Native Title Report 2004 : Annexure 2 : Promoting Economic and Social Development through Native Title

Annexure 2 : Promoting Economic and Social Development through Native Title

WORKSHOP HANDOUTS

CONTENTS

- Overview of the role of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner

- Definition and rationale of the project

- Strategies aimed at achieving social and economic development

- Human rights and development

1. Overview of the role of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner

Native Title Act 1993, s 209

...the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner report on the operation of the [NTA] and its effect on the exercise and enjoyment of human rights of Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders.

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Act, 1986, s.46A

The following functions are conferred on the Commission:

- to report on the enjoyment and exercise of human rights by Aboriginal persons and Torres Strait Islanders, and including recommendations as to the action that should be taken to ensure the enjoyment and exercise of human rights by those persons;

- to promote discussion and awareness of human rights in relation to Aboriginal persons and Torres Strait Islanders;

- to undertake research and educational programs, and other programs, for the purpose of promoting respect for the human rights of Aboriginal persons and Torres Strait Islanders and promoting the enjoyment and exercise of human rights by Aboriginal persons and Torres Strait Islanders;

- to examine enactments, and proposed enactments, for the purpose of ascertaining whether they recognise and protect the human rights of Aboriginal persons and Torres Strait Islanders, and to report to the Minister the results of any such examination.

The Commissioner's role is to provide an analysis of government action and its effect on the human rights of Indigenous Australians.

2. Definition and rationale of the project

Aims

- To assist traditional owner groups to achieve their economic and social development goals through native title.

Objectives

- To draft principles; based on internationally recognised rights of self determination, development, non-discrimination and protection of culture; to redirect the focus of native title agreements towards the economic and social development needs of the traditional owner group.

- Consult with relevant parties to develop and expand upon the draft principles in relation to agreement-making.

- Develop guidelines to assist governments and other stakeholders to formulate native title policies directed to sustainable social and economic development for traditional owners.

Outputs

- Discussion paper

- Consultations (exchange of information between Commissioner and various parties).

- Native Title Report 2004.

- (optional) Separate document with guidelines.

Why a policy approach?

- The Native Title Act and courts' interpretation of it, impose severe limitations on what can be gained through strictly-defined 'native title rights & interests'.

- Use existing policy approaches/international strategies/practitioner and claimant experience to increase potential for native title system and agreements to contribute to the economic and social development goals of traditional owner groups.

3. Strategies aimed at achieving economic and social development

State and Commonwealth government's policy relating to Indigenous Australians are being developed around a number of key terms. These terms include; partnerships, capacity development, good governance and sustainability. While these terms are widely used in the Australian policy context, they also are an important feature of the UN human rights system and have developed in jurisdictions similar to Australia. The discussion below provides a brief overview of the use of these terms in policies relating to Indigenous Australians and an overview of the use of these terms at an international level.

3.1 PARTNERSHIPS

Australian context

'Partnerships' are becoming a feature of Indigenous policy and programs. Cape York Partnerships and the Commonwealth's Whole of Government initiative promote co-operative relationships between Indigenous communities, government and industry. The Whole of Government initiative requires:

Indigenous communities and governments must work in partnership and share responsibility for achieving outcomes and building the capacity of people in communities to manage their own affairs.1

A Partnership Approach is also being adopted at a state level. In Western Australia, The Statement of Commitment to a New and Just Relationship between the Government of Western Australia and Aboriginal Western Australians is based on a Partnership Framework. The Statement of Commitment requires that partnerships:

- will be based on shared responsibility and accountability of outcomes;

- should be formalised through agreement;

- should be based on realistic and measurable outcomes supported by agreed benchmarks and targets;

- should set out the roles, responsibilities and liabilities of the parties; and

- should involve an agreed accountability process to monitor negotiations and outcomes from agreements.

Importantly, the Partnership Framework provides that the government 'will support Aboriginal people to negotiate regional and local agreements according to the priorities of Aboriginal people in partnership with other stakeholders'.

