour

of the Yawuru community.[39] In that

decision, Justice Merkel found that the traditional laws and customs of the

Walman Yawuru claimants were the same as those of the Yawuru community.

Consequently, the Walman Yawuru claim was dismissed, with Justice Merkel finding

that they did not have separate native title rights and interests, but shared in

the communal native title as a sub-group of the Yawuru community.

All parties appealed different aspects of the decision, and the court heard

16 consolidated issues together. These were divided into issues which went to

the heart of the findings of native title rights and interests and those which

went to extinguishment.

The Full Federal Court dismissed the aspects of the appeal relating to the

content of the native title rights and interests. They clarified who held native

title, finding that it is held by the Yawuru claimants as communal native title

rights and interests in the whole of the claim area. They dismissed the appeal

of the Walman Yawuru, upholding Justice Merkel’s finding that they are a

sub-group of the Yawuru community, and do not have any separate native title

rights or interests in their capacity as clan members.

With regard to the aspects of the appeal dealing with extinguishment, the

Full Federal Court upheld some findings but agreed that Justice Merkel had erred

in respect of others. The net result was that native title had not been

extinguished in some areas Justice Merkel considered it had been.

3.2 Content of native title rights and

interests

The State appealed (unsuccessfully) on several issues that have featured many

times before in Federal Court litigation. I offer three examples to illustrate

the point I wish to make.

First, the State argued that Justice Merkel was wrong to find that a Yawuru

individual’s entitlements as a native title holder could derive from the

mother’s side and not just the father’s side (that is, under a

cognatic system rather than a patrilineal one). The objection is that cognatic

systems in the contemporary era show a lack of continuity with the

pre-sovereignty era and that is sufficient to defeat a native title claim. It is

an objection that has been made in trials and appeals repeatedly by respondents

in recent years,[40] and is mostly

unsuccessful, as it was here in the Rubibi case.

Secondly, the State objected in various ways to the characterisation of

Yawuru entitlements as a “communal” native title. As with other

cases where similar objections have been made (also

unsuccessfully),[41] this was allied

to arguments that highlighted allegedly distinct sub-group identities. The

purpose of such arguments is to defeat the assertion of a communal native title

on behalf of a regional grouping.

Thirdly, respondents have attempted several times to argue that declaration

of a township is sufficient to defeat the beneficial operation of section 47B.

This section allows past extinguishment to be disregarded, but its effect is

nullified where the area is covered by a proclamation that “the area is to

be used for public purposes or for a particular purpose”. The argument

that declaring a township precludes reliance on section 47B has now been

rejected by a Full Court on at least three

occasions.[42]

This repeated litigation of issues designed to thwart native title

recognition, despite several rebuffs at trial and appellate level, illustrates

the litigious mindset that has dominated native title in Australia.

I hope that the new flexible and less technical approach to native title that

each government has committed to will mean that we see a lot fewer of these

arduous and technical appeal grounds raised at every point of the determination.

(a) Descent system

Justice Merkel had found that while the descent system of the Yawuru

community was traditionally patrilineal, their traditional law and custom had

‘contingency provisions’, which allowed others to lawfully become

members of the group. He accepted that, by an evolutionary process, classical

patrilineal rules for landholding had melded with these contingency provisions

into a cognatic or ambilineal

system.[43]

The Western Australian Government argued that the primary judge erred in this

finding. They argued that in fact the traditional law at the time of sovereignty

was always patrilineal descent and therefore the current system is proof of a

lack on continuity of traditional law and custom.

The Full Federal Court examined the evidence and dismissed this ground. In

doing so they upheld Justice Merkel’s finding that:

...whatever the precise structure and traditional definition of the Yawuru

people at sovereignty might have been, a change from a community similar to a

patrifileal clan-based community at or before sovereignty to a cognatic or

ambilineal based community is a change of a kind that was contemplated under the

‘contingency provisions’ of those traditional laws and

customs.[44]

(b) Succession

The Full Federal Court upheld Justice Merkel’s primary finding that the

Djugan shared a common normative system with the Yawuru at sovereignty and that

the Djugan, heavily impacted by colonisation, had been absorbed into the wider

Yawuru community. The State also appealed against the primary judge’s

alternative finding on the issue. This was that if, on appeal, the Djugan were

shown not to be a sub-group of the Yawuru community at sovereignty, then any

rights and interests that the Djugan may have had in the northern area of the

claim area had passed to the Yawuru community in accordance with traditional

rules of succession.

Justice Merkel had considered that the evidence from the Yawuru elders showed

that principles of succession formed part of the traditions practiced in the

Yawuru claim area.

However, the State argued that, while the judgment in Yorta Yorta recognised rules for the transmission of native title rights, the comments were

directed to the intergenerational transmission of rights and interests within

the claim group – rather than between claim groups. The State argued that

‘succession is not an acceptable basis for a finding of native title in

circumstances where the purported succession of rights involves groups having

different normative systems at

sovereignty’[45], and

disagreed that the evidence in the Rubibi trial supported succession

between tribes.

