Report: Visit of the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women

Foreword

In 1994, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights appointed a Special Rapporteur on violence against women, including its causes and consequences. The mandate was extended by the Commission on Human Rights in 2003, at its 59th session in a resolution that, inter alia, affirmed that violence against women constitutes a violation of the human rights and fundamental freedoms of women and impairs or nullifies their enjoyment of those rights and freedoms. Almost twenty years later, in April 2012, the current UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, including its causes and consequences, Ms Rashida Manjoo, accepted an invitation to conduct a study tour to Australia. This was the first visit to Australia ever undertaken by the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women.

The study tour represented an important opportunity for governments, community organisations and individual women across the country to consider the manifestations of violence against women within Australia, and review the strategies being used to reduce and eliminate all forms of violence against women and its causes. Importantly, the tour took place against the backdrop of Australia’s National Action Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and Their Children, launched in 2011. Discussions with study tour participants – particularly with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, migrant and refugee women, women with disability and women of diverse sex, sexuality and/or gender – allowed for an important initial assessment of the National Plan and its desired outcomes and signalled a strong need for its rigorous and comprehensive implementation, with the full support of governments across all jurisdictions.

Whilst not a formal mission, the study tour gave visibility to a pressing, and often silent and invisible, human rights crisis within Australia. It brought together victims and survivors of violence who boldly demonstrated the pervasive nature of violence, its various forms and its impact on individual lives, families, communities and society at large. The study tour also highlighted the extraordinary range of significant work being undertaken by women and men, NGOs, government departments and various service providers to reduce and eliminate the causes and consequences of violence against women.

This report aims to provide an overview of the study tour and capture the key issues raised throughout discussions. It seeks to identify best practice and those areas which require additional analysis and attention.

We greatly appreciate hearing the testimony of extraordinary women who worked with us and participated in the tour. We would also like to thank the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs for funding and enabling the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, Ms Rashida Manjoo, to visit Australia and all of the government and community organisations who generously assisted in bringing together these various roundtables and other forums, discussions and site visits within a very short timeframe. Your contribution was invaluable to the success of the tour.

Elizabeth Broderick

Sex Discrimination Commissioner

Andrea Durbach

Former Deputy Sex Discrimination Commissioner

Executive summary

From 10-20 April 2012, the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, including its causes and consequences, Ms Rashida Manjoo, undertook a study tour in Australia.1

The study tour was co-hosted by the Australian Human Rights Commission and the Australian Government (Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA)).

The objectives of the study tour included:

- gathering information on violence against women, its causes and consequences, from government and non-governmental organisations, including women's organisations;

- gathering information on culture and violence against women in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities; and

- identifying strategies to eliminate all forms of violence against women and its causes, and remedy its consequences.

Although the Special Rapporteur had highlighted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and communities as a particular focus of her visit, the study tour was structured to enable her to meet a cross-section of organisations and individual women. The tour encompassed meetings with the Federal Attorney-General, federal, state and territory government representatives, service providers, business representatives, academics and community representatives, including representatives from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities from both urban and rural areas, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, women with disability, women of diverse sex, sexuality and/or gender, young women, and older women.

In the course of the study tour, 27 roundtables, meetings and site visits were held across four states and territories, including:

- Sydney, New South Wales

- Fitzroy Crossing, Western Australia

- Alice Springs, Northern Territory

- Melbourne, Victoria

- Canberra, Australian Capital Territory

See Appendix A for the schedule of the study tour.

During the study tour, the Special Rapporteur was accompanied by a member of the Commission and a documentor.*

A range of issues arose throughout the study tour for discussion with the Special Rapporteur. These included:

- the implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (National Plan);

- domestic violence and sexual assault, including programs for men to reduce violence against women; and

- the impact of culture, race and gender on the extent, nature and management of violence against women.

As the study tour was not an official mission, no formal report will be produced by the Special Rapporteur. However, the visit will inform the Special Rapporteur’s work and, in particular, her forthcoming thematic reports.

This report, prepared by the Commission, identifies the key issues and themes on violence against women in Australia that emerged during the roundtables, meetings and site visits in the course of the study tour. A summary of the key issues raised is provided below.

Key issues

Violence against women as a human rights issue

- The failure to articulate violence against women as a human rights issue was a common concern in discussions.

- The National Plan recognises the right to live safe and free from violence and this should also inform the implementation of the National Plan.

- Where governments fail to address the issue in human rights terms it can lead to an inappropriate and inadequate response by government and state agencies with long-term social and economic consequences.

- It was frequently noted that discrimination against women is a cause and consequence of violence against women.

* The Special Rapporteur was accompanied by Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Ms Elizabeth Broderick; Deputy Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Associate Professor Andrea Durbach or the Director, Sex Discrimination Team, Ms Alison Aggarwal. Ms Lucia Noyce was the documentor.

The risks of ‘mainstreaming’ and the need to ensure specificity and intersectionality in plans, programs and services addressing violence against women

- ‘Mainstreaming’ violence against women programs results in a formal rather than substantive equality approach to program design and content.

- Men’s programs can often divert essential resources from critical women’s services.

- Integrating the specific needs of women with disability, women from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander or migrant and refugee communities into plans, programs and services aimed at the prevention and redress of violence against women is essential to effective outcomes.

- The lack of recognition of the impact of intersectional discrimination based on sex, race, disability, and sex/gender identity on violence against women, often undermines the utility or effectiveness of plans and programs aimed at reducing violence.

- The absence of integration of the role and impact of cultural, political, social historical and inter-generational trauma in understanding and addressing violence against women leads to simplistic justifications of violence and one-size-fits-all formulations of programs that lack requisite cultural and psychological training components.

Effective program design and service delivery require comprehensive consultation, adequate funding, appropriate coordination and regular monitoring and evaluation

- The disconnection between government plans, programs and projects aimed at preventing, addressing and reducing violence against women and the needs of women ‘on the ground’ is a manifestation of:

- an inadequate meaningful and effective consultation with women, particularly in the implementation of the National Plan;

- a lack of dedicated, sustainable resources and funding models for both preventative and response based services (which recognise the long-term, protracted nature of the crisis rather than short-term, quick-fix approaches);

- a lack of service providers transferring skills and building capacity within communities who are well-positioned to deliver effective services; and

- a lack of regular monitoring and evaluation of programs, in particular the lack of independent monitoring and evaluation of the National Plan, and of service providers to inform programs; this is exacerbated by the lack of disaggregated data and analysis.

Although many state governments have developed impressive integrated (cross-departmental) models to address and prevent violence against women, there was a concern around the lack of coordinated implementation of the National Plan, within and across governments.

- In the absence of the Council of Australia Governments (COAG) first three-year implementation plan, the execution of the National Plan to date has been ad-hoc and implemented without adequate consultation.

- The need for governments across all jurisdictions to demonstrate their leadership to addressing violence against women and fully commit to the effective implementation of the National Plan was repeatedly noted.

- There is a need for central focal points within government to address violence against women and ensure cross-departmental or integrated development of programs. For example:

- the lack of adequate housing and homelessness arose as a constant issue, especially within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: dire over-crowding exposes children to violence and alcohol/substance abuse and early sexualisation due to lack of privacy; limited opportunities for learning and playing exist; refuges meet a limited short-term need, but are unable to effectively provide follow-up services;

- workplace/industrial relations and health departments need to work collaboratively on the long-term impact (physical and emotional) of domestic violence in workplaces; and

- the lack of gender-specific correctional facilities gives rise to women prisoners (often victims with a history of domestic violence) being held in maximum security prisons with male prisoners leading to an increased risk of abuse.