International context

The idea of partnerships is embedded within strategies to achieve sustainable development. The Rio Declaration and Agenda 21 identified the importance of partnerships. And the UN Commission on Sustainable Development has developed key criteria for partnerships. These criteria require that partnerships:

- are voluntary

- directed towards agreed goals

- supplement government commitments, not replace them

- reflect the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development

- are based on predictable and sustained resources.

More broadly, partnerships must be based on trust, respect, ownership and equality2.

In using a partnership approach - it is important to carefully manage the process to ensure the stronger partner does not impose its approach on the other. Where partnerships are between unequal partners the stronger partner may begin to impose inappropriate strategies, inappropriate training and rely solely on experts to get a project off the ground. In an international context, focus on ownership is being seen as a way in which the problems of an unequal partnership can be overcome:

A few years back, attempts to equalize [development] relationships resulted in the promotion of the term 'partnership' coupled with efforts to achieve local participation or empowerment. Now the clarion call is for 'ownership'.3

3.2 GOOD GOVERNANCE

The approach of Cape York Partnerships, demands that Cape York communities govern themselves.

For too long my people have been administered and governed by others. Now is the time we demand the right to take responsibility4.

Commonwealth and State initiatives stress the role of shared responsibility between Indigenous communities and government, without going so far as too promote Indigenous governance. However it is unlikely that programs directed only by government without Indigenous control of the economic and social development agenda will be sustainable.

The importance of Indigenous governance in sustained social and economic development has been documented by the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development. Founded in 1987, the Harvard Project aims 'to understand and foster the conditions under which sustained, self-determined social and economic development is achieved among American Indian nations'. From research and findings of the project, the most essential ingredient to sustained economic and social development is meaningful self government:

... the key factors are not the economic factors that many people might think would be most important - things like natural resource endowments or location or educational attainment. Those things certainly matter, but their significance rests on a foundation of political change5.

This approach to economic development is described as the 'nation building' approach and contrasts with a 'jobs and income' approach to economic development:

| 'Jobs and Income Approach' Reactive |

'Nation building approach' Proactive |

|---|---|

| Responds to anyone's agenda (from the govt or industry) | Responds to your agenda (from strategic planning for the long-term future) |

| Emphasizes short-term payoffs (especially jobs and income now) | Emphasizes long-term payoffs (sustained community well-being) |

| Emphasizes starting businesses | Emphasizes creating an environment in which businesses can last |

| Success is measured by economic impact | Success is measured by social, cultural, political and economic impacts |

| Development is mostly the tribal planner's job (planner proposes; council decides) | Development is the job of tribal and community leadership (they set the vision, guidelines, policy; others implement) |

| Treats development as first and foremost and economic problem | Treats development as first and foremost a political problem |

| The solution is money | The solution is a sound institutional foundation, strategic direction, informed action |

The project has also noted that:

Sustained and systemic economic development... does not consist or arise from building a plant or funding a single project. Economic development is a process, not a program.

This process focuses on community governance. The Harvard Project identifies key areas for effective governance:

- Sovereignty

Major decisions about governance structures, resource allocation and development are in the hands of Native American Indians. - Governing institutions

Self rule is not enough, it has to be exercised effectively, through stable rules, keeping community politics out of day to day business and administration and fair dispute resolution. - Cultural match

Governing structures need to have credibility within Indian society and resonate with indigenous political culture. They also must be accepted by the community or group as a legitimate governing institution. - Strategic thinking

The project identified the importance of developing long term strategic thinking and planning taking account of assets/opportunities and priorities/concerns. - Leadership

Finally the project identifies the need for Indigenous leadership that can envisage a different future, recognise the need for foundational change, are willing to serve the groups interest instead of their own and can communicate the vision to the rest of the group.

The emphasis of the Harvard Project is self governance. It argues that sustained social and economic development cannot be achieved without Indigenous control and governance. The project has also identified important structural features for an Indigenous governance model to be effective (listed above) and emphasizes the importance of process, against relying on projects to achieve sustained social and economic outcomes. Harvard recognises that this process must empower and give control to the group which aims to achieve sustainable outcomes.

3.3 CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT

The United Nations has a key responsibility in achieving sustainable development goals and uses capacity development strategies to achieve these goals in both the work of the United Nations Development Program and the UN Division for Sustainable Development. The UN system defines capacity development in the following way:

Capacity refers to the ability of individuals, communities, institutions, organizations, social and political systems to use the natural, financial, political, social and human resources that are available to them for the definition and pursuit of sustainable development goals.

Capacity building or capacity development is the process by which individuals, institutions and countries strengthen these abilities.6

Consistent with the principles of the Harvard Project, capacity development stresses the empowerment of the group to achieve sustainable development. Capacity development, as a process by which sustainable development might be achieved has two important features. First, capacity development centralizes the role of those who seek to achieve development goals. Within native title negotiations, this requires that traditional owners play a central role. Second, the pace and agenda of capacity development is determined by the capacity of the group to engage with the process and achieve goals. Capacity development requires not that sustainable development be 'delivered' but that those who seek to achieve development goals within their communities, are actively involved in setting the agenda and determining the outcomes.

Broadly, capacity development has five main principles, the process must:

- be based on a locally driven agenda;

- build local capacity;

- involve ongoing learning and where appropriate adaptation of goals and agenda;

- be a long term investment

- integrate activities (through the creation of partnerships) at various level to address complex problems.

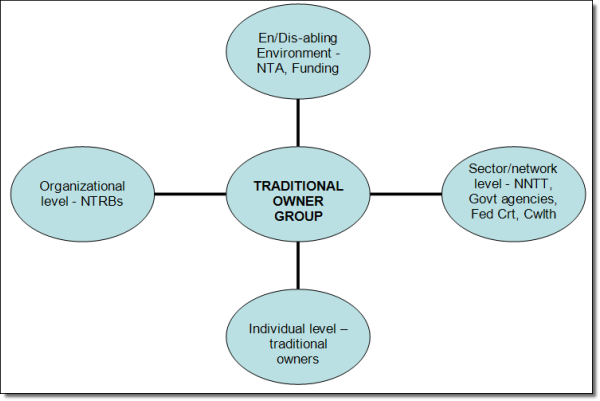

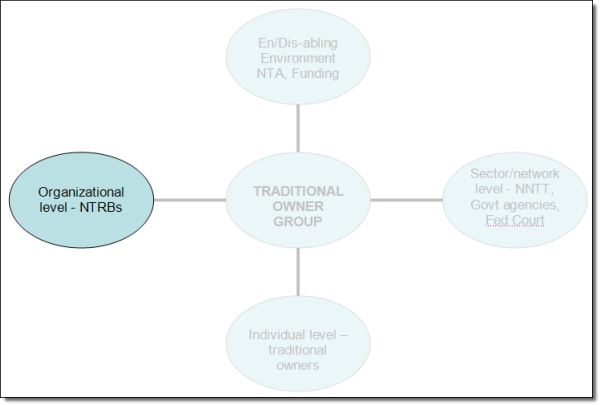

The last of these principles, highlights the importance of cross sector cooperation to implement capacity development. Without support at various levels within a system, capacity development strategies can fail. Within a native title context this requires support for capacity development from NTRBs, government, companies and administrative agencies such as the NNTT or Federal Court.

CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT AND NATIVE TITLE

In Australia, policy makers have begun to discuss the role of capacity development and its utility for Indigenous policy approaches. For the most part, these discussions have struggled to establish a clear definition or understanding of capacity building or capacity development. The differences between capacity building and capacity development can be clearly illustrated in a native title context. Capacity building more often refers to developing capacity within an organisation, amongst its staff and decision-makers. This can be distinguished from the capacity development model discussed above which adopts a system approach to promote the capacity development of those who seek to achieve their own sustainable outcomes.

CAPACITY BUILDING AND NATIVE TITLE

The ATSIS Native Title Capacity Building project is consistent with a capacity building approach as it aims to build capacity within NTRBs, addressing priority areas: corporate and cultural governance, management and staff development, native title technical training, collaborative training and research/applied capacity building.7 While these areas are essential for the effective operation of NTRBs, the capacity building program does not aim to build the capacity of the traditional owner group.

At the broader Indigenous policy level, capacity building is seen as an important component of social and economic development. In June 2004 the House of Representative Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs released its report - 'Many Ways Forward: Report of the Inquiry into capacity building and service delivery in Indigenous communities'. The report stressed the need for capacity building within government, Indigenous organisations and communities to ensure better management and greater responsiveness to service delivery issues. It concluded that capacity building include both 'activities which seek to empower individuals and whole communities while building the operational and management capacity of both organisations and governments' to assist in this process.

The approach set out by the Inquiry is consistent with the international strategy for capacity development and the Harvard project - emphasizing the crucial role of governance and control by the group who is aiming to achieve sustained social and economic development. In its appearance before the Standing Committee, Oxfam stated that:

Capacity building is not just training and it is not simply about individual and collective skills development. Capacity building is about community development and is essentially a political process.

3.4 SUSTAINABILITY

There are two aspects of sustainability that provide useful strategies for Indigenous communities. First, sustainability promotes a long term, holistic development approach that addresses social, economic, environmental, political and cultural dimensions of development. Second, sustainability is broadly supported by governments and industry, providing a foundation for traditional owners to negotiate for more 'sustainable' outcomes through native title.

Long term and holistic development approach

Sustainable development recognises three broad pillars of development - economic, social and environmental protection. The social pillar can also be further defined to include spiritual, cultural and political dimensions. Article 6 of the United Nations Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development states:

We are deeply convinced that economic development, social development and environmental protection are interdependent and mutually reinforcing components of sustainable development.

Research8 in Australia has examined the implications of sustainable development within Indigenous communities. This research highlights two important areas: the need to incorporate social, cultural, political issues within economic development strategies for Indigenous communities and; the opportunity to develop models of development that do not focus on traditional economic outcomes but can also focus on social and cultural development outcomes.

This research recognises that policies focused on economic development outcomes for Indigenous communities that have not given attention to social and cultural issues have often been unsuccessful. Sustainable development provides a framework which recognises the importance of addressing social, cultural, economic and environmental issues when aiming to achieve development goals.

Sustainability will require the achievement of a balance between three variables: commercial success (with limits placed on commercialism); the resilience of cultural integrity and social cohesion; and the maintenance of the physical environment.9

Sustainable development is also widely supported by industry and government. Although definitions of sustainable development are as widespread as its support, there are a number of principles established by the international sustainable development declarations.

Key sustainable development declarations since 1972 include:

- UN General Assembly, World Charter for Nature, 1982

- Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, 1992. Endorsed by UN General Assembly, 1992

- Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development, 2002. Prepared by the UN Commission on Sustainable Development.

For the most part the declarations have emphasized that people are at the core of sustainable development. This emphasis has become much clearer in the Johannesburg Declaration which focuses on the role of poverty in undermining sustainable development and the realization of rights. Consequently, the emphasis of sustainable development has substantially shifted towards poverty eradication.

Indigenous rights have an unmistakable role within sustainable development. The 1987 Brundtland report, Our Common Future recognised that Indigenous peoples were particularly at risk from development and emphasized the need to both protect Indigenous rights and learn from Indigenous perspectives of land. This approach was reflected in principle 22 of the Rio Declaration:

Indigenous people and their communities and other local communities have a vital role in environmental management and development because of their knowledge and traditional practices. States should recognise and duly support their identity, cultural and interests and enable their effective participation in the achievement of sustainable development.