The Full Federal Court found that while the evidence on transmission rules

was slight, it was sufficient to sustain Justice Merkel’s conclusion. The

Full Court noted that there were only two practical possibilities: that the

Yawuru have ‘imperialistically’ taken over the Djugan areas or that,

in accordance with the common traditional laws and customs of the two clans, the

Yawuru have succeeded to the northern part of the Yawuru claim area over time,

as the Djugan have reduced in

numbers.[46] The Full Court was

prepared to accept that the evidence existed to support the latter

conclusion.

3.3 Extinguishment of native title rights and

interests

Various grounds of appeal also dealt with Justice Merkel’s findings

about where native title has been extinguished and how that had occurred.

Both applicants and respondents argued, for instance, that Justice Merkel had

incorrectly applied s 47B of the NTA. This section says that past extinguishment

can be ignored if, at the time of claim, the land is essentially unallocated and

unused except that it is ‘occupied’ by the native title

holders.[47] Its net effect is that

recognition of ‘exclusive possession’ native title becomes a much

stronger possibility in the relevant area.

In relation to the extinguishment issues before the Full Federal Court, a

number of appeal grounds were dismissed, but some were successful. The Full

Federal Court overturned some of Justice Merkel’s findings:

- The Yawuru people had proven that they had occupied some small areas at

Kennedy Hill, in and around Broome, at the time the native title application was

lodged (enabling past extinguishment to be disregarded). - Reserve 631 was not validly created because the purpose for its creation was

too broad and it didn’t comply with the necessary regulatory requirements

at the time it was created. - The trial judge wrongly assumed that the Broome cemetery reserve had been

vested in trustees, but the Western Australian government had not discharged the

evidentiary onus to show this had actually occurred.

These findings

mean that native title may exist in some areas it was previously thought not to,

and that some native title rights may now be exclusive in areas where it was

previously thought to be non-exclusive.

The Western Australian government has sought leave to appeal to the High

Court in relation to the establishment of Reserve 631 for a public purpose and

the alleged vesting of the cemetery reserve in appointed

trustees.[48]

3.4 The future of the Yawuru peoples’

claim

In his first instance decision, Justice Merkel stated:

The determination of native title that is now able to be made brings to an

end an epic struggle by the Yawuru people to achieve recognition under

Australian law of their traditional connection to, and ownership of, their

country.[49]

However this is unfortunately not the end, with the Western Australian

government effectively refusing to recognise the breadth and existence of the

Yawuru peoples’ rights. After the lengthy Full Federal Court appeal, the

WA government is seeking leave to appeal to the High Court. In the meantime, the

parties continue to negotiate over native title, heritage and compensation.

However the claim, which began over a decade ago, has proceeded through

various attempts at mediation, the majority of which have failed and so the

matter continues to come before the

courts.[50] The parties have many

significant issues to grapple with, including finalising extinguishment issues

and considering liability to pay compensation or whether other remedies are

available.[51]

4 Griffiths v Minister for Lands, Planning and

Environment (Northern Territory)

On 15 May 2008, the High Court handed down the

Griffiths[52] decision. The case was

an appeal by Alan Griffiths and William Gulwin on behalf of the Ngaliwurru and

Nungali peoples, the Traditional Owners and native title holders for land around

the town of Timber Creek in the Northern Territory (NT). The Traditional Owners

were challenging the Northern Territory government's power to compulsorily

acquire their native title rights and interests under the Lands Acquisition

Act 1989 (NT) (the LAA). The land was then going to be granted to private

third parties for their commercial use.

The High Court found that the legislative provision to acquire land

‘for any purpose

whatsoever’[53], including

native title, provided the power for the Minister to acquire the land. In

exercising this power, the Minister legitimately extinguished the native title

rights and interests in the land under the Native Title Act. In effect, the

legal system had finally recognised the Ngaliwurru and Nungali peoples’

native title rights and interests, only to confirm that at any time they can be

taken away once again for the benefit of another person who wanted to use their

land.

The government of the Northern Territory changed during the case. The new

government changed the existing policy and decided not to proceed with the

acquisition. The case demonstrates the tenuous protection of the relevant native

title rights and interests under the law. Only the policy position of an

incumbent government saves them. It also raises a more significant question

about the extension of compulsory acquisition powers for the benefit of private

interests and the appropriate application of these powers to Indigenous land

rights.

4.1 The case

The land around Timber Creek in the Northern Territory was vacant crown land

that had previously been subject to pastoral leases which had lapsed.

In 1997, a private individual applied under the Crown Lands Act 1989 (NT) (the CLA) to purchase one of the

Lots.[54] Over the next few years,

the Northern Territory Minister for Lands, Planning and the Environment (the

Minister) considered the individual’s and subsequent other private

developers’ plans for the surrounding Lots.

