Native Title Report 2008 - Chapter 5

Archived

You are in an archived section of the website. This information may not be current.

This page was first created in December, 2012

Native Title Report 2008

Chapter 5

Indigenous peoples and climate change

![]() Download in PDF

Download in PDF

![]() Download in Word

Download in Word

- 1 Overview of key climate change issues for Australia’s Indigenous peoples’

- 2 The Indigenous Estate – ‘our’ greatest asset?

- 3 The climate change challenge

- 4 Opportunities from climate change

- 5 Indigenous Engagement with Policy Formulation

- 6 Close the Gap – Join the Dots

- Recommendations

Climate change has been regarded as a diabolical policy problem globally. The potential threat to the very existence of Indigenous peoples is compounded by legal and institutional barriers raise distinct challenges for our cultures, our lands and our resources.[1] More seriously, it poses a threat to the health, cultures and livelihoods of Indigenous peoples both here in Australia and around the world.

The importance of culture and its relevance to Indigenous people’s relationship to our lands, is not completely understood and acknowledged in Australia. This is evidenced by the fact that governments continue to develop Indigenous land policy in isolation from other social and economic areas of policy. This is apparent in the development of climate change policy which has generally fallen on the shoulders of government departments responsible for climate change and the environment, absent of involvement from those departments responsible for Indigenous affairs or the social indicators such as health and housing.

Understanding the significance of the impacts of climate change on Indigenous peoples requires an understanding of the intimate relationships we share with our environments: our lands and waters; our ecosystems; our natural resources; and all living things is required. Galarrwuy Yunipingu expresses this relationship:

I think of land as the history of my nation. It tells me how we came into being and what system we must live. My great ancestors, who live in the times of history, planned everything that we practice now. The law of history says that we must not take land, fight over land, steal land, give land and so on. My land is mine only because I came in spirit from that land, and so did my ancestors of the same land...My land is my foundation.[2]

Professor Mick Dodson has also provided an explanation of the relationship between Aboriginal people and our ‘country:

The word country best describes the entirety of our ancestral domains. All of it is important – we have no wilderness. It is place that also underpins and gives meaning to our creation beliefs – the stories of creation form the basis of our laws and explain the origins of the natural world to us – all things natural can be explained. It is also deeply spiritual. It is through our stories of creation we are able to explain the features of our places and landscape. It is the cultural knowledge that goes with it that serves as constant reminders to us of our spiritual association with the land and its places. Even without the in depth cultural knowledge, knowing country has spiritual origins makes it all the more significant and important to us.

Country for us is also centrally about identity. Our lands our seas underpin who we are. Where we come from. Who our ancestors are. What it means to be from that place from that country. How others see and view us. How others identify us. How we feel about each other. How we feel about our families and ourselves. Country to us is fundamentally about our survival as peoples. [3]

The words of Yunipingu and Dodson highlight the fact that our land is fundamental to our health and well-being. Indigenous law and life originates in and is governed by the land. Indigenous identity and sense of belonging comes from our connection to our country. In contrast to non-Indigenous understandings of land as a commodity, land is our ‘home’.

The responsibilities that go with our home do not allow us to sell up or move on when it is no longer tenable. The land is our mother, it is steeped in our culture, and we have a responsibility to care for it now and for generations to come. This care in turn sustains our lives – spiritually, physically, socially and culturally - much like the farmer who lives off the land.

National climate change policy development is developing rapidly in Australia.[4] Despite the Government’s expectation that the Indigenous estate will provide economic outcomes from carbon markets[5], Indigenous stakeholders have largely been left out of the debate and there is little analysis available on the direct or indirect impacts of climate change on Indigenous peoples in Australia.

However, at the local level, there is a significant amount of discussion and project development by Indigenous stakeholders who are concerned about the impacts of climate change on their communities. We are particularly concerned that Indigenous lands and waters will be a key element in the national policy response to climate change, yet we have not been engaged in the domestic or international policy debates.

1 Overview of key climate change issues for Australia’s Indigenous peoples’

The International Working Group for Indigenous Affairs stress that ‘for Indigenous peoples around the world, climate change brings different kinds of risks and opportunities, threatens cultural survival and undermines Indigenous human rights’.[6] Climate change, will specifically affect the way Indigenous people exercise and enjoy our human rights at a time when the human rights of all people are being threatened.

In Australia these risks and opportunities will also be diverse, and in some regions are already being experienced.[7] Problems that Indigenous Australians will encounter include:

- people being forced to leave their lands particularly in coastal areas. Dispossession and a loss of access to traditional lands, waters, and natural resources may be described as cultural genocide; a loss of our ancestral, spiritual, totemic and language connections to lands and associated areas.

- the migration of Indigenous peoples from island and coastal communities and those communities dependent on our inland river systems to relocate to larger islands, mainland Indigenous communities or urban centres.

- no longer being able to care for country and maintain our culture and traditional responsibilities to land and water management. Such a disconnect will result in environmental degradation and adverse impacts on our biodiversity and overall health and well-being.

- in tropical and sub-tropical areas, an increase in vector-borne, water-borne diseases (such as malaria and dengue fever).

- a disruption to food security, including subsistence hunting and gathering livelihoods and biodiversity loss, increase in the need for and the cost of food supply, storage and transportation, and an increase in food-borne diseases.

- the risk of being excluded from the establishment and operation of market mechanisms that are being developed to address environmental problems, for example water trading, carbon markets and biodiversity credit generation.

The issues that Indigenous people in Australia will face are evidenced and exacerbated by climatic changes including:

- the increased number and intensity of cyclones and storms, leading to flash floods

- the rising sea levels and inundation of fresh water supplies by salt water

- coastal erosion and changes to ecosystems, such as mangrove systems

- the bleaching and sustainability of our reefs

- the drying up of water systems that were once never empty

- the frequency and intensity of bushfires and drought and desertification

- the changing migratory patterns of our sea animals and birds

- the dying out of particular wildlife and plant life in our ecosystems and environments.

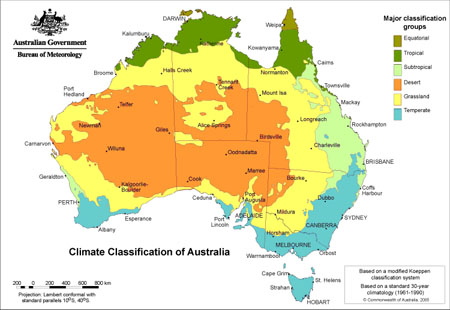

The impacts mentioned above highlight the importance of Indigenous participation in the development and implementation of responses to climate change, particularly, where responses will be required to address a diverse range of issues, dependent on the region and its climatic features. This includes responses that appropriately respect the link between local culture and tradition and local physical environments. For example, the needs of Indigenous peoples who rely on the river systems of the Murray-Darling Basin will require different responses and have access to different opportunities than those living in the tropical regions of Northern Australia. Map 2 below shows the diversity in climate across Australia.

