Native Title Report 2008 - Chapter 2

Native Title Report 2008

Chapter 2

Changes to the native title system – one year on

![]() Download in PDF

Download in PDF

![]() Download in Word

Download in Word

- 1 General observations about the 2007 changes

- 2 Changes to the claims resolution process

- 3 Changes to native title representative bodies

- 4 Changes to respondent funding

- 5 Changes to prescribed bodies corporate

- 6 The CATSI Act 2006

- 7 Improving native title – as simple as an attitude change?

In my Native Title Report 2007, I reported on the changes that were

made to the native title system during that year. The changes, which were made

through two pieces of legislation which amended the Native Title Act, primarily

affected:

- the claims resolution process, including the powers of the National Native

Title Tribunal (the NNTT or the Tribunal), the Federal Court of Australia, and

the relationship between the two - native title representative bodies

- prescribed bodies corporate (through the introduction of the Corporations

(Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006) - respondent funding.

A range of other changes were also made

under the heading ‘technical amendments’.

In the Native Title Report 2007, I expressed concern about how these

changes will impact on the realisation of human rights of Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples.[1] In

particular I was, and I remain, concerned that recognition and protection of

native title was not placed at the centre of the government’s

‘reform’ agenda. Instead, the changes were directed at achieving a

more efficient and effective native title system.

Indigenous people also want a native title system that functions well, but

the version of ‘efficiency’ promoted in the amendments may not

promote the realisation of Indigenous peoples’ rights and legitimate

aspirations. These rights should be at the centre of any dialogue around the

operation of the native title system.

Unfortunately, the Attorney-General has indicated that he does not plan to

review the implementation of the

changes.[2] It is disappointing that,

once again, the impact that the government’s system has on Indigenous

peoples will not be comprehensively or formally evaluated and considered.

In preparing this report, I asked a number of stakeholders for their opinions

on how the changes have impacted on the system. One year on, the changes have

not had a notable impact. A number of stakeholders consider it too early to

tell, and that it may take a while for the changes to ‘filter through the

system’.[3]

In addition, many stakeholders are still not fully aware of the breadth or

detail of the changes. In the beginning of 2008, the NNTT undertook its client

satisfaction research. This survey found that very few respondents were

‘spontaneously aware’ of the

changes.[4] Once prompted, a total of

72 percent of the survey respondents were aware of the reforms. The majority of

the respondents considered that the changes would result in varying degrees of

improved efficiency. Overall however, many ‘were unsure of the real impact

or of the specific nature of these

changes’.[5]

Nevertheless, some observations about the changes can be made. From the input

I have received, it is clear that many stakeholders consider that the changes do

not go far enough to ensure the realisation of Indigenous peoples’ rights,

and if the Native Title Act is going to have the outcomes envisaged in its

preamble, the Australian Government will need to do much more than tinker with

the edges of the system.

1 General observations about the 2007 changes

State and territory governments were generally lukewarm about the impact of

the changes to date.[6] Many

governments voiced uncertainty about whether the changes will result in any

marked improvement. One government stated that the changes ‘had no

discernible impact’ and that so far they ‘do not appear to have

resulted in improvements to the efficiency or effectiveness of the

system’.[7] Others considered it

too early to comment in detail, but reported that it was difficult to say

whether there will be any impact as the new powers of the NNTT have not yet been

exercised, and some other changes have not been

implemented.[8]

Some governments were slightly more positive that the changes will result in

improvements in the future. Victoria’s Attorney-General stated that some

of the changes with regard to the powers of the NNTT will contribute to

‘more efficient and effective mediation of

matters’.[9] Similarly, South

Australia’s Attorney-General commented that ‘to some degree the

amendments have improved the efficiency and effectiveness of the

system.’[10]

Native Title Representative Bodies’

(NTRBs)[11] views are consistent

with those of the state and territory governments. While one NTRB reported that

the amendments ‘have not to date had very much practical effect on [their]

operations’[12], they did

state that they have ‘generally been

positive’[13]. Another

expressed uncertainty about whether the legislative reforms had achieved their

purpose.[14]

The Prescribed Bodies Corporate (PBC) representatives that I spoke to found

it difficult to comment on the impact of the changes, as some of the changes

have not yet been implemented. One PBC commented that ‘there’s been

no discernible

difference’.[15] The most

common PBC comment was that funding and support is their most pressing concern,

which continues to threaten their future operation and their ability to comply

with the changes. One PBC employee from the Torres Strait commented that:

The 2007 changes...it’s very slow coming up in the Torres Strait. We

just got the [Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations] people

starting to do the governance training ... but we’re still finding it

difficult to get funding from the [Torres Strait Regional Authority] for the

individual PBCs.[16]

Observations and feedback I received about specific changes are detailed in

this chapter. In addition, many stakeholders offered their views about what

other areas of the system could be improved and amended in order to better

protect the human rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. I have

outlined some of these suggestions at the end of this chapter.

2 Changes to the claims resolution

process

A major aspect of the 2007 changes dealt with the relationship between the

Federal Court of Australia and the NNTT, and the mediation of native title. The

changes were made in response to a review of the native title claims resolution

process which focused on the more efficient management of native title claims.

The government accepted most of the review’s recommendations and adopted

the option for institutional reform which provides the NNTT with an exclusive

mediation role, in which the Federal Court can intervene at any

time.[17]

Overall, many stakeholders were not inclined to provide positive feedback on

the changes that were made. There is a continuing lack of faith in the

NNTT’s capacity to mediate claims effectively and in the Tribunal’s

and the Court’s ability to work together for the benefit of the system. I

raised concerns about increasing the NNTT’s mediation powers in the Native Title Report 2007.

2.1 Relationship between the NNTT

and the Federal Court

(a) Administrative changes aimed at improving

communication between the NNTT and the Federal Court

The NNTT and the Federal Court have continued and expanded on initiatives

that were started in order to improve the communication between the two bodies.

The President of the NNTT stated that:

Around the country the Tribunal has been more consistent and comprehensive in

[its] regional planning... We are reporting the progress, or lack of progress,

and the reasons why to the Court. Some of the Tribunal members and employees are

appearing before the Court on behalf of the Tribunal to improve communications

between the institutions. There has been some resistance to some of these

initiatives in parts of the country, but I am convinced that such rigour is

needed and that transparency and accountability is

important...[18]

The Court has amended the Federal Court Rules to provide for the procedures

necessary to implement a number of the changes. In addition, the Federal Court

Native Title Registrar noted that:

The Court has worked closely with the Tribunal to ensure that its

relationship with the Tribunal is effective in assisting the timely resolution

of native title claims and that practices in the resolution of native title

claims are transparent.[19]

This has included regular liaison meetings between the Court and the NNTT, ad hoc discussions and briefings, joint information sessions on the

legislative reforms, and regular regional review

hearings.[20]

However, most other stakeholders did not comment on whether they have

witnessed any improvement in the relationship between the Court and the NNTT.

One NTRB did state that they have ‘seen very little evidence to the fact

that those legislative reforms have delivered [enhanced communication between

the NNTT and the

Court]’.[21]

(b) Mediation of native title proceedings

– the NNTT’s new powers and functions

As I mentioned above, the changes made in 2007 gave the NNTT exclusive

mediation powers.[22] However, the

Federal Court Native Title Registrar emphasised that:

The reforms to the native title system ... have not changed the underlying

principle that native title determination applications are proceedings in the

Court and that mediation in the [NNTT] is an adjunct to those proceedings and

directed to their prompt

resolution.[23]

In any case, it is difficult to ascertain what the impacts of these changes

will be, as it appears that many of the Tribunal’s new powers are yet to

be used:[24]

... it’s interesting to see that after the Tribunal got the powers, how

many of those powers have they in fact used? That’s going to be the

burning question... whether much transpired from it I think is the question that

needs to be asked.[25]

The Federal Court has confirmed this, indicating to me that it ‘has not

heard any matters in which it has considered the NNTT’s use of its new

mediation powers, for example directing parties to attend or produce

documents.’[26] The powers of

the Tribunal to refer issues of fact and law or the question of whether a party

should cease to be a party to the Court have not been

used.[27]

Additionally, the Court hasn’t heard any matters in which the NNTT has

reported to the Federal Court that a party or its representative did not act in

good faith during mediation.[28] However, the President of the Tribunal stated that ‘[r]eports from some

Tribunal members suggest that the good faith conduct obligation has had a

positive effect on the conduct of some

parties’.[29]

The one new power that the NNTT does appear to be using regularly is its

right to appear before the Federal Court when the Court is considering a matter

currently being mediated by the

NNTT,[30] but there is little

feedback on the impact this has had.

Nonetheless, even though the Tribunal hasn’t used many of its new

powers, it considers:

...early indications are that in some areas parties are engaging in a more

productive fashion in

mediation...[31]

There were mixed responses from stakeholders about the usefulness of the

Tribunal’s new mediation functions. One NTRB relayed to me that it is not

supportive of the NNTT having additional powers and questioned the

Tribunal’s level of mediation

expertise.[32] Similarly, South

Australia’s Attorney-General considers that ‘[i]f the NNTT,

especially, tries to use its new powers to take more control of our state-wide

negotiations, it will become a serious

hindrance.’[33] He views the

impact of the changes to the Tribunal’s mediation powers with some

scepticism:

The changes assume that close management of claims by the Federal Court and

NNTT is desirable and helpful. Under [South Australia’s] approach, and any

approach that tries to reach broader settlements that incorporate non-native

title benefits, this is questionable. The court and NNTT tend to be impatient

with long periods taken to negotiate settlements, as their statutory role is

resolving applications for determination of native

title.[34]

This view is consistent with the Federal Court’s observations that:

There have, however, been a number of instances ... where parties have

requested that matters not be referred to the NNTT for mediation as other

strategies are being

pursued...[35]

The integral role of mediation and the relationship between the two key

administrative bodies in the system in resolving native title issues was

acknowledged by the Claims Resolution Review and the consequent changes that

were made to the native title system in 2007. Nonetheless, the Tribunal’s

new powers haven’t been used to make any significant change to the system,

and one year later, very little improvement can be seen. The concerns I raised

in the Native Title Report 2007 remain, and I am not optimistic that

without further change, any significant improvement in native title claims

resolution will be forthcoming.

2.2 Registration test

amendments

In my Native Title Report 2007, I noted that new provisions had been

inserted into the Native Title Act, enabling the Federal Court to dismiss

applications that do not meet the merit conditions of the registration test

(which are set out in s 190B of the Native Title

Act).[36] I also noted other changes

to the application of the registration test, including that it must now be

applied to applications that had not previously been subject to the test, it

must be reapplied to those applications that had previously failed the test, and

it does not have to be reapplied in limited situations where a registered claim

is amended.[37]

Between 1 July 2007 and 30 June 2008, the Native Title Registrar made 104

registration decisions. A total of 23 applications were

registered[38], 81 were not

accepted:

The high failure rate reflects the large number of claims that had to be

re-tested under the [2007] amendments... The majority of the claims had

previously failed the registration test, were not on the Register of Native

Title Claims and were not amended following the commencement of the transitional

provisions. The registration test status quo was maintained for many claims (ie

they were not on the Register when the decision was made, and so the native

title claim group did not lose procedural

rights).[39]

Generally the amendments to registration testing have been seen as quite

positive. Victoria’s Attorney-General stated that ‘[i]t may be that

the new powers of the Federal Court to dismiss...applications that have not been

able to pass the registration test, may have some benefits in efficiencies of

the State’s resource

commitments.’[40]

NTRBs have also supported this change as it will allow them to concentrate

their resources better:

...in our area, a number of the early claims...were deficient...by putting

some of the claims through that process again actually did bring to light how

deficient they were and as a result are in the process of being struck out. So

even though, superficially it might sound like a hard provision, it was

necessary... it was a trigger to open up claims and show they were properly

constituted, and properly

authorised...[41]

Other NTRBs have commented that the ability to make minor changes to the

claim and not go through the registration test again is an improvement to the

system that resulted from the 2007

changes.[42]

However, very real concerns have been raised with me about the possibility

that the amendments could limit the rights of Indigenous claimants if the powers

aren’t used with caution:

[The court’s power to dismiss unregistered claims] may be helpful in

dealing with unsustainable claims and paving the way for viable new claims,

although this will depend to a large extent on how the court applies the new

provisions... Dismissals need to be dealt with on a case by case basis with

NTRBs being afforded sufficient time and due process to ensure a claim group has

exhausted all avenues to satisfy the registration test or to demonstrate other

reasons why a particular unregistered claim should not be

dismissed.[43]

Given the serious consequences that can eventuate if a claim is dismissed, I

recommend that the Attorney-General work with NTRBs to monitor the use of the

Court’s powers in order to determine whether the provisions need to be

amended to better protect the important procedural rights for claimants that

come with registration of their claim.

(a) Merit conditions of the registration

test

In the Native Title Report 2007, I outlined my concern that the

interpretation given to section 190B (the merit conditions of the registration

test) by delegates of the Native Title Registrar has varied over

time.[44] Given that the 2007

changes allow the Court to dismiss claims if they fail the registration test

under s 190B, its application by the Registrar is considerably more important -

failure to pass the registration test has even more significant implications

than before.

Last year there was an opportunity for the Federal Court to provide more

clarity on the application of s 190B. Instead, what applicants need to do to

pass the test is more ambiguous and less settled than before.

In August 2007, the Federal Court handed down its decision in Gudjala

People 2 v Native Title

Registrar[45] (the Gudjala

decision), which concerned an application for review of a decision not to accept

an application for registration.[46] The case was dismissed, but in handing down the decision Justice Dowsett set out

detailed requirements for what was necessary to pass the registration test. Many

of these requirements appear to be significantly more stringent than the

requirements were previously thought to be.

For example, Justice Dowsett held that in order to meet the requirement in

section 190B(5)(a) of the Native Title

Act[47], it is not sufficient to

show that all members of the claim group are descended from people who had an

association with the claim area at the time of European settlement, and that

some members of the claim group are presently associated with the claim area. He

considered that the application must address the history of the association

since European settlement, and must provide evidence that the claim group as a

whole, not just some of its members, are presently associated with the

area.[48]

In April 2008, the National Native Title Tribunal released a guide to

understanding the registration

test.[49] It was designed ‘to

assist in preparing a new application for a determination of native title (a

claimant application), or amending an existing

application’.[50] It appears

to follow the more stringent requirements outlined in the Gudjala decision.

However, in August 2008 the Full Federal Court allowed an appeal from the

Gudjula first instance decision, and the matter was remitted to the primary

judge.[51] One of the reasons for

allowing the appeal was that Justice Dowsett ‘applied to his consideration

of the application a more onerous standard than the [Native Title Act]

requires’.[52]

The Full Federal Court explained:

...it is only necessary for an applicant to give a general description of the

factual basis of the claim and to provide evidence in the affidavit that the

applicant believes the statements in that general description are true. Of

course the general description must be in sufficient detail to enable a genuine

assessment of the application by the Registrar under s 190A and related

sections, and be something more than assertions at a high level of generality.

But what the applicant is not required to do is to provide anything more than a

general description of the factual basis on which the application is based. In

particular, the applicant is not required to provide evidence of the type which,

if furnished in subsequent proceedings, would be required to prove all matters

needed to make out the claim. The applicant is not required to provide evidence

that proves directly or by inference the facts necessary to establish the claim.Turning to the specifics of this case, we think there are observations of the

primary judge in his reasons which suggest that his Honour approached the

material before the Registrar on the basis that it should be evaluated as if it

was evidence furnished in support of the claim. If, in truth, this was the

approach his Honour adopted, then it involved

error...[53]

In response to this decision, the NNTT is currently preparing a new guide to

understanding the registration test.

However in the meantime, there is still – if not more –

uncertainty about what is required for an application to pass the registration

test, and yet the consequences of not passing the test are now even more

significant. It is imperative that greater clarity and consistency in

registration testing is achieved as soon as possible.

3 Changes to native title representative

bodies

The 2007 changes also affected the bodies that represent Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander groups to enable them to gain protection and recognition

of their native title rights. The changes affected NTRBs’ recognition,

their areas, the bodies eligible to be NTRBs, their governance, reporting, and

funding.[54]

3.1 Recognition

periods

The 2007 changes introduced fixed term recognition periods for NTRBs of

between one and six years. In the Native Title Report 2007, I expressed a

number of concerns about the changes including the amount of ministerial

discretion in recognising these bodies, the additional administrative burdens

placed on them, the uncertain position that bodies with short recognition

periods are put in, and the preclusion of judicial review for the

decision.[55]

The Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous

Affairs (FaHCSIA) considers that this change:

has already had a positive impact on service delivery by NTRBs. NTRBs are

much more conscious of the need to perform efficiently and effectively as a

result of this change, and are very much aware that their performance will be

subject to detailed assessment as they approach the end of their recognition

period.[56]

Unfortunately, FaHCSIA did not elaborate on exactly how there has been a

positive impact on service delivery, and how this might have affected the

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that the bodies are established to

represent.

The changes also allow the Minister to withdraw recognition of an NTRB if he

or she is satisfied that the body is not satisfactorily performing its functions

or if there are serious or repeated irregularities in the financial affairs of

the body.[57] FaHCSIA reported that

the Minister has not used this power since the changes were

implemented.[58]

The views of NTRBs on the impact the changes to recognition periods have had

on them differs. The Goldfields Land and Sea Council (GLSC) in Western

Australia, which received recognition for three years, said that this time frame

didn’t allow for significant forward and strategic planning in the

management of their claims.[59] Similarly, Queensland South Native Title Services considers:

The whole idea of one year funding or two year funding is ridiculous ... with

our amalgamation, we have a larger area to look at, if one of the arguments is

to attract and retain professional staff, it’s very very difficult to do

that when you are tied to a one year funding cycle, sure there can be comfort

letters to creditors and comments made to employees, but at the end of the day,

we have a very large program to roll out with the surety of only one year

funding.[60]

On the other hand, the North Queensland Land Council (NQLC), which received a

six year recognition period, said that the changes to the recognition periods

have had a ‘positive impact on the NQLC’. They consider that the

triennial funding allocation allows for better forward planning, and is an

improvement over annual funding submissions, giving them greater certainty than

the previous system.[61]

3.2 Operation areas

The 2007 changes also included amendments that allow the Minister to extend

or vary the area covered by a representative body. Significant changes to

representative body areas were made in Queensland over the year, and came into

effect on 1 July 2008.[62]

Specifically, the Gurang Land Council and the Mount Isa region of the

Carpentaria Land Council have amalgamated with the Queensland South Native Title

Services. The Central Queensland Land Council has amalgamated with the NQLC.

These considerable changes have consumed many of the Queensland

representative bodies’ resources and capacity throughout the year. It has

diverted the bodies’ efforts away from progressing native title claims,

and undermined their ability to represent their Indigenous constituents while

they deal with significant change in an under resourced environment.

The NQLC outlined the process undertaken in its amalgamation with Central

Queensland Land Council. In the process, a number of problems were encountered.

NQLC considers that there was a:

...lack of a coherent forward strategy by FaHCSIA in their rolling out of the

Minister’s decisions in this regard. They have been reactive about

responding to challenges that have occurred during the realignment of boundary

process rather than anticipating potential blockages and having strategies in

place to deal with them.[63]

NQLC informs me that FaHCSIA:

...declared to all that there would be ‘business as usual’ at

land councils affected by the boundary changes in Queensland. This is clearly

nonsense as both organisations normal activities were interrupted leading up to

the realignment on the 1st July

2008.[64]

Queensland South Native Title Services, which is the body that now represents

an area previously covered by three NTRBs, relayed similar concerns about how

the amalgamations were undertaken and the impact that it will have on

claims:

...it is a very large area with entrenched issues, different issues, large

land mass, lots of underlying interests, lots of overlaps, to think that within

a very short time frame you could actually effectively amalgamate or expand the

Queensland South boundaries and just flick the switch on the 1st July

and everything would be hunky dorey is an exercise in naivety... there was

compelling logic behind the amalgamation but it was the planning and

implementation that was flawed. FaHCSIA knew what their program was, but they

didn’t engage change agents on the ground... it was very difficult to do

with limited money and resources. Having regard to the enormity of the task and

implications for a significant number of traditional owners, the actual change

process, the timing, and the resources weren’t really thought through as

well as they should have been.[65]

FaHCSIA provided some additional funding for one financial year to assist

with the transition, but there has been no general increase in the annual

budget. Yet both organisations had to perform significant additional activities,

which have impacted directly on the Indigenous people they represent. For

example, the bodies have to get across all the claims, from regions they

previously didn’t cover, quickly enough to address court orders and ensure

the claims aren’t struck out by the Court for a failure to comply with the

orders.

In addition, the bodies have had to undertake consultations with members of

all the claims about future arrangements requiring extensive, and expensive,

community consultations and meetings, which the additional funding was hardly

sufficient to cover.[66]

Consequently, the amalgamations have consumed a significant proportion of the

already scant resources available to representative bodies and that is

impacting, and will continue to impact, upon the native title system across

Queensland. In the end, the people who will bear the cost of the amalgamations

are native title claimants, whose claims have potentially been jeopardised or

put on hold, once again delaying recognition of their rights in the land.

I recommend the Attorney-General closely monitor the impact of the

amalgamations on the operation of the relevant NTRBs, and ensure that FaHCSIA is

providing the direction, assistance and resources they need to transition to

larger bodies.

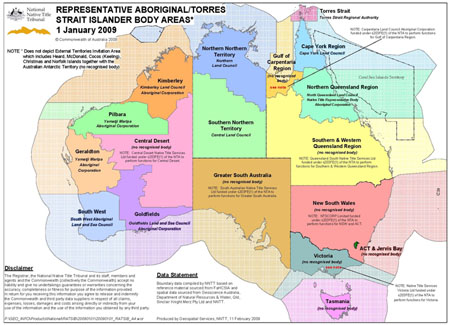

Map 1: Representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander Body Areas

1 July 2008

4 Changes to respondent funding

In 2007, changes were made to the respondent funding scheme. Under this

scheme, the Attorney-General can grant legal or financial assistance to certain

non-claimant parties to enable them to participate in native title proceedings.

The number of parties to any legal proceeding will necessarily increase the

complexity, length, and expense of proceedings for all parties involved. However

in native title proceedings, various parties who do not have a legal interest at

risk in the proceeding can have standing to participate. The numbers of this

type of respondent can reach over one hundred for one claim, seriously hampering

its progress. Sometimes, the parties’ participation is funded by the

Attorney-General under the respondent funding scheme.

The 2007 changes were welcome, and have consequently been well received by

various stakeholders. Both NTRBs and some governments have indicated that one of

the major benefits of the 2007 changes were those made to the respondent funding

scheme: [67]

...[T]he provisions there were to allow a bit more rigour, and that’s a

good thing. When you have a plethora of respondent parties, if you’re

going to get a consent determination, then you have to get the consent of

everyone. If there’s a proliferation of parties because of a relaxed

Federal Court Rule allowing anyone with an interest to become a respondent, and

then there’s eligibility to respondent funding, it behoves an organisation

not to actually mediate a negotiated outcome, it almost perpetuates itself to

ensure there is no mediated outcome. So I think that was a good thing, but

again, has there been an overall reduction in respondent funding, has it reduced

the number of parties, has it made it a disincentive to be a party, I

don’t know.[68]

The expenditure on the scheme has indeed been reduced, implying that the

Attorney-General is considering the impact of these parties on native title

claimants and proceedings. Expenditure for the respondent funding scheme fell

from $5.01 million in 2006-07 to $4.25 million in 2007-08. This reduction in

spending has been attributed to the 2007 changes which encourage agreement

making and ‘considerably limit assistance available to non-government

respondents for court

proceedings’.[69]

However, many of the concerns I raised in the Native Title Report 2007 have not been addressed or responded to by the Attorney-General. In summary, I

am concerned that there is no information about how the scheme has been

evaluated and no specific effort by the Attorney-General to determine how the

funded parties impact on the proceedings or the native title rights and

interests of Indigenous peoples. The Attorney-General has indicated to me that

his assessment of the conduct of parties who are funded under this scheme,

‘to a large degree’ follows the lead of the Federal Court, NNTT and

other parties.[70] In other words,

the impact of these parties on the proceedings is not known. Perpetuating my

concern is the fact that the details of which parties are being funded is

confidential. Consequently, no one is able to hold the government accountable

for how these public funds are being spent.

I encourage the Attorney-General to consider the recommendations I made in

chapter 4 of the Native Title Report 2007 to further improve the

respondent funding scheme.

5 Changes to prescribed bodies

corporate

Prescribed Bodies Corporate (PBCs) are essential to native title. They are

the bodies that are established to hold native title on trust or as an agent for

the native title holders. Their primary role is to protect and manage determined

native title in accordance with the native title holders’ wishes and

provide a legal entity through which the native title holders can conduct

business with others who are interested in accessing their land or waters. They

are integral to the system and to achieving the broader outcomes from native

title that communities and governments want to see:

PBCs are critical organisations that are going to have to deliver during

outcomes from the native title process for native title holders and the wider

Australian community, and the Government needs to fully understand and properly

support this.[71]

Some of the changes made to the native title system in 2007 were intended to

address a number of the problems PBCs face in order to operate. However, the

changes are not sufficient to support the effective operation of PBCs. It is

positive that the government has acknowledged the significance of these bodies

and has committed to funding them appropriately on many

occasions.[72] I look forward to

seeing how PBCs will be funded as an outcome from the government’s review

of funding of the native title system that will feed into the next federal

Budget.

However, in the meantime, the role of PBCs is in jeopardy because of the poor

level of support available for them and the role that they are expected to play

in the community. Pila Nguru, a PBC based in the Tjuntjuntjara Community in

Western Australia, highlights the difficult role that PBCs play:

Walking the line between upholding traditional responsibilities and making

moves to secure a future for remote community can be tricky...I cannot see it is

in anybody’s interests to have PBCs collapse but I cannot equally see how

they can continue without at least a skeletal funding

base.[73]

5.1 Financial support

As I have indicated, one of the most pressing concerns of PBCs is support for

their operation; both financial and non-financial. The necessity of federal

support for PBCs is strongly endorsed by state and territory

governments.[74]

The 2007 changes allowed for some additional mechanisms through which PBCs

could gain support from the federal government, either directly through FaHCSIA

or through NTRBs.[75] However,

FaHCSIA have stated that:

In terms of the 2007 policy change to permit the provision of funding support

for PBCs beyond their initial establishment phase, we have been limited to the

extent to which we have been able to assist PBCs by the level of resources

available to the program. The high level of demand for resources by NTRBs has

made it difficult to secure funds for PBC support within existing

funding...[76]

At the end of June 2008, there were 57 Registered PBCs (known as Registered

Native Title Bodies Corporate) on the National Native Title Register. A further

12 determinations of native title are awaiting a determination of a Prescribed

Body Corporate to become the Registered Native Title Body

Corporate.[77] Of these, only ten

received funding from the federal government, to a cumulative total of $380,000

which was sourced from funds allocated to

NTRBs.[78]

Although the establishment of a PBC is a requirement of the Native Title Act

once a determination is made, the federal government has stated that it should

‘not necessarily be considered a first stop for funding. Funding should

also be sought as appropriate from state and territory governments and agencies,

industry and other relevant Australian Government departments and

agencies.’[79]

With limited government money available, funding is becoming an increasingly

urgent concern. In addition, as the native title system progresses, the number

of PBCs in the country is rising, and the focus of native title policy is to

some extent moving from interpretation of the Native Title Act to implementation

of the rights granted. However, implementation and realisation of native title

rights are stifled, and can even be extinguished and lost when the PBC cannot

operate effectively.

So where can PBCs obtain funding? Because of the nature of native title

rights and interests, PBCs can very rarely use native title to make a profit

which would support their sustainability. However, where a claim group has

managed to negotiate monetary or other benefits through an Indigenous Land Use

Agreement or broader settlement, this may include provision for funding the PBC.

But this funding typically comes from private interests, which is not consistent

across Australia, or is an optional extra from state or territory

governments.[80] As a result, there

is nothing at all in the system which guarantees PBCs’ viability, and

therefore there is nothing in the system which guarantees that hard won

recognition of native title rights will be effective into the future.

I recommend that the Attorney-General significantly increase financial

support for PBCs as a separate funding base from that allocated for NTRBs. At a

minimum, PBCs should be allocated a specific funding grant for the first year of

the PBC’s operation, to ensure it is established in accordance with the

significant regulations that apply to them.

A related issue that has been raised with me is that some native title

claimants are forming corporations through which they utilise the procedural

rights afforded under the Native Title Act, and carry out other dealings with

the land before a native title determination has been made. As these bodies are

not yet PBCs under the law (as there is no determination of native title), there

is no funding available through the Commonwealth for these corporations at all.

Yet they are also essential to the system’s operation and the protection

of native title rights and interests prior to a determination. A determination

itself will take many years if it is even sought. However, if a broader

settlement is achieved (and the focus of significant stakeholders is shifting in

this direction), a native title determination may never be made, and these

corporations will have immense difficulty surviving and protecting their rights.

Currently, many of these organisations are operating via the goodwill and pooled

resources of a claim group, while the individuals who run it are stretched to

their limit, simultaneously continuing with other paid employment and fulfilling

their family and community commitments.

Additionally, both the Attorney-General and the Minister for Indigenous

Affairs have emphasised the need for native title agreements to result in

broader outcomes for Indigenous communities. It is PBCs that will be the

organisations that must implement these agreements and ensure those outcomes are

attained. They are the vehicle that will be used to achieve a range of social,

cultural, political and economic

aspirations.[81]

When the government considers the level of support it will provide for PBCs,

it should consider the broader roles that PBCs play in achieving and protecting

Indigenous peoples’ rights to their land, and attaining broader benefits

for communities.

5.2 Fee for service

One of the 2007 changes did provide a potential funding source for PBCs by

allowing them to charge a third party to a negotiation for costs and

disbursements reasonably incurred in performing statutory functions. However,

the provisions only commenced on 1 July 2008, and the PBCs that I received

feedback from did not comment on whether they intend on using the provisions.

FaHCSIA is also uncertain about whether the new power has been utilised or how

much impact it will have:

The capacity to charge fees for costs incurred in undertaking negotiation of

agreements etc ... is likely to have had some impact but we do not have

sufficient information on the extent to which it has been applied in

practice.[82]

I raised concerns about how this scheme will operate in the Native Title

Report 2007[83], and I encourage

the Attorney-General to monitor the new powers to identify how and to what

extent they assist or hinder PBCs to obtain funds.

5.3 PBC Regulations

A number of the 2007 changes affecting PBCs have not been implemented. Many

of the changes that were announced require the Native Title (Prescribed

Bodies Corporate) Regulations 1999 (the PBC regulations) to be amended

before they have any effect. These amendments relate to a host of changes to

PBCs that were decided on, including PBC consultation requirements, standing

authorisations, default PBCs, replacement PBCs and a raft of other

issues.[84]

In the Native Title Report 2007, I raised a number of issues that

should be considered when drafting these amendments. I recommend the

Attorney-General and the Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and

Indigenous Affairs consider these while they draft the regulations, and consult

widely with PBCs, NTRBs and Indigenous people once a draft is available.

6 The CATSI Act 2006

The Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth) (the CATSI Act) came into effect on 1 July 2007. It provides for the

incorporation and regulation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Corporations, and significantly changes the law that previously governed

Indigenous corporations. The CATSI Act affects the native title system because

PBCs must be incorporated under

it.[85] Once a PBC is incorporated

under this Act, it is registered on the National Native Title Registrar as a

Registered Native Title Body Corporate

(RNTBC[86]).

In the Native Title Report 2007, I summarised the main changes to

Indigenous corporations through the enactment of the CATSI Act, and my concerns

about the impact it will have on the human rights of Indigenous

Australians.[87] I raised the

concern that PBCs will not receive the support and resources they need in order

to comply with the CATSI Act and that, as a result, they risk losing control of

their native title rights and interests, or jeopardising these interests in

other ways.

Because corporations have up until 30 June 2009 to transition their

constitutions to be in line with the new Act, the CATSI Act has not yet been

fully implemented.

Consequently, the corporate regulator, the Office of the Registrar of

Indigenous Corporations (ORIC), has not assessed the impact that the CATSI Act

has had on Indigenous corporations. The Registrar has informed me that

‘[i]f an assessment of the impact of the CATSI Act is to be undertaken, it

will be undertaken after 30 June 2009. What any assessment would include has not

yet been decided’.[88]

The Registrar also noted that:

Feedback on the CATSI Act has been far-reaching and both positive and

negative. There has been no formal assessment of feedback on the CATSI Act to

date and therefore I cannot comment on RNTBCs’ views in this

context.[89]

In the meantime, ORIC has undertaken a number of initiatives such as

producing guidelines, pre-populating some of the reports that PBCs need to

submit to ORIC in order to comply with the reporting requirements, and providing

training.[90]

ORIC has reported that the number of registered PBCs that are not complying

with the reporting and other regulatory requirements has fallen from 49 percent

in October 2007, to 14.8 percent in October 2008. The Registrar considers that

this is probably due to his office’s regular contact with NTRBs, and the

NTRBs’ and ORIC’s support for registered PBCs (including

training).[91]

Encouragingly, the Registrar has also established a planning and research

team which will research non-compliance and why Indigenous corporations go into

administration. I look forward to reading the results and anticipate that they

will be able to be utilised effectively by the Registrar and the government to

benefit Indigenous corporations and assist them to operate independently and

capably.

However, a number of factors remain a concern.

I have received feedback that because the CATSI Act appears to have been

drafted largely with PBCs considered as just another form of corporation, many

of the regulations are not consistent with or complementary to the native title

system. This creates tension and confusion among PBC members:

Certainly I’ve noticed a big change in the compliance aspects of

registration... the CATSI rule book is very complex particularly in the context

of native title... you have to try and combine the two, and then you have to

– other than explain it to people who speak English as a second language

– you then have to have it all amended in accordance with your existing

constitution and so on, it’s actually very resource intense. And

there’s no funding specifically earmarked for this as far as I can tell...