The Minister issued notices proposing to acquire all the interests in the

land, including the native title rights and

interests.[55] The government then

intended to grant the land as Crown leases to the private entities which had

submitted development plans. The notices were unsuccessfully appealed by the

Traditional Owners to the Northern Territory Lands and Mining Tribunal. They

then proceeded to the Supreme Court, which found in favour of the Traditional

Owners. The Northern Territory Government successfully appealed the Supreme

Court decision to the Court of Appeal, and the Traditional Owners sought leave

to appeal to the High Court.

During this time, the Traditional Owners lodged native title claims over the

area. Their native title was determined in August 2006 by the Federal Court who

recognised that ‘the Ngaliwurru and Nungali peoples had maintained their

long-standing connection with the Timber Creek district in spite of early

violent contact with European

settlers...’[56] The Full

Federal Court later varied the native title determination in the Traditional

Owners’ favour, holding that they hold their native title rights and

interests exclusively.[57]

The Traditional Owners, who held native title interests that were now

formally recognised, appealed to the High Court, challenging the Northern

Territory Government’s compulsory acquisition on two alternative

grounds:

- That the compulsory acquisition of native title rights and interests only is not a valid extinguishment of native title under the Native Title

Act. Section 24MD(2) of the NTA provides that extinguishment of native title by

compulsory acquisition is only valid when all interests in the land are

compulsorily acquired. They argued that the word ‘all’ requires that

other, non-native title rights and interests must also be acquired; in this case

there were no such interests, consequently the extinguishment was

invalid.[58] - That the LAA did not give the Minister the power to acquire land from one

person to enable it to be sold or leased for the private use of

another.[59]

However,

Justice Kirby put the ultimate question before the court as being:

... the particular problem that is now before this Court, namely a suggested

deprivation and extinguishment of hard-won native title interests of

[I]ndigenous Australians for the immediate private gain of commercial interests

of other private interests, without needing the consent of the indigenous owners

and their satisfaction with the price to be paid for the peculiar value to them

of their native title interests.[60]

In May 2008, the High Court handed down its decision allowing for the

acquisition and extinguishment of the native title rights and interests held by

the Ngaliwurru and Nungali peoples.

4.2 Ground 1: Acquiring native title only, where

no other interests in the land exist

The High Court unanimously held that section 24MD of the Native Title Act

allows for compulsory acquisition that would result in the extinguishment of

native title when no other interests in the land exist, as well as when native

title rights co-exist with other

interests:[61]

All of the judges agreed that ‘all’ should be understood as

‘any and all’. Any other reading, they suggest, would have an

arbitrary result. Gleeson CJ pointed out that the key purpose of the provision

of the NTA is to avoid racial

discrimination...[62]

The Court indicated that it was artificial to interpret the power of

acquisition as confined only to situations where native title co-existed with

other interests in the acquired land.

4.3 Ground 2: Acquiring land for the benefit of

a third party

When considering the extent of the powers given to the Minister under the Lands Acquisition Act, the court was split five judges to two. The

majority (Justices Gummow, Hayne, Heydon, with Chief Justice Gleeson and Justice

Crennan agreeing) held that the LAA allowed for the compulsory acquisition of

land, including native title rights and interests in that land, for any purpose

whatsoever. Justices Kirby and Kiefel gave separate dissenting judgements.

The majority examined section 43 of the LAA, which empowers the Minister to

compulsorily acquire land ‘for any purpose whatsoever’. They agreed

that, whether or not there were any ultimate limits on the broad phrasing of

section 43, the power at least includes acquisition ‘for the purpose of

enabling the exercise of powers conferred on the executive by another statute of

the territory’. In this case, section 9 of the Crown Lands Act provides that the Minister may grant estates in fee simple or lease Crown Land.

The case raised ‘a central question of the power of the Crown to

acquire the private rights of one citizen (or group of citizens) for the

immediate benefit of another private

citizen’.[63] However, the

majority considered that the NT legislation rendered previous cases which

establish ‘a clear line of authority against local governments interfering

with the private title of A for the private benefit of

B’[64] inapplicable.

However, the two dissenting judges considered that the LAA did not grant the

Minister the power to acquire land for the private benefit of a third party.

Justice Kiefel considered there must be read in to section 43(1) of the LAA a

requirement that the acquisition be for a public purpose. She considered this on

the basis of previous case law and the wording of the LAA. Specifically, she

considered that section 43 requires that the acquisition be for a purpose which

is connected with the Minister’s act of acquiring the land. That is, that

there should be a government purpose. In this case she found that:

It is abundantly clear that in the present case no use by the Minister or the

Territory is proposed...the exercise of the power stands as no more than a

clearing of native title interests in order to effect leases and grants of the

land for private purposes. [65]