Impacts of violence against women on children

- Although the study tour had a specific focus on women experiencing violence, the immediate and long-term impact of violence on children – both as victims and observers – was a key issue of discussions. Educational initiatives (the development of healthy and respectful relationships) were seen as important, but the urgent need to address impact meant that crisis services were under considerable and increasing pressure and prevention strategies are, consequently, under-resourced.

Benefits of the study tour

The Special Rapporteur’s study tour to Australia and the related engagement with federal, state and territory governments, service providers, NGOs and individuals was well-received.

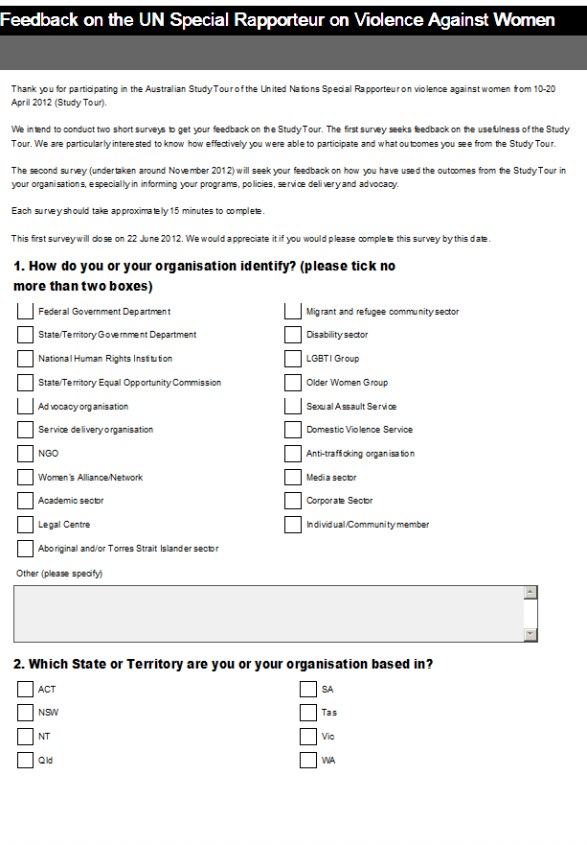

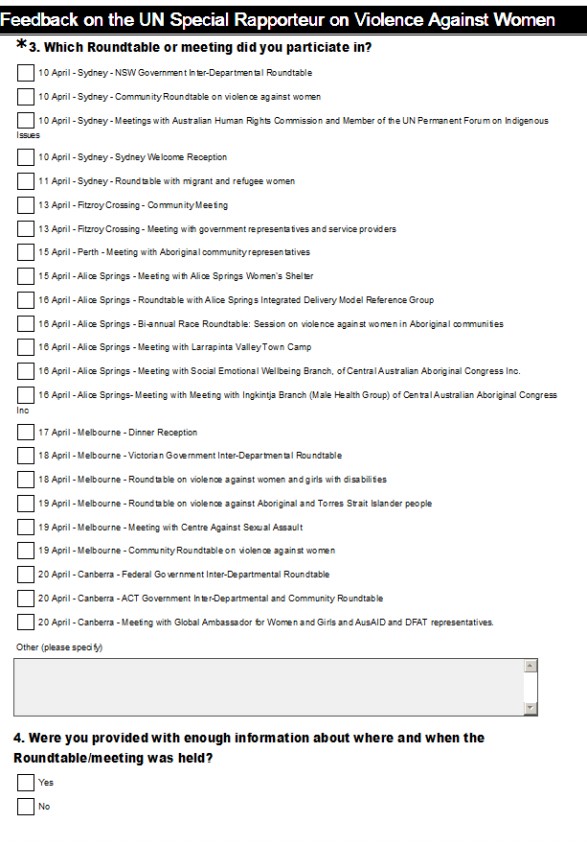

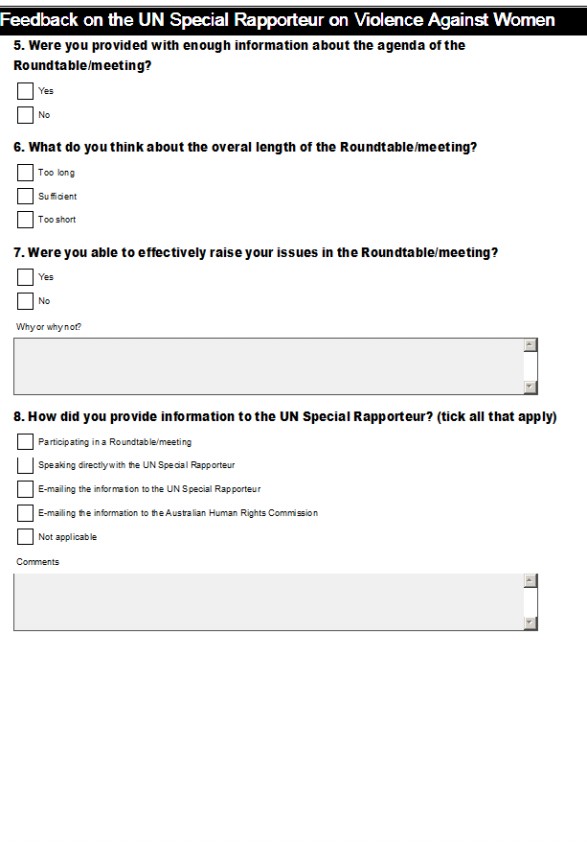

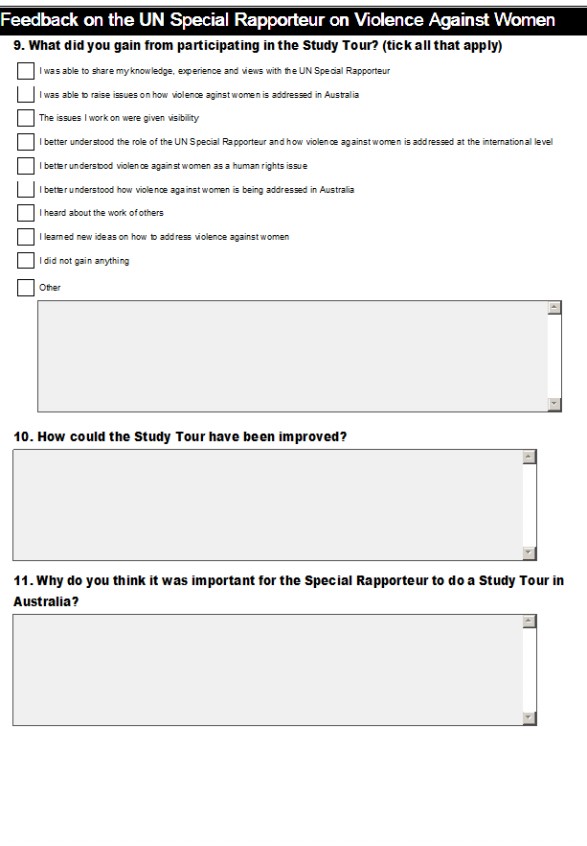

Recognising the value of monitoring and evaluating the impact of initiatives such as the study tour, at the conclusion of the study tour, the Commission conducted a survey among participants.

The feedback from the survey confirmed that the study tour provided an important opportunity for a range of stakeholders to meet and discuss the current status of violence against women in Australia, share information on the work and best practices for addressing violence against women in Australia and identify areas where further attention is needed. Respondents reflected a high level of satisfaction with the organisation of the study tour. Details of the survey results are provided in Appendix B.

