OPCAT in Australia Consultation Paper (2017)

OPCAT in Australia Consultation Paper

Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 What is OPCAT?

- 3 The NPM model

- 4 Key issues for consideration

- 5 Consultation with civil society

1 Introduction

-

The Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT) provides for independent inspections of all places of detention in the jurisdictions that ratify and implement it .[1] On 9 February 2017, the Australian Government announced it intends to ratify OPCAT by December 2017 working closely with states and territories.[2]

-

While the Australian Government has outlined some of the key features of how it intends OPCAT to operate in Australia, there remain many details still to be determined. The Government has explicitly provided for a period of consultation with key stakeholders.

-

Accordingly, the Commonwealth Attorney-General has asked the Human Rights Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission to conduct consultations with civil society to provide advice back to the Australian Government on views of how OPCAT should be implemented within Australia.

-

This Consultation Paper (the Paper) aims to help those with an interest in conditions of places of detention to participate in the process that will determine how OPCAT is implemented in Australia. Primarily, the Commission encourages input from those in the civil society sector with particular experience and expertise regarding conditions of detention, such as relevant medical professionals, lawyers, social workers, academics, human rights bodies, religious and faith based groups and organisations representing people with lived experience of detention.

-

While the focus of the Commission’s consultation is to facilitate the participation of civil society in OPCAT implementation, the Commission also welcomes the views of representatives from federal, state and territory governments who will be, or who are currently involved with, the OPCAT implementation process in their jurisdiction (including corrective services, oversight bodies, justice policy specialists etc).

-

While OPCAT involves both international and domestic inspection processes, the primary focus of this Consultation Paper is on the domestic process.

-

The Commission is interested in receiving community views. The Commission will analyse the feedback it receives and make findings and recommendations that takes into account the material received.

-

The Commission anticipates that there will be two phases in this work. The first will constitute the Commission’s analysis of the key issues that the Australian Government will need to resolve before it ratifies OPCAT by December 2017. To this end, the Commission intends to communicate informally with the Australian Government any key recommendations in or around September 2017.

- The second phase of the Commission’s work on OPCAT will involve a more detailed analysis of the much larger list of issues that all Australian governments will need to resolve in the implementation period in the years following ratification. The Commission plans to prepare a more detailed report, which will cover this broader range of issues, to be published in 2018. The Commission is open to undertaking a second round of community and stakeholder consultation in this second phase of its work.

2 What is OPCAT?

-

OPCAT is an international human rights treaty that aims to prevent ill treatment in places of detention through the establishment of a preventive-based inspection mechanism.

-

OPCAT is an optional protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT).[3] As a treaty in its own right, OPCAT is open to signature and ratification. Australia signed OPCAT on 19 May 2009. Australia ratified CAT in 1989.

-

Under CAT, Australia must do a range of things, including:

-

prevent torture

-

prevent other acts of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment

-

ensure that education and information regarding the prohibition against torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment are fully included in the training of all people involved in the arrest, custody, interrogation, detention or imprisonment of any individual;

-

regularly review interrogation rules, instructions, methods and practices to prevent torture

-

periodically report to the UN Committee Against Torture on measures taken to implement the obligations contained in the treaty.

-

-

OPCAT supplements these obligations by requiring countries to introduce a system of regular inspection visits to all places where people are deprived of their liberty in order to prevent torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

-

The ratification of OPCAT would not establish further substantive obligations to those contained in CAT. Rather, ratification would introduce to Australia a greater level of transparency and accountability for the treatment of people who are deprived of their liberty in detention facilities.

-

OPCAT requires monitoring system of places of detention to occur through two complementary and independent bodies:

-

the National Preventive Mechanism (NPM),the domestic Australian entity or network responsible for inspections; and

-

the UN Sub-committee on the Prevention of Torture (SPT), the UN body of independent experts responsible for conducting visits to places of detention in jurisdictions that have ratified OPCAT and provide guidance to NPMs to assist in the performance of their duties.