Justice Kirby’s lengthy dissent took a holistic approach, considering a

number of key principles, including the importance of native title and its

position in the Australian legal system. He found that in order the government

to acquire private interests for the benefit of a private third party to be

valid under the LAA, it must be enabled by a specific and unambiguous provision

of the Act[66] and that, unless such

an unambiguous provision exists, ‘the well-established principles of the

common law that are here invoked...on behalf of the Aboriginal native title

holders’, should be

upheld.[67]

4.4 Justice Kirby’s dissenting

judgment

Justice Kirby’s dissent should be examined carefully as it raises a

number of significant issues that the government and the broader public should

consider. In his dissent, Justice Kirby considered the interpretation of the LAA

through examining legal authority, legal principles and legal policy which

‘demand respect for the legal rights to property of private individuals in

Australia generally, and in particular the legal rights of Aboriginal

Australians...’[68] He focused

on the general principle of common law which requires that legislation depriving

individuals of established legal rights must be clear and

unambiguous:[69]

Insisting upon this interpretation of the LAA is not to be regarded as

denying the attainment of the constitutionally valid purposes of legislation,

enacted in concededly broad terms. Instead, it is a course adopted out of

respect for:

- the legislature's normal observance of great care in the deprivation of

the basic rights of individuals, whoever they may be- the special care to be attributed and expected (in light of history) to

deprivation by a legislature of the native title rights of Aboriginal and other

indigenous communities- the serious offence which the opposite construction of the LAA does to

common or hitherto universal features of legislative compulsory acquisition in

our legal

tradition.[70]

He went

on to consider a number of other legal principles, including the exceptional

nature of any compulsory acquisition:

From the earliest days of compulsory acquisition legislation in England and

Australia, statutory provisions affording powers to governments or their

agencies to acquire the property interests of individuals have been interpreted

with considerable vigilance to protect those affected against abuse. [71]

He considered that this principle has greater significance when the

acquisition is being used to benefit or advantage another person’s private

interests. He referred to United States Supreme Court decisions which interpret

the Constitution as precluding the legislature from having the power to take

property off one person for the sole purpose of transferring it to another.

Justice Kirby also referred to British legal commentary that states:

[T]he assertion of a private form of eminent domain – the 'one-to-one

transfer of property' for private rather than public benefit – remains

anathema in most legal traditions. This is so even though the taking is coupled

with an offer of full monetary compensation. It seems wrong that the coercive

power of the state should be used to force an unconsented transfer from A to B

where the operation of the open market has failed to generate the required

bargain by means of normal arm's length

dealing.[72]

Justice Kirby did not think that these common law presumptions had been

overridden by the general language of the LAA that allowed for acquisition

‘for any purpose whatsoever’:

Although a court's usual obligation is to give effect to the purpose of the

legislature derived from the statutory text, when important values appear to

have been overlooked, a court is entitled to conclude that apparently broad

language does not, in law, achieve departure from those values, without an

explicit indication to this effect in the

text.[73]

Particularly relevant for this Report are Justice Kirby’s comments on

the application of these principles to native title. Justice Kirby recognised

that the general principles on the exceptionality of acquisition were even more

significant in this case because of the nature of the rights being acquired,

that is, because they were acquiring native title.

He considered that native title, which is not of the same origin or character

as other property interests is ‘more than an interest of an ordinary

kind’:[74]

Thus a fundamental distinction between the acquisition of ordinary interests

in land and the existence of interests giving rise to native title in Australia

is the special spiritual relationship that exists between the native title

owners in the land...[75]

He referred to the various High Court cases in Australia that had recognised

this special connection and relationship with the

land.[76] Consequently, approaching

Indigenous interests in the land in the same way as approaching non-Indigenous

interests in land would be:

to miss the essential step reflected in the belated legal innovation

expressed in Mabo. That new legal principle accepted that the common law

of Australia would give recognition to native title without altering that title

or imposing on it all of the characteristics of other interests in land derived

from the different ... law of land tenures inherited by Australian law from

English law upon settlement.[77]

To pretend that native title in the Northern Territory ‘is no more than

another interest in land ... would be to ignore both legal and social reality...

Importantly, it would needlessly involve a failure of our law to live up to the

promise of Mabo’:[78]

Nevertheless, against the background of the history of previous

non-recognition; the subsequent respect accorded to native title by this Court

and by the Federal Parliament; and the incontestable importance of native title

to the cultural and economic advancement of indigenous people in Australia, it

is not unreasonable or legally unusual to expect that any deprivations and

extinguishment of native title, so hard won, will not occur under legislation of

any Australian legislature in the absence of provisions that are unambiguously

clear and such as to demonstrate plainly that the law in question has been

enacted by the lawmakers who have turned their particular attention to the type

of deprivation and extinguishment that is propounded. In Mabo Brennan J

cited authorities from Canada, the United States and New Zealand that support

the contention that ‘native title is not extinguished unless there be a

clear and plain intention to do

so’.[79]

In conclusion, he found that if the legislature wants to modify or abolish

native title, it must expressly address that outcome in the

legislation.[80] ‘In the

absence of such legislative particularity, any impugned law will be interpreted

protectively and construed in favour of Indigenous land

rights’:[81]