There will also be native title and land rights implications including effects on our rights to:

- manage our lands and waters rich in biodiversity

- protect and secure the ownership and custodial rights to the Indigenous estate

- contribute, as major landholders, to the development of adaptation and mitigation strategies to address climate change

- ensure responses to climate change do not introduce laws and regulations that limit our ongoing use and enjoyment of country.

While there will be devastating impacts for some Indigenous communities that will require intensive support, other communities will be better placed to benefit from the opportunities arising from climate change. Indigenous communities will require Governments support in a number of areas in order to respond to the impacts of climate change. For instance technical and economic support will be required to ensure that the necessary governance structures are in place and infrastructure is available to communities to respond appropriately. Governments will need to give serious consideration to the provision of resources to ensure that this support is available to those Indigenous communities that require it.

As identified by the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII), Governments must work together at all levels with the full participation of Indigenous people on a ‘holistic’ response to climate change that takes account of not only the ecological dimensions of climate change, but also the social impacts and principles of human rights, equity and environmental justice.

2 The Indigenous Estate – ‘our’ greatest asset?

Text Box 1: The Indigenous Estate

In February 2005, Senator Amanda Vanstone referred to Indigenous peoples in Australia as being ‘land rich and dirt poor’.[8]

While Indigenous people have varying degrees of access and control of up to 20 percent of the Australian continent, much of which is rich in natural resources, we are also the most disadvantaged group in Australia by all social indicators.

At 30 June 2006, the Indigenous estimated resident population of Australia was 517,200 or 2.5 percent of the total population, with the majority of Indigenous people living in major cities, or regional Australia. While twenty-five percent of the Indigenous population live in remote Australia, the majority of the Indigenous land estate, located in remote areas, is managed by 1200 discrete Indigenous communities.[9] Up to 80 percent of adults living in these discrete communities rely on there natural environment for their livelihoods, including through fishing and hunting for foods, but also the use of natural resources and the environment for commercial activity such as arts and crafts, and tourism.

Many of our Indigenous communities are comparative to third world countries. However we are not afforded third world status and therefore do not have access to international programs such as those climate change programs facilitated by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), specifically developed for building sustainable Indigenous communities in third world countries.

Indigenous Australians have access to varying levels of ownership, control, use and access, or management of approximately 20 percent of the Australian continent. The Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, in her Mabo Lecture, reiterated the frustration that we as Indigenous peoples feel about our limited ability to use this significant asset to meaningfully leverage economic, social, and cultural outcomes.[10]

Australia has an extremely high biodiversity value. The Indigenous land estate in Australia includes bioregions that are of global conservation significance, with many species found only on our continent and in our marine areas.[11]

In the context of both national and international interests in the conservation and sustainable management of biodiversity, Indigenous peoples as custodians have a responsibility to ensure the integrity and maintenance of ecosystems on our lands and waters. The Indigenous knowledge around these ecosystems which have high biodiversity value will be integral to the development of adaptation and mitigation climate change strategies.

In the face of the many significant impacts of climate change, more can and should be done to collaborate and include appropriate opportunity for Indigenous Knowledge contribution in the design of solutions, not to mention the ongoing management and preservation of biodiverse and ecologically significant areas. Emerging law and policy should not restrict traditional practices or activities in these areas (including National Parks and World Heritage areas). Instead, law and policy should promote these activities and practices along with Indigenous knowledge and understandings where it is culturally appropriate or allowable.

The importance of protecting the Indigenous estate represents a significant challenge for government in developing responses to climate change. Indigenous landholders are severely under resourced and have limited capacity and infrastructure to respond to the challenges they face as a result of human induced climate change.

There is a desperate need for substantial public investment in the capacity of Indigenous people to manage this vast estate. Additionally, there is a considerable need for the Australian Government to commit to the development of a comprehensive policy for Indigenous land and sea management which co-ordinates tenure and other issues concerning the Indigenous estate.

The government has started to consider the implications for Indigenous lands and waters, identifying areas included in the National Reserve System, such as Indigenous Protected Areas (IPA’s), as a potential opportunity for economic development arising from the developing carbon markets.

However, the Indigenous estate is governed by a number of legislative and policy arrangements that will determine the extent to which Indigenous peoples engagement in the climate change debate, and the rights derived from it, can be achieved. These legislative arrangements include:

- the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth)

- various State and Territory land rights regimes

- the National Reserve System

- Cultural Heritage legislation

- a range of other laws and polices that affect lands, waters and resources including, legislation and policy associated with Australia’s Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (see below for further discussion).

I have consistently argued that some of these mechanisms have seriously limited Indigenous involvement in development opportunities. However, if Government are serious about Indigenous peoples leveraging economic benefits from the Indigenous estate, they must fully acknowledge that traditional practices, and caring for country can be of particular value in the new world of responding to climate change. It is only once this is realised that there will be scope for the protection and advancement of Indigenous interests.

As a first step in identifying climate change opportunities and issues that may arise on the Indigenous estate, State Governments will need to work with Indigenous groups to resolve outstanding tenure issues.

The States can facilitate this process by providing a full inventory that maps the various tenures (ie. Aboriginal freehold, national parks etc), where native title rights and interests have been determined, the capacity for engagement in carbon markets, and identifies lands where tenure resolution is required. This information will need to be available to Indigenous peoples and their governing organisations such as Prescribed Bodies Corporate and Indigenous Land Trusts.

2.1 Native Title

The Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (Native Title Act), provides a degree of protection for native title rights and interests held by Indigenous peoples:

Native title rights and interests in land can be an important foundation for Indigenous economic and social development. Economic returns can flow from Indigenous people developing the land and the resources contained on the land, from companies seeking access to the land and resources for development purposes, and from the cultural assets of the group and their unique relationship to the land.[12]

The ability of Indigenous people to take the greatest advantage of the native title system for our economic and commercial benefit - to leverage the system - is contingent on many factors that are often outside our control.

The extent of recognition and protection, as confirmed by the High Court in Western Australia v Ward[13], is restricted by the ability for native title applicants to prove a continued system of traditional law and custom, and in considering extinguishment, an examination of the intention of any conflicting legislation or any inconsistency in the nature of legal interests conferred by statute.[14]

The potential for native title to achieve real outcomes for Indigenous people is also limited by a general lack of recognition of commercial rights. Native title is subject to various caveats in terms of how rights and interests can be exercised on the lands and waters and whether native title rights and interests will be protected from new development and activities by negotiations with governments and other stakeholders.

As many people are aware, the resolution of native title claims can take years. This puts serious limitations on the enterprise options for the land. In many instances, native title rights and interests have been granted for non-commercial use only. This has significantly restricted Indigenous people’s ability to leverage native title rights to achieve economic outcomes.

In the context of climate change and the potential to leverage economic development opportunities from carbon markets, clarification is required as to the legal recognition of carbon rights in trees on Indigenous lands. As noted by Gerrard:

The nature of these carbon rights varies across jurisdictions. There is inconsistency in relation to the land on which these carbon rights may be created, whether these carbon rights create an interest in land, and whether harvesting rights are separate from sequestration rights. As a result, the interaction between carbon rights in trees and other legal interests, including native title is complex. New laws, regulations and markets present the possibility of a further decrease of Indigenous peoples’ rights and interests through extinguishment or suspension of native title and restricting rights in relation to access and use of natural and biological resources.[15]

In order to maximise the benefits and opportunities available to Indigenous people from climate change, Government agencies with responsibility for native title will need to give serious consideration to the current operation of the native title system. This will include an assessment of the legislative arrangements.