-

2.1 National Preventive Mechanism

-

The NPM is a domestic oversight and inspection mechanism, designated by Australia, which would conduct regular visits to places of detention in order to prevent torture and other forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.[4]

-

The NPM takes a preventive rather than a reactive complaints-driven approach. Through regular and unannounced visits, the NPM identifies problematic detention issues before ill treatment occurs or before it escalates. The NPM can then seek to address such problems through regular dialogue with detention authorities.

-

The preventive and collaborative approach is designed to increase confidence in the detention environment. The NPM should seek to build trust with detention authorities and work collaboratively to prevent torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

-

The work of the NPM is distinct from internal compliance practices and investigations instigated in response to a specific problem or complaint. The NPM complements, rather than replaces, existing oversight systems and should work with other key stakeholders to fulfil its mandate.

-

The NPM is designed to meet the particular legal and administrative processes in a country. It can consist of one or several bodies, which have a mandate to visit all places of detention within the jurisdiction.[5] This includes any form of detention or imprisonment in a public or private custodial setting that a person is not allowed to leave at will by order of any judicial, administrative or other authority.[6]

-

The NPM can choose to prioritise particular places of detention. By initially prioritising certain places of detention, the NPM can progressively ensure that there is appropriate coverage and arrangements in place. This process enables the NPM to learn from implementation and share practices and experiences in order to improve the overall inspection framework.

- NPM bodies must have a legislative mandate and be provided resources to fulfil that mandate. OPCAT sets out the following requirements for the NPM:

- functional independence and independence of their personnel (article 18 (1))

- necessary resources for functioning (article 18(3))

- a mandate to undertake regular preventive visits (article 19 (a))

- the power to make recommendations (article 19(b)); authorities must examine recommendations and enter into dialogue with the NPM on implementation measures (article 22)

- access to information concerning the number of people detained and places of detention (article 20(a))

- access to information on treatment and conditions of people in detention (article 20(b))

- access to places of detention (article 20(c))

- the right to conduct private interviews with detained people and others (article 20(d))

- the liberty to choose places visited and people interviewed (article 20(e))

- the requirement that confidential information should be privileged (article 21(2));

- experts with required capabilities and professional knowledge, gender balance and adequate representation of ethnic and minority groups (article 18 (2))

-

In addition to the above requirements, the SPT’s guidance is that it would be beneficial for the NPM to:

-

publicise opinions and findings including through annual and thematic reports

-

make submissions to governments and parliament regarding proposed legislation and policies that are relevant to its mandate

-

maintain regular contact with the SPT

-

contribute to reports and follow up on recommendations made by United Nations human rights bodies.[7]

-

- The NPM is to be established within one year of ratification; however, this decision can be postponed for a period of up to three years.[8] A country can, if it chooses, extend the postponement period for a further two years after consulting with the SPT and the Committee against Torture.[9]

2.2 Sub-committee on the Prevention of Torture

-

The SPT is a UN body consisting of 25 international experts. SPT members are chosen with diverse experience from within the field of administration of justice, including criminal law, prison or police administration and, increasingly, from those with medical expertise including doctors, psychologists and psychiatrists. SPT members serve in their personal capacity and are required to be independent and impartial.[10]

-

The SPT has a mandate to:

-

visit places of detention and make recommendations regarding the protection of people in detention

-

advise countries on the establishment of NPMs and make recommendations on strengthening their capacity

-

maintain contact with NPMs to offer training and technical assistance and to provide advice on the protection of people in detention

-

cooperate with relevant UN bodies and other institutions for the prevention of torture.[11]

-

-

Under OPCAT, Australia would undertake to allow the SPT to access places of detention as part of a regular program of visits. Given current practice, the SPT can be expected to conduct a visit to Australia once every seven to ten years.

-

The Commission agrees with the view of the Australian Government that no new federal legislation is needed to authorise SPT visits.[12]

-

In order for the SPT to fully realise its mandate under OPCAT, the SPT has devised four types of visits: regular country visits, follow-up visits, NPM advisory visits or OPCAT advisory visits. In countries similar to Australia, SPT visits have largely focused on improving the capacity of the NPM through technical assistance.

-

During a visit, the SPT will engage with authorities at all levels who are responsible for detention in order to develop an understanding of the legal and practical framework of the detention environment. The SPT will meet with governments, detention authorities, civil society and the NPM itself. The SPT will also conduct visits to a variety of places of detention, usually in the company of the NPM.

- The SPT maintains strict confidentiality regarding its findings and recommendations. Following a visit, the SPT will provide a confidential report to the Australian Government. The country report on Australia may only be made public with the express permission of the Australian Government.[13]

3 The NPM model

-

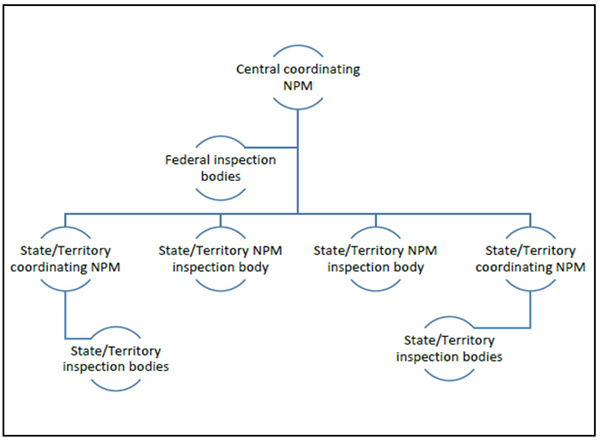

The Commonwealth Attorney-General has indicated that multiple bodies from the federal, state and territory governments will be responsible for inspection responsibilities.

-

The work of the various inspection bodies will be supported by a national coordinating mechanism responsible for coordination and capacity building. The Attorney-General has announced that the Commonwealth Ombudsman would perform the national coordinating function.[14]

-

The national coordinating mechanism can facilitate the sharing of best practices, ensure inspection standards are harmonised, and identify ways of streamlining inspection processes. The national coordinating mechanism will have residual inspection powers for places of detention not covered by other NPM bodies.[15]

-

In preparing this Paper, the Commission invited the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s office to comment on its likely role under OPCAT. It acknowledged that ‘crucial to the successful implementation of the OPCAT framework in Australia will be the coordination and streamlining of the roles and practices of the network of agencies with an oversight role.’[16] It therefore views its position as NPM Coordinator as one of collaboration and facilitation.

-

The Commonwealth Ombudsman will promote a collegiate approach between the NPM and other agencies including the Commission, to identify systemic issues and highlight areas of concern. Working with these agencies the Commonwealth Ombudsman will contribute to a shift away from a reactive, to a nationally consistent preventative inspection methodology, constructed on best practice both domestically and abroad.

-

The Commonwealth Ombudsman will also facilitate regular discussions within States and Territories and between them to share knowledge, increase rapport between these agencies and identify themes for ongoing research and consultation. The Commonwealth Ombudsman will retain its own inspection function at the Commonwealth level, allowing it to benefit from the combined NPM learnings and to continuously contribute to pragmatic solutions and best practice. Finally, the Commonwealth Ombudsman will initiate informative sessions to promote the work of the NPM to detaining bodies and civil society alike.

-

The Australian Government has decided to vest the NPM function across multiple federal, state and territory bodies, as distinct from a single NPM covering all Australian places of detention. This mixed model is based on the fact that detention in Australia is undertaken by all of the jurisdictions that make up the Commonwealth, but most places of detention are state and territory facilities.

-

This mixed model also enables states and territories to harness and adapt existing inspection mechanisms. Some states and territories may choose to designate more than one inspection body, in which case they may also choose to designate a coordinating mechanism for that jurisdiction.

-

Where existing mechanisms are designated as NPM bodies, their mandates and practical capabilities should be expanded to meet OPCAT requirements where necessary. New bodies may be established where existing coverage is insufficient.

- There are a number of alternate ways of arranging the NPM function across the Commonwealth, State and Territory jurisdictions. The following diagram shows how the Government’s proposed NPM model might operate in Australia.

Figure 1 – Potential NPM model for Australia

4 Key issues for consideration

- OPCAT will require the development of a comprehensive inspection framework for places of detention in Australia. This section outlines some of the opportunities and challenges that may arise in implementing OPCAT.

4.1 Stocktake of places of detention

-

At the outset, an assessment of existing inspection mechanisms will need to occur in order to identify what mechanisms are currently in place, the extent to which these meet OPCAT requirements and any gaps in coverage. Such an assessment is likely to also identify any duplication or fragmentation of inspection functions.

-

Adapting existing mechanisms for OPCAT will also likely require changes to inspection methodologies. Appropriate training will need to be provided to staff who undertake inspections. Separate NPM units may need to be established within existing mechanisms in order to ensure functional independence from other activities. Further mechanisms to ensure transparency, such as through public reporting, may also be required to supplement existing procedures for existing inspection mechanisms.

-

Each jurisdiction in Australia will need to have an understanding of the current status of inspection mechanisms within their control. A stocktake or audit of such mechanisms is routinely undertaken in the lead up to, or upon ratification of, OPCAT. This work has already commenced in some jurisdictions. In April 2017, for example, the Victorian Ombudsman announced an investigation into the practical changes required in Victoria to implement OPCAT.[17]

- The following case study shows how this stocktake has been undertaken by the Australian Human Rights Commission, specifically in relation to the juvenile detention context.

National Children’s Commissioner – Project on OPCAT and juvenile detention in Australia

In 2016, the National Children’s Commissioner, Megan Mitchell, conducted a national investigation into OPCAT and how it relates to children and young people detained in youth justice detention facilities in Australia.

The project included a stocktake of current oversight, complaints and reporting arrangements across the jurisdictions, an analysis of their adequacy in meeting the OPCAT requirements, and an identification of opportunities for improvements nationally over time.

The Children’s Commissioner visited youth justice centres in each state and territory. Information was also gathered through formal requests to governments, expert roundtables, submissions and through desktop research.

The findings and recommendations were published in the Children’s Rights Report 2016, tabled in the Australian Parliament on 1 December 2016.[18] The report identified gaps in coverage and concluded that while most jurisdictions have bodies which met some of the NPM criteria, no jurisdiction met all of the criteria. The report also highlighted good practices that could be adopted by other jurisdictions.

4.2 Definitional issues – what does OPCAT cover?

-

There are two sets of issues on which definitional clarity will be required to implement the obligations under OPCAT:

-

Understanding the conduct to which OPCAT obligations apply – i.e. torture, as well as inhuman, cruel or degrading treatment; and

-

Understanding the settings in which it applies – i.e. what constitutes a place of detention.

-

-

The term ‘torture’ has a specific definition under Article 1 of CAT:

the term "torture" means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.

-

In Australia, where robust legal and criminal justice frameworks exist, the general risk of torture is low. However, OPCAT also prohibits other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment that falls short of the legal definition of torture.

-

What constitutes ‘cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment’ is not strictly defined in international human rights law. The Australian Government has defined what it considers to be ‘cruel or inhuman treatment or punishment’ in s 5 of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) to include an act or omission by which

(a) severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person; or

(b) pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person so long as, in all the circumstances, the act or omission could reasonably be regarded as cruel or inhuman in nature.

-

The UN Human Rights Committee considers it unnecessary to exhaustively list or ‘draw up sharp distinctions’ between different kinds of punishment or treatment, rather ‘the distinctions depend on the nature, purpose and severity of the treatment applied’.[19] The Committee also offers little guidance in its jurisprudence; when finding there has been a breach the Committee rarely explains into which category of cruel, inhuman or degrading the conduct falls. Whether the treatment or punishment meets the threshold will depend on the individual circumstances of the case in question. While a question of degree, inhuman or degrading treatment will be severe. The Committee has, for example, noted that ‘for punishment to be degrading, the humiliation or debasement involved must exceed a particular level and must, in any event, entail other elements beyond the mere fact of deprivation of liberty’.[20]

-

Article 4.1 of the Protocol defines a place of detention to include where a person is deprived of his or her liberty ‘either by virtue of an order given by a public authority or at its instigation or with its consent or acquiescence’. Article 4.2 defined ‘deprivation of liberty’ to include

any form of detention or imprisonment or the placement of a person in a public or private custodial setting which that person is not permitted to leave at will by order of any judicial, administrative or other authority.

- Rather than focusing on torture, OPCAT can be used as a vehicle to implement best practice within detention settings in order to improve existing systems and prevent conduct that constitutes ill-treatment. This approach has been recognised in similar countries including the United Kingdom, Germany and Netherlands.

4.3 Progressive implementation of OPCAT

-

Under OPCAT, the NPM has oversight and inspection responsibilities over a non-exhaustive list of places of detention.[21] Concerns have been raised as to whether NPM bodies in Australia will be ready to inspect all possible places of detention upon ratification.

-

Although the mandate under OPCAT is comprehensive, the NPM bodies set their own priorities and are not expected to address every issue arising within places of detention immediately upon ratification. The Government is likely to invoke Article 24 of OPCAT to provide an initial 3-year implementation period for the NPM.

-

The SPT has recognised that the development of the NPM includes a process of refinement and incremental improvement:

[NPMs] should try to find and put forward creative solutions that might address an issue over time in an incremental fashion... the national preventive mechanism should develop concrete long- and short-term strategies in order to achieve the maximum impact on problems and challenges relevant to its mandate in the local context. Activities and their outcomes should be monitored and assessed on an ongoing basis and the lessons learned should be used to develop the practices of the mechanism.[22]

-

Australia can progressively implement OPCAT by establishing an NPM with a broad mandate but with an initial limited focus. The NPM can then develop long-term strategies to ensure full coverage. The initial operation of the NPM can be used to identify gaps in inspection processes in order to expand coverage as the system matures.

-

Progressive implementation has been adopted by other countries as a practical method of implementing OPCAT. In Germany, for instance, the NPM initially limited its inspection activities to certain types of detention (prisons, police units, psychiatric clinics, immigration detention), but gradually expanded its activities as the system developed and more resources became available.[23]

-

If such an approach is adopted, the Australian Government would be obliged to demonstrate to the SPT that it is meeting the obligations under OPCAT in good faith.

-

Accordingly, the NPM would need to have robust planning in place for how it will expand the scope of coverage over time, and demonstrate its processes for continually reviewing the pace at which this expanded scope is achieved. One common way of considering whether this progressive approach is sufficiently rigorous would be to establish that implementation is articulated in a manner that is based on SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-based).

-

One approach that has been adopted in some countries is for the NPM to develop working practices that seek to progressively address issues arising within the detention environment. The NPM may consider taking an annual thematic focus which seeks to address a particular systemic issue that occurs across detention environments.

- The following case study shows how New Zealand undertook a project to address a systemic issue that was identified by the NPM.

New Zealand NPM - Project on seclusion and restraint in the detention context

The New Zealand NPM and the SPT (during a country visit) found that the reporting and documentation of seclusion and restraint in New Zealand were not consistent across detention environments, with some powers being used on a more routine basis than provided for in legislation.

As a result of these findings, the New Zealand NPM is undertaking a comprehensive study of seclusion and restraint policies and practices within detention facilities. The project aims to document the current use of seclusion and restraint across all detention facilities in order to identify a preferred practice.

The project is funded by the UN Special Fund of OPCAT. The Special Fund is managed by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and is available to countries that have been visited by the SPT and who are seeking support to implement SPT recommendations.

The project is led by the central coordinating NPM body, the New Zealand Human Rights Commission, in close consultation with other NPM bodies and stakeholders. The coordinating NPM is undertaking a desktop stocktake of current policies, practices, guidelines and data on the use of seclusion and restraint across detention environments.

An independent consultant has been employed for the project to provide expertise and to conduct inspections across detention facilities.

The coordinating NPM will publish a thematic report, which will be submitted to the New Zealand Government. The thematic report will be accompanied by a monitoring plan to oversee the implementation of recommendations.

4.4 Scope of the role of the NPM

-

The Commission will work collaboratively to support the Commonwealth Ombudsman in its role as NPM Co-ordinator. Coordination of the various bodies involved in OPCAT – that is, federal, state and territory government bodies, as well as civil society – could include:

-

providing a focal point to consider best practices in each jurisdiction, to foster continuous improvement

-

developing national standards to provide guidance to all places of detention and inspection mechanisms

-

identifying gaps and duplications in order to provide efficiencies within inspection processes

-

coordinating and facilitating the training of NPM bodies and detention authorities

-

raising awareness of the NPM within governments, parliaments and within detention environments

-

consulting with the SPT and other relevant United Nations human rights bodies in order to develop the NPM.

-

-

It is also worth considering what mechanisms the national coordinating mechanism should put in place to consult with groups who are particularly affected by the OPCAT obligations due to the specific vulnerabilities that they experience in different detention environments. This would include considering whether specific consultative mechanisms are put in place in relation to:

-

Prisoners

-

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

-

Children and young people

- Persons with a disability.

-

4.5 Coordination between federal and state/territory mechanisms

-

Related to this challenge, will be establishing effective working relationships between the national level coordination mechanism, and the various state and territory mechanisms.

-

It is likely that each state and territory will adopt different approaches to coordinate their OPCAT requirements. Smaller states and territories, such as Tasmania and the Northern Territory, may opt for a single mechanism, whereas larger states may opt for multiple mechanisms in different service areas which are then coordinated at the state level through a central coordination mechanism.

-

The national coordination mechanism will need to establish how it engages with individual mechanisms as well as any coordination mechanisms at the state and territory level.

-

The model that the Commonwealth has identified is driven by a principle that states and territories will primarily be responsible for inspection processes within their jurisdictions. As a result, the federal coordinating mechanism is not likely to be the agency that undertakes the majority of inspections at the state and territory level.

- For this reason, the national coordinating mechanism will need to establish working methods that ensure that it is satisfied at the adequacy of the individual inspection frameworks at the state and territory level, and to ensure that they are compliant with the requirements of OPCAT.

5 Consultation with civil society

-

The model announced by the Australian Government gives distinct functions to those bodies with an NPM designation. The Government also explicitly recognised the importance of other stakeholders in contributing to the success of OPCAT – especially government bodies and civil society organisations that undertake inspections.

-

The Government has asked the Australian Human Rights Commission to liaise with civil society, both in OPCAT’s implementation and operational phases, so that civil society can contribute as effectively as possible to improving conditions of detention.

-

The Commission is seeking input from individuals and organisations in two ways.

-

First, the Commission invites written responses to the guideline questions posed at part 5.1 of this Consultation Paper. Responses to the paper should be emailed to humanrights.commissioner@humanrights.gov.au by 21 July 2017.

Please note that when making a submission, you are indicating that you have read and understood the Commission’s Submission Policy, which can be found at https://www.humanrights.gov.au/submission-policy.

-

Secondly, the Commission will host a series of consultation roundtables in select capital cities seek views on the development and establishment of NPM bodies in each jurisdiction.

- The roundtables will draw on the expertise of relevant stakeholders to inform how OPCAT should be implemented in Australia.

5.1 Questions for discussion

- The questions below are intended to help direct stakeholder attention to some of the key issues being considered, or to be considered, regarding how OPCAT should operate in Australia. Stakeholders should feel free to answer some, all or none of these questions. They may also provide input on other issues relevant to OPCAT, which do not arise directly in the questions below.

1. What is your experience of the inspection framework for places of detention in the state or territory where you are based, or in relation to places of detention the Australian Government is responsible for?

Stakeholders may wish to comment on issues such as:

- whether there are any crucial gaps or overlap in the inspection framework

- the staffing or relevant professional expertise you consider important for inspections, such as the need for mental health professionals to be included on visiting teams

- significant legislative, regulatory or policy changes that would be required for a relevant inspection body for it to be OPCAT compliant.

2. How should the key elements of OPCAT implementation in Australia be documented?

Noting that the Australian Government has indicated that it does not intend to create new legislation to implement OPCAT into federal law, stakeholders may wish to comment on issues such as:

- whether it is necessary to have a formal agreement (or other such document) that sets out the core elements of how OPCAT will operate

- whether the roles of the various government and non-government bodies involved in OPCAT should be documented and, if so, how this should take place.

3. What are the most important or urgent issues that should be taken into account by the NPM?

Stakeholders may wish to comment on issues such as:

- specific places of detention that are of immediate concern

- broader systemic issues that the NPM should focus on, such as indefinite detention of people with cognitive disabilities; or

- current practices on seclusion and restraint.

4. How should Australian NPM bodies engage with civil society representatives and existing inspection mechanisms (eg, NGOs, people who visit places of detention etc)?

Stakeholders may wish to comment on issues such as how:

- best to arrange regular consultation and liaison

- civil society representatives can identify problems in places of detention and how they can work with the NPM process to develop solutions.

5. How should the Australian NPM bodies work with key government stakeholders?

Stakeholders may wish to comment on issues such as:

- how the NPM could engage with parliament, government human rights bodies and detaining authorities

- how the NPM could should engage with the SPT

- how communication across the different state and territory NPMs could be facilitated and co-ordinated

- whether specific processes should be developed to address the needs of vulnerable groups of people in detention.

6. How can Australia benefit most from the role of the SPT?

7. After the Government formally ratifies OPCAT, how should more detailed decisions be made on how to apply OPCAT in Australia?

Note that the Australian Government has indicated that it intends to implement OPCAT over a three-year period after ratification in December 2017. It is anticipated that more detailed decisions will be made during that period about how OPCAT will operate in Australia.

5.2 Outcome of the consultation process

-

At the conclusion of the consultation period, the Commission will analyse the written responses received and the discussion at the consultation roundtables and report back to government in an interim report in or around September 2017, with a final report to be published in 2018.

- You can access up-to-date information about the Commission’s work on OPCAT on the Commission’s website at our Consultation Page https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/rights-and-freedoms/opcat-consultation-page and our OPCAT page https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/rights-and-freedoms/projects/optional-protocol-convention-against-torture-opcat

[1] Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 4 February 2003, 2375 UNTS 237 (entered into force 22 June 2006). At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPCAT.aspx (viewed 21 April 2017).

[2] Commonwealth Attorney-General, ‘Media Release - Improving oversight and conditions in detention’, 9 February 2017. At https://www.attorneygeneral.gov.au/Mediareleases/Pages/2017/FirstQuarter/Improving-oversight-and-conditions-in-detention.aspx (viewed 7 April 2017).

[3] Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 10 December 1984, 1465 UNTS 85 (entered into force 26 June 1987). At https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-9&chapter=4&clang=_en (viewed 21 April 2017).

[4] Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 4 February 2003, 2375 UNTS 237 (entered into force 22 June 2006), article 3. At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPCAT.aspx (viewed 21 April, 2017).

[5] Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 4 February 2003, 2375 UNTS 237 (entered into force 22 June 2006), article 3. At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPCAT.aspx (viewed 21 April 2017).

[6] Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 4 February 2003, 2375 UNTS 237 (entered into force 22 June 2006), article 4 (2). At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPCAT.aspx (viewed 21 April 2017).

[7] Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Analytical assessment tool for national preventive mechanisms, UN Doc CAT/OP/1/Rev.1 (25 January 2016). At http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/OPCAT/CAT-OP-1-Rev-1_en.pdf (viewed 21 April 2017).

[8] Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 4 February 2003, 2375 UNTS 237 (entered into force 22 June 2006), article 17, 24. At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPCAT.aspx (viewed 21 April 2017).

[9] Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 4 February 2003, 2375 UNTS 237 (entered into force 22 June 2006), article 24. At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPCAT.aspx (viewed 21 April 2017).

[10] Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 4 February 2003, 2375 UNTS 237 (entered into force 22 June 2006), article 5. At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPCAT.aspx (viewed 21 April 2017).

[11] Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 4 February 2003, 2375 UNTS 237 (entered into force 22 June 2006), article 11. At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPCAT.aspx (viewed 21 April 2017).

[12] As a matter of policy, Australia currently offers a standing invitation to all Special Procedures of the United Nations who wish to conduct a country visit (see Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Standing Invitations, at http://spinternet.ohchr.org/_Layouts/SpecialProceduresInternet/StandingInvitations.aspx (viewed 21 April 2017)). Accordingly, once OPCAT has been ratified there is no legal obstacle to inspections being carried out by the SPT as the standing invitation will apply to any inspection of any facility, unannounced or otherwise. In 2016, for example, Australia facilitated country visits by four Special Rapporteurs, with the full support of state and territory governments (see Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Country and visits of Special Procedures. At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/SP/Pages/CountryandothervisitsSP.aspx (viewed 21 April 2017).

[13] Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, opened for signature 4 February 2003, 2375 UNTS 237 (entered into force 22 June 2006), article 16. At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPCAT.aspx (viewed 21 April 2017).

[14] Commonwealth Attorney-General, ‘Media Release - Improving oversight and conditions in detention’, 9 February 2017. At https://www.attorneygeneral.gov.au/Mediareleases/Pages/2017/FirstQuarter/Improving-oversight-and-conditions-in-detention.aspx (viewed 7 April 2017).

[15] Association for the Prevention of Torture, Establishment and Designation of National Preventive Mechanisms (2006) p 94. At http://www.asiapacificforum.net/media/resource_file/Guide_Establishment_Designation_NPMs.pdf (viewed 21 April 2017).

[16] Naylor, B., Harrison, L., Dussuyer, I., & Kessel, R. (2014, May). Monitoring Closed Environments: The Role of Oversight Bodies. Retrieved March 6, 2017, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bronwyn_Naylor/publication/263679099_Monitoring_Closed_Environments_The_Role_of_Oversight_Bodies_-_WP_3_Applying_Human_Rights_Legislation_in_Closed_Environments_A_Strategic_Framework_for_Managing_Compliance/links/0046353ba9b60bb78f000000.pdf

[17] Victorian Ombudsman, Media Release: Victoria can protect human rights by acting on OPCAT: Ombudsman. (3 April 2017) At https://www.ombudsman.vic.gov.au/News/Media-Releases/Media-Alerts/Victoria-can-protect-human-rights-by-acting-on-OPC (viewed 2 May 2017).

[18] Australian Human Rights Commission, Children’s Rights Report 2015 (2016). At https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/childrens-rights/publications/childrens-rights-report-2016 (viewed 21 April 2017).

[19] United Nations Human Rights Committee, CCPR General Comment No. 20: Article 7 Prohibition of Torture, or Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment) (10 March 1992): para 4. At http://www.refworld.org/docid/453883fb0.html (viewed 9 May 2017).

[20] Vuolanne v Finland, Communication No. 265/1987, UN Doc Supp No. 40 (A/44/40) at 311 (1989), at para 9.2. At http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/undocs/session44/265-1987.htm (viewed 9 May 2017(

[21] Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Compilation of SPT Advice in response to NPMs requests. At http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/OPCAT/CompilationSPTAdvices.doc (viewed 21 April 2017).

[22] Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Analytical assessment tool for national preventive mechanisms, UN Doc CAT/OP/1/Rev.1 (25 January 2016). At http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/OPCAT/CAT-OP-1-Rev-1_en.pdf (viewed 21 April 2017).

[23] National Agency for the Prevention of Torture, Annual Report 2015 (2015). At http://www.nationale-stelle.de/index.php?id=74&L=1 (viewed 21 April 2017).

![Mr Nauroze Anees v Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Home Affairs) [2019] AusHRC 133](/sites/default/files/styles/news_thumbnail/public/2020-03/2019_AusHRC_133_Redacted-_500px.jpg?itok=C7Xp7ads)