Australian legislatures, on this subject, must be held accountable to the

pages of history. If they intend deprivation and extinguishment of native title

to occur, reversing unconsensually despite the long struggle for the legal

recognition of such rights, then they must provide for such an outcome in very

specific and clear legislation that unmistakably has that

effect.[82]

4.5 The outcome of the case – disposable

native title

Justice Kirby acknowledged the disappointing fact that had the private

individual not made the application to purchase the land (triggering the first

and then subsequent acquisition notices), then the ‘inference is

inescapable that the Ngaliwurru and Nungali peoples, living in and near Timber

Creek, would have continued to use the land in harmony with the activities of

the [private individual’s]

interests...’:[83]

...Whether it was actually necessary, in order to procure the economic

benefits, to acquire the interests of the Ngaliwurru and Nungali peoples by

compulsion rather than by free negotiation in the open market, depriving them of

rights of entrepreneurship that would otherwise belong to them by reason of

their native title, is a matter of

speculation.[84]

Yet this is the path that the Northern Territory government (at the time)

chose to take; easily disposing with Indigenous land rights without agreement or

discussion, as it suited them.

In the end however, after years of litigation and this High Court decision,

the Northern Territory government did not acquire the native title. This is

because in 2001 the Northern Territory voted in a new government, with a

different policy towards Indigenous land and native title. It is of course

positive that the government changed its tune; however, the protection of native

title and the respect for Indigenous land rights should not be left to the whim

of the Government of the day, but should be protected by law.

This issue is not unique to the Northern Territory but applies across the

country.

How native title is and can be acquired by governments differs in each state

and territory. Each jurisdiction has separate laws providing for the compulsory

acquisition of native title rights and interests and if relevant, the land

granted to Aboriginals or Torres Strait Islanders under land rights regimes.

These laws provide different procedural requirements for acquiring land,

including when and how to give notice, how and when agreements can try and be

reached and appeal procedures. They also differ in the reasons for which native

title, or any other property rights, can be acquired.

In his dissenting judgment in Griffiths, Justice Kirby outlined the sui

generis nature of native title, and the history of Indigenous land rights in

Australia as reasons why the acquisition of native title should be treated

differently to other interests in land. This approach is supported by the

international human rights framework. I recommend that governments pursue a

human rights based response which is consistent across state, territory and

federal legislation.

(a) A human rights

response

(i) The international human rights

framework

From as early as 1995 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice

Commissioners have raised the human rights implications of a failure to

negotiate or gain the consent of Traditional Owners before their native title

rights are taken away once

again.[85]

As the then Social Justice Commissioner, Mick Dodson, said in 1995,

international human rights standards require negotiation and consent before

interference with vested rights can legitimately occur. Interference with

property without even negotiating with the owner would interfere with property

in a manner contrary to Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human

Rights[86]. Consistent with the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial

Discrimination (the

CERD)[87], Indigenous peoples

are entitled to enjoy our property rights free from

discrimination.[88]

In general comment 23 to the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of

Racial Discrimination specifically provides for this situation, calling on State

parties to:

... recognise and protect the rights of indigenous peoples to own, develop,

control and use their communal lands, territories and resources and, where they

have been deprived of their lands and territories traditionally owned or

otherwise inhabited or used without their free and informed consent, to take

steps to return these lands and

territories...[89]

The Committee also recommends that states:

Ensure that ... no decisions directly relating to [Indigenous peoples’]

rights and interests are taken without their informed

consent.[90]

The specific rights of Indigenous peoples with regards to their land have

been further entrenched in the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Article 28 requires that Indigenous peoples give their free, prior and informed

consent before the approval of any project affecting our lands.

In the Native Title Report 1997, the compulsory acquisition of native

title for the benefit of third parties was discussed in light of the Wik 10

point plan.[91] The original NTA

passed by Parliament provided for negotiation between the government, the

registered native title party and other stakeholders in relation to any

compulsory acquisition. Part of the Wik 10 point plan amendments, was to remove

the right to negotiate for the acquisition of native title for the benefit of

third party private interests when the land involved is inside a town or

city.[92] The amended Act reduced

the right to negotiate to a much lesser procedural right to

object.[93] In the Native Title

Report 1997, the Social Justice Commissioner Mick Dodson raised concerns

that state or territory legislation (none of which provided for acquisition for

the benefit of a third party interest at this stage) would be amended to allow

acquisitions for private purposes. Even though any such amendments would have to

apply to all land in the jurisdiction to avoid breaching the Racial

Discrimination Act 1975, Dodson considered that introducing state or

territory laws with such powers in response to the Wik amendments, and therefore

primarily for the purpose of acquiring native title, would in fact be

discriminatory.