(a) Agreement Making

Native title agreement making, through Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs), provides an opportunity for native title holders to bring to the negotiation table their agenda for economic and social development. These agreements may also include issues about use and development on their lands, economic and employment outcomes and other outcomes such as the protection of cultural heritage.

Through this process governments come to understand and respond to the social and cultural context for the development objectives of the group. Native title agreements can then be tailored to the development needs of the claimant group.[16]

For example, template ILUAs such as the Central Queensland Agreement template[17], may provide a framework for future agreements and engagement around environmental and carbon markets. Agreements such as these may be a useful tool where industry and governments will be considering carbon offset options on Indigenous lands, in providing non-native title outcomes.

The outcomes of agreements are in large part determined by the attitude of governments and other parties to the negotiations. In some areas, governments continue to present significant barriers to the realisation of indigenous peoples’ advancement, particularly through the oppositional approach that is taken to the recognition of Indigenous peoples’ rights to land through the formal native title system. While States and Territories have started to engage more proactively in their legislative and policy endeavours to improve the current system, there is still room for improvement.

As I have outlined in previous Native Title Reports, in order to achieve successful and sustainable agreements, the process and framework for the negotiation is crucial. For example:

- the necessary resources required to ensure the full and effective participation of native title holders must be made available

- Indigenous decision-making processes must be incorporated into the agreement-making process including whether the agreement is private or available for public access and what benefits are derived from the agreement

- native title holders must have access to information they require to make informed decisions

- a process for short-term and long-term implementation which clearly outlines the roles and responsibilities (including a commitment of resources) of each of the parties must be included in the agreement.

(b) The capacity of the native title system to deliver

The Attorney General has announced his desire to encourage all governments at the Native Title Ministers Meeting in July, to work together through ‘co-operative federalism’ to find a new approach to resolving native title and land and water issues.

As is widely recognised, Native Title Representative Bodies and Prescribed Bodies Corporate are severely under-resourced. Increased financial and training support will be required to ensure the effectiveness of the native title system. Effectiveness does not simply refer to the ability to settle outstanding claims but also in the sense of supporting native title holders beyond settlement to implement and grow opportunities.

Resources are needed, firstly, to meet the priorities of Indigenous peoples on native title lands to maintain and conserve the biodiversity of their country. And secondly, to build capacity for Native Title Representative Bodies, Land Councils, Indigenous community organisations (eg. PBCs and Land Trusts) and Indigenous businesses to develop economic opportunities (such as carbon credit generation and trade), that meet the needs of their communities.[18]

As discussed by the previous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner:

...Native title agreements provide an opportunity for the parties to develop a framework to enable the traditional owner group to build the capacities and the institutions necessary to achieve their development goals.[19]

He argued that implementing capacity development through native title agreements requires a significant change of approach to native title agreement making, not just by government but also by traditional owner groups and their representatives. Framework agreements should acknowledge that capacity development is:

- a long-term process requiring the investment of consistent and adequate resources. (The benefit of a financial commitment in capacity development is a community which is ultimately self-supporting and self-governing)

- an ongoing process during which communities can learn from their experiences and build on their changing abilities

- a staged process, determined by the growing capacity and skill base of the group.[20]

Government departments should consider native title when developing Indigenous focused policies and projects. The native title system and land rights regimes should complement, and be complemented by other relevant areas of policy and legislation to ensure native title rights and interests are fully effective.

A major issue in trying to use native title land as a basis for enterprise is the possible suspension and effective regulation of rights and interests through the future acts regime. This means that even if claimants are successful in a native title claim, their rights and interests can be easily and lawfully impacted upon by activities conducted in accordance with the future act process.

This highlights the need to ensure the inclusion of native title and land rights considerations in the formulation of climate change policy and legislation as a matter of urgency. If clearly foreseeable issues are addressed up front, at the developmental stages, the risk of undermining aspects of climate change policy, emissions trading regulation and other responses where Indigenous engagement will be crucial, may be minimised down the track. Addressing issues in the formation stages also reduces the risk of inadvertently creating unfavourable legal and policy precedents.

Native title has been considered a hurdle to achieving economic development. However, with the Australian Government encouraging a more flexible approach towards native title[21], there is the potential for Indigenous people and governments to develop a climate change policy that achieves real outcomes and provides better protection of (exclusive and non-exclusive) native title rights and interests for Indigenous people and their communities.

Further, in addition to the base level legal requirements under existing legislation, best practice principles of engagement with Indigenous peoples and their communities should be developed to guide information and technology sharing and access to the Indigenous estate for climate change related projects and initiatives. Further discussion of best practice principles is returned to shortly.

2.2 Land Rights

The long struggle for land rights in Australia has meant that Indigenous people now have a degree of ownership, control or management of approximately 20 percent of Australian lands and waters. However, not only are land rights and native title different legal regimes and different in their respective implementation, they can interfere with Indigenous rights and interests in their interaction with one another’s areas of policy. In addition, most States and Territories have also developed alternative land regimes, which in some cases are inconsistent with national approaches. For example, those Indigenous groups in more remote regions, such as those in Cape York, Queensland who have had Aboriginal freehold lands returned to them under state land rights regimes may be in a better position to achieve their cultural, social, and economic aspirations than even those who have been successful in a native title process.

As a general principle, of all lands either owned or controlled by Indigenous peoples across Australia, those Indigenous communities who have had inalienable or alienable freehold lands returned to them under the various land rights regimes are best placed to engage in economic ventures linked to carbon and environmental markets. However, the full realisation of potential carbon sequestration (storage or absorption of carbon dioxide in trees, plants, wetlands and soil etc), will depend to some extent on the strength of the Governments commitment to recognise the right of, and to provide economic opportunities for Indigenous people in the carbon market.

For example, land handed back to Aboriginal people under land rights regimes that are National Park lands, has not yet been identified by the Government as an option for carbon offsets. For Indigenous peoples, particularly on those national parks where joint management is in place, this could provide an opportunity for Indigenous people who own or jointly manage country to be recognised for our previous, current and future contributions to conservation on our lands. It may also provide the basis for an additional income stream all stakeholders involved.