This approach has been reiterated in the Johannesburg Declaration 2002 and supported in international complaints proceedings. In a complaint to the UN Human Rights Committee by Bernard Ominayak and the Lubicon Band against Canada the Committee found that the sale of gas and oil concessions by Canada on the traditional land of the Lubicon was in violation of Article 2710. The Committee reasoned that historic inequalities and the recent sale of concessions were threatening the way of life of the Lubicon and were therefore inconsistent with Article 27. Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, protects the culture of minority groups. The UN Human Rights Committee has interpreted this article in relation to Indigenous groups and observed that:

... culture manifests itself in many forms, including a particular way of life associated with the use of land resources, especially in the case of indigenous peoples... The enjoyment of those rights may require positive legal measures of protection and measures to ensure the effective participation of members of minority communities in decisions which affect them. 11

In a similar case, the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights heard a complaint brought on behalf of the Yanomani peoples of Brazil.12 The Yanomani claimed that the construction of a highway; the exploitation of resources on their traditional land and; the resultant damage to their environment and traditional way of life was in violation of the American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man. The Commission found in favour of the Yanomani, concluding that the development on their traditional land violated their right to life, liberty and personal security; the right of residence and movement and; the right to preservation of health and well-being.

4. Human rights basis for economic and social development

The Right to Development is the basis for a human rights approach to economic and social development. Declared by the UN General Assembly in 1986, the Right to Development refocuses development on the realization of all human rights. For example, a human rights approach to economic development promotes protection and respect for culture within economic development strategies. Strategies of this kind may include; commercial customary harvesting, Indigenous land management and art and craft enterprises. A human rights approach to social outcomes emphasizes the importance of effective Indigenous participation and control of initiatives aimed at social development. The diagram below sets out the right to development - its focus and relationship to other human rights standards.

4.1 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT - NATIVE TITLE CONTEXT

The human rights set out in the diagram apply to native title in the following ways:

Participation

- Notification, consultation and right to negotiate provisions of the NTA provide a limited form of free, prior informed decision making but are not adequate to satisfy human rights standards.

- Free, Prior and Informed Consent requires:

- No coercion or manipulation of the traditional owner group by external parties, either government or companies.

- Future act notification to occur allowing enough time for a group to reach informed consent.

- All members of the group provided with information setting out details of project and proponent.

- The group must be able to say No to the project.

- All members of the group must involved in the decision to withhold or provide consent.

Economic, social and cultural rights

- Importantly, the primary obligation for the realization of these rights falls on governments.

- NTA provides some basis for the recognition of economic, social and cultural rights by recognizing native title rights to hunt, conduct cultural activities and use the resources of land. Agreements provide further scope to build on these rights.

- The realization of economic, social and cultural rights is progressive. Improved standards in health, access to employment and housing is achieved by a process of incremental improvements - not necessarily by a one off large scale project.

- Native title negotiations provide an opportunity to begin a process of promoting these rights within traditional owner communities. Negotiations should provide groups with a chance to identify the needs of their group and strategies to address these needs. The process of identifying need and developing strategies is a first and, crucial step in realizing economic, social and cultural rights.

Protection of culture

- NTA provides a limited protection of culture by recognizing some cultural practices and systems as native title rights and interests, eg Yanner.

- The future act process provides some protection of these rights from further impact.

- Protection under the NTA is limited - recognition of culture is based on 'frozen in time' view of Indigenous culture and societies; and provides for the recognition of only certain types of rights, eg no more than a right to control access to land.

- Agreement making provides opportunity for further protection of culture by: heritage protocols; support for group initiatives to strengthen culture; MoU's promoting traditional owner engagement with broader community and; cross cultural workshops for government and companies.

Self Determination

- Limited realization of self determination through NTA by:

- The registration of native title claims, future act and determination processes which provides a limited form of political status. PBC's provide a corporate structure for traditional owner political status.

- Ownership of land and resources is accommodated by the NTA through recognised or claimed native title rights and interests. However, ownership rarely extends to exclusive possession nor have the courts recognised ownership of mineral resources.

-

Social and economic development relies on meaningful exercise of self determination.

The right to development, capacity development and the Harvard project recognise the important link between social and economic development and self determination. Harvard in particular acknowledges that social and economic development cannot be achieved without stable and effective political status.

The opportunity for the establishment of a political structure through the native title process provides the foundation for social and economic development outcomes.

- However, the realization of self determination is undermined by the failure to recognise sovereignty (Yorta Yorta); strict limitations on rights; and failure to adequately fund the native title system (especially PBCs).

Equality

- Equality and non-discrimination are not protected within the NTA legal framework. The NTA disregards the operation of the Racial Discrimination Act to ensure that non-native title property interests are protected against native title rights. This legislative discrimination was criticized by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and the UN Human Rights Committee in 2000. Such discrimination weakens native title and undermines opportunities for development.

- This aspect of the NTA may be ameliorated by:

- Applying the non-extinguishment principle (occupation provisions s 44B - retrospective tenure disregarded)

- Extending property rights through other mechanisms, ie agreements, grants in land and legislation

- Working towards the equal distribution of benefits from development. External development projects must seek to extend opportunities from projects to local communities ie, employment, training, infrastructure access. This obligation is additional to the obligations of companies in compensation.

- Issues of equality should also be considered within native title groups in relation to the internal distribution of benefits within group. Proper governance structures should be implemented ensuring accountable, fair and transparent decisions. However, this approach should also be consistent with and subject to traditional law and custom.

Endnotes

- M Hemmati, Mult-stakeholder Processes for Governance and Sustainability, Beyond Deadlock and Conflict, Earthscan Publications Ltd, 2002

- Fukuda-Parr, Sakiko, Lopes, Carlos Malik, Khalid, Capacity for Development, New solutions to Old Problems, 2002, Earthscan Publications Ltd.

- Ah Mat, R., 'Excellence in Indigenous Governance and Accountability' in Institute of Public Administration Australia Conference 2003, Brisbane 28 November 2003.

- Cornell, S., 'Starting and Sustaining strong Indigenous Governance', paper presented at Building Effective Indigenous Governance, Jabiru,4-7 November 2003.

- United Nations, Report of the UN Inter-Agency Workshop on Capacity Development, Geneva 20-22 November 2002

- ATSIC Native Title and Land Rights Centre, Report of the NTRB Leaders Forum, Noosaville, November 2001, available at www.ntrb.net/images/userupload//pdf.report.pdf

- Altman, JC, 'Sustainable development options on Aboriginal land: The hybrid economy in the twenty-first century' CAEPR No. 226/2001; Dodson, M and Smith, DE, 'Governance for sustainable development: Strategic issues and principles for Indigenous Australian communities', No. 250/2003 CAEPR; Altman JC, and Whitehead, PJ, 'Caring for country and sustainable Indigenous development: Opportunities, constraints and innovation', CAEPR Working Paper No. 20/2003; Altman, JC and Finlayson, J., 'Aborigines, Tourism and Sustainable Development' in The Journal of Tourism Studies, Vol 14, No. 1 May 2003; Young, E., Third World in the First - Development and Indigenous Peoples, Routledge, London 1995

- Altman, J. and Finlayson, J., 'Aborigines, Tourism and Sustainable Development' in The Journal of Tourism Studies, Vol. 14, No. 1, May 2003

- Bernard Ominayak and the Lubicon Band v Canada, Decision of the Human Rights Committee, UN Doc. CCPR/C/38/167/1984 (1990)

- Human Rights Committee, General Comment 23 - The rights of minorities, (1994) para 7; in Compilation Of General Comments And General Recommendations Adopted By Human Rights Treaty Bodies, UN HRI/GEN/1/Rev.5, 26 April 2001, p147

- Resolution of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Yanomami Indians -v- Brazil, Case No 7615, resolution no 12/85, 5 March 1985 available at (accessed 15 September 2003)

Indigenous Communities Coordination Taskforce (ICCT), Shared Responsibility - Shared Future - Indigenous Whole of Government Initiative.