I think administratively the transition under the CATSI Act has really increased

the burden for people that don’t have independent assistance. I think

those groups are going to really struggle to deal with it all because it really

is very complex.The whole problem with ORIC, is that the whole notion of PBCs and native

title entities has been secondary, and almost an afterthought. The whole notion

of contractual membership where you have to get each member to sign something

requesting to become a member, and then having the Board of Directors say yes or

no, seems to be completely out of kilter with the notion of native title groups;

you’re either a member or you’re not in terms of the rules that

apply under traditional law and custom. That’s something that’s been

completely ignored or

overlooked.[92]

I am also concerned that while the law is still being implemented and the

initial impacts are uncertain and mixed, there is no reliable data on why

registered PBCs have been non-compliant with the regulatory requirements to

date, whilst at the same time there is widespread recognition that these bodies

are severely under-funded. Because of this, I recommend that the Registrar and

FaHCSIA together undertake a review of the impact that the CATSI Act has on

Indigenous corporations once implementation of the Act is complete. In

particular, the review should examine the impact of the CATSI Act on PBCs’

ability to protect and utilise their native title rights and interests.

Finally, in order to be able to comply with the regulatory requirements, PBCs

need to have access to funding, resources and skills. The funding available to

them from the government however is, at least in part, dependent on their

capacity to govern themselves. Yet this inter-dependence between funding and

governance has not been sufficiently recognised by government. The Registrar of

Indigenous Corporations informed me that ORIC ‘does not have any role or

influence in determining FaHCSIA funding for

RNTBCs’[93]. This is yet

another example of government departments acting in silos, and I recommend that

FaHCSIA work cooperatively with ORIC to ensure the funding of registered PBCs is

consistent with the aim of building the capacity of these bodies to govern

themselves and operate independently, securing the future and utilising their

native title rights and interests.

7 Improving native title – as simple

as an attitude change?

It is evident that the 2007 changes have not yet had any significant impact

on the native title system. Perhaps it is too early to tell, but a broad range

of stakeholders support my concern that the changes will not deliver the

substantial changes that the system needs. It is doubtful whether the changes

will be of any perceptible benefit to the Traditional Owners of the land, and it

is unlikely the net result will be an increased protection of the human rights

of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

It is disappointing that the government spent a number of years, multiple

reviews and countless resources to simply tinker with a system that is in dire

need of reform. I hope that this trend does not continue, and that the

government now concentrates on actions that will fulfil the commitments it has

made over recent months to improve the system.

As I outlined in chapter 1 of this Report, while the government has

recognised some of the fundamental flaws with the outcomes of native title and

has committed to finding new solutions, the government’s main focus will

be altering the attitude of parties involved in native title:

I share the concerns expressed in the [Native Title Report 2007] about

the outcomes being obtained through the native title system. The heart of the

Native Title Act 1993 is the principle that the recognition of Indigenous

people’s ongoing connection with their land should occur through

negotiation and mediation, not litigation, wherever possible. I have actively

encouraged all parties to take a less technical approach to native title, and to

use the opportunities presented by native title claims to facilitate the

reconciliation process and to negotiate better and broader outcomes for

Indigenous people....

I believe that the key to achieving better outcomes lies in all parties

changing their behaviour and engaging more flexibly, to achieve and build upon

recognition of the ongoing relationship of Indigenous people to the

land.[94]

Although there is benefit in this, I am concerned that this will not be

sufficient, and that this policy needs to be complemented by changes to the

underlying system if the outcomes the government would like to see are to be

attained.

Firstly, ‘attitudes’ to policy are discretionary and dependent on

the elected government for each jurisdiction. It does not create certainty,

predictability or equity in native title outcomes across Australia. If a

government changes, there is no guarantee that the ‘flexible’

approach will be maintained. The markedly different outcome from a simple change

in approach is seen in chapter 3 of this Report, where the Northern Territory

government changed during a compulsory acquisition case.

Improvements to the system need to be enshrined in legislation to ensure that

the rights of Indigenous peoples are always protected, and not swept aside when

it’s convenient.

Secondly, while supporting the flexible and less technical approach to native

title, the Northern Territory (NT) Government has already warned:

[T]he Australian Government’s proposal for broader settlements and

regional initiatives using the native title process may be constrained by the

legal requirements of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and court

processes.[95]

That is, stakeholders consider that there are considerable constraints within

the Native Title Act that may prevent them from making significant progress in

improving the native title outcomes that are

agreed.[96]

Thirdly, I am concerned about the breadth of change that can be achieved when

nearly all of the state and territory governments have indicated to me that they

consider that they have already been acting in a flexible manner for

years.[97] Consequently, they all

naturally support the federal Attorney-General’s approach, but this begs

the question; how much more flexible will these governments be? For example

South Australia’s Attorney-General

indicated:[98]

South Australia supports the Commonwealth’s new emphasis on achieving

broader settlements through less technical and more flexible approaches and has

been implementing that approach for nine years.

Because of these weaknesses, I recommend the government consider further

legislative and policy changes that have been discussed in this, and previous,

native title reports. In addition, the government could consider tying the

announced funding to state and territory governments for native title

compensation payments, to state and territory behaviour in native title

agreement making and the settlement of broader

agreements.[99]

7.1 Further suggestions for

improvement

Throughout this Report, and previous native title reports, I have made a

number of recommendations for improvements that can be made to the native title

system. In addition to these, government agencies, NTRBs and PBCs have offered

me their own suggestions about how the system could be improved. Many of these

are consistent with recommendations in native title reports. I recommend that

the Attorney-General consider these suggestions.

(a) Federal Court’s power over native

title proceedings

Both Victoria’s and South Australia’s Attorneys-General have

indicated a strong preference for the option of ‘long-term

adjournments’ of native title claims at the request of all parties:

One area of reform Victoria believes is worthy of further exploration is the

potential for the State and native title parties to approach the Court and

obtain a ‘suspension’ or ‘long-term adjournment’ of a

claim for a period of time to enable them to negotiate ancillary outcomes ...

The problem sometimes arises where these broader outcomes are not being realised

because of pressure from the Court to resolve the native title question more

quickly. This can lead to missed opportunities for traditional owners, or

ancillary agreements that are difficult to implement because the policy

development behind them was rushed. Preparing for regular court appearances can

divert resources from making progress on negotiating broader

agreements.[100]

Similarly, South Australia’s Attorney-General commented:

...there must be scope to exclude the Federal Court and the NNTT from

involvement where all parties agree that they want to proceed themselves...the

threat of having a trial listed by the Court can also distract parties and

divert resources from negotiations. This is especially so if the parties are

trying to negotiate settlements that include benefits beyond a determination of

native title. Those negotiations necessarily take more time while the Court is,

generally, only interested in native-title

results.[101]

I see the merit in this approach, and support such a proposal if both parties

consent to an adjournment.

(b) Funding and support for Native Title

Representative Bodies and Prescribed Bodies Corporate

Almost every organisation in the native title system has expressed serious

concern about the impact that under-resourcing of NTRBs has on native title

claims. Each state and territory government expressed this concern to me.

Victoria’s Attorney-General identified the need for ‘more robust

and secure funding for NTRBs, including native title service

providers...organisational capacity, expertise and good governance of these

bodies... is critical to the functioning of the native title system as a

whole’. He also stated that the Victorian Government would:

welcome a greater focus on enhancing capacity with respect to the statutory

dispute resolution functions of these bodies, in relation to disputes between

their constituents.[102]

This is a significant problem for Indigenous peoples. Approximately half of

the complaints that FaHCSIA receives about the native title system are about

authorisation or intra-Indigenous

disputes.[103]

Significant work has already been done on approaches to Indigenous

decision-making and dispute management by the Indigenous Facilitation and

Mediation Project (IFaMP).[104] The project, which was undertaken by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), made a number of findings and

recommendations on agreement making through non-adversarial approaches, some of

which were specific recommendations to improve the native title system. The

recommendations included funding and establishing an accredited national network

of Indigenous process experts including mediators, facilitators and negotiators;

the incorporation of Indigenous expertise into native title mediation processes

and support for the development of Indigenous expertise and the development of

specific native title national standards and/ or a code of ethical conduct which

addresses the roles and responsibilities of all

parties.[105] I encourage the

Attorney-General to consider the recommendations made in the final report of the

Project.

Victoria’s Attorney-General also suggested that there should be greater

support for PBCs to carry out the substantial responsibilities that the Federal

legislation imposes on them. He has suggested that a program similar to the

Aurora program be funded for building the capacity of

PBCs.[106] AIATSIS already has a

project underway which is aimed at supporting PBCs to hold and manage their

country ‘through research and participatory planning to support

capacity-building in effective decision making and conflict resolution

processes, frameworks, negotiation skills, agreement making, strategic planning

and governance’[107]. This

project could be further supported by government.

Similarly NSW’s Minister for Lands considers that the Commonwealth

Government:

...should examine further Commonwealth measures of support (both financial

and non-financial) for native title representative bodies and prescribed bodies

corporate.[108]

I have discussed the issue of funding in chapter 1 of this Report and earlier

in this chapter.

(c) Extinguishment of native title

The Queensland Department of Natural Resources and Water would like the

Commonwealth Attorney-General to consider the necessity of the permanency of

extinguishment of native title, and whether the principle of non-extinguishment

can be extended:

The benefits of extending the operation of section 47 suite of the NTA which

sees the disregarding of the extinguishment of native title occurring in certain

circumstances.[109]

Justice Wilcox also thinks that the Attorney-General should re-consider the

permanency of extinguishment:

One change that could be made, and it’s just a great shame that

it’s necessary. The current doctrine is that if there’s ever been

[extinguishment] by the Crown, whether a grant of freehold or a grant of lease,

that terminates native title, even if the land is subsequently reverted to the

Crown...Now why do we have to stick to that rule?...I think that’s an area

that can usefully be looked

at.[110]

I agree that this approach would be beneficial, and would increase the

possible recognition of native title, going some way to mitigating the impact of

colonisation on Indigenous peoples’ rights and interests. It would also be

consistent with the Native Title Act’s preamble that states: ‘where

appropriate, the native title should not be extinguished but revive after a

validated act ceases to have

effect.’[111]

(d) Recognition of traditional ownership

outside the native title system

The Native Title Act was intended to be just one of three complementary

approaches to recognise, and provide some reparation for, the dispossession of

Indigenous peoples’ lands and waters on colonisation. The two other limbs

were to be a social justice package and a land fund that would ensure that those

Indigenous peoples who could not access native title would still be able to

attain some form of justice for their lands being taken away.

It was in this context that the Native Title Act was drafted and passed by

Parliament. However, the other two limbs did not eventuate in the form intended,

and this abyss is one of the underlying reasons why the native title system is

under the strain it is under today.

The social justice package never came to fruition. The new Rudd

Government’s Platform states that it will ‘recognis[e] that a

commitment was made to implement a package of social justice measures in

response to the High Court’s Mabo decision, and will honour this

commitment’.[112] In an

appendix to this Report I have summarised the main recommendations and proposals

for a social justice package that were made at the time by the Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Commission and the former Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Social Justice

Commissioner.[113]

The land fund commitment was realised through the Indigenous Land Corporation

(ILC) which continues to operate today, but does not always provide an effective

and accessible alternative form of land justice when native title is not

available. Consequently, it could not be said to fulfil Australia’s

commitments to land rights, nor fulfil the function it was intended to as was

set out in the preamble to the Native Title Act, which states:

It is also important to recognise that many Aboriginal peoples and Torres

Strait Islanders, because they have been dispossessed of their traditional

lands, will be unable to assert native title rights and interests and that a

special fund needs to be established to assist them to acquire land.

(e) The Indigenous Land Corporation

The Native Title Act as passed in 1993 established a National Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Land Fund. However, a number of changes made since 1993

have meant that this fund, which is referred to now as the Land Account, is

administered by the Indigenous Land Corporation

(ILC).[114]

The Act which now provides the functions of the ILC is the Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Act 2005 (Cth). The preamble to this Act also

acknowledges the need for land justice for Australia’s Indigenous peoples,

but does not draw any connection to native title and the complementary role the

Land Account was supposed to play:

And whereas they have been progressively dispossessed of their lands and this

dispossession occurred largely without compensation, and successive governments

have failed to reach a lasting and equitable agreement with Aboriginal persons

and Torres Strait Islanders concerning the use of their lands...

It is this Act which dictates the ILC’s functions, which primarily

relate to land acquisition and land management. The Act only mentions native

title twice, but never draws on the integral relationship between the Land

Account, the functions of the ILC, and native title.

Recently, I have received an increasing number of inquiries and concerns

about the ILC and the role it is playing in the realisation of land rights and

justice for Indigenous people. Many Aboriginal people and Torres Strait

Islanders are confused about its role, its activities and the outcomes it is

achieving. Indigenous people have indicated to me that they are concerned that

the ILC does not focus enough on reparation for dispossession, but instead is

concerned with economic gain.[115]

Perhaps the link between dispossession and the role of the fund in the

achievement of land justice and the native title system should be considered

further, and the link made more explicit and direct. The Queensland Department

of Natural Resources and Water would support such an approach. It suggests that

the Attorney-General should consider ‘how to increase the role of the

Indigenous Land Fund in the resolution of native title

claims’.[116] I would

support such a review and a consideration by government, in consultation with

the community, of how the ILC’s functions could better complement the

native title system and contribute to the outcomes government would like to see.

In the meantime, the two other social justice limbs referred to in the

preamble to the Native Title Act do not operate in the way originally intended.

Because of these constraints, there has been unforeseen pressure on the native

title system to deliver even though native title was never intended to be the

panacea for dispossession in Australia:

What we need to do is return to the preamble of the Act Where the NTA was

only intended to be part of a broader package to assist in the realisation of

Indigenous land aspirations. When you unpack the box and leave on the NTA, we

all go scurrying towards the very thing that [Justice] Brennan intimated way

back in 1992 in the Mabo judgement that native title was going to be very

difficult to prove. To me, I think the preamble actually spells it out quite

nicely. If you’re going to be looking at these things you’ve got to

look at it comprehensively and we shouldn’t be taking a slavish technical

approach to the extent where for instance we don’t even get a seat at the

negotiation table unless we overcome the demands of full lown connection. We

should only be looking at right people, right country, and some mechanism to

determine that.[117]

Recognising that native title is not producing land justice for the majority

of Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders, there is a discussion

gathering momentum about how traditional ownership can be recognised short of a

native title determination. After hearing a number of native title cases as a

judge in the Federal Court, Justice Wilcox considers this:

What [Traditional Owners] are wanting, what they’re crying out for, is

for the people who represent authority figures to them, and it’s the

government or the courts speaking on behalf of government, I suppose

that’s the way they would see it, to say this is who you are and we

recognise who you are. Now for that reason, I would like to see added to the

Native Title Act, some provision that allows the court, even if not granting

native title, or recognising native title, to determine the particular group are

the people whose ancestors were there at the time of settlement and that

they’ve maintained continuity as a people even if they cant prove

continuity from generation to generation of observing the law... I think until

we recognise that the system that was seen in Mabo, which after all was a remote

island, hardly impacted by white settlement, simply doesn’t work for [most

Indigenous people]. And it’s going to be a source of great disappointment,

even a feeling that they’ve been conned...Here’s the government of

the country and Parliament passing statutes which seem to promise so much and

yet when the claim is brought they just can’t get there and then they get

nothing, not even

recognition...[118]

Justice Wilcox has linked the difficulty of the legal hurdles required to be

jumped for native title, with the gridlock the system is in today, and sees an

alternative form of recognition as one way of dealing with this problem:

What [Traditional Owners] are wanting I think more than anything is

recognition and we could change that quite easily by just adding a new section

to the Act... it wouldn’t be as much satisfaction as actually winning a

native title claim but it would go a long way to at least make an appeal that

they are recognised as who they are.I just find it really difficult to live with the idea that people like the

Yorta Yorta and Larrakia and Noongar people just get kicked out with just

nothing, and there’ll be more cases like that. One of the problems is, one

of the reasons why the native title list is in such a static condition in the

court is I believe that many of the claimants have been advised that the case

will not succeed and go nowhere but they can’t bring themselves, or

persuade those whom they represent perhaps, to just say ok we give up, we

abandon it, because they see that as a being a concession that they’re not

who they are and so we’ve got 500 cases waiting in the list and

there’s hardly any movement in the list.I had a lot to do with the native title list and I just about went crazy

trying to get cases up to the barrier and you couldn’t and for a whole

host of reasons, it wasn’t justice but I think many of these cases they

ought to be. Normally with any other litigation say, well this has been here for

a long time and I’m going to set a date and it’s going to go on that

day. But you know that if they did that they’d probably just discontinue

the claim ... or you’d come to the courts and you’d force them onto

the situation where the whole thing is a mess... they’ve probably been

told, look don’t bring it on, you’re not going to get anywhere. And

yet they can’t say this is hopeless. They’re wanting the court to

say you are who you are.[119]

Similarly, the Queensland government would like the Attorney-General to

consider:

The establishment of a ‘traditional owner’ status under the NTA

which could be by way of an extension of the claim registration process with the

NNTT responsible for the recognition of the status. The status could carry with

it a suite of benefits.[120]

These ideas are closely connected to the limitations on the ILC’s

operation and its consequent inability to comprehensively fulfil the objectives

that a native title land fund was intended to deliver. It is essential that this

void is filled, be it through review of the ILC’s role or amendments to

the Native Title Act to provide an alternative form of recognition when native

title is not available.

Recommendations

- 2.1 That any further review or amendment that the Australian Government

undertakes to the native title system be done with a view to how the changes

could impact on the realisation of human rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples.

- 2.2 That the Australian Government respond to the recommendations made in

the Native Title Report 2007 on the 2007 changes to the native title

system.

- 2.3 That the Australian Government and the National Native Title Tribunal

draft a comprehensive and clear guide to the registration test. The Australian

Government should consider whether further guidance on the registration test

should be included in the law, through regulation or through amendment to the

Native Title Act.

- 2.4 That the Australian Government monitor the impact of the Queensland NTRB

amalgamations on the bodies’ operation, and provide direction, assistance

and resources to those bodies which require it.

- 2.5 That the Australian Government create a separate funding stream

specifically for Prescribed Bodies Corporate and corporations which are

utilising the procedural rights afforded under the Native Title Act.

- 2.6 That once the CATSI Act has been implemented, the Registrar of

Indigenous Corporations and the Minister for Families, Housing, Community

Services and Indigenous Affairs, together review the impact the law has on

Indigenous corporations. In particular, the review should examine the impact of

the CATSI Act on PBCs’ ability to protect and utilise their native title

rights and interests.

- 2.7 That the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations and the Minister for

Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, work closely to

ensure that funding provided to registered PBCs is consistent with the aim of

building PBCs’ capacity to operate.

[1] T Calma, Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Native Title Report 2007,

Australian Human Rights Commission (2008), pp 24-27. At: http://www.humanrights.gov.au/social_justice/nt_report/ntreport07/index.html.

[2] R McClelland,

Attorney-General, Correspondence to T Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Australian Human Rights Commission, 11

September 2008.

[3] G Roche,

Manager, Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous

Affairs, Correspondence to T Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social

Justice Commissioner, Australian Human Rights Commission, 11 September 2008; G

Neate, President, National Native Title Tribunal, Correspondence to T Calma,

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Australian

Human Rights Commission, 27 August 2008.

[4] The survey was completed by

213 individuals and organisations that have had contact with the Tribunal since

its inception: see G Neate, President, National Native Title Tribunal,

Correspondence to T Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice

Commissioner, Australian Human Rights Commission, 5 August 2008, p 10. Based on

spontaneous awareness, changes to mediation (15%) and the registration test

(14%) were the best known, no other was mentioned by over 10% of the total: see

G Neate, President, National Native Title Tribunal, Correspondence to T Calma,

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Australian

Human Rights Commission, 5 August 2008, p 2.

[5] G Neate, President, National

Native Title Tribunal, Correspondence to T Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Australian Human Rights Commission, 5

August 2008, pp 1-2.

[6] The

government of Western Australia was the only government that I did not receive

input for the Report from. The Western Australian Government was in caretaker

mode when I was collecting information for this Report.

[7] M Scrymgour, Northern

Territory Minister for Indigenous Policy, Correspondence to T Calma, Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Australian Human Rights

Commission, 18 September 2008.

[8] J McNamara, Executive Director, Indigenous Services, QLD Department of Natural

Resources and Water, Correspondence to T Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Australian Human Rights Commission, 18

September 2008; R Hulls, Attorney-General of Victoria, Correspondence to T

Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner,

Australian Human Rights Commission, 16 September 2008.

[9] R Hulls, Attorney-General of

Victoria, Correspondence to T Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Social Justice Commissioner, Australian Human Rights Commission, 16 September

2008.

[10] M Atkinson,

Attorney-General of South Australia, Correspondence to T Calma, Aboriginal and