Chapter 1: UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women2

1.1 Mandate

Rashida Manjoo was appointed UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences in 2009. As Special Rapporteur, she is required to:

- (a) seek and receive information on violence against women, its causes and consequences from governments, treaty bodies, specialised agencies, other special rapporteurs responsible for various human rights questions and intergovernmental and non-governmental organisations, including women's organisations, and to respond effectively to such information;

- (b) recommend measures, ways and means at the local, national, regional and international levels to eliminate all forms of violence against women and its causes, and to remedy its consequences;

- (c) work closely with all special procedures and other human rights mechanisms of the Human Rights Council and with the treaty bodies, taking into account the request of the Council that they regularly and systematically integrate the human rights of women and a gender perspective into their work, and cooperate closely with the Commission on the Status of Women in the discharge of its functions; and

- (d) continue to adopt a comprehensive and universal approach to the elimination of violence against women, its causes and consequences, including causes of violence against women relating to the civil, cultural, economic, political and social spheres.3

The Special Rapporteur addresses all forms of violence against women and girls in the family, the community, the state and the transnational context (e.g. violence against migrant and refugee women).

In accordance with her mandate, the Special Rapporteur undertakes fact-finding country missions and submits corresponding country reports to the UN Human Rights Council.4 In the past year, the Rapporteur has carried out country visits in Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Italy, Jordan and Somalia.

The Special Rapporteur also submits annual thematic reports to the Human Rights Council, which report on activities undertaken and themes analysed under the mandate.5 To date, Ms Manjoo has submitted three thematic reports concerning reparations for women subjected to violence (2010),6 multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination and violence (2011),7 and gender-related killings of women (2012).8

In addition, the Special Rapporteur may transmit urgent appeals and individual complaints to states regarding allegations of violence against women.9 Allegations may concern one or more individuals, or address a general prevailing situation condoning and/or perpetrating violence against women.10

The Rapporteur also interacts with UN bodies on the issue of violence.

1.2 Key issues

- During her study tour of Australia, the Special Rapporteur set the framework for discussion within the terms of her mandate and highlighted several key issues from her annual reports.

- These issues, many of which were considered at the study tour roundtables and meetings, included:

- identifying gender-based violence against women as both a cause and a consequence of discrimination against women and recognition of domestic and family violence as a ground of discrimination under national laws;

- identifying violence against women as a manifestation of patriarchy and historically unequal relations between women and men, which have led to domination over, and discrimination against, women by men;

- addressing violence against women from a human rights perspective rather than from a welfare perspective, or as an issue that affects specific groups only;

- applying the obligations of states to respect, protect and fulfil women’s human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the obligation to exercise due diligence to prevent, investigate, punish and remedy gender-based violence against women;

- debunking the myth that violence against women is a private issue that falls outside the scope of state responsibility;

- addressing the root causes of violence and the multiple and intersecting layers of discrimination;

- ensuring measures adopted to address violence apply a holistic approach and are realised in practice;

- highlighting the importance of prevention work in addressing violence against women, the absence of which results in increasing levels of deaths of women in the home and in the community;

- providing comprehensive redress measures which have a transformative potential and are not limited to compensation;

- addressing the multiple dimensions of discrimination and violence against women and reviewing and modifying a one-size-fits-all approach to service delivery; and

- establishing independent monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to measure the effectiveness of national laws and policies to address violence against women.

Chapter 2: Violence against women in Australia

2.1 Prevalence of violence against women

Violence against women is one of the most prevalent manifestations of human rights abuse in Australia.

- One in three women in Australia has experienced physical violence since reaching the age of 15.11 Of those women, 85% were assaulted by a current or former partner, family, friend or other known male.12 Three quarters of these physical assaults occurred in the woman’s home.13

- Almost every week in Australia one woman is killed by her current or former partner, often after a history of domestic violence. These intimate partner homicides account for one fifth of all homicides.14

- Almost one in five women in Australia has experienced sexual assault since reaching the age of 15.15

- In the 12 months prior to 2006 (when the last national data on violence against women was collected by the Australian Bureau of Statistics), younger women experienced violence at higher rates than older women. Twelve per cent of women aged between18 and 24 years had experienced at least one incident of violence, compared to 6.5% of women aged 35-44 years and 1.7% of women aged 55 years and over.16

- In a recent survey of rural women undertaken by the National Rural Women’s Coalition – one of six national women’s alliances in Australia – over 83% of respondents were concerned about health issues, including access to and the provision of health services, the cost and distance to services, and support for addressing domestic and family violence.17

- Limited data is available on the prevalence of violence against women and girls with disability in Australia.18 However, there is some evidence that suggests that women with disability face an increased risk of violence, exploitation and neglect, including in institutional contexts. Evidence also suggests that women with disability are less likely than others to receive appropriate assistance to deal with violence and prevent its recurrence.19

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are 45 times more likely than non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to be victims of domestic and family violence20 and 35 times more likely to be hospitalised as a result of family violence-related assaults than non-Indigenous women.21 The homicide rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are between

9 and 23 times higher at different times in the life cycle than they are for non-Indigenous women.22 - A 2008 national survey found that 22% of women and 5% of men aged between 18 and 64 years have experienced sexual harassment in the workplace in their lifetime, compared to 28% of women and 7% of men in 2003. It also found that approximately one in three women in Australia aged 18-64 years had experienced sexual harassment in their lifetime. The majority of this harassment occurred in the workplace (65%).23

- Research shows that domestic and family violence is the leading contributor to death, disability and illness in women aged 15 to 44 years. It is responsible for more of the disease burden in women than many well-known risk factors, such as smoking and obesity.24

- Recent research has also demonstrated the enduring mental health problems that affect survivors of domestic and family violence.25

- Violence against women and children will cost the Australian economy $15.6 billion per year by 2021-2022 unless effective action is taken to prevent this violence.26 The cost of productivity losses are expected to rise to $609 million per year by 2021-2022, unless effective action is taken to address domestic violence.27

2.2 Policy framework for addressing violence against women

The National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children,

2010-202228 is Australia’s primary policy on violence against women. Adopted in March 2011, the National Plan aims to: reduce violence against women and their children; improve how government works together to reduce such violence; increase support for women and children; and create innovative and targeted ways to bring about change. The federal government and all state and territory governments have committed to the National Plan and its implementation.

The National Plan identifies six national outcomes for all governments to deliver during the life of the National Plan:

- (1) communities are safe and free from violence;

- (2) relationships are respectful;

- (3) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are strengthened;

- (4) services meet the needs of women and children experiencing violence;

- (5) justice responses are effective; and

- (6) perpetrators stop their violence and are held to account.

It also commits to the creation of a National Centre of Excellence to ‘bring together existing research, as well as undertake new research under an agreed national research agenda’.

A National Plan Implementation Panel, consisting of government and non-government representatives, was established in April 2012 to advise on the implementation of the National Plan.

To date there has been implementation of some parts of the National Plan. Some elements of this include:

- the establishment of the 1800 RESPECT: National Sexual Assault, Family

& Domestic Violence Counselling Line for victims and survivors, which operates 24 hours a day; - implementation of a Respectful Relationships education project that fosters whole-of-school approaches to respectful relationships and involves staff, parents, students and community agencies;

- implementation of The Line, a social marketing campaign aimed at educating and encouraging young people to develop healthy, respectful relationships;

- allocation of $3.75 million over four years for community organisations to deliver prevention programs that increase community awareness and change attitudes and behaviours that foster violence against women;

- allocation of $750,000 to sport groups to undertake prevention programs; and

- commencement of the ABS 2013 Personal Safety Survey.

To date, the COAG first three-year implementation plan has not been finalised and a National Centre of Excellence is yet to be established.

Chapter 3: Government roundtables

The study tour followed a similar itinerary in each state: initial government roundtables, followed by general and specific community roundtables. This section focuses on the key issues, policies and programs discussed during the government roundtables. Many of these issues were echoed at the community roundtables, discussed in subsequent sections.

Five government inter-departmental roundtables were held during the study tour.

- On April 10, the Australian Human Rights Commission and the New South Wales Office for Women’s Policy co-hosted the NSW Government roundtable in Sydney.

- On April 16, the Commission and the Northern Territory Department of Justice

co-hosted the NT Government roundtable in Alice Springs. - On April 18, the Commission and the Victorian Office for Women’s Policy

co-hosted the Victorian Government roundtable in Melbourne. - On April 20, the Commission and the Safety Taskforce Branch of FaHCSIA

co-hosted the federal government roundtable in Canberra. - On April 20, the Commission and the ACT Office for Women co-hosted the ACT Government and community roundtable in Canberra.

- On 20 April, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Penny Williams, Global Ambassador for Women and Girls, hosted a roundtable with AusAID and the Commission in Canberra to discuss programs to combat violence against women in the Pacific.

Each roundtable was attended by representatives of the relevant federal, state and territory governments. Much of the information shared about measures adopted by the respective governments to eliminate violence against women was descriptive rather than analytical, and this led to many discussions on the adequacy and effectiveness of those measures.

Key challenges

The Special Rapporteur identified the importance of federal, state and territory governments articulating and addressing violence against women as a human rights issue as key to meeting their stated objective of reducing violence against women.

Challenges identified during roundtable discussions included:

- structural gender inequalities;

- the failure to acknowledge the culture of violence against women in Australia;

- the tendency to blame women for their experiences of violence;

- inadequate refuges and housing;

- insufficient resources and capacity to address violence;

- inadequate collaboration, integration and uniformity across government departments;

- lack of comprehensive collation and disaggregation of data; and

- a lack of understanding as to whether the increase in reporting of domestic violence suggests greater prevalence or greater awareness of the issue.

3.1 Federal government roundtable

Below is a summary of key issues that were raised by representatives from various federal government departments (see Appendix A for a list of participants).

Data collection

- The Australian Bureau of Statistics collects a range of data about domestic and family violence in its National Crime Victimisation Survey and Personal Safety Survey. The next Personal Safety Survey, which specifically collects data on violence – including emotional abuse – against women (and men) by current and/or previous partners, will be available around mid-2013.

- There is limited information collected in the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey about violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, due to the cultural and safety issues in collating such sensitive data.

Domestic violence as a workplace issue

- The impact of domestic violence on working women has been recognised in workplaces agreements, for example in clauses on leave and flexible working arrangements. Much of this work has been developed by the Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse’s Workplace Rights and Entitlement Project, which is funded by the federal government. The Clearinghouse has developed a related training program for unions and employers.

- The issue of domestic violence and discrimination in the workplace was raised and is addressed in more detail in Section 5 below on the general community roundtables.

Violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women

- Overcrowded housing remains a priority problem in addressing domestic and family violence in Aboriginal communities.

- Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory is an Australian Government commitment of $3.4 billion over ten years to make communities safer and families and children healthier. The investment will include the introduction of an additional 15 new Communities for Children program sites and 23 intensive family support services for children and families at risk. The federal government will continue to support funding for remote policing, women’s safe houses, Remote Aboriginal Family and Community Workers, alcohol restrictions, community night patrols, National Indigenous Violence and Child Abuse Taskforce, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Legal Services, Women’s Legal Services, income management scheme and prohibitions on considering customary law in bail and sentencing decisions.

- The Men’s Safe Places were established under the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) as places for men to detoxify. However, a number of men in those communities viewed them as places of shame. The evaluation of the NTER and the consultations leading to the development of the Stronger Futures for the Northern Territory package indicated a preference for a broad based men’s health and wellbeing service. Under Stronger Futures, in the NT Child, Youth, Family and Community Wellbeing Package, Men’s Safe Places will be integrated into the new Communities for Children program, and a new program providing men with services focused on parenting, leadership, employment, education and health will be implemented.

Support for refugee women

- Australia receives approximately 13,750 refugees and asylum seekers each year,29 of which approximately 6000 places are for women refugees.

- Approximately 12% of the refugee places are for ‘women at risk’ visa holders.30 The ‘women at risk’ visa, is available to single women and their children, who are vulnerable to victimisation, harassment or serious abuse because of their gender. The visa affords priority access to counselling and other services.

Family law

- In November 2011, the Commonwealth Parliament passed the Family Law Legislation Amendment (Family Violence and Other Measures) Act 2011 to respond more effectively to family violence and child abuse, and to prioritise the safety of children in family law proceedings.31

Health

- In 2010, the Australian Government launched the National Women’s Health Policy, which aims to improve women’s health and wellbeing. The policy recognises that women’s security, including from violence, is a determinant of health.32 It also recognises that violence against women has a significant disease burden and negative consequences for women’s health. The federal government has identified the need for appropriate training for general practitioners, nurses, mental health, drug and alcohol services and other frontline health workers to identify and respond effectively to women experiencing violence.33

International Development Assistance Program

- The International Development Assistance Program is focusing efforts to combat violence against women in the Pacific on improving hospitals and shelters, skilling service providers, improving access to justice for women (e.g. gender equality training for police and village magistrates) and supporting female law reform advocates.

- The Australian Government has contributed to a $9.6 million fund to combat violence against women in the Asia Pacific and Middle East region and is funding violence against women prevalence studies across the Pacific.

- Combating violence against women is a key priority of the Global Ambassador for Women and Girls, Penny Williams, whose focus is the Pacific.

3.2 State and territory government roundtables

Below is a summary of key issues that were raised by representatives from various state and territory government departments (see Appendix A for a list of participants).

Prevalence and reporting of violence across state and territories

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are more than 2.5 times as likely as non-Indigenous women to have been a victim of physical or threatened violence.34 Domestic and family violence rates are high in the NT, especially in Alice Springs. Fifty six per cent of assaults in Alice Springs in the year ending March 2011 were related to domestic and family violence. Two thirds of all assaults are alcohol related. Approximately 75% of children seen by the NT Department of Children and Families are impacted by domestic and family violence in some way.

- In the two years prior to March 2012, 38% of recorded violent crimes in NSW were related to domestic and family violence or sexual assault.35 A 2010-11 survey estimates that the reporting rate for physical assault in NSW is 55% and 39% for sexual assault.36

- In 2010-2011, 40,892 incidents of domestic and family violence were reported to Victoria Police. Victoria Police also recorded 1826 rape offences and 5735 sex (non-rape) offences in 2010-11. Across both areas of crime, approximately 85% of victims are females and 15% are males, including children.

- In Victoria, growing public awareness that family violence is unacceptable and often unlawful, together with the enhanced police response to the investigation of family violence matters has resulted in more people reporting family violence and an increase in family violence intervention orders being sought at the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria (MCV). There has been a 294% increase in the number of family violence related applications to the Magistrates’ Court by Victoria Police since 2003-04, with increasingly limited capacity to respond.

- One in three women have experienced violence since the age of 15 and report domestic and family violence, and 12% of women and 4.5% of men report being sexually abused before the age of 15.37

Access to housing

- Domestic and family violence is the largest cause of homelessness in Australia.

- There is a lack of available refuges and housing in Australia for victims of domestic and family violence. In NSW, for example, up to 40,000 women are on the housing waiting list at any given time and many stay in abusive relationships to avoid homelessness.

- There is a triage system for public housing in the Australian Capital Territory. ‘Women and children escaping domestic violence’ is a priority category and are allocated 8% of the ACT housing stock.

- The NSW Department of Housing offers housing and rental assistance to victims/survivors of domestic violence, including through the Start Safely Program and the Staying Home Leaving Violence Program. A key goal of such assistance is to avoid homelessness. The Department has a memorandum of understanding with NSW Police to identify women at risk of homelessness due to violence and assist them in accessing housing or upgrading security at their residence.

- Domestic and family violence responses in Victoria include assistance with home stay and access to private rental properties which often is a catalyst that enables women to re-enter the work force. The Victorian Equal Opportunity Act 2010 requires consideration to be given to how homelessness and housing responses address domestic/family violence.

Access to justice

- In the ACT:

- the ACT Prevention of Violence against Women and Children Strategy is a local manifestation of the National Plan objectives. The Strategy aims to drive service and legal reform to better service victims and increase accountability. The Strategy also hopes to increase the focus on violence against women with disability and mental illness;

- the ACT Human Rights Act 2004 protects civil and political rights, authorises the ACT Human Rights Commission to intervene in cases and the Commissioner to request audits of institutions and detention facilities. Addressing violence against women is a key focus of the ACT Commission;

- magistrates have adopted the ACT Family Violence Prevention Plan which, among other things, affords victims greater privacy and security when giving testimony;

- there is a low uptake of legal and justice services to seek redress for assault and sexual harassment and tribunals often provide meagre financial redress;

- the Victims of Crime Commission has a domestic violence project coordinator who provides advice to the ACT Government and services to Victims Support ACT, promoting a pro-charge and pro-arrest approach; and

- the police play a central role in addressing domestic and family violence and sexual assault, and are supportive of prevention programs; police relationships with culturally and linguistically diverse communities can still be problematic, due to the fear and lack of trust of police within the communities.

- In NSW:

- over 32,097 Apprehended Violence Orders (AVOs) were issued in 2011, comprised of 24,903 Domestic AVOs and 7,194 Personal AVOs;38

- the majority of perpetrators of domestic violence and sexual assault are men, but there has been an increase in female and young perpetrators;

- there is a high level of recidivism;

- there are 117 Domestic Violence Liaison Officers, who act as a conduit between police and victims and provide support to victims and officers;

- the Department of Health provides 55 Sexual Assault Services;

- programs to assist victims include: Domestic Violence Court Model, which has led to significant improvements in victim outcomes; Women’s Domestic Violence Court Advocacy Program, which trains legal aid staff on domestic violence; Domestic Abuse Program, which provides workshops for male perpetrators and reduced recidivism by 22%; and Sexual Assault Communication Privilege Unit, which provides four years of funding to assist sexual assault victims; and

- the NSW Government designates 44% of trauma counselling services for victims/survivors of domestic and family violence; the NSW Victims Compensation Scheme distributes $70 million annually, with 60% of recipients being female.

- In Victoria:

- the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) recognises domestic and family violence as a human rights violation;

- the civil protection scheme prioritises the needs of victims to ensure court processes do not become another site of abuse;

- there is a positive duty to prevent violence and discrimination, and employers and other actors are required to address sexual harassment;

- there is a specialist family violence court division in several courts and the Coroner’s Court investigates domestic and family violence-related deaths;

- there is a common database for reports of domestic and family violence from police, courts, legal services, hospitals, refuges and others, which has assisted in identifying demand for services;

- the Family Violence Risk Assessment and Risk Management Framework (CRAF) is a key component of the integrated family violence system; it is underpinned by a state-wide training program for professionals and practitioners working in a wide range of fields to instigate a shared understanding of family violence and a common approach to the assessment and management of risk;

- the Sexual Assault Reform Strategy attempts to increase sexual assault reporting, including by improving victim confidence in the justice system, principally by strengthening the way that the justice system responds to sexual assault victims; in most years since the Strategy commenced there has been an increased rate of reporting;

- key changes in the system as a result of the Sexual Assault Reform Strategy include the use of remote witness facilities for sexual assault victims and the introduction of the Child Witness Service;

- Victoria Police adopted a Human Rights Framework in 2007; police members have access to up to 60 hours of human rights training (depending on their workplace) and undertake regular human rights compliance assessment;

- Victoria Police guides its responses to violence in line with the Victoria Police Strategy to Reduce Violence against Women and Children 2009-2014 and it’s Code of Practice for the Investigation of Family Violence and Code of Practice for the Investigation of Sexual Assault. For example, since 2003-04 when the Code of Practice for the Investigation of Family Violence was implemented, there has been:

- 48% increase in reports of family violence incidents to police;

- 289% increase in charges laid by police arising from family incidents;

- 294% increase in applications for intervention orders by police;

- police are the applicant in approximately 56% of family violence applications to the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria;

- police resources for addressing violence against women include ten family violence teams and 27 sexual offences and child abuse units, and there are plans to expand those resources. Victoria police also have 13 Family Violence Advisors across the state and approximately 180 Family Violence Liaison Officers;

- Victoria has also rolled out three Multidisciplinary Centres that respond to sexual assault and child abuse in Mildura, Frankston and Geelong. They are a ‘one stop shop’ for victims and co-locate police, child protection and the centres against sexual assault agencies to improve responses to victims of these crimes.

- In the NT:

- the Alice Springs Transformation Plan provides $3.2 million for the Alice Springs Integrated Response, which aims to increase safety for women and children, increase perpetrator accountability and facilitate behavioural change.

Access to support services

- It was acknowledged that support services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in the ACT are inadequate to meet the needs of victims/survivors of violence (and their children, in many instances) and require additional resources, expansion and modification.

- The ACT Prevention of Violence against Women and Children Strategy will inform the Wrap-Around Program on sexual assault.

- In Victoria, the government provides a range of support services for victims of family violence and/or sexual assault, as well as programs that aim to change the behaviour of those who perpetrate violence. These include outreach, case management, counselling, advocacy and accommodation services for victims; treatment programs for young people displaying sexually abusive behaviour; and case management and behaviour change programs for men who perpetrate violence. The voluntary service system is experiencing a surge in demand. In Victoria, where police respond to an incident of family violence or sexual assault, a referral is made to relevant support services as part of the integrated system that has been developed. This is guided by the Codes’ of Practice for Family Violence and Sexual Assault.

Chapter 4: General community roundtables

Government funding needs to be made available for both primary prevention programs and response services for crisis needs.

A series of general community roundtables were held to identify overarching issues concerning violence against women in Australia.

The first roundtable, held at Redfern Community Centre in Sydney on 10 April 2012, was co-hosted by the Commission, Women’s Legal Services NSW, Kingsford Legal Centre and NSW Rape Crisis Centre.

The second roundtable, held at VicHealth in Melbourne on 19 April 2012, was

co-hosted by the Commission, the Australian Women Against Violence Alliance (AWAVA), VicHealth and Domestic Violence Victoria (DV Vic).

The third general roundtable held in Canberra on 20 April 2012 was co-hosted by the Commission and the ACT Office for Women.

The roundtables were attended by representatives from Aboriginal organisations, women’s organisations, older women’s groups, women with disability groups, LGBTI organisations, migrant and refugee women’s services, domestic violence services, sexual assault services, anti-trafficking organisations, legal services, health groups, members of the community and academics (see Appendix A for a list of participants).

In addition to the general community roundtables, there were specialist roundtables held for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, women from migrant and refugee communities, and women with disability. While issues relating to these specialist roundtables were also raised in the general community roundtables, these issues are reported in the section on the relevant specialist roundtables and are not included in this section.

Key issues identified by general community roundtable participants concerning violence against women are outlined below. Examples of programs for preventing and addressing violence against women, which were raised in the discussions, are profiled in Appendix C.

National Plan

- The adequacy of the National Plan and the steps taken by government (both at the federal and state/territory levels) to implement the National Plan emerged as key issues.

- Continued bipartisan commitment by all Australian Governments to the National Plan and its implementation is critical.

- Full and proper resourcing and funding for the National Plan is also essential to its successful implementation.

- Independent monitoring and evaluation and the provision of appropriate resources for the National Plan are essential to its long-term utility. The absence of monitoring and evaluation mechanisms has meant that there is limited benchmark data for assessing the effectiveness of the National Plan’s implementation. This has resulted in the inability to track whether the National Plan adequately meets the actual needs of victims/survivors of violence. It has also resulted in the inability to assess whether or not the funds being expended under the National Plan are sufficient and being appropriately utilised.

- The implementation of the National Plan needs to be undertaken in conjunction with both government and community stakeholders to ensure community engagement and an intersectional approach to violence against women.

- The National Plan needs to include authentic prevention programs that are aimed at behavioural and cultural change, not just information provision. Existing services are over-extended and under-resourced, leaving them with limited capacity to undertake primary prevention work.

- UN Women’s proposal for universal access to critical services to address domestic and family violence could establish an important minimum core standard for service provision under the National Plan, ensuring access to support across all parts of Australia and among all marginalised groups.39

- The full implementation of the National Plan has, however, been impeded by:

- the COAG first three-year implementation plan not being developed or agreed to;

- the federal government not releasing the report on the consultation (conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers) on possible models for a National Centre of Excellence nor releasing a proposal for the establishment of the Centre;

- the limited consultation with non-government stakeholders and affected communities on the implementation of the National Plan, which has resulted in inadequate attention to the development of specific programs for marginalised groups of women.40

Domestic and family violence

- Domestic and family violence is the leading contributor of death for women aged between 14 and 44 in the state of Victoria. The economic impact on workplaces is expected to rise to $609 million per year by 2021-2022.41

- Homelessness, one of the main consequences of domestic violence, remains a critical problem with inadequate refuge and public housing options available.

- Insufficient resources are available to address domestic and family violence, especially in rural areas.

- Generally, there is an absence of a comprehensive, integrated response to domestic and family violence.

- There is a need for a national, uniform standard for evaluating solutions to domestic violence.

- There is a growing awareness of domestic violence as a workplace issue and the need to recognise domestic violence as a ground of discrimination in anti-discrimination legislation was widely supported.

Sexual assault

- Forty-one per cent of sexual assaults in Australia are experienced by children between the ages of 0 and

14 years.42 This age group is less likely to report sexual assault. - Sexual assault of children is difficult to prosecute because the victim/witness is a child and the perpetrator is often a family member or friend.

- Rates of conviction for sexual assault are low. For example, a New South Wales study found only 10% of reported perpetrators of sexual assault against children were convicted.43

- The ACT experience suggests that specialist processes within the court system for addressing sex offences may help to secure conviction rates for sexual assault and help women to better understand the law and their rights. This system should integrate civil, criminal and family law proceedings, be well-resourced and receive support from high-level political leaders.

- Many children who have alleged violence or sexual assault by a family member are removed from their families if, for example, a parent initiates family law proceedings, often with grave consequences for the child.

- There is a need for a holistic approach to sexual assault that encompasses all aspects of the justice process and service provision.

Older women

- Older women face a heightened risk of violence (perpetrated by family members and in aged-care facilities) and specific obstacles in escaping violence and accessing treatment. Reasons for this include their physical vulnerability, increased dependency and limited economic power.

- The National Plan does not adequately address older women’s needs and interests and their specific vulnerability to violence.

- There is no specific research on the experiences of domestic violence among older women of diverse sex, sexuality and/or gender in Australia. These groups are particularly vulnerable and invisible, and have specific support needs.

Women of diverse sex, sexuality and/or gender

- One in three women of diverse sex, sexuality and/or gender experience domestic and family violence, a similar rate to women in the wider population. Further research is required to ascertain the prevalence and nature of violence experienced within this group.

- Anecdotally, it is known that these populations are significantly less likely to report, seek support or identify experiences of domestic violence or other types of violence and abuse.44

- Women of diverse sex, sexuality and/or gender have specific needs in relation to domestic/family violence support. Yet, there are significant gaps in service provision for these women who are victims/survivors of violence, leaving many women without support:

- there is a lack of culturally appropriate service providers. In NSW, it was reported that women of diverse sex, sexuality and/or gender have experienced homophobia and transphobia from mainstream service providers;

- access to services can be restricted when both the victim and perpetrator are trying to access the same service and the services are consequently ‘conflicted out’;

- particular challenges are faced in accessing services in rural areas because services are even more limited in rural areas and some women may not be out to their local community; and

- there is no 24/7 specialist domestic/family violence phone support service operating anywhere in Australia for women of diverse sex, sexuality and/or gender.

- The gendered model of domestic and family violence translates to an invisibility of victims/survivors and perpetrators of diverse sex, sexuality and/or gender. At federal, state and territory levels, domestic and family violence among women of diverse sex, sexuality and/or gender needs to be explicitly recognised, included and prioritised as a vulnerable non-homogenous group with varying needs.

Women in prisons

- Women are overrepresented in Australian prisons, especially for minor offences. One reason for this is that many women cannot satisfy bail conditions, for example due to a lack of available housing.

- There is a high incidence of women in prison who have been victims/survivors of domestic violence and/or sexual assault.

- It was reported that in Queensland there have been instances of police violence against women in prisons, including rape.

- Many prisons require women to undergo highly invasive and often traumatic strip searches that are not proportional to the aim of preventing contraband entering prison facilities.

- It was reported that women prisoners in Queensland, especially Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners, have had their children removed from their custody, despite policies allowing for women in prison to retain custody of their children.

- Access to counselling services for women prisoners requires improvement and women require specific counselling services in prison which address the consequences of violence. Different views were expressed regarding whether such services should be provided during or following a term of imprisonment.

- It was reported that Trans women in male prisons experience disproportionally high rates of violence.

Men’s programs

- The positive work undertaken by men’s organisations to address violence against women was acknowledged.

- However, it was noted that men’s programs need to be grounded in efforts to challenge patriarchal structures and gender inequality.

- A point raised at a number of roundtables was that, while funding for appropriate men’s programs is required and men should be supported to organise themselves, resources should not be diverted away from already under-resourced women’s services or at the expense of support for women’s organisations.

- It is not appropriate for men of diverse sex, sexuality and/or gender to be required to participate in mainstream men’s groups; culturally appropriate men’s programs needs to be available for this group.

Community attitudes

- Gender inequality was acknowledged as the root cause of violence against women. A failure by governments and service providers to recognise this as a cause of violence against women when developing plans, programs and services undermines their efficacy and the reduction – and eventual elimination – of violence against women.

- Violence against women continues to be regarded as a private matter, often with the consequence that it is ‘normalised’ or tolerated.

- Despite the high prevalence rates of violence against women in Australia, there is resistance to acknowledging that Australia has a culture of violence against women.

- In order to shift community attitudes, prevention programs that focus on behavioural and cultural change are required. In addition, there is a need for more visible leadership and political commitment to addressing violence against women as a national priority.

Access to services45

- As was noted in the government roundtables, there is a high level of unmet demand in refuges and shelters, with one in two women who are victims/survivors of violence being turned away.

- There are limited services available, particularly in rural areas, to assist victims/survivors of domestic and family violence.

- Government funds are not being directed to grassroots services, especially culturally specific programs.

- Existing services are overstretched and, therefore, unable to undertake necessary primary prevention work. Government funding needs to be made available for both primary prevention programs and response services for crisis needs.

Access to justice

- Police commonly issue dual AVOs against both parties in a violent relationship. There has been a spike in women arrested for breaching AVOs, often due to a lack of awareness of how they operate. There are limited legal services available to assist women who have breached an AVO and, consequently, many women plead guilty and serve inappropriate jail sentences.

- Australian states and territories administer victims’ compensation schemes, which are available to victims of domestic and family violence and sexual assault. These schemes could be strengthened to better meet the needs of victims. Particularly by removing the distinction with respect to ‘related acts’ which treats acts of violence committed by the same offender as a single eligible incident for the purposes of compensation, and by ensuring that schemes include access to free, non-compulsory counselling, to assist victims and survivors to deal with the lasting impacts of the violence they have experienced.

- Different views were expressed about the utility of a specialist sex offences court system. It was, however, felt that such an initiative would grant women greater access to the criminal legal system, enable them to better understand their rights and ensure perpetrators are held to account.

- In Victoria, the increase in reporting of family violence incidences has placed significant pressure on an under-resourced court system. This results in long waiting times at court and delays in hearing cases. Community legal centres that provide duty lawyer services to assist women in court are similarly under-resourced.

- Many women still find it difficult to access information and support regarding the legal process. Women’s access to justice can be obstructed because:

- many women get lost in the process, as they move from one service provider to another, and can find it difficult to navigate the system;

- the overly legalistic and complex nature of the legal system can be disempowering for victims/survivors; and

- legal representation is often inaccessible due to cost (ie private lawyers’ fees can be prohibitively expensive) or due to the failure to meet legal aid criteria (ie legal aid guidelines preclude many women who are on a low incomes).

- While an increase in reporting of domestic and family violence incidents had been noted, there is not a corresponding increase in convictions of perpetrators.

- Addressing offending behaviour is integral to preventing further violence. Yet it is one of the weakest elements of the family violence system. As such, appropriate resources must be committed to addressing offending behaviour.

Chapter 5: Violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women roundtables46

On 19 April 2012, the Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention and Legal Services Victoria hosted a roundtable in Melbourne on violence against women in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. The roundtable was attended by approximately 15 people, including representatives from service providers and community organisations.

Key issues identified by roundtable participants as well as by participants in other general community roundtables concerning gender-based violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and issues identified in meetings held in Fitzroy Crossing are outlined below.

Prevalence and context of violence

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women experience higher levels of violence than non-Indigenous women in Australia. They are 45 times more likely than non-Indigenous women to be victims of domestic violence. However, logistical, sociological and cultural factors may hinder reporting and, therefore, these figures may underestimate the actual prevalence rate of violence. The distrust of police and the justice system also contributes to reduced reporting, prosecution and conviction of perpetrators.

- The context of violence is complex and the contributing factors are varied and interrelated. These include:

- a history of colonisation and dispossession, which has led to structural inequality, as well as high rates of poverty and unemployment;

For example, 93% of the Fitzroy Crossing population is Aboriginal. There are four language groups living in the region. Some of the older women of the community were alive when the community had first contact with non-Indigenous people. Many were brought to the area by their parents, to keep them safe from the massacres that were occurring. The history of colonisation and the threat to the culture and community means many women are reluctant go to the authorities to address their issues.

- the intersection of race and gender and the racialised and discriminatory nature of violence against women;

- the failure of governments to understand and address the specific needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples effectively;

There are very few culturally appropriate legal services accessible to Aboriginal women who are victims of violence.

- alcohol abuse, which is often portrayed as the primary contributor of violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women; however, little attention is paid to the underlying sociological reasons for alcohol abuse;

- limited housing and overcrowding, often resulting in the early sexualisation of children, children witnessing domestic and family violence, and being vulnerable to violence themselves; and

- the normalisation of violence against women within communities.

- Concerns were expressed about the need to address ‘culture’ being used as an explanation of, or justification for, violence against women in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. This concern is compounded by the perception of violence against women as a matter confined to the private sphere and that exposure of the violence may result in fragmenting both the family and community involved.

Access to justice

- A number of factors emerged that called for enhanced protection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women across the justice system:

- there are very few culturally appropriate legal services accessible to Aboriginal women who are victims of violence. Where the perpetrator is represented by the local Aboriginal Legal Service, this can result in no service being available to the victim;

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women incarcerated as a consequence of actions they have taken to defend themselves against an abusive partner often face obstacles in accessing culturally appropriate legal defence services;

- The Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention and Legal Services are part of a national program funded by the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department. They largely service Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children living in rural and remote locations, who are victims of domestic and family violence and sexual assault. Funding guidelines restrict service provision in urban areas in response to a government policy that determined rural and remote areas as those with the greatest need. However, this policy prevents Aboriginal women and children in urban areas from accessing culturally safe and sensitive legal services;

- there is a need for increased legal services and community legal education programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities living in urban areas. In addition, government funding for strategic policy development and law reform is essential in the area of women’s law and justice;

- women are reluctant to contact police in relation to domestic violence incidents for a number of reasons (e.g. mistrust of authorities, fear partners will be incarcerated, fear of incarceration if they have outstanding fines or warrants). It was noted that police in Redfern, Sydney, have agreed to address domestic violence issues prior to addressing other issues, such as fines or warrants;

- for victims/survivors of violence to access the justice system, their trust and confidence in the system can be undermined if their harm is exacerbated in any way or their concerns are not effectively addressed or resolved in a culturally sensitive and appropriate manner. Units in the Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention and Legal Services undertake considerable work within communities to build trust and confidence in potential users of the justice system. For example, FVPLS Victoria runs a Sister’s Day Out’ program, which is a wellbeing and legal workshop that has reached over 5000 Aboriginal women and girls in Victoria;47

- while coronial inquests into homicides resulting from a history of domestic and family violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are not common, it was noted that inquests provide an important avenue for exposing the failure of state agencies to act pre-emptively to prevent homicides (e.g. failure to respond by police, provide safe accommodation and shelter, and protect children). The Western Australian coronial inquest in 2012 into the death of a woman called Andrea is an example in this regard; and

- the issue of institutional violence emerged in relation to the incarceration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Many of these women are held in maximum security facilities, even if convicted of minor offences, and in close proximity to male perpetrators of sexual violence.

Access to services

- Women’s shelters or safe houses are an important initial stop gap for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who are victims/survivors of domestic and family violence. However, unless the underlying causes of domestic and family violence are more broadly addressed and ongoing funding is made available for these services, they can only be an interim measure and women will be captive to a ‘revolving door syndrome’.

- Services are generally provided on a piece-meal basis and are not cohesively focused on women and their children. There is a need to provide holistic, wrap-around services for women escaping domestic and family violence, including counselling, health and legal services.

- Young women and older women come to the Marninwarntikura Women’s Resource Centre shelter at Fitzroy Crossing. Most women stay in the shelter for two to three days until it is safe to return to their homes. During their stay, the workers provide counselling to both the women and their children, including access to a drug and alcohol counsellor. The workers note that there is a need for more counselling services for children and young people. Since the introduction of the alcohol restrictions in Fitzroy Crossing, the intensity of the damage in violent situations has reduced; there are fewer broken bones etc. Women are also now coming to the shelter in advance of any incidents occurring – if they see the signs that a violent incident is imminent, they come to the shelter first. AVOs are not used often in Fitzroy, as it is difficult in such a small community to maintain the required distance and separation, and this can cause problems for breaches of AVOs.

- A common concern was that services for victims/survivors of domestic and family violence have been ‘mainstreamed’ and are thus viewed as ‘culturally unsafe’ or inappropriate by many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. It was evident that effective services require the transfer of skills to, and the provision of services by, trained Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff, optimally women. In addition, more Aboriginal identified positions in mainstream services to assist with language and other issues are required.

- Some of the barriers that prevent Aboriginal women and children from accessing mainstream services include:

- racism and discrimination;

- fear of removal of children; and

- lack of cultural awareness and sensitivity among mainstream organisation staff.

- It was observed that genuine cultural change in the community is only achievable if programs are tailored to the circumstances of the specific community, and monitored and evaluated by the community these services are intended to benefit.

- Resources allocated for domestic and family violence services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women must be commensurate with demand for those services.

- Funding agreements must ensure that proper evaluation of services is undertaken and that results inform the provision of services.

- Services should not simply be limited to remedial measures, but must include a focus on education and prevention. There are a number of important models being developed that seek to address how to negotiate intimate relationships, cultivate respect and dignity in relationships, and raise awareness that domestic and family violence is a breach of human rights.

- In 2008, the Aboriginal community and the Victorian Government jointly developed a strategy to reduce Indigenous family violence. The 10 Year Plan (2008-2018) is a community-led partnership with the state government and is the first of its kind on Indigenous family violence in Australia. The 10 Year Plan focuses on education, prevention and early intervention in local Aboriginal communities to reduce incidents of Indigenous family violence across Victoria.

Engaging men

- It was acknowledged that successful domestic and family violence programs need to engage men, both as perpetrators and potential leaders in preventing and reducing violence against women.

- There is a need to ensure the rehabilitation of offenders in order to prevent the cycle of domestic and family violence.

- The NT Intervention has had a specific impact on men. It has stigmatised men as potential perpetrators, making them reluctant to engage in discussions about domestic and family violence. In addition, as noted above, men’s safe houses have been rejected as ‘places of shame’ and the federal government is reconsidering the program.

- There is a need for the male community leaders to play a public role in addressing domestic and family violence, work with male perpetrators and lead by example. In addition, these leaders must be seen to actively support women’s programs on domestic and family violence.

- Increasingly community workshops are providing safe places for men to talk about domestic and family violence and gradually violence awareness is growing among Aboriginal men.

Child protection

- In NSW, roundtable participants advised that domestic and family violence rates had decreased as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women feared that reporting incidence of such violence would lead to their children being removed from their custody.

- The increasing removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children into foster care and other child protection arrangements requires critical evaluation to ensure children are not caught up in a cycle of domestic and family violence, removal and institutional violence.

Leadership

- Governments must ensure that effective consultation and engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities occurs in the development of policies, programs or services aimed at reducing domestic and family violence in those communities. This can promote greater capacity within the Aboriginal community to take responsibility for and lead prevention strategies and service delivery. A view was expressed that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women could play an important role in implementing and managing research and programs on domestic and family violence. It was also noted that much could be gained from initiating dialogue between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal women on addressing domestic and family violence.

- In Victoria, the Indigenous Family Violence Partnership Forum, comprising senior representation from the whole of government, Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs), and ten Indigenous Family Violence Regional Actions Groups (IFVRAGs) from across Victoria provides advice and leadership on driving reform in the area of Indigenous family violence.

- In Fitzroy Crossing, women noted their time and resources are focused on simply surviving, leaving little time to engage in formal leadership roles. The annual Women’s Bush Camp is one opportunity for women to come together and talk about the issues that are important to them.

Chapter 6: Violence against migrant and refugee women roundtables48

On 11 April 2012, the Australian Human Rights Commission hosted a roundtable on violence against migrant and refugee women at the Bankstown Arts Centre in Sydney. The roundtable was attended by approximately 16 representatives of migrant and refugee women groups from Canberra, Melbourne and Sydney. Settlement Services International facilitated the roundtable.

Key issues identified by roundtable participants, and by participants in other general community roundtables, concerning gender-based violence against migrant and refugee women are outlined below.

- Migrant and refugee women may be unaware that the violence they are experiencing is unlawful in Australia and/or is a violation of human rights.

- Many migrant and refugee women are cautious about reporting violence or addressing this issue publicly because they are:

- fearful of having their communities vilified (e.g. through racism and stereotyping);

- concerned about the pathologising of ‘culture’ that can occur when violence against migrant and refugee women is addressed by mainstream groups (which shifts the focus from the violence to the specific culture of the perpetrator and victim/survivor);

- reluctant to seek assistance from the police due to experiences of racism by authorities, a history of fear and distrust of authority figures and, in some cases, experiences of violence by authorities in their home country; or

- concerned that they will be stigmatised by their communities.

- Limited statistical data and research studies are available on the prevalence and nature of violence against migrant and refugee women.

- The National Plan fails to accommodate and adequately address the specific needs and experiences of migrant and refugee women, including those that arise from the intersections of gender, culture, religion and language.

- The emphasis on provision of mainstream services has led to a lack of resources and services that meet the particular, and often complex, needs of migrant and refugee women.

- Grassroots women’s organisations should be supported and resourced to undertake research and provide specific, rights-based services for migrant and refugee women. Migrant and refugee women who are victims/survivors of violence frequently face difficulties in accessing services and support (e.g. shelters and safe houses) due to the lack of culturally and linguistically trained staff, and the lack of culturally appropriate services, policies and programs.

- Migrant and refugee women in rural, regional and remote areas face additional barriers in accessing culturally and linguistically appropriate information, services and support to address violence. For example, due to geographic isolation, there are a lack of services available for migrant and refugee women and, where services do exist, they lack culturally suitable infrastructure and procedures.

- There is limited access linguistically appropriate information about violence against women and interpreters, which impedes the ability of migrant and refugee women to understand their rights and identify avenues of redress.

- Migrant and refugee women experiencing domestic violence would benefit from having family members being allowed into Australia to support victims/survivors.

- Experiences of domestic and family violence are exacerbated for women coming from war-torn countries in Africa and other situations of conflict. The cumulative impact of traumas can undermine the resilience of migrant and refugee women and encumber their capacity to access services and support.

- Many service providers do not have the training required to address the specific re-settlement needs of migrant and refugee women and, therefore, a high level of failure is evident in the resettlement of migrant and refugee women. The lack of cultural competency is particularly apparent in respect of child protection and domestic and family violence issues. For example, ensuring the safety of children, but not women, perceived to be in violent family situations.

- There is a concern that criminalising forced marriage will push this issue underground and undermine the best interests of children in those families.

- The issues of trafficking, forced labour and slavery were also reported as key issues for migrant and refugee women.

- Many migrant and refugee women who are victims/survivors of domestic and family violence fear reprisal and loss of work if they were to raise that violence with their employer.

- The visa status of some women (e.g. students or dependents of male students) makes it difficult for them to leave violent situations or seek support. The family violence provision in the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) allows for spousal visas and protections, but there are many migrants, single mothers and students who do not satisfy the Act’s family violence criteria and are left unprotected.

Chapter 7: Violence against women with disability roundtables49

On 18 April 2012, the Australian Human Rights Commission, Women With Disabilities Australia, and Women With Disabilities Victoria co-hosted a national roundtable on violence against women with disability. The roundtable, which was held at Women’s Health Victoria in Melbourne, was attended by approximately

22 people, including women with disability representing Disabled People’s Organisations, domestic violence support service providers, mental health workers, academics, a representative from the Office of the Public Advocate Victoria, and a female parliamentarian with disability from South Australia.

Key issues for women with disability identified by roundtable participants and by participants in other general community roundtables are outlined below.

- Women with disability experience higher levels of violence in Australia compared to women without disability and are more likely to experience violence in residential and institutional settings.

- Limited data and research is available on the prevalence and nature of violence against women with disability.

- Women with disability are often subjected to predatory and violent behaviour by their carers and many are afraid to report incidents because of a fear of reprisal or lack of confidence in authorities and the justice system.