In the same year, the Lands Acquisition Act was amended. Although the

compulsory acquisition power was already broadly worded, stating that ‘the

Minister may, under this Act, acquire land’, it was amended in 1998 to

include the words ‘for any purpose whatsoever’. After this point,

the Northern Territory government has issued 82 compulsory acquisition notices,

and on every occasion the land was claimed or claimable by Aboriginal

people.[94] Dozens of these have

been town lands, and were therefore acquired without a right to negotiate the

acquisition.[95]

(ii) Consent as a traditional law and custom

The Native Title Act attempts to translate Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islanders’ traditional laws and customs into a form of western legal

property right. In doing so, it unwittingly destroys many of the sui

generis characteristics of the very laws and customs it was apparently

designed to recognise and protect. One of these characteristics is the notion of

controlling access to and activities on traditional estates, which is a

consistent feature of Indigenous law. It is ‘what a Pitjantjatjara man

once defined as “the first law of Aboriginal morality – always

ask”’.[96]

The cultural underpinning of a right to negotiate was presented in the

evidence in the Croker Island

case.[97] In that case Mary Yarmirr

stated that the members of a Yuwurrumu (an estate group) had the right to make

decisions about all aspects of the estate including a right to be asked and to

apply conditions to entry:

In respect of my law and my culture, as I have respect for another culture,

I’d ask them to come towards us and ask permission.Q: All right. And if they ask permission, what rights would you have by your

law in the way that you responded to their request?

A: As a yuwurrumu holder I would then sit down and negotiate and come to a

settlement.

Q: Would you be able to say by your law ‘No’ to

them?

A: Yes I have done that on numerous occasions.

Q: In respect of

what?

A: In respect to oil exploration at Summerville Bay.

Q: So there

have been requests for oil exploration at Summerville Bay?

A: That is

correct.

Q: And what has happened on these occasions?

A: On those occasions, because they identify where they like to explore and

it was on some of our sacred areas, we said to them due to respecting our old

traditional laws and our culture we’d ask you to reconsider, maybe looking

at another to avoid those sacred areas, which they did.

Q: All right. If the area was a suitable area as far as your yuwurrumu was

concerned would you have the right to say not ‘no’ but

‘yes’?

A: Yes.

Q: And you have spoken [of] negotiation. Would you have the right to

say yes but subject to conditions?

A: That’s correct.

There is no doubt in Mary Yarmirr’s mind that according to her

yuwurrumu there was a right in her people to control entry onto their seas and

to apply conditions to that

entry.[98]

This right was even recognised in the Griffiths native title decision. In the

native title determination for the Ngaliwurru and Nungali

peoples[99], the Full Federal Court

found that the Traditional Owners held their native title rights and interests

exclusively because of the evidence presented about their control of the land:

The indigenous witnesses designated as ‘yakpalimululu’, someone

who would deny others access to certain foraging areas...If a white person

wished to go on the land that person would be expected to ask permission first.

The purpose of the request would be to enable important sites to be identified

presumably so that they might be

protected.[100]

When the Native Title Act was first passed by Parliament, there was some

protection from compulsory acquisition through a right to negotiate. This

protection was considered by many to have had its origins in traditional law and

custom. It has been said by previous Social Justice Commissioners that the right

to negotiate provisions (as they were originally enacted) were not a

‘windfall accretion’ or gift of government, but an intrinsic

component of native title to the

land.[101]

The control of entry to land is not an ‘add on’; it is

fundamental to the protection and maintenance of country:

Ownership of country and knowledge is manifested through rights to be asked.

While Aboriginal people rarely say ‘no’, provided that the request

is in keeping with what is appropriate for a given place or use, they insist

upon the right to be asked, and hence upon their right to say either

‘yes’ or

‘no’.[102]

As was pointed out in the Native Title Report 1996, Justice Woodward

recognised this in his report, which led to the enactment of the Northern

Territory’s land rights regime, when he said that to deny Aboriginal

owners the power to control access and activities on their land was ‘to

deny the reality of their land rights under traditional

law’.[103]

The fact that the right to control access is an intrinsic right of native

title has been forgotten as the procedural rights attached to native title have

been amended or removed. Now native title rights are considered to be in the

most precarious position of all Australian property rights.

(iii) Protection of native title rights

Native title is not simply another property right, but is sui generis in character, and should be protected in unique ways to recognise this. It

is not good enough for governments to disregard native title, compulsorily

acquiring it and extinguishing it as it sees fit, sometimes using the poor

justification that it could possibly do the same to other property interests in

land:

It is misconceived to look to the title-rights of another genus of title and

to use those rights as a benchmark of equal treatment where detriment results.

This approach ignores the substantive difference in the source and character of

a sui generis title. It fails to provide substantive equality of

protection to native

title.[104]

Similarly, it is not good enough for governments to simply have a policy of

acquiring native title rights as a last

resort.[105] Native title rights

and interests and other Indigenous land rights require greater protection by

law.