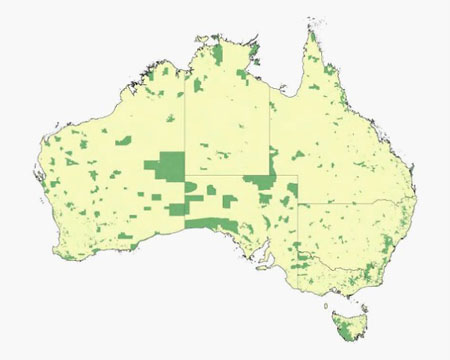

2.3 The National Reserve System

The National Reserve System is a nation-wide network of approximately 9000 protected areas, which currently covers more than 88 million hectares (11 percent) of the country. Aimed at conserving Australia’s unique landscapes, plants and animals, these areas include:

- National Parks

- Conservation areas on private lands

- Indigenous Protected Areas

- Other reserves.[22]

Map 1: Australian National Reserve System accounts for 11.5% of Australia’s land area (88,436,811 ha) and has 8667 protected areas[23]

Text Box 2: The National Reserve System has its origins in the Rio Earth Summit of 1992.

Australia played an active role in developing the Convention on Biological Diversity - the groundbreaking international treaty which links sustainable economic development with the preservation of ecosystems, species and genetic resources. When the Rio Earth summit adopted the Convention in 1992 Australia was one of the first of 167 nations to sign and to ratify.

On signing the Convention, Australia agreed to establish a National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia's Biodiversity and a system of protected areas.

To carry out its promise, the Australian Government began working with the states and territories, who have constitutional responsibility for land management. In a historic step forward, all governments agreed to build a network of land and marine protected areas.

The resulting land-based network of protected areas is called the National Reserve System. A separate program exists for marine protected areas.

By 1996, the National Reserve System consisted of more than 5,600 properties covering almost 60 million hectares.

Recognising that some of Australia's most valuable and rare environments are on land owned by Indigenous communities, the Australian Government also began working on an exciting new concept which would later become Indigenous Protected Areas.[24]

The Government has identified Australia’s Indigenous Protected Areas[25] (IPAs) and other Indigenous owned or managed lands and waters as a potential biodiversity conservation and carbon sequestration investment opportunity. Sixteen percent of Australia is identified as important ‘biodiversity hotspots’ for carbon sequestration and biodiversity protection, with an increasing economic value in environmental and carbon related markets.[26]

Indigenous peoples are actively engaged in providing environmental management services in coastal management and security, weed management, and feral animal control. Existing programs such as the Caring for Country Initiative, the Working on Country Program[27], and new national park joint management arrangements in Cape York[28], which aim to build on Indigenous knowledge of protecting and managing land and sea country provides funding for Indigenous people to be trained and employed as Rangers to deliver environmental outcomes. There is significant scope to build and develop these programs further through emerging climate change responses, such as emissions offsetting and carbon trading.[29]

Activities such as fire and feral animal management regimes, as well as potential for carbon sequestration and offset arrangements may be possible for Indigenous people on their lands under the National Reserve System. However, the ability for Indigenous people to access such opportunities is dependent on Government ensuring that, in developing climate change policy, National Reserve lands (particularly those that are Indigenous owned or co-managed, ie. National Parks) are open to these activities and are included in the National Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme. The Message Stick Carbon Group stressed that:

Clarity should be provided around the governments stand on avoided deforestation being discussed in the context of the developing countries for the post-Kyoto mechanism. This must also include forested lands owned by Indigenous Australians locked away at present from economic activity in the form of State Forests, National Parks etc.[30]

The Government has committed to increase funding to a total of $50 million over five years to improve and expand the Indigenous Protected Areas Program within the national reserve system. As discussed above, these lands have been identified as integral to the development of climate change responses, and opportunities for economic outcomes for Indigenous communities. While $50 million is a positive start, it will not be sufficient to meet the needs of Indigenous peoples nationally to design, develop and implement long-term sustainable projects.

For example, the West Arnhem Land Fire Abatement project took up to ten years to develop.[31] If Indigenous involvement in emissions’ trading is genuinely intended by governments, then greater assistance will be needed to ensure projects meet the standards prescribed by emissions trading schemes.[32] These standards involve intensive verification and registration processes, as well as ongoing reporting obligations. Funding and other resources must enable Indigenous people to meet these and other preliminary market access requirements if meaningful involvement in emerging markets is going to be realised.

2.4 Cultural Heritage

Everything about Aboriginal society is inextricably interwoven with, and connected to the land. None of it is vacant or empty, it is all interconnected. You have to understand this and our place in that land and the places on that land. Culture is the land, the land and spirituality of Aboriginal people, our cultural beliefs and our reason for existence is the land.[33]

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) anticipates that changes to land cover and biodiversity caused by climate change, could force Indigenous people to ‘alter their traditional ecosystem management systems’ and, in the extreme, ‘eventually lead to a loss of their traditional habitats and along with it their cultural heritage’.[34]

Significant work is required to effectively engage Indigenous people in climate change law and policy in Australia. Through the introduction of legislation such as the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), and Cultural Heritage legislation, the Australian Government is achieving a degree of recognition and respect for the unique rights that Indigenous peoples have to our lands. However, these laws provide limited recognition and are not sufficient or effective.

The importance of culture and its relevance to Indigenous people’s relationship to our lands [and waters] is something that government and non-Indigenous people have a hard time understanding. This is evidenced by the fact that governments continue to develop Indigenous land policy in isolation to other social and economic areas of policy, including native title and cultural heritage legislation.

For example, Australia has the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984, a legislation enacted by the Commonwealth Government. The purpose of this Act is to preserve and protect places and objects of cultural significance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Currently the legislation provides this protection at the national level for all states but delegates its powers to the States and Territories.[35] Additionally, each State and Territory has their own cultural heritage legislation. I am concerned that this approach leads to inconsistent implementation, and outcomes are dependent on the incumbent state or territory government. For example, monitoring and assessment of the interplay between State and Federal regimes and its delivery of protection for Indigenous cultural heritage is necessary to ensure the outcomes are being achieved.

Additionally, there are significant differences between State and Territory heritage protection laws and there are problems in how well each of them actually protects Indigenous cultural heritage. In particular, there is a stark difference in the treatment of non-Indigenous heritage compared to Indigenous cultural heritage. This includes provisions relating to liability for damage or destruction of Indigenous cultural heritage which must also be consistent with that applied to the protection of non-Indigenous cultural heritage.[36]

While climate change may provide some opportunities for Indigenous peoples to increase their current land management responsibilities, especially in areas of high cultural heritage and biodiversity value, Indigenous cultural heritage may be threatened in other areas. The forced migration of peoples from their lands may mean fewer people remaining on country to respond to the environmental threats through active land management.

Federal policies and programs including the Indigenous Heritage Program and Indigenous Protected Areas[37]are contributing to increasing the extent of recognition and land management activity on country. The Working on Country program[38] aims to achieve the maintenance, restoration, and protection of Australia’s land, sea and heritage environment by contracting Indigenous people to provide the necessary environmental services.

Programs such as this benefit the Australian community, and at the local level, employment opportunities which allow the Indigenous custodians of the land to continue their cultural responsibilities also advance the livelihoods of Indigenous people. These programs may also provide a foundation for the recognition and participation of Indigenous peoples in carbon and environmental markets which benefit the Australian community.

2.5 Diverse Climatic Regions

The diversity of climate across the Indigenous estate will also require diverse approaches to climate change that consider not only the economic opportunities, but a full assessment of the potential impacts and responses required.

For example, the top end and much of the east coast of the country is tropical or subtropical coastal areas, while the majority of the country inland and to the west coast is grassland or desert. These areas provide the homelands of Indigenous peoples. Both regions will require different, but equally important responses to climate change. Indigenous knowledge of the macro and micro diversity in these areas is of important value in formulating solutions and responses to climate change. As stressed by Gerrard:

Indigenous peoples have a ‘special interest’ in climate change issues, not only because through their physical and spiritual relationships with land, water and associated ecosystems, they are particularly vulnerable to climate change; but also because they have a specialised ecological and traditional knowledge relevant to finding the ‘best fit’ solutions.[39]

Appendix 6 provides a summary of the projected climatic impacts on various regions, and the potential impacts on Indigenous communities.

Map 2: Australian climate zones – major classification groups[40]

3 The climate change challenge

A number of challenges arising from climate change are critical to the lives of Indigenous people. These challenges will require specific strategies to reduce the impacts on Indigenous people. These challenges, if given serious consideration, can be addressed. However, in order to turn these challenges into opportunities there first needs to be understanding and recognition of the extent of the possible threats. Some of the challenges presented by climate change include:

- access to information

- pressures on Indigenous lands and waters - environmentally, culturally, socially and economically

- health and well-being of Indigenous people – psychologically, physically

- protection of Indigenous knowledges

- effects of current and future responses to climate change (policy and regulation) on existing legal rights and interests.

3.1 Access to information

With regard to the various reports published on climate change impacts and responses, much of the scientific and economic modelling has been developed by technicians with specific expertise in the area. This is due to the complexity of climate change.

The most important issue for Indigenous people to adequately address the challenges arising from climate change is the need to understand what climate change is and:

- how it will affect our access and rights to our lands and waters

- how it will impact our environment

- what is carbon and what are the threats and opportunities for us arising from this new thing everyone is talking about.

We must be fully engaged as equal stakeholders. We must also be fully apprised of the benefits and the costs resulting from legislative and policy developments, or negotiated agreements. This requires adequate and appropriate consultation and access to information and advice that is understandable and accessible for communities and affected peoples.

There is currently no mechanism or communication strategy for this to occur. This is a critical oversight and a major concern for Indigenous peoples.

In my Native Title Report 2006[41], I presented the results of a national survey I conducted on land, sea and economic development. The survey results demonstrated that the majority of traditional owners did not have a sufficient understanding of land agreements. This raises questions about our capacity to effectively participate in negotiations and consequently may limit our ability to leverage opportunities from our lands.

The survey also highlighted the need for an information campaign to improve understanding of land regimes and the funding and support programs available to assist indigenous people in pursuing economic and commercial initiatives. Information is power and information is crucial for Indigenous participation in emerging carbon markets and to ensure that decisions made by Indigenous land holders are made with their free, prior, and informed consent. A lack of information will limit our capacity to effectively participate in this important area of policy and opportunity.

An urgent information campaign is required that includes information about:

- Commonwealth and State policies related to climate change and how Indigenous peoples’ rights and other fundamental human rights will be affected by those policies

- how climate change policies will interact with and be relevant to native title, land rights, and cultural heritage legislation

- how climate change policies will interact with and be relevant to lands included under the National Reserve System

- how climate change policy will interact with and be relevant to the Indigenous Economic Development Strategy

- what funding and support programs will be available to facilitate Indigenous participation in climate change policy development and opportunities

- what other support (corporate and/or philanthropic) is available.

The importance and urgency of this fundamental step cannot be over emphasised.

In order to ensure that policies are appropriately targeted to achieve the desired outcomes, the Government will require reliable information about traditional owner priorities for land. In the same way, traditional owners require information about the Government’s policies before they can make informed decisions about land and future social, cultural, and economic opportunities relevant to climate change. This will mean the full participation of and effective consultation with Indigenous people on this subject.

3.2 Pressures on Indigenous lands and waters

(a) Interaction between legislation and policy areas

In order to adequately address the impacts of climate change and maximise the opportunities available to Indigenous peoples in Australia, governments will be required to work together to ensure that policy and legislative arrangements are conducive to achieving real outcomes.

A major barrier to successful outcomes for Indigenous peoples has been the inconsistency of approach between federal and state government policy and the lack of cooperation and compatibility between legislative arrangements.

The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’ affirms the right of Indigenous people to participate in decision-making in matters that affect their rights. Governments are also urged to consult and cooperate in good faith with Indigenous people to obtain our free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that affect us.[42]

As a minimum, it will be fundamental for Federal Government Departments including the Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, the Department of Climate Change, the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, the Attorney General’s Department and others including the Department of Health, to work together with the full engagement and participation of Indigenous people in the development of policies both domestically and internationally, concerning climate change from the outset.

The Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs and the Attorney General’s Department have a significant role to play in facilitating a consistent, innovative approach to Indigenous participation in climate change policy. This is will be particularly important in areas where, for example, tenure reform will be required to achieve key opportunities from carbon markets on Indigenous lands.

(b) International and domestic offset investment from transnational corporations and governments

Australia is at an environmental advantage in our ability to leverage carbon offset opportunities from our extensive forest and natural vegetation cover. It would be in Australia's interest to be able to offset emissions from the stationary energy sector with offsets in the agriculture and forestry land use sectors. While issues of measurement are significant, there is a window of opportunity in the early stages of an Emissions Trading Scheme to allow offsets.[43]

To not have forestry offsets is to miss the opportunity for massive abatement, while also missing the opportunity for economic opportunities in remote and regional Australia for Indigenous Australians. This would be a sizable missed opportunity.[44]

As discussed in the previous chapter, Australia has responsibilities under the Kyoto Protocol. As a party to the Protocol, the Australian Government are currently developing the national emissions trading scheme, the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme[45], which regulates the generation and trade of carbon credits.

The Kyoto Protocol includes mechanisms to assist countries to meet their targets and responsibilities. These mechanisms are called ‘flexibility mechanisms’ and they enable parties to the Kyoto Protocol to generate and trade permits or ‘credits’ on emissions trading markets. The flexibility mechanisms are:

- Emissions trading – known as ‘the carbon market’

- The clean development mechanism (“CDM”)

- Joint implementation (JI)[46]

The CDM involves investment in sustainable development projects that reduce emissions in developing countries, while the joint implementation mechanism (JI) enables industrialised countries to carry out emissions reduction or sequestration projects with other developed countries that have ratified the Kyoto Protocol.[47]

It is unfortunate that Australia’s proposed Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, does not include a domestic mechanism similar to the CDM. A similar domestic initiative could promote technology and knowledge transfer, with and end goal of sustainability (emissions reduction) and could provide incentives for projects in less developed or low-economic communities, including remote Indigenous communities.

The joint implementation strategy will only be available for developed countries to enter agreements between other developed countries.[48] As developing countries have not yet been allocated reduction targets under the Kyoto Protocol this mechanism will not be available to developing countries.

Allowing for JI projects in Australia under the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme will open opportunities for foreign companies/persons to generate ‘carbon credits’ to be used or traded under the Kyoto Protocol.

Projects initiated under the JI mechanism will have implications for Indigenous peoples in Australia and in other developed nations. This is particularly in relation to the participation of Indigenous peoples in negotiations under this mechanism. The JI mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol provides that projects are only required to have the approval of the host Party, and participants have to be authorised to participate by a Party involved in the project.[49] In Australia, this would mean that the Federal Government authorises agreements for offset investment opportunities.

As I reported in my Native Title Report 2007, traditional owners in western Arnhem Land entered a voluntary agreement with a liquefied gas company in Darwin to offset the company’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Australia is already open to projects or project investment through offsets for voluntary markets.

However, current legislative arrangements in Australia, including native title, land rights, and cultural heritage, are unlikely to provide adequate protection or provision for Indigenous rights and interests in Kyoto projects or in domestic carbon trading arrangements. In the native title context, projects proposed on native title lands and waters will be considered in light of the future act regime and many projects are unlikely to attract the right to negotiate. Without more direct access points to emerging markets, inadequate mechanisms to bring all parties to the table further undermine our ability to negotiate full and equitable access to new economic opportunities.

Text Box 3: Western Arnhem Land Fire Abatement (WALFA)

The WALFA project mitigates wildfire by reintroducing traditional Indigenous fire management regimes, resulting in reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

The project aims to generate opportunities for Indigenous communities to engage in culture based economies and provides economic, cultural, social, and environmental benefits for Indigenous people and the wider Australian community, and creates an offset for the industry partner. Due to the voluntary nature of this agreement, it did not require the approval of the host party, the Government.[50]

While carbon offset agreements have been negotiated with Indigenous groups in Australia, there is an urgent need for clear principles of best practice and rules to be developed around future negotiations.

The Australian Government has committed to facilitating participation of Indigenous people in carbon markets. [51] A legal framework is needed to create certainty and clarity around this participation. Such a framework should include national principles that provide for:

- the full participation and engagement of Indigenous peoples in negotiations and agreements between parties

- the adoption of and compliance with the principle of free, prior and informed consent

- the protection of Indigenous interests, specifically access to our lands, waters and natural resources and ecological knowledge

- the protection of Indigenous areas of significance, biodiversity, and cultural heritage

- the protection of Indigenous knowledge relevant to climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies

- access and benefit-sharing through partnerships between the private sector and Indigenous communities

- non-discrimination and substantive equality

- access to information and support for localised engagement and consultation.

In addition, greater involvement of Indigenous peoples in Australia’s international negotiations for the “second commitment period” of the Kyoto Protocol, post-2012 is essential and urgent. Particularly in relation to the development of culturally inclusive rules around the operation of a national emissions trading scheme and the potential for international investment.

(c) Dispossession and Migration

Climate change will inevitably result in the migration and dispossession of Indigenous peoples who are displaced from their traditional lands and territories due to coastal and land erosion and rising sea levels. Indigenous island communities and those located along the coastline of Australia will be significantly affected with some people having no other choice than to move to higher lands on their islands, to other islands, or to the mainland. With a history of dispossession of Australia’s Indigenous peoples, extensive engagement is needed to ensure that the mistakes of the past are not repeated, and that any cultural tensions that may arise as a result of relocations are minimised or avoided.

The Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that the Torres Strait Islands are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. [52] In discussions with a number of Torres Strait Islander people, the impacts are already being felt, with unprecedented flooding from surging king tides and the increasing intensity of extreme weather events[53]:

Over the past two years, half the populated islands of the Torres Strait have experienced unprecedented flooding from surging king tides. According to the draft of the fourth Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report,...the king tides have exposed a need for better coastal protection and long-term planning to potentially relocate half the 4000 people living on the islands.[54]

Case Study 1 in this report provides further discussion on the impacts of climate change in the Torres Strait region.

Indigenous people located in the remote interior will also be affected, particularly by deforestation, restricted access to natural food sources and other resources, and the degradation of lands and waters. This is becoming increasingly evident in the Murray-Darling region where non-Indigenous people are relocating from their farmlands and desert regions into urban centres. This has left Indigenous people to bear the brunt of the impacts of climate change, while also facing risks of involuntary relocation.

The development of well-intentioned mitigation strategies may also result in the dispossession of Indigenous peoples from our lands, through the loss of access to traditional lands, waters, and natural resources. In particular, where Indigenous lands will be in demand by transnational corporations for land to produce biofuels, and to plant monocultures for carbon trading offsets.[55]

The lack of access to traditional lands, waters and natural resources could diminish our ability to care for country and to maintain culture. Indigenous peoples will no longer be in a position to undertake responsibilities to land and water management, which will result in environmental degradation, and impacts on overall health and well-being. This is not only a concern for Indigenous peoples. This will affect also Australia’s biodiversity and ecosystem maintenance.

Additionally, Indigenous peoples from our neighbouring Pacific Islands may also be forced to migrate to Australia as a result of climate change, particularly in the event of sudden climatic events. Again, there are lesson’s to be learnt from the past in terms of relocating people and communities and the need to engage extensively to ensure that the impact on both the relocated and the host community is as minimal as possible. The Fourth Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns that:

About 60, 000 to 90, 000 people from the Pacific Islands may be exposed to flooding from sea-level rise each year by the 2050’s.[56]

Further, the United Nations University estimates that by 2050 up to 200 million people globally will be displaced by environmental problems. They argue that the issue of migration represents the most profound expression of the inter-linkage between the environment and human security.[57]

The future security of the Australian coastline will pose a significant challenge to governments and to the Indigenous peoples as many communities are located along the northern and western Australian coastline.

This will not only place extra pressure on Indigenous lands in Australia, and potentially dispossess those Indigenous peoples from their lands, but accommodating climate refugees will have a significant impact on the Australian economy.

(d) Deforestation and monocropping – deforestation vs reforestation

In Australia, industrial-plantation forestry has increased by 6,000km2 in the past decade.[58] As a proportion of the total area of agricultural land, this may be regarded as a small change. However, in south-western regions of Victoria and the Riverina in the Murray-Darling Basin, new plantation forestry represents a significant change in land management. Problems that arise from this change in land use and land management includes:

- significant native vegetation removal and concomitant native animal removal

- monocrops are feral animal havens

- many of these crops experience herbicide application

- young tree growth in areas where they are not grown naturally has significance adverse affects on water supplies and ground water levels.[59]

I am concerned about the impacts of current and historic land clearance and deforestation on Indigenous lands which has and will make way for the creation of large scale plantations in order to benefit from the carbon trading industry. In particular, opportunities under the new Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, mainly for people who created the problem by clearing our lands in the first place. The World Rainforest Movement is particularly concerned about these negative social and environmental impacts:

When natural ecosystems are substituted by large-scale tree plantations they usually result in negative environmental and social impacts: decrease in water production, modifications in the structure and composition of soils, alteration in the abundance and richness of flora and fauna, encroachment on indigenous peoples' forests, eviction of peasants and indigenous peoples from their lands, loss of livelihoods.[60]

The Australian Government are of the opinion that the inclusion of forestry on an opt-in basis will provide an incentive for forest landholders, including indigenous land managers, to establish additional forests, or carbon sinks (forests planted for the purpose of permanently storing carbon). In particular, they argue that the incentive will be greatest for carbon sinks that are planted with no intention of cutting the trees down.[61]

While some indigenous people will be able to access economic opportunities from commercial tree plantations, others will not and may not see this option as appropriate. [Even where it is considered appropriate, the proposal for only landowners, long-term leaseholders and carbon rights holders to participate in the scheme has the potential to further limit Indigenous involvement. In many cases the consent of a Minister is needed to grant leases or create third party interests in Indigenous land. I believe these issues have not been sufficiently evaluated in terms of their potential to restrict Indigenous participation in emerging opportunities.]

For example, up to 75 percent of south eastern Australia has been cleared with only a few remnant River Redgum and other forests remaining.

Further north, the Indigenous lands of Melville and Bathurst Islands in northern Australia, have been devastated by the clearing and destruction of eucalypt forests. A Perth-based company, Great Southern Limited, has reportedly destroyed large tracts of native eucalypt forest which is being chained and burned and replaced with monoculture plantations to be wood chipped and exported to Asia.[62] Upon investigation, the Federal Government recently found Great Southern Limited breached environmental conditions by clearing into a buffer zone that protects rainforests and wetlands. This project was approved under the condition that there would be no clearing within buffer zones designed to protect important rainforest and wetland habitats. The Company have been ordered to pay up to $3 million to conduct remediation work.[63]

As stressed by the Australian Indigenous Peoples Organisation (IPO) Network:

New laws and policies addressing climate change and other environmental issues such as deforestation are being progressively introduced, which have the potential to erode Indigenous rights and interests. This is done both directly by overriding rights through legislation, or indirectly by promoting and prioritising commercial and non-Indigenous interests with little space and support for Indigenous peoples to meaningfully engage and access new opportunities.[64]

Deforestation and changes in land use contribute significantly to global climate change due to the release of carbon dioxide when forests and forest products are burned. If the forest is converted to other uses such as agriculture, future carbon sequestration is also lost.[65]

For every 25,000 hectares cleared, at least 4.7 million tonnes of greenhouse gas will be produced. The short rotation plantations will never have the capacity to absorb enough carbon to abate the emissions.[66]

Additionally, Indigenous peoples’ right to development is denied where deforestation and land clearing has provided a lucrative industry. As with many other examples Indigenous peoples are not employed or engaged in the timber or logging industry in any significant or meaningful way.[67]

However, Indigenous lands offer mature established native forests (natural carbon sinks) that have a significant capacity for carbon abatement, and would benefit from carbon certificates in recognition of this, rather than being forced into plantations.

Natural carbon sinks are a key feature and economic option on Indigenous lands. The challenge for the Australian Government will be in providing leadership in its climate change policies and international negotiations to include native forests and national parks as options for Indigenous sustainable development and carbon sequestration in Australia.

While international programs such as the Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD) exclude native forests as carbon sinks, the Voluntary Carbon Standard has released guidelines for avoided deforestation projects which accredit carbon credits through REDD.[68] Parties to the Kyoto Protocol also resolved to further consider ways in which benefits for avoiding deforestation can be included in current and future mechanisms at the UNFCCC COP13 in Bali as part of the Bali ‘road map. The Conference of the Parties noted:

the further consideration, under decision 1/CP.13, of policy approaches and positive incentives on issues relating to reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries; and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries.[69]

A key issue in relation to avoided deforestation is the distribution of benefits. In developing countries Indigenous groups have raised concerns that REDD will mean that governments and industry get paid to stop activities that they should not have been conducting in the first place, such as extensive land clearing. They are particularly concerned that communities on the ground will not see any of the economic benefits derived from activities conducted on their lands, and that they will potentially be locked out of areas used for REDD projects.[70]

The issues discussed above will be a significant barrier to sustainable development for Indigenous populations in developing countries, However developed countries with Indigenous populations, such as Australia should consider the impacts and opportunities arising from programs that relate directly to developing countries to ensure that policies regarding climate change and in particular land clearing and deforestation do not continue to disadvantage Indigenous peoples.

(e) Conservation and Heritage Listing

Conservationists and environmental groups have been working with and lobbying governments to increase the conservation on land with high biodiversity, particularly in light of the threats posed to Australia’s biodiversity from the impacts of climate change.

Indigenous people are fully supportive of land and biodiversity conservation and this is evidenced by the constant efforts of Indigenous people to engage in land management and caring for country initiatives. However, what was a positive working relationship between the conservation and environmental groups has become disjointed due to the pressure on Indigenous peoples to develop sustainable communities by maximising the economic opportunities available to them on their lands and waters. From an Indigenous perspective, conservation and economic development are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

I am concerned however, that negotiations with governments are occurring without the participation of Indigenous people, and legislation is being developed and implemented without consultation or the consent of Indigenous communities. The Wild Rivers Act 2005 (QLD) is an example of where this has occurred. While this legislation gives the rivers protected status, Indigenous peoples are concerned that it also has the potential to limit rights to use the waterways for traditional activities such as hunting, and future economic development.[71]

Indigenous lands are also high on the conservation agenda for World Heritage Listing. Indigenous peoples have voiced their concerns that their lands are being ‘locked up’. [72] While some Indigenous peoples have advised that they support the need to protect their lands from high impact development, such as the Burrup Peninsula, the nomination and declaration of lands for World Heritage Listing must happen only with the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous landholders.

These arrangements must also protect the rights of Indigenous people to development, and not restrict or exclude them from pursuing their aspirations on their lands.

Indigenous peoples have a right to development, including a right to the conservation and protection of our environment and the productive capacity of our lands and resources. We also have the right to utilise our lands, waters and resources in order to fulfil those rights. Additionally, Indigenous peoples have the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for exercising our right to development.[74]

3.3 Health and well-being of Indigenous people

Climate change is a significant and emerging threat to human health. However this threat is even more prevalent for vulnerable populations including Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous peoples in Australia do not enjoy the same opportunities to be as healthy as the non-Indigenous population particularly in relation to access to primary health care, medicines and health infrastructure. Achieving the right to health in Indigenous communities will be made harder as a result of climate change.

The right to health[75], obliges a state to ensure that everyone – regardless of race – has an equal opportunity to be healthy.

Fulfilling a right to health mean that communities across Australia (whether Indigenous or non-Indigenous) should enjoy a similarly healthy standard of drinking water, be able to access roughly the same standard of fresh vegetables, fruits and meat, and have their sewerage and garbage removed. It also means that they should be able to enjoy, from a health perspective, the same standard of housing that is in good repair with functioning sanitation and is not overcrowded.

Recent developments in Indigenous health are aimed at reducing the current disparities between the health of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. As a result of a two year campaign led by my Office, in March 2008, the Prime Minister and every major indigenous and non-indigenous organisation from the health, human rights, reconciliation and NGO sectors committed to a new relationship with the express purpose of eliminating the 17 year life expectancy gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians by the year 2030. These bodies also committed to halving Indigenous infant mortality rates within 10 years, consistent with the Millennium Development Goals. Those in the health sector must also be mindful of, and adapt strategies to accommodate, the effects of climate change on health outcomes in order to achieve these targets.

(a) General health and well-being

As discussed earlier in this chapter, the impacts of climate change on the natural environment have the potential to disturb Indigenous people’s connection to country and their land and water management responsibilities. For Indigenous peoples whose land is life, there could be a range of direct and indirect health impacts including mental and physical impacts.[76] Green suggests:

When considering the likely health impacts from climate change on Indigenous Australians living in remote communities it is crucial to explicitly address the interconnections between the health of ‘country’, culture and mental and physical well-being.

For example, environmental change could affect traditional activities including ceremonial practices, hunting and bush tucker collection – impacts that have implications for mental health as well as nutritional intake.[77] Preexisting physical and psychological diseases caused by dispossession and poverty further challenge the ability of Indigenous communities to cope with the health impacts of climate change.[78]

Recent assessments conducted on the impacts of climate change on health in Australia, highlight the potential for the onset of and increases in vector-borne, water-borne and food-borne diseases such as: malaria, dengue fever, Murray Valley encephalitis, Japanese encephalitis, melioidosis, leptospirosis and scrub typhus.[79]

(b) Food security for remote Indigenous communities

The IPO Network in their submission to the United Nations Permanent Forum voiced their concerns that changing climatic patterns will affect the viability of food and water sources which impact directly on the life and health of Indigenous people:

The dietary health of Aboriginal communities is predicted to suffer as the plants and animals that make up our traditional diets could be at risk of extinction through climate change.[80]

Access to fresh food and vegetables will be further limited by the increasing costs of transportation from major centre’s and storage where many communities run their electricity supplies off diesel run generators. Not only will the use of diesel generators continue to emit high levels of greenhouse gases but the supply of fuel is also becoming more expensive and less environmentally viable particularly for remote Indigenous communities.

Salt water inundation of fresh water supplies will also impact on the capacity of Indigenous communities to grow fresh fruit and vegetables, and access fresh drinking water. The lack of fresh water will also have considerable impacts for those communities servicing Indigenous people suffering from chronic illnesses such as diabetes and renal disease, and requiring dialysis treatment. Some of these communities have fought tirelessly to obtain these services in their regions, and while few communities are equipped with the infrastructure to provide these crucial primary health services, those that do may again be required to travel to urban centres for treatment as a result of climate change.

Urgent research and assessment is required to determine the impacts on Indigenous people’s health in remote and regional communities to ensure that residents on these communities have access to basic services including primary health care and the health services they require. Further, it is necessary to ensure that adaptive measures are preemptive rather than reactionary and that communities are in a position to respond from the outset.

In developing climate change responses to health for all Australians, governments will also need to ensure that provisions made for the assurance of health services are also available to and accessible by Indigenous peoples living in urban centres.

(c) Caring for Country

Reduced access to traditional lands can act as a determinant of health status, particularly where that land is culturally significant and provides sources of food, water and shelter.

A recent study conducted by the Menzies School of Health Research in collaboration with the traditional owners from Western and Central Arnhem Land, assessed the health outcomes of Indigenous people in relation to their involvement in natural and cultural resource management. Statistics confirm that the health outcomes in rural and remote areas of Australia are adversely affected by poor health among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who make up a greater proportion of residents in those areas.[81]

The Healthy Country: Healthy People Study[82] found that removing Indigenous peoples from their homelands had a negative effect on the health of both the tropical landscapes and those people removed, demonstrating a direct association between Indigenous ‘caring for country’ practices and a healthier, happier life.

The study also confirmed that Indigenous participation in both customary and contemporary land and sea management practices, particularly by those people living on homelands, are much healthier, with significant reductions in the rates of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

For Wattaru in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands, South Australia, the health outcomes have also improved, and this is in part credited to the Ku-ku Kan yini Project initiated in 2003. This local community has been successful in combining traditional and contemporary land management techniques resulting in increased employment outcomes and self esteem in the community, and has assisted in the control of illnesses such as diabetes.[83]

If we are serious about closing the gap for Indigenous people, particularly those living in remote communities, then we must start with what we know. That is that, employment and economic development opportunities that are built on caring for country, and caring for culture, improve the lives of Indigenous people. Issues such as these must be considered in the development of climate change policy relevant to Indigenous peoples.

3.4 Protection of Indigenous knowledge’s

Despite the existing evidence base in this area, mechanisms that protect and maintain Indigenous knowledge remain inadequate at both the international and the domestic level in Australia.

The protection of Indigenous knowledge’s will be a specific challenge for Indigenous peoples and governments around the world in their attempts to respond to the impacts of climate change. Particularly environmental responses that rely on Indigenous peoples knowledge of biodiversity and ecosystem management. As this is a significant issue for Indigenous people and climate change, this issue is further considered at chapter 7.

4 Opportunities from climate change

The realisation of the challenges discussed above can be minimised if policy is developed that considers the contributions that Indigenous people can make to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change.

To date, the Australian Government has predominantly focused on the economic potential of carbon markets through the development of an emissions trading scheme. While Indigenous people are seeking to be included in this emerging market, the opportunities for Indigenous peoples are much broader than this including:

- engagement and participation facilitated by the Indigenous Economic Development Strategy

- contributions to mitigation and adaptation measures

- The provision of environmental services

- Building sustainable Indigenous communities

- The inclusion of climate change outcomes in agreement-making

4.1 The Indigenous Economic Development Strategy

Minister Macklin in her Mabo Lecture in May 2008 announced that in order to progress the new approach to Indigenous affairs, the Australian government will be developing an Indigenous Economic Development Strategy (the Strategy).[84] If the Government are serious about building sustainable communities, the Strategy should have the potential to facilitate the engagement and full participation of Indigenous people in climate change related markets and opportunities.

Text Box 4: Indigenous Economic Development Strategy (IEDS)

The Labor Party committed to improving the lives of Indigenous Australians through economic development as part of its 2007 election campaign.[85] While this strategy has not yet been finalised, the Indigenous Economic Development Strategy must be developed to enable economic development for as many Indigenous groups as possible, and be linked to streamlining and improving Indigenous rights under legislative arrangements such as native title and land rights, cultural heritage and under various environment protection and conservation legislation, carbon sequestration and climate change, industry development regulation[86], and water legislation.

In particular, the discussion regarding the development of the IEDS draws attention to opportunities arising from water resources for local enterprise and local jobs. For example, the Australian Government has identified that in central Australia there are ‘substantial ground water resources that have not been developed outside the town areas of Alice Springs and Tennant Creek’. Working with the Centrefarm Aboriginal Corporation set up by the Central Land Council, horticulture projects are able to be established with funding from the Aboriginal Benefits Account.[87] This development must take place in partnership with the traditional owners for those lands and waters. This is to ensure that: