Native Title Report 2002: Summary of the Validation & Confirmation of Extinguishment Provisions in the NTA

Annexure

3: Summary of the Validation and Confirmation of Extinguishment Provisions

in the Native Title Act 1993

In the High Courts

formulation of native title in Mabo (No 2), [1]

delivered on 3 June 1992, it was made clear that in the past, governments

could validly grant interests in land that would extinguish native title.

These grants could be made without payment of compensation to native title

holders. [2] At least that was as far as the common

law was concerned. The Court did not need to consider the effect of the

Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cwlth) (RDA) on laws

and grants after the RDA came into force on 31 October 1975. Laws and

grants after that date may have been invalid if, for example, the grant

extinguished native title in a discriminatory way. The effect of invalidity

would have been quite dramatic: in some cases the holders of government-issued

titles would not own the land they thought they owned.

In theory, the Government

could have left these issues for the courts to decide on a case-by-case

basis or, at the other extreme, legislated for blanket validation of all

past government acts to do with land. The purpose of validation is to

correct the legal effect of invalidity by reversing it in legislation.

Another possible approach, although cumbersome and time-consuming, would

have been to list all the laws and grants of interests in land made prior

to the Mabo (No 2) decision, and explicitly validate them.

Instead, the Labor government of the day decided to focus on the potentially

invalid acts, defined in a general way, and leave any unresolved questions

about the effect of valid acts on native title to the courts to resolve.

The Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth) (NTA), gave effect

to this broad policy approach and came into force on 1 January 1994. At

a political level, this allowed the Government to calm anxiety about potentially

invalid grants, but not resolve all outstanding legal questions against

Indigenous interests. One of the critical outstanding legal questions

was whether any native title rights survived on pastoral leases that covered

approximately 40% of the Australian land mass. That question was resolved

in favour of Indigenous interests in the Wik decision, delivered

on 23 December 1996. [3] The High Court deciding that

the grant of a pastoral lease did not necessarily extinguish all native

title rights.

Following the Wik

decision, the new Liberal-National Party coalition government, extended

the validation provisions to the date of the Wik decision, arguing

that the original NTA had been passed on the mistaken assumption that

pastoral leases extinguished native title. [4] It also

added a fairly comprehensive codification of what past government actions

extinguish native title. [5] This new approach represented

a reversal of the policy of leaving most unresolved questions to the courts

to decide and, in effect, moved the government response closer to the

blanket validation approach.

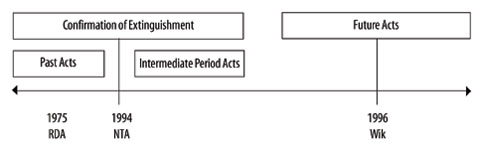

This history resulted

in the present complexity of the provisions in the NTA that try to address

historical legal uncertainties arising from Australias belated recognition

of native title. The provisions are organised into three divisions:

1 The Past Act

Validation Regime mainly dealing with invalid acts before the commencement

of the NTA on 1 January 1994; [6]2 The Intermediate

Period Act Validation Regime, mainly dealing with invalid acts between

the commencement of the NTA and the Wik decision on 23 December

1996; [7] and3 The Statutory

Extinguishment (Confirmation of Extinguishment) provisions dealing mainly

with valid acts prior to the Wik decision on 23 December 1996. [8]

Note: the word regime

is used to indicate that the validation provisions try to deal comprehensively

with the whole range of different government acts that might have different

effects on native title from non-extinguishment to partial extinguishment

to complete extinguishments. The Confirmation of Extinguishment provisions

focus exclusively on partial or complete extinguishment.

This could be represented

as follows: [9]

Figure

1: Validation Timeline

The significance of the Valid

/ Invalid Distinction and the RDA

Only invalid acts

are drawn into the validation regimes to be codified into non-extinguishing,

partially extinguishing or completely extinguishing acts. [10]

Although it is widely acknowledged that the only reason a government act

may have been invalid is a breach of the RDA, the RDA is not specifically

mentioned in any of the relevant definitions of past acts

or intermediate period acts. This is no doubt an example of

cautionary drafting just in case there is some other, yet to be formulated,

legal argument that would result in invalidity apart from the RDA. But,

for practical purposes, to find the scope of the validation regimes, breaches

of the RDA must be considered. [11]

The relevant provision

of the RDA states that if a particular race does not enjoy certain rights

because of a particular law, the RDA will override that law so that the

persons of the affected race will enjoy those rights to the extent that

other races enjoy them. [12] The wording of this key

provision has a number of consequences in relation to the extinguishment

of native title under a law. [13]

The first is that

laws that extinguish native title are not necessarily discriminatory if

other peoples property rights are also extinguished to the same extent.

It also means that some laws which have a discriminatory effect on native

title rights will not become invalid, but will simply be supplemented

by the RDA to bring them up to a non-discriminatory standard. An example

of this is a law that allows for the extinguishment of land titles but

only provides compensation for non-native title interests. The RDA has

the effect of adding a right of compensation for native title holders.

But the extinguishment of native title is still valid.

These conceptualisations

introduce some difficult questions for judges, for example how to choose

the most appropriate non-native title property rights for the purposes

of comparison with native title rights to see whether they have been treated

equally or not. It may also be difficult to distinguish between those

laws that can effectively be supplemented by the RDA to bring them up

to standard, and those laws that simply do not have the mechanisms within

them to make this kind of supplementation effective.

The clearest example

of a law that cannot be supplemented by the RDA to bring it up to non-discriminatory

standard, is a law that specifically targets native title rights and attempts

to extinguish them or alter them in some way. The Queensland Coast

Islands Declaratory Act 1985, which sought to outlaw native title

claims, [14] and the Western Australian Land (Titles

and Traditional Usage) Act 1993, which sought to replace native title

with traditional usage rights, are two examples of this. [15]

The end result of

these distinctions is that extinguishment of native title by legislation

or acts done under legislation do not necessarily lead to invalidity.

Further questions need to be asked and relevant comparisons need to be

made before invalidity can be conclusively established. Thus it is probably

true to say that the number of invalid acts is probably smaller than may

have been originally imagined.

How do Validated Acts Affect

Native Title?

Despite the uncertain

scope of invalid acts, the validation regimes provide a reasonably comprehensive

codification of what the legal effect of validation is on particular kinds

of acts. This codification was based on legal opinion at the time, usually

extrapolating from the reasoning of the Mabo (No 2) and Wik

decisions, but it was also based on negotiations between the various interested

parties during the political process leading to the original NTA and the

1998 amendments. From the perspective of the effect on native title, the

codification in the Past Act Validation Regime could be represented broadly

as follows:

| Examples | Relevant Definition in the NTA |

|

| Complete extinguishment [16] |

Freehold |

Category A

|

| Partial extinguishment [19] |

Other leases (not included above or below) |

Category B Past Act that is inconsistent with some but not all native title rights. [20] |

| Non-extinguishment [21] |

Mineral exploration and mining leases |

Category C Past Act [22] Category D Past Act [23] |

One curiosity in

this initial codification was the inclusion of pastoral leases in the

category of acts that completely extinguish native title. [24]

Subsequently, the High Court came to a different conclusion in the Wik

decision. This means that there is a technical anomaly in relation to

the survival of residual native title rights on pastoral leases. If the

pastoral lease was invalid because of native title, the validation process

extinguishes all native title. However, if the pastoral lease remains

valid despite native title, the residual native title rights survive.

This assessment in

1993 about pastoral leases was less beneficial to Indigenous interests

than the subsequent Wik decision. Other assessments have proven

to be more beneficial in the light of subsequent judicial decisions. One

is having a catch-all category (Category D) to which the non-extinguishment

principle applies. [25] This means that all those acts

which are not specifically identified in other categories will fall into

category D. The non-extinguishment principle preserves native title to

the maximum extent possible while allowing the exercise of competing rights

granted under statute. [26] The other beneficial aspect

is the list of exceptions to extinguishment. As would be expected, these

included land granted to Indigenous people under land rights and other

legislation designed to benefit Indigenous people. Another exception is

known as Crown to Crown grants, that is land transferred from

one arm of the government to another arm of the government, whether it

be another department or a separate statutory authority. [27]

Land in this category was dubbed fake freehold by Indigenous

interests who saw it as allowing governments to illegitimately extinguish

native title even though no third party interest would be affected.

So far, no distinction

has been made between past acts and intermediate period acts. While the

codification of extinguishing effects in the two regimes is broadly similar,

it should be noted that the scope of invalid acts subject to the intermediate

period acts regime is somewhat narrower than the past acts regime, and

there are some differences in the codification of extinguishing effects

that would be significant in a particular case. [28]

For example, the Intermediate Period Acts Validation Regime does not apply

to acts that took place on unallocated Crown land [29]

and, following Wik, it provides that non-exclusive pastoral leases

did not completely extinguish native title. [30]

An invalid act that

is validated under either of the two validation regimes, and as a consequence

completely or partially extinguishes native title, entitles the relevant

native title holders to compensation. [31] The principles

for calculating compensation vary. Depending on how the extinguishing

act is characterised, the principle could be just terms [32]

or equating the lost native title rights with freehold title [33]

or some other principle. [34]

Statutory Extinguishment of

Certain Valid Acts

As explained above,

the 1998 amendments to the NTA saw a move beyond concern with invalid

acts to the much bigger project of codifying the extinguishing effect

of most valid government acts prior to the Wik decision. The title

of the new provisions, confirmation of past extinguishment,

indicates a government intention not to legislate beyond existing legal

principles. Inevitably, however, the codification involved finely balanced

assessments and extrapolation from the few Court decisions then available,

principally Mabo (No 2), Wik and the Fejo [35]

decisions. This extrapolation from existing decisions became one of the

most contentious aspects of the 1998 amendments.

The Government apparently

adopted the view that the Wik decision had introduced a new distinction

into Australian law: a lease granted under a statute that did not grant

exclusive possession and, therefore, did not extinguish all native title

rights, as opposed to a lease granted under statute that did grant exclusive

possession and did extinguish all native title rights. Thus in the confirmation

of extinguishment provisions there is a broad distinction made between

previous exclusive possession acts and previous non-exclusive

possession acts. [36]

Some of the acts

included in the definition of previous exclusive possession acts

were consistent with existent legal authority such as the extinguishing

effect of a grant of a freehold estate (from the Fejo decision)

and the extinguishing effect of the construction of public works (from

the Mabo (No 2) decision). [37] Others

were drawn from the previous codification embodied in the past act validation

regime and included commercial leases, exclusive agricultural leases,

exclusive pastoral leases, and residential leases. [38]

But the list went

further. It included:

- an exhaustive

list of leases from all major States and Territories that were said

to grant exclusive possession. [39] The list was

compiled by negotiation between Commonwealth and State officials. None

had been subject to any judicial consideration of their effect on native

title. The government officials based their assessment principally on

an extrapolation from the Wik decision. - community purpose

leases; [40] - the vesting of

exclusive possession of land to a person under legislation, whether

exclusive possession is expressor implied; [41] and - a definition of

public work that extended the area of the public work to include any

adjacent area that was necessary or incidental to the construction of

the public work. [42]

As with the validation

regime, there are some important exceptions made to these extinguishing

acts, including beneficial land grants to indigenous people and the Crown

to Crown grants. [43] A further exclusion from

the definition of exclusive possession acts is areas established as parks

for the preservation of the natural environment. [44]

Compensation to native

title holders is limited to those cases where it could be demonstrated

that the native title rights involved would not have been extinguished

apart from the NTA, that is when assessments made in extrapolating from

the Wik decision prove to be incorrect. [45]

The second major

category in the confirmation of past extinguishment provisions, previous

non-exclusive possession acts, concerned those agricultural and

pastoral leases, like the lease in the Wik decision, that did not

grant exclusive possession. [46] These provisions appear

to be an attempt to codify the Wik decision. However, at the time

these provisions were formulated there was a major dispute between Indigenous

interests and the Commonwealth Government about the meaning of the Wik

decision. The government was convinced that, according to Wik,

native title rights that were inconsistent with the rights granted to

the pastoralists under the lease would have been permanently extinguished

leaving only some residual native title rights (the partial extinguishment

view). Indigenous interests argued that the question of permanent extinguishment

had not been resolved in Wik and that it was still open to view

the inconsistent native title rights as being merely suspended for the

duration of the pastoral lease (the suspension view). The final form of

the relevant provisions, negotiated between the Government and Senator

Harradine, seemed to suggest that this issue was left open for the courts

to decide in future cases. [47] But in the Miriuwung

Gajerrong decision the High Court seemed to interpret the provisions

as a codification of the partial extinguishment view. [48]

Thus, whatever the intention of the drafters of the relevant provisions,

the effect of a previous non-exclusive possession act is to

permanently extinguish inconsistent native title rights.

Accordingly, the

confirmation of extinguishment provisions could be summarised as follows:

| Examples | Relevant Definition in the NTA |

|

| Complete extinguishment [49] |

Leases |

Previous exclusive possession act [50] |

| Partial extinguishment [51] |

Non-exclusive |

Previous non-exclusive possession act [54] |

Implementation by States and

Territories

As outlined above,

it is difficult, if not impossible, for the States to pass legislation

effecting the extinguishment of native title without breaching the RDA.

Accordingly, they must rely upon the NTA, a Commonwealth Act passed after

the commencement of the RDA, to override the RDA. Both in relation to

the validation regimes and the confirmation of extinguishment provisions,

the NTA authorises the enactment of such legislation provided that it

is drafted to the same effect as the Commonwealth provisions. In relation

to validation and confirmation of extinguishment, the NTA makes a distinction

between acts attributable to the Commonwealth and acts attributable to

the States and Territories. [55] The provisions relating

to Commonwealth acts take effect immediately; however, the validation

of acts attributable to States and Territories and the confirmation of

the extinguishing effects of State and Territory acts is only effected

when particular States and Territories pass their own legislation in line

with the requirements set out in the NTA. Typically, these requirements

are that the key provisions are to the same effect as the provisions applicable

to Commonwealth acts. [56] Most States and Territories

have passed such legislation. [57]

Conclusion

The belated recognition

of native title rights in Australia means that most government acts affecting

native title have already taken place over the 200 years of colonial settlement

prior to the Mabo (No 2) decision. Initially, the Government

decided to focus on validating any invalid grants of land, but a subsequent

Government expanded this approach to include a codification of all those

government acts in the past that extinguished native title. This resulted

in a complex, difficult to summarise, set of provisions in the NTA specifying

the effect on native title of various past government acts. To find out

the effect of any particular act, a checklist of enquiries has to be made

to see which provisions of the NTA, if any, are engaged.

Assuming the relevant

subsidiary legislation has been enacted by the particular State or Territory

responsible for the act, the checklist of enquiries is as follows:

1 Did the act have

a racially discriminatory effect on native title rights?2 If so, is the

consequence that the act is invalid by virtue of the RDA?3 If it is an invalid

act, does it fall within the past act regime or the intermediate period

act regime?4 Under either

validation regime, is the act covered by any exception. If not, is it

a Category A, B, C or D act? This categorisation will indicate whether

the effect of the act on native title rights is to completely extinguish

them, partial extinguish them or not extinguish them.5 If the act is

not invalid, and is not covered by any relevant exception, does it fall

within the definition of a previous exclusive possession act

or previous non-exclusive possession act in the confirmation

of extinguishment provisions. The consequences are total extinguishment

or partial extinguishment respectively.6 If the act does

not fall within the validation regimes or the confirmation of extinguishment

provisions, the effect of the act on native title rights would have

to be decided by the courts on general principles.

This could be represented

as follows:

Figure

2: The scheme of the validation / statutory extinguishment regime

Further reading

Australian Government

Solicitor Commentary on the Native Title Act 1993, Canberra.

Richard Bartlett

Native Title in Australia, Butterworths, Sydney, 2000, chapters

13-17.

Commonwealth of Australia

Native Title Amendment Bill 1997 Explanatory Memorandum, parts

2 and 3.

The Laws of Australia

Volume 1 Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders; 1.3 Land Law; Chapter

3 Native Title Legislation, Part B; the Scheme of Native Title Legislation,

para. 95-117, Law Book Company, Sydney.

1

Mabo and ors v Queensland (No 2) (Mabo No 2)

(1992) 175 CLR 1.

2

Mabo (No 2), op.cit., per Mason CJ and McHugh J at 15.

3

Wik Peoples v Queensland & ors (1996) 187 CLR 1.

4

Native Title Amendment Bill 1997 Explanatory Memorandum, chapter

4; House of Representatives Second Reading Speech, 4 September 1997 at

p 7886-7888. Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth) (NTA), Part

2 Division 2A.

9

Note: for simplicity some past acts, like certain lease renewals,

that extend beyond 1994 have been omitted and likewise with intermediate

period acts: see ss228, 232A.. Also, some future acts

can occur on or after 1 July 1993: see s 233.

10

NTA, s228(2)(b) (in the definition of past act) and s232A(2)(c)

(in the definition of intermediate period act).

11

See for example discussion of this point in Western Australia v Ward

& ors [2002] HCA 28 (8 August 2002) (Miriuwung Gajerrong),

per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow & Hayne JJ at [98]-[135].

12

Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cwlth), s10(1).

13

Miriuwung Gajerrong, op.cit., per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow &

Hayne JJ at [104]-[134].

14

Mabo v Queensland (1988) 166 CLR 186. Also see discussion in Miriuwung

Gajerrong, op.cit., per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow & Hayne JJ

at [110]-[112].

15

Western Australia v The Commonwealth (1995) 183 CLR 373.

16

NTA, s15(1)(a) (c), s19(1).

18

ibid., ss15(1)(c), 228, 230.

20

ibid., ss15(1)(c), 228, 230.

24

ibid., s229(3)(a) and s248.

25

ibid., ss15(1)(d), 232, 238.

27

ibid., ss229(3)(d)(i), 230(d)(i).

28

See NTA s22B (the effect of validation of intermediate period acts on

native title) and s232A (the definition of intermediate period act).

30

ibid., ss22B, 232B(3)(c), 248A.

31

ibid., ss17, 18, 20, 22D, 22E, 22G.

32

ibid., ss18, 22E, 51(1) (2).

33

ibid., ss20, 22G, 51(3), 240 (the definition of the similar compensable

interest test). Note: strictly speaking the comparison is to ordinary

title which is defined in section 253 to include leased land in

the Australian Capital Territory and the Jervis Bay Territory where residential

blocks are typically leasehold interests.

35

Fejo v Northern Territory (1998) 195 CLR 96.

38

ibid., s23B(2)(c)(iii)-(v). Compare s229.

39

ibid., ss23B(2)(c)(i), 249C and Schedule 1.

43

ibid., ss23B(9) and 23B(9C).

47

For example, the relevant paragraph of s23G(1) states:

(b) to the extent that the Act involves the grant of rights

and interests that are inconsistent with native title rights and interests

in relation to the land or waters covered by the lease concerned: (i)

if, apart from this Act, the Act extinguishes native title rights and

interests the native title rights and interests are extinguished;

and (ii) in any other case the native title rights and interests

are suspended while the lease concerned, or the lease as renewed, re-made,

re-granted or extended, is in force....

48

Miriuwung Gajerrong, op.cit., per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow &

Hayne JJ at [4]-[13], [24], [41]-[45], [76], [190]-[195].

55

See NTA., ss19, 22F, 23E, 23I.

56

ibid., ss19, 22F, 23E, 23I.

57

See for example: Native Title Act 1994 (ACT); Native Title (New

South Wales) Act 1994 (NSW); Validation of Titles and Actions Act

1994 (NT); Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld); Native

Title (Queensland) State Provisions Act 1998 (Qld); Native Title

(South Australia) Act 1994 (SA); Native Title (Tasmania) Act 1994

(Tas); Land Titles Validation Act 1994 (Vic); Titles (Validation)

and Native Title (Effect of Past Acts) Act 1995 (WA).

19

March 2003.