The Native Title Report 1998 included a discussion on the right to

negotiate, rebutting the argument that it would be unfair if native title

holders had a right to negotiate in relation to certain compulsory acquisitions

while other holders of property rights do not:

[where] you have a situation where other Australians are sharing the land, we

do believe— and we hold this view from the basis of a fundamental

philosophical position— that procedural rights should be the

same.[106]

The arguments for distinct protection of Indigenous land rights that were put

forward in the Native Title Report 1998, the Native Title Report

1996 and Justice Kirby in his dissent in the Griffiths decision, all

apply:[107]

This notion of equal protection, accorded through holding exactly the same

procedural rights as others, determinedly sets its face against the fact that

the titles of others do not derive their nature and incidents from Indigenous

law. The right to control and mediate access to traditional estates is not some

sterile right of prohibition. It is integral to our manifold traditional rights

and obligations to land which embrace social, cultural and spiritual life, as

well as access to resources.[108]

Differentiation is integral to the rights and freedoms which the human rights

system seeks to protect. Two categories of non-discriminatory differentiation

protected within a human rights framework are the right to express one’s

cultural identity, referred to variously as minority rights or cultural

rights[109], and the provision of

measures by governments to facilitate the advancement of members of certain

racial groups who historically have been disadvantaged by discriminatory

policies.[110] This latter

category is commonly referred to as special measures – a principle which

has been applied to both native title rights and interests and other Indigenous

land rights.[111] Both the

recognition and protection of distinct cultural rights, and special measures,

are justified by their objective of ensuring the genuine, substantive enjoyment

of common human rights.

The very concept of rights to culture in international human rights

instruments recognises that people enjoy their rights in a culturally specific

way. A classic example of a human right which is culturally specific and

non-discriminatory is native title. The failure to recognise native title before

the Mabo decision in 1992 can be seen, as it was in that case, as the failure to

give equal respect and dignity to the cultural identity of Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples; to be racially discriminatory; and a violation of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s human rights:

Whatever the justification advanced in earlier days for refusing to recognise

the rights and interests in land of the indigenous inhabitants of settled

colonies, an unjust and discriminatory doctrine of that kind can no longer be

accepted. The expectations of the international community accord in this respect

with the contemporary values of the Australian people. The opening up of

international remedies to individuals pursuant to Australia’s accession to

the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights brings to bear on the common law the powerful influence of the Covenant

and the international standards it imports. The common law does not necessarily

conform with international law, but international law is a legitimate and

important influence on the development of the common law, especially when

international law declares the existence of universal human rights. A common law

doctrine founded on unjust discrimination in the enjoyment of civil and

political rights demands reconsideration. It is contrary both to international

standards and to fundamental values of our common law to entrench a

discriminatory rule which, because of the supposed position on the scale of

social organisation of indigenous inhabitants of a settled colony, denies them a

right to occupy their traditional lands.

The Human Rights Committee has commented that article 27 of the International

Convention on Civil and Political Rights (which encompasses Indigenous

peoples’ right to culture) requires the following:

...article 27 relates to rights whose protection imposes specific obligations

on States parties. The protection of these rights is directed to ensure the

survival and continued development of the cultural, religious and social

identity of the minorities concerned, thus enriching the fabric of society as a

whole... States parties, therefore, have an obligation to ensure that the

exercise of these rights is fully protected.

As I have established, the right to give permission and consent is an

expression of cultural rights by Indigenous peoples across Australia.

In order to achieve an outcome that is consistent with Australia’s

human rights obligations, I recommend that the Attorney-General pursue a

consistent legislative protection of the rights to give consent and permission.

A best practice model would be to legislatively protect the right of native

title holders to give their consent to any proposed acquisition.

A second best option would be to reinstate the right to negotiate for all

compulsory acquisitions of native title, including those that take place in a

town or city. That is, amend section 26 of the Native Title Act.

Text Box 1: Full Federal Court decision in Griffiths v Northern Territory

(2007) 243 ALR 72 [112]

In November 2007, the Full Federal Court found that the Ngaliwurru and

Nungali peoples held their native title over the area surrounding Timber Creek

to the exclusion of all others. The decision was significant because it

explained what is required for claimants to prove they hold exclusive possession

native title.

The Court was of the view that:

- It is not a necessary condition of exclusivity that the native title holders

should, in their testimony, frame their claim as some sort of analogue of a

proprietary right. - It is not necessary that the native title claim group should assert a right

to bar entry on the basis that it is ‘their country’. - If control of access to country flows from spiritual necessity, because of

the harm that ‘the country’ will inflict upon unauthorised entrants,

that control can nevertheless support a characterisation of native title as

exclusive. The relationship to country is essentially a ‘spiritual

affair’. - It is also important to bear in mind that traditional law and custom, so far

as it bore upon relationships with persons outside the relevant community at the

time of sovereignty, would have been framed by reference to relations with

Indigenous people. - The question of exclusivity depends upon the ability of the native title

holders to effectively exclude from their country people not of their

community. - If, according to their traditional law and custom, spiritual sanctions are

visited upon unauthorised entrants, and if they are the gatekeepers for the

purpose of preventing such harm and avoiding injury to the country, then the

native title holders have what the common law will recognise as an exclusive

right of possession, use and occupation. - The status of the native title holders as gatekeepers in this case was

reiterated in the evidence of most of the Indigenous witnesses and by the

anthropological report which was ultimately accepted at first instance. - It is not necessary to exclusivity that the native title holders require

permission for entry onto their country on every occasion that a stranger

enters, provided that the stranger has been properly introduced to country by

them in the first place. - Exclusivity is not negatived by a general practice of permitting access to

properly introduced

outsiders.[113]

The

Court concluded that ‘the appellants, taken as a community, had exclusive

possession, use and occupation of the application

area.’[114]

5 Blue Mud Bay – Northern Territory v Arnhem

Land Aboriginal Land Trust

In my Native Title Report 2007, I summarised the Full Federal Court

decision in Blue Mud Bay.[115] In

that case, the court held that the Traditional Owners of Aboriginal land granted

under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) have

the right to control access to, and use of, the tidal areas that are part

of their land. The Northern Territory Government and others appealed the

decision to the High Court.

On 30 July 2008, the High Court held that the Fisheries Act (NT) did

not authorise or permit entry for fishing on Aboriginal

land.[116] The result is that in

order to fish in intertidal waters (both coastline and river mouths) on

Aboriginal land, an outsider needs the permission of the Traditional

Owners[117].

The case, which applies to all Northern Territory Aboriginal

land[118], starkly contrasts with

recent native title cases which have shown the extraordinarily difficult process

that each claimant group must go through to have any native title right and

interest recognised, let alone a right or interest which allows the claimants to

control the use of and access to their land or waters.

However the case was not easily won. Djambawa Marawilli, one of the

Traditional Owners said:

Our struggle was almost for 20 years. Now we had this right now. We had

rights since 2000 years ago. Today it's been given to us in the eyes of most

Australian people.[119]

That struggle was finally won and the Blue Mud Bay case, applying to 80% of

the coastline in the Northern Territory, is the most significant land rights

case in Australia for many years. It will have broader implications however, and

will pressure other governments to similarly realise the rights of their

Indigenous populations.

The Blue Mud Bay decision from the High Court stands as one of the most

significant affirmations of Indigenous legal rights in recent Australian history

... The High Court’s decision gives Australia the opportunity, belatedly,

to catch up with Canada and New Zealand in building co-operative structures

between government, business and Indigenous peoples in commercial

fisheries...[120]

I congratulate the Traditional Owners and the Northern Land Council for their

dedication over the past decades to have the Australian legal system recognise

rights that they always knew were theirs.

5.1 The case

In 1980 the Governor-General, under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern

Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (the ALRA), granted two areas of land to the

Arnhem Land Aboriginal Land

Trust.[121] The land is

inalienable freehold which is held by the land trust for the benefit of the

Traditional Owners. The land grants cover areas on the mainland and islands, and

all grants extend to the low water

mark.[122]

The Traditional Owners of the land, which covers part of North East Arnhem

Land including Blue Mud Bay, sought to clarify whether the Northern Territory Fisheries Act meant that the Northern Territory Government had the power

to grant another person a licence to fish in waters that were within the

boundaries of Aboriginal land. The High Court considered the central issue:

[as] whether, without permission from the Land Trust, a person holding a

licence under the Fisheries Act can fish in the intertidal zone within the

boundaries of either the Mainland Grant or the Islands Grant, or in the tidal

waters within those boundaries. [123]

The main joint judgment considered the following.

- Does the common law public right to fish apply? The court took note of

earlier High Court authority that because the ‘common law right of fishing

in the sea and in tidal navigable rivers is “a public not a proprietary

right, [it] is freely amenable to abrogation or regulation by a competent

legislature”’[124]. On

this basis, the court looked to the Fisheries Act to see whether that

common law right had been abrogated and found that it

had.[125] - Does the Fisheries Act provide that a person may enter and fish in

waters that lie within Aboriginal land? The court found that ‘[n]either

the licence itself nor any provision of the Fisheries Act confers any

permission upon the holder to enter any particular place or area for the purpose

of fishing...the Fisheries Act does not deal with where persons may fish.

Rather, the Fisheries Act provides for where persons may not fish.’[126] - Does the ALRA, and the grants made under it, permit the Land Trust to

exclude persons who hold a licence under the Fisheries Act from entering

waters that lie within the boundaries of the

grants?[127] The court found that

the grants made under the ALRA relate to defined geographical areas (as opposed

to only the dry land or soil within those areas). The provisions of the ALRA

that allow the Land Trust to control entry apply to the whole area within those

boundaries and those boundaries extend to the low water mark. They

considered:The asserted distinction between dry land and the land

in the intertidal zone when covered by water should not be drawn. [128]

In conclusion, the court ordered that: