Native Title Report 2007: Chapter 1

Native Title Report 2007

Chapter 1

Changes to the native title system

- The native title system

- Does the native title system need changing?

- Purpose of the Native Title Act

- Native title: the state of play?

- The changes to the system

- Concerns about the changes

- Recommendations

Native title is now well established in Australian law. The native title system was set up in 1994 under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the Native Title Act). It is for gaining recognition and protection of native title, and for resolving native title matters. It has been successfully used in many parts of the country.

The system has also been used to bring together people who might not otherwise engage. It has provided Indigenous people with a ‘seat at the negotiation table’. This has lead to an increasing number of Indigenous land use agreements (ILUAs), and to contracts outside of the native title system. These cover a wide range of matters, not just native title.

It has led to registration on the Native Title Register of 68 determinations where native title exists. There have also been 280 Indigenous land use agreements registered on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements (as at 30 June 2007).

The native title system

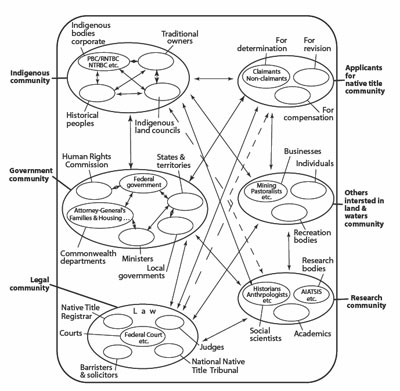

A large number of people and agencies are involved in the native title system, as shown in the simplified diagram on the next page.

Does the native title system need changing?

Despite the successes of the system, I am concerned that the native title system is not delivering substantial recognition and protection of native title. The operation of the Native Title Act, and the system set up under it, are essentially not fulfilling the objects of the Act in accordance with the reasons the Australian Parliament passed the legislation. These reasons are set out in the preamble to the Native Title Act. The result is that Indigenous people are not able to fully exercise and enjoy human rights.

Much good work is being done. Agreements are being entered into that benefit Indigenous people. Determinations of native title are being made that recognise Indigenous peoples rights and interests in land and waters held under their traditional laws and customs. The native title system is being used to deliver economic, social and cultural outcomes to Indigenous people.

Some of the ‘community’ of parties involved in native title together with their interactions. Click here for larger image.

However, there are two overarching constraints on the capacity of the native title system to fully deliver recognition and protection of native title:

- the law, both the Native Title Act, and the common law as it has evolved and interpreted the Native Title Act; and

- the design of the system, the way it operates, and the processes established under it.

Both of these are amenable to political solutions.

- The first constraint is the Native Title Act and the development of the common law. These have not been comprehensively addressed in any of the recent reviews and changes to the native title system undertaken by previous governments. The Native Title Act is too complex. The common law as developed by the courts has placed almost insurmountable barriers in the way of Indigenous people seeking recognition and protection of their native title, and compensation where it has been extinguished (some common law barriers are considered in later chapters of this report). As the Hon. Mary Gaudron QC has pointed out:1

[T]o embark on an analysis of native title law is to begin with the strange and unfamiliar. It is to begin with the notion of rights which owe their existence, not to our laws which are strange enough, but to customs and traditions in respect of which we have contrived, by and large, to remain comfortably ignorant. ... It is the Native Title Act that provides the framework by reference to which [the] recognition and protection [of native title rights] are secured. To describe that framework as ‘exceedingly complex’ ... is, perhaps, a masterful understatement. Yet the statutory framework is necessarily complex. ...The legal practitioner who ventures into this field must know not only the detail of the Native Title Act, but must also have a thorough understanding of the common law system of tenure and its different estates as well as the various statutory schemes by which the several States and Territories have, from time to time, provided for the creation of private interests in and for the use by governments and individuals of public lands. There is, I think, no more demanding or difficult area of law.

This is a piece of legislation that is intended to be a special measure for the benefit of Indigenous people. The most disadvantaged Australians, many of whom may not speak English as a first language, have to contend with one of the most complex pieces of legislation in Australia to gain legal recognition of their native title rights and interests.

- The second constraint is the system and how it operates. Elements of the system have been the subject of a number of reviews and reports over the years. The system has been subject to significant changes since the previous government announced in 2005 that it was ‘reforming’ the native title system. The changes have been targeted at the efficiency and effectiveness of the system. I have concerns about both the process by which the changes were undertaken, and the possible outcomes from the changes. It is still too early to assess the impact of the changes. The changes to different elements of the system are dealt with in later chapters of this report.

Some insight into these two constraints may be gained from observations made by a number of Federal Court judges who have long experience dealing with native title cases. Other participants in the native title system also provide insight into the operation of the Native Title Act, the system it establishes, and the development of the common law. Some of these telling insights follow in the next sections of this chapter.

Any assessment of how well the system is working must always refer to:

- the preamble to the Act;

- the purpose of the Native Title Act;

- the main objects of the Act; and

- the reasons the Australian Parliament enacted the legislation (to give effect to the Mabo decision).

They must be kept foremost in mind whenever contemplating changing the system, or assessing past changes. The human rights of Indigenous people are inalienably connected to the Act and the reasons the Australian Parliament passed it. This is why the parliament gave me the responsibility of reporting on the operation of the Act, and its effect on the exercise and enjoyment of the human rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.2

Purpose of the Native Title Act

The Commonwealth’s major purpose in enacting this legislation [the Native Title Act] is to recognise and protect native title. ...3

The purpose of this Bill is to provide a national system for the recognition and protection of native title and for its co-existence with the national land management system.4

The purpose of the Native Title Act is clearly set out in the Explanatory Memorandum to the Native Title Bill 1993. The former prime minister, Paul Keating, reinforced this as the purpose when he introduced the Bill into the Australian Parliament. He said that a key aspect of the Bill was:

… ungrudging and unambiguous recognition and protection of native title.5

Reasons why the Native Title Act was enacted are set out in the preamble.

At the beginning of this Bill and before the substantive clauses there is a statement which sets out some of the reasons why this legislation is being enacted. The preamble describes the dispossession of the indigenous inhabitants of this country. The preamble notes the making of the decision in Mabo and the Australian peoples desire to rectify the injustices of the past. The preamble also refers to the fact that this legislation is intended to be a special measure for the descendants of the original inhabitants of Australia as allowed by s.51(xxvi) of the Constitution and a special measure for the advancement and protection of those peoples in accordance with the International Convention on All Elimination of Forms of Racial Discrimination [sic].6

The Australian Government intended that the Native Title Act comply with Australia’s international obligations.

The legislation complies with Australia’s international obligations, in particular under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. As indicated in the preamble, the legislation constitutes a special measure under the Racial Discrimination Act for the benefit of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people—providing as it does significant benefits such as special processes for determining native title; protection of native title rights; just terms compensation for any extinguishment of native title; a special right of negotiation on grants affecting native title land; designation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations to assist claimants; and establishment of a national land fund.7

This is the framework in which to understand the Native Title Act. It is the framework in which any changes to the Native Title Act need to be placed and referred against. Before considering changes, a review of some aspects of the current ‘state of play’ provides an additional context in which to assess the native title system.

Native title: the state of play?

That the state of play is tortuous is highlighted by the comments of the judges in the Rubibi8 and Wongatha9 cases.

The Rubibi case

Under Australian law, the Yawuru peoples commenced their claim for recognition of their traditional connection to, and ownership of, their country on 2 February 1994. After an ‘epic struggle’ – as described by Justice Merkel (who determined their claim) – the final determination of their claim was made twelve years later in 2006.10

The Yawuru claimants were largely successful in their native title claim. That is:11

… the claim has succeeded in whole or in part over approximately 4900 sq kms of their traditional country in and around Broome. The Yawuru claimants have established a communal native title entitlement to exclusive possession of their traditional country.

[However]:

… as a result of the criteria laid down under Australian law for extinguishment of native title, the native title of the Yawuru community was partially or totally extinguished in relation to significant parts of the Yawuru claim area. Also, as a native title right to exclusive possession is not recognised under Australian law in respect of the inter-tidal zone and, subject to some exceptions, areas that have been subject to pastoral or mining leases, the native title rights and interests in respect of most of those areas are not exclusive.

The judge went on to describe the native title system as being in a state of gridlock.12

The fact remains that there are presently 608 applications in relation to native title awaiting resolution in the Court. Most of those applications have been before the Court a considerable time. Four of those applications are either part heard or are reserved for judgment and only one is fixed for a final hearing this year. It follows that 603 of the 608 applications presently before the Court have no final hearing date fixed in the reasonable foreseeable future. In these circumstances, it is fair to describe native title in Australia as being in a state of gridlock.

Although Justice Merkel made these observations in March 2006, the situation remains much the same at 30 June 2007, the end of the reporting period for this report. At that date there were 532 claimant applications, 35 non-claimant applications, and 11 compensation applications at some stage between filing in the Federal Court and resolution. Difficulties with the law and the process for obtaining a determination of native title continued to be highlighted over 2006 and 2007.

The Wongatha case

In the Wongatha case there were eight overlapping claimant applications before the Federal Court for determinations of native title. The first application claiming native title, which was on behalf of the Wajlen people, was filed in August 1994. The Wongatha claim was the consolidation of a number of proceedings (see the chapter later in this report on significant Federal Court cases). It related to some 160,000 square kilometres of land. Possibly half to two-thirds of the land is spinifex country. The rest is characterised by mulga, rock-holes and breakaways. It is used for pastoral activities and mining. The land is generally in the Goldfields region about 85 kms north of Kalgoorlie.13 The other seven applications overlapped the area of the Wongatha claim to some extent.

The judge disposed of the Wongatha claim and one other to finality on 5 February 2007. The other six claims he disposed of to the extent that they overlapped the area of the Wongatha claim. As the judge stated ‘[T]he case was lengthy’. There were approximately 17,000 pages of transcript of hearings (100 hearing days, often involving extended hours), 34 volumes of experts’ reports comprising 2,817 pages, and 97 volumes of submissions comprising 8,087 pages (including appendices and annexures).14

After all this, the court found that seven of the claims were not properly authorised. That is, the people who brought the claims were not properly authorised to do so by the Indigenous people placed on the applications as the native title claimants. One wonders how and why the system allowed this to occur.

There was no determination of native title. Whether Australian law would recognise the native title of other native title claimants grouped differently, was not decided. Although the judge did consider all the claims on their merits he did not determine the claims. Rather the possibility that native title might be recognised if claimed by Indigenous people, grouped into different claim groups to those before the judge, was left open.

Hearing and resolving the case exposed the judge to what he considered to be:

an unsatisfactory state of affairs in the native title area. Perhaps the heart of the problem is that the legal issue that the Court is called upon to resolve is really only part of a more fundamental political problem.15

The judge in the Wongatha case drew attention to some issues relating to native title proceedings generally. These include:

- The creation of expectations (that may not be met).

- The appearance of unequal treatment as between different groups of Indigenous people. This arises because each native title case depends on its own facts and the history of its claimants and their ancestors. The judge gave three examples of this:

– A difference between the date of sovereignty and the date of European settlement may result in the absence of substantial written records. This will make it harder to prove Indigenous laws and customs as they existed at sovereignty. This problem will not be as evident where the date of European settlement and sovereignty are the same. (The date of sovereignty in the Goldfields is taken to be 1829. The date of European settlement, 1869.)

– Some native title cases are strongly contested, others are not. The reason relates to the value of land to others, and has nothing to do with the respective merits of the different cases.

– Migration and population shift, driven by necessity or desire, may result in claimants not being able to prove that their ancestors lived in the area over which native title is claimed. This will differ across Australia.

The tribunal and other commentators

The National Native Title Tribunal (the tribunal) has also presented a sobering picture of the native title system. The tribunal noted in its 2005-2006 annual report, and again in its 2006-2007 report that:

- At the rate that native title applications have been resolved to date, it will take many years to resolve outstanding applications and many older Indigenous Australians will not see their claims finalised.

- Clients and stakeholders can become frustrated at delays and the high cost of participating in the native title system.

- Native title determinations often deliver few direct benefits to Indigenous Australians and most determinations, in isolation, fall short of claimants’ aspirations.16

Other criticisms of the system and the law, include:17

- that Indigenous people are forced to prove what they already know;

- that Indigenous knowledge is transferred to non-Indigenous experts and then controlled by the ‘experts’;

- the legal barriers to obtaining recognition of native title make it too difficult;

- the Native Title Act fails to really protect native title;

- it causes conflict between Indigenous people and with non-Indigenous people; and

- involvement in native title claims drains considerable energy away from transferring Indigenous knowledge to the next generation of Indigenous people.

Traditional owners experience

In my previous report I set out findings from a national survey of traditional owners conducted by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission: the National Survey on Land, Sea and Economic Development.18 A number of the findings are important in this discussion of the native title system:

- The most important land priority for traditional owners is custodial responsibilities and capacity to either live on, or access the land.

- A majority of traditional owners do not have a good understanding of the agreements on land.

- The top three reasons preventing traditional owners from understanding land agreements are (in descending order):

- lack of understanding of native title legal terminology and process;

- the process lacks Indigenous perspective; and

- lack of information.

Native title is at the heart of recognition by Australian law of traditional owners’ custodial responsibilities for land and waters. A system that is not delivering fully on recognition and protection of native title is failing Indigenous people by not recognising the most important land priority of traditional owners.

The findings from the survey, that traditional owners do not understand the agreements they are entering into primarily because they lack understanding of native title legal terminology and process, reinforce my concerns regarding the complexity of the Native Title Act and the processes established by it.

Native title outcomes

In the context of the previous comments it is worth reviewing the outcomes of the native title system up until 30 June 2007. As we commemorate the fifteenth anniversary of the Mabo decision, which resulted in the Native Title Act, there have been a number of determinations that native title exists, and many more agreements made about access to lands and waters and the use of them.

Native title applications and determinations

Between the commencement of the Native Title Act on 1 January 1994 (up to 30 June 2007) a total of 1,750 native title applications were made. These comprised claimant, non-claimant, compensation, and revised native title determination applications. The following table shows native title applications since the start of the Native Title Act.19

Native title applications since 1993 |

||

|

Type of application |

Applications made |

Applications finalised* |

|---|---|---|

|

Claimant |

1,454 |

922 |

|

Non-claimant |

262 |

227 |

|

Compensation |

33 |

22 |

|

Revised native title determination |

1 |

1 |

Total |

1,750 |

1,172 |

* Finalised includes discontinued, dismissed, withdrawn, rejected, struck-out, combined with other applications or the subject of non-approved or fully-approved native title determinations.

As at 30 June 2007, 532 claimant applications, 35 non-claimant applications, and 11 compensation applications were at some stage between filing and resolution.20 The following matters were being registered:

- 425 applications on the Register of Native Title Claims;

- 103 determinations were on the Native Title Register, including

- – 68 determinations where native title does exist, and

- – 35 determinations where native title does not exist; and

- 280 agreements were on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements.21

Over the reporting period (2006-2007 financial year) there was a total of 16 native title determinations registered. This compares to 21 during the 2005-2006 financial year reporting period. This year’s outcomes are comprised of:

- eight consent determinations (including seven that native title exists);

- one litigated determination that native title exists; and

- seven which were unopposed (non-claimant).22

Native title applications made and finalised in 2006-2007 are shown in the following table.

Native title applications made and finalised in 2006-2007 |

||

|

Type of application |

Applications made |

Applications finalised* |

|---|---|---|

|

Claimant |

30 |

50 |

|

Non-claimant |

11 |

15 |

|

Compensation |

1 |

2 |

Total |

42 |

67 |

* Finalised includes discontinued, dismissed, withdrawn, rejected, struck-out, combined with other applications or the subject of non-approved or fully-approved native title determinations.

Indigenous land use agreements

The 1998 amendments to the Native Title Act extended the agreement-making ability to include Indigenous land use agreements (ILUAs). ILUAs are voluntary agreements between native title groups and others about the use and management of land and waters. According to the President of the National Native Title Tribunal the number of Indigenous land use agreements has doubled over the last two years with more than 300 ILUAs registered across most States and Territories, covering more than 11 percent of the country (as at October 2007).23 All Indigenous land use agreements are shown in the following table.

Indigenous land use agreements up to October 2007 |

|||||||||

|

Type of Agreement |

ACT |

NSW |

NT |

QLD |

SA |

TAS |

VIC |

WA |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fully concluded ILUA and use and access agreement negotiations |

3 |

12 |

6 |

1 |

22 |

||||

|

Milestone agreements* in ILUA negotiation outside NTDAs** |

1 |

24 |

25 |

||||||

|

Milestone agreements* in ILUA negotiations with NTDAs** |

2 |

6 |

28 |

222 |

1 |

259 |

|||

Total |

5 |

6 |

41 |

252 |

2 |

306 |

|||

* Milestone agreements are those agreements leading to a final agreement, where the tribunal provided negotiation assistance.

** native title determination applications

During the 2006-2007 financial year, 22 ILUA negotiations were concluded. This is an increase from the 2005-2006 financial year where 19 ILUAs were concluded.24

In accordance with the Native Title Act each registered ILUA has effect as if it were a contract among the parties. All native title holders for the area covered by the terms of the agreement are legally bound, whether or not they are parties to the agreement. Once an ILUA negotiation is concluded, the Native Title Registrar must apply a compliance test to determine that it is ready to be registered and included on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements.

Compliance criteria includes:

- making sure that the registration requirements of the Native Title Act and regulations are met;

- that the public and those who may have an interest in the area of the proposed ILUA have been notified; and

- consider any objections to the registration of the ILUA.25

ILUAs lodged or registered in 2006-2007 are shown in the following table.

ILUAs lodged or registered in 2006-2007 |

|||||||||

|

ILUAs |

ACT |

NSW |

NT |

QLD |

SA |

TAS |

VIC |

WA |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ILUAs lodged |

3 |

3 |

28 |

6 |

4 |

1 |

45 |

||

|

ILUAs registered |

1 |

14 |

7 |

7 |

2 |

31 |

|||

Native title agreements and related agreements

There are other native title agreements which are not ILUAs. The National Native Title Tribunal describes these agreements as:

- full consent determinations that provide for the recognition of native title for alternative resolutions of claimant applications, as well as other agreements that fully resolve native title determination applications;

- agreements between parties that set the groundwork for more substantive outcomes in the future and may lead to the resolution of native title determination applications, for example agreements on specific issues, process or frameworks; and

- agreements for compensation for the loss or impairment of native title and agreements that allow for, and regulate access by, native title holders to certain areas of land.26

The following table shows native title agreements to 30 June 2007.27

Native title agreements to 30 June 2007 |

|||||||||

|

Type of agreement |

ACT |

NSW |

NT |

QLD |

SA |

TAS |

VIC |

WA |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Agreements that fully resolve native title determination applications |

3 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

18 |

||

|

Agreements on issues, leading towards the resolution of native title determination applications |

15 |

10 |

72 |

27 |

1 |

22 |

147 |

||

|

Process/ framework agreements |

6 |

6 |

83 |

36 |

14 |

57 |

202 |

||

Total |

24 |

22 |

157 |

64 |

16 |

84 |

367 |

||

Future act agreements

Future act agreements allow activities such as exploration or mining tenements to proceed. They may also be agreements that facilitate the reaching of milestones during the mediation of a future act application and that lead to the final agreement.

The following table shows future act agreements negotiated in 2006-2007.28

Future act agreements negotiated in 2006–2007 |

|||||||||

|

Type of agreement |

ACT |

NSW |

NT |

QLD |

SA |

TAS |

VIC |

WA |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Agreements that fully resolve future act applications |

7 |

1 |

106 |

114 |

|||||

|

Milestones in future act mediations |

11 |

53 |

64 |

||||||

Total |

18 |

1 |

159 |

178 |

|||||

There are two types of future act right to negotiate applications:

- Section 35 future act determination application; and

- Section 32(3) expedited procedure objection application.

The tribunal is responsible for making determinations that a future act may or may not go ahead and whether there will be specific conditions placed on parties where it is decided that a future act may be done.29

The following table shows future act determination application outcomes in 2006-2007.30

Future act determination application outcomes 2006-2007 |

|||

|

Tenement outcome |

QLD |

WA |

Total 2006-07 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Application not accepted |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Application withdrawn |

6 |

6 |

|

|

Consent determination – future act can be done |

169 |

169 |

|

|

Consent determination – future act can be done subject to conditions |

5 |

5 |

|

|

Determination – future act can be done |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Dismissed – s148(a) no jurisdiction |

6 |

6 |

|

Total |

5 |

183 |

188 |

Data are only available for Western Australia and Queensland because they receive the majority of future act right to negotiate applications. All of the determinations in Queensland and the majority of those in Western Australia have been by consent.

Section 237 of the Native Title Act provides for an expedited procedure which is triggered when a government party asserts in a public notification that the expedited procedure applies to a tenement application. Consequently, the right to negotiate does not apply. The Act also provides a mechanism whereby registered native title parties can lodge an objection to this assertion.

Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland use the expedited procedure. Other states have either developed alternative state provisions, which include provisions to process tenements considered to have minimal interference or impact, or they have opted not to use the expedited procedure provisions.31

The following table shows objection application outcomes in 2006-2007.32

Objection application outcomes 2006-2007 |

||||

|

Tenement outcome |

NT |

QLD |

WA |

Total 2006-07 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Consent determination – expedited procedure does not apply |

6 |

6 |

||

|

Determination – expedited procedure applies |

7 |

7 |

||

|

Determination – expedited procedure does not apply |

7 |

7 |

||

|

Dismissed – Section 148(a) no jurisdiction |

5 |

47 |

52 |

|

|

Dismissed – Section 148(a) tenement withdrawn |

2 |

67 |

69 |

|

|

Dismissed – Section 148(b) |

126 |

126 |

||

|

Expedited procedure statement withdrawn |

6 |

19 |

25 |

|

|

Expedited procedure statement withdrawn – Section 31 agreement lodged |

48 |

48 |

||

|

Objection not accepted |

2 |

2 |

||

|

Objection withdrawn – agreement |

6 |

28 |

507 |

541 |

|

Objection withdrawn – external factors |

1 |

1 |

||

|

Objection withdrawn – no agreement |

24 |

36 |

60 |

|

|

Objection withdrawn prior to acceptance |

1 |

60 |

61 |

|

|

Tenement withdrawn |

11 |

11 |

||

Total |

6 |

125 |

885 |

1,016 |

Native title: What might be claimed?

The High Court’s decision in the Mabo case and the enactment of the Native Title Act by the Australian Parliament raised high expectations amongst Indigenous peoples and strong fears amongst some in the non-Indigenous community. From this starting point the land over which native title rights and interests may be claimed and are likely to be recognised has come to be far less than, perhaps, was first imagined. Further, where there is a conflict, native title has been construed as the lesser title, giving way to all other titles. Today the National Native Title Tribunal informs people that:

Native title may exist on:

- vacant (unallocated) crown land;

- some state forests, national parks and public reserves depending on the effect of state or territory legislation establishing those parks and reserves;

- oceans, seas, reefs, lakes and inland waters;

- some leases, such as non-exclusive pastoral and agricultural leases, depending on the state or territory legislation they were issued under; and

- some land held by or for Aboriginal people or Torres Strait Islanders.

Generally speaking, full native title rights resembling something like freehold ownership will only be available over some vacant crown land, certain Aboriginal reserves and some pastoral leases held by native title holders. This means that, for most of the areas where native title is successfully claimed, the country will be shared by the native title holders and other people with rights and interests in the same area. This sharing is sometimes called coexistence.

Native title rights and non-native title rights can be recognised over the same area, but the native title rights cannot interfere with other interest holders.33

And the state of play?

In the last few pages of this chapter I have looked at the native title system today, from different perspectives. A casual reading suggests a system that is functioning. It is producing outcomes for Indigenous peoples. There have been determinations of native title and agreements on the use of and access to land and water. These agreements have provided other economic, social and cultural benefits.

However, the system may rightly be said to be in gridlock. It is moving very slowly, costing a lot in time, energy, emotion and resources. The native title rights and interests Indigenous peoples are obtaining are limited, and the land over which those rights and interests are recognised is very restricted. The common law barriers to recognition are prohibitive – as they are to obtaining compensation through litigation.

The previous government recognised the time it was taking to resolve native title matters and the cost – hence its ‘reform’ process. What appears to have been absent was a focus on whether the system was meeting the objects of the Native Title Act. The preamble to the Act – the reasons the legislation was passed – seems to have been forgotten.

From the perspective of human rights and equal opportunity, I cannot say that the system is providing effectively for the recognition and protection of native title.

The changes to the system

The former Commonwealth Attorney-General announced plans for ‘reform’ to the native title system in 2005.

The areas of the system the government has focused its changes on are:

- the claims resolution process;

- particular Indigenous representative bodies (representative Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander bodies and prescribed bodies corporate (PBCs));

- the funding of respondents to native title claims; and

- communication between Federal, state and territory governments.

Primarily, the changes have been directed at the problems of delay in resolving native title matters and the cost of doing so. The main changes made to different elements of the system are dealt with in later chapters of this report.

There were six inter-connected aspects to the ‘reforms’:

The claims resolution process: An independent review of the claims resolution process to consider how the tribunal and the Federal Court can work more effectively in managing and resolving native title claims.

Non-claimants (respondents) funding: Amending the guidelines to the native title respondents financial assistance program to encourage agreement-making rather than litigation.

Native title representative bodies: Measures to improve the effectiveness of representative Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander bodies (also referred to as native title representative bodies (NTRBs)).

Prescribed bodies corporate: An examination of current structures and processes of prescribed bodies corporate (PBCs) including targeted consultation with relevant stakeholders.

Consultation with state and territory governments: Increased dialogue and consultation with state and territory governments to promote and encourage more transparent practices in the resolution of native title issues.

Technical amendments to the Native Title Act: Preparation of an exposure-draft of legislation for consultation on possible technical amendments to the Native Title Act to improve existing processes for native title litigation and negotiation.

The policy intent underpinning the plans for change, as stated by the Australian Government, was to ‘achieve better outcomes for all parties involved in native title’ by putting in place ‘measures that will ensure native title processes work more effectively and efficiently’.34 The changes were intended to promote the resolution of native title issues, wherever possible through agreement in preference to litigation.35 There was the expectation that the cost of native title matters would be reduced and the time taken to resolve them shortened.

Wide-ranging legislative and administrative changes were made during the reporting period to implement the ‘reforms’.

Two pieces of legislation were passed by the Australian Parliament during the reporting period to implement parts of the ‘reforms’: the Native Title Amendment Act 2007 (Cth) (NTAA) and the Native Title Amendment (Technical Amendments) Act 2007 (Cth) (Technical Amendments Act).

Native Title Amendment Act 2007 The majority of the provisions of the NTAA came into effect on the 15 April 2007.36 They deal mainly with:

- representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies (Schedule 1);

- the claims resolution process (Schedule 2);

- prescribed bodies corporate (Schedule 3); and

- funding under Section 183 of the Native Title Act (respondent funding)

(Schedule 4).

Native Title Amendment (Technical Amendments) Act 200737 The Technical Amendments Act was passed by the Australian Parliament on 20 June 2007 and received Royal Assent on 20 July 2007. The commencement date for the amendments has been staggered. A small number commenced retrospectively on 15 April 2007 while other amendments came into effect on 1 July, 21 July (affecting PBCs and NTRBs), and 1 September 2007. The main areas covered by the Technical Amendments Act are:38

- amendments to provisions applying to NTRBs to complement measures in the NTAA; and

- partial implementation of two of the recommendations from the Report on the Structures and Processes of PBCs.

Administrative changes made to the native title system are covered more fully in the chapters of this report dealing with changes to different elements of the system.

The changes made by the Technical Amendment Act have only been touched on briefly in this report as they are outside of the reporting period. However, I do have some initial concerns about the process. It appears that some of the amendments are substantial enough that they do not warrant the term technical amendments. I am concerned that by putting these in a technical amendment Bill they may have been the subject of less parliamentary scrutiny than if they were placed, more appropriately, in the NTAA.

Concerns about the changes

Although it is still too early to determine the effect of the changes, they raise a number of concerns.

General concerns

There are a number of general concerns I have about the changes:

- Recognition and protection of native title was not placed at the centre of the Australian Government’s ‘reform’ agenda.

- Imperatives of government drive the changes, rather than those of Indigenous people and their human rights.

- A more efficient and effective system may be of benefit to Indigenous people. As may saving time and money in the resolution of matters. However they are not appropriate ends in themselves.

- The previous government did not direct its change process, nor target its changes, toward the protection and recognition of native title. This is the first of the four main objects of the Native Title Act. Nor does it appear to have kept in mind, and been guided by, the preamble to the Native Title Act.

- The efficiency and effectiveness, towards which the changes have been directed, may result in faster, cheaper ‘processing’ of native title issues and claims. It is not necessarily going to result in greater protection and recognition of native title. The changes to the system have not been directed to that end.

Specific concerns

I also have specific concerns about some of the changes to the different areas of the system. These are dealt with in the chapters in this report covering each of the elements of the system subject to changes.

The changes have been undertaken by the Australian Government with the stated intent of improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the system and of promoting agreement-making in preference to litigation. They have been undertaken because of widespread concerns at the length of time taken for resolution of native title matters, and the cost of running the system. The changes have not been primarily driven by the intent to ensure that the native title system delivers to Indigenous people recognition and protection of their native title rights and interests.

One of the main objects of the Australian Parliament in passing the Native Title Act in 1993 was to provide for the recognition and protection of native title. Any changes of the system established under that Act must be driven and measured by the extent to which it is delivering on that object. Any increase in the timely, efficient and effective resolution of native title matters may be in the interests of Indigenous people but not if it results in faster, more efficient and effective extinguishment of native title or failure to gain recognition of it.

Timeliness, efficiency and effectiveness must be in the service of recognition and protection of Indigenous peoples’ native title.

Promoting agreement in preference to litigation may assist Indigenous people to gain recognition of their native title. However an increase in the number of agreements and a reduction in litigated determinations do not necessarily mean there has been an increase in the ease with which Indigenous people are gaining recognition and protection of their native title rights and interests. It is quite possible to have an efficient and effective system resolving native title matters in a timely, economical manner through agreement-making which delivers little or no recognition of native title to Indigenous people.

The imperatives of government have driven the changes rather than the imperatives of Indigenous people and their exercise and enjoyment of human rights. As the native title system matures, its own operation becomes the focus rather than the outcome it was established to achieve.

The Australian Government, when announcing it was undertaking ‘reform’ of the native title system, conceptualised the ‘reforms’ as having six aspects. By doing this many aspects of the system have been left out despite the intent of the government to make the ‘reforms’ comprehensive. Aspects that are at the very heart of the system and go to the reason for its existence were not central to the change process and were not given much, if any, weight. These include the:

- effectiveness of the system in providing for the protection and recognition of human rights as measured by the nature of the rights and interests that are being recognised by the courts;

- experience of claimants or potential claimants for native title in utilising the system to obtain determinations of their native title or compensation for its extinguishment;

- quality, sustainability and enforceability of the agreements being entered into; and

- removal of impediments to Indigenous people obtaining recognition

of their native title rights and interests arising from the interpretation by the courts of the requirements of the Native Title Act.

Footnotes

[1] As quoted in Neate, G., An overview of native title in Australia – some recent milestones and the way ahead, paper delivered by the President of the National Native Title Tribunal at 11th Annual Cultural Heritage & Native Title Conference, Brisbane, Queensland, 21 July 2004, available online at: http://www.nntt.gov.au/metacard/1092114365_2688.html. The Hon Mary Gaudron QC was the only High Court justice to have heard and given judgment in relation to every native title case in the High Court from Mabo v Queensland (No 1) (1988) 166 CLR 186 to the Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 194 ALR 538; 77 ALJR 356.

[2] Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), s209.

[3] Native Title Bill 1993, Explanatory Memorandum, Part A, p1.

[4] Native Title Bill 1993, Explanatory Memorandum, Part B, p1.

[5] Native Title Bill 1993, Explanatory Memorandum.

[6] Native Title Bill 1993, Explanatory Memorandum.

[7] Hon Paul Keating, Hansard, House of Representatives, 16 November 1993, p2878, available online at: <http://parlinfoweb.aph.gov.au/piweb/viewdocument.aspx?ID=283806&TABLE=H…;

[8] Rubibi Community v State of Western Australia (No 7) [2006] FCA 459.

[9] Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v State of Western Australia (No 9) (207) 238 ALR 1.

[10] Rubibi Community v State of Western Australia (No 7) [2006] FCA 459, 28 April 2006, per Merkel J.

[11] Rubibi Community v State of Western Australia (No 7) [2006] FCA 459, 28 April 2006, per Merkel J, corrigendum.

[12] Rubibi Community v State of Western Australia (No 7) [2006] FCA 459, 28 April 2006, per Merkel J, corrigendum.

[13] Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v State of Western Australia (No 9) (2007) 238 ALR 1, per Lindgren J, summary, p1.

[14] Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v State of Western Australia (No 9) (2007) 238 ALR 1, per Lindgren J, summary, p1.

[15] Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v State of Western Australia (No 9) (2007) 238 ALR 1, per Lindgren J, summary, p2.

[16] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p25.

[17] Smith, B., Morphy, F., (eds), The Social Effects of Native Title: Recognition, Translation, Coexistence, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University, Canberra, Research Monograph No. 27 2007. Available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/c27_citation.html.

[18] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Native Title Report 2006, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, April 2006, Sydney.

[19] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p42.

[20] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p42.

[21] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p42.

[22] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p42.

[23] National Native Title Tribunal, 300 Indigenous land use agreements, Media Release, 25 October 2007, available online at http://www.nntt.gov.au/media/1193211263_2716.html, accessed 11 January 2008.

[24] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p49.

[25] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p63.

[26] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p51.

[27] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p52.

[28] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p58.

[29] These decisions or determinations also consider whether negotiations conducted to reach agreement about future act determination applications have occurred in good faith.

[30] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p66.

[31] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p67.

[32] National Native Title Tribunal, Annual Report 2006-2007, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2007, p66.

[33] National Native Title Tribunal, What kind of areas can be claimed in a native title application? NNTT Fact Sheet, available online at http://www.nntt.gov.au/publications/1036375662_1544.html, accessed 1 December 2007.

[34] Ruddock, P., (Attorney-General), Reforming the Native Title System, Media Release, 7 September 2005.

[35] Ruddock, P., (Attorney-General), Reforming the Native Title System, Media Release, 7 September 2005.

[36] The Native Title Amendment Bill 2006 was introduced into the House of Representatives by the Attorney-General on 7 December 2006. It was referred to the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs for inquiry and report by 23 February 2007. It was passed by the Australian Parliament after some amendments and received the Royal Assent on 15 April 2007.

[37] The Native Title Amendment (Technical Amendments) Act 2007 (Cth) was passed by the Australian Parliament on 20 June 2007 and received the Royal Assent on 20 July 2007. The commencement date for the amendments has been staggered. A small number commenced retrospectively on 15 April 2007. Other amendments came into effect on 1 July, 21 July (affecting PBCs and NTRBs), and 1 September 2007.

[38] The changes made by the Native Title Amendment (Technical Amendments) Act 2007 (Cth) are intended to improve the workability of Native Title Act rather than fundamentally altering the native title system. The government stated that in making the amendment it did not revisit the amendments rejected by the Senate in 1998.