Native Title Report 2000: Chapter 3: Native title and sea rights

Chapter 3: Native title and sea rights

One of the major

events of the period covered by this report was the handing down of the

decision by the full Federal Court in the Croker Island case (1)

on appeal from the decision of Justice Olney. (2)

It is the major test case on the recognition of native title sea rights

and represents the most authoritative statement of the law in Australia

at the present time. It was a split decision and this chapter analyses

the human rights implications of the different legal positions adopted

by the majority and the minority decisions of the court. At the time of

writing, the High Court had already granted special leave to appeal the

Federal Court's decision and a date for hearing had been set for hearing

on 6 February 2001. Thus, the question of the full recognition of native

title rights offshore by the common law of Australia has yet to be finally

determined. This chapter is a timely survey of the issues that will be

before the High Court.

The recognition that

both the common law and the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA) give to

Indigenous rights to sea is different from the recognition that they give

to Indigenous rights to land. This difference does not arise from Indigenous

traditions but is a product of Western imagining. The consequence of imposing

limitations onto the recognition of native title sea rights is that the

level of protection extended to them by the common law and the legislature

is insufficient to ensure that either the traditions or the rights themselves

can be fully enjoyed by Aboriginal people. In fact, the present legal

position is that all other interest groups competing for a commercial

or economic stake in the sea take priority over Indigenous rights. It

is this prioritising of non-Indigenous interests over Indigenous interests

that has attracted the criticism of international human rights committees

in the past 12 months. In this chapter I will analyse the trends in both

the common law and the legislation within a human rights framework in

an attempt to understand the basis of the recent international concern.

1. Overview of the variety

of indigenous traditions relating to sea country

Mary Yarmirr was

one of the main Indigenous witnesses in the hearing of the Croker Island

case. 'As far as my eyes can carry me' was her answer under cross-examination

to the question of the extent of her traditional sea country.(3)

It is just one of her answers that exemplifies the gulf between Indigenous

and non-Indigenous understandings of the coastal seas. When Indigenous

people like Mary Yarmirr assert their rights to 'sea country' it is a

challenge to the European imagination to conceive of traditional 'country'

in which there is no essential difference between the land and the sea

parts. The prime example of this unity of land and sea country is the

dreaming story. Typically, it is the sacred account of the creation of

the physical and social world by dreaming ancestors in their heroic and

ancient travels that are recounted in song cycles, ceremonies, designs

and ultimately the basis for claims to country according to traditional

laws and customs. The ancestral journeys often commence out at sea then

move closer to land, creating seascapes - islands, reefs, sandbars and

so on - and travel on to create landscapes. Thus the kinds of connections

that are widely documented in relation to land are also present in relation

to sea country. They include:(4)

- Multitudinous named places

in the sea including archipelagos, rocks, reefs, sand banks, cays, patches

of seagrass; - named zones of the sea

defined by water depth;(5) - bodies of water associated

with ancestral dreaming tracks; - sacred sites that are the

physical transformation of the dreaming ancestors themselves or a result

of their activities; - cloud formations associated

with particular ancestors; - sacred sites that can be

dangerous because the power of the dreaming ancestors is still there,

for example important places on reefs that can be used either to create

storms or make them abate;(6) - ceremonial body painting

and other painted designs using symbols of the sea such as the tail

of a whale, black rain clouds over white foaming waves, reefs, sandbanks,

islands, foam on the sea, a reef shelf;(7) - particular kin groupings

having a special relationship with tracks of the sea by virtue of their

inheritance of the sacred stories, songs, ceremonies and sacred objects

associated with it and by exercising control over that area.

The depth of these

cultural links to the sea is not surprising considering the antiquity

of the Indigenous engagement with the sea, particularly for the provision

of food over thousands of years. (8)

Indeed, the archaeological record indicates that on some islands off

the north Queensland coast the sea was more important to Indigenous survival

than the land.(9)

Indigenous people

from many parts of northern Australia have asserted the holistic nature

of their claims to the sea. They have also insisted that their sea country

does not belong to everyone, it belongs to particular Indigenous people.

They have explained the intricacies of their systems to anthropologists

who have documented them for numerous Indigenous peoples including the

Umpila-speaking people and other 'Sandbeach People' of Eastern Cape York,

Torres Strait Islanders, the Lardil, Yangkaal, Ganggalida and Kaiadilt

people in the Wellesley Island region of the Gulf of Carpentaria, the

Yanyuwa around the Sir Edward Pellew group of islands in the Gulf of Carpentaria,

the Anindiliyakwa of Groote Eylandt; Burarra and Yan-nhangu and Yolngu

of Arnhem land, and the Bardi and Yawuru people near Broome.(10)

Diversity

Much of the detailed

testimony about the intricacies of traditional sea rights comes from remote

areas where Indigenous peoples have been able to maintain fairly continuous

contact with their traditional sea country throughout the period of colonisation.

Such relatively uninterrupted association is not the case in most of Australia.

There are a variety of historical circumstances and contemporary cultural

traditions. The archaeologist Bryce Barker, for example, describes the

situation of the descendants of the traditional owners of the Whitsunday

Islands off the north coast of Queensland. (11)

The first substantial non-Indigenous intrusion into the area was in

1860 when Port Denison (Bowen) was established. Initial good relations

gave way to a brutal period of suppression involving the Queensland Native

Mounted Police following the attack and burning of the ship Louisa Maria.

In 1881 the remaining Island people gathered at Dent Island Lighthouse

for protection and were eventually moved to the mainland where all of

their descendants were born. Now traditional knowledge consists of stories

relating to marine species and knowledge of specific locations including

reef and mangrove systems as well as relating to the outer barrier reef

itself. The traditional owners are in dispute with the Great Barrier Reef

Marine Park Authority over the hunting of the now endangered turtle and

dugong.

Another circumstance,

as described by Scott Cane, (12)

is the situation of the Aboriginal people of the south coast of New

South Wales out of which arose the New South Wales Court of Appeal decision

in Mason v Triton. (13) The Aboriginal families

involved in this case defended a prosecution for illegal fishing on the

basis of traditional rights. They have an historical connection with the

general area of the south coast of New South Wales going back to the time

of first settlement. As to be expected, after such a long period of intense

colonisation, ancient laws and customs were represented by what Cane calls

'an attenuated core of language and mythology'. A continuous involvement

in fishing both for subsistence and small-scale trading is backed up by

substantial archaeological evidence of the same pre-contact activity.

Cane's account of contemporary culture also includes some intriguing evidence

of the ancestors of the defendants trading fish with the early white settlers

in the region. Fishing is still very important to the identity of Aboriginal

people on the south coast and a seafood feast is an important part of

contemporary cultural celebrations such as NAIDOC week.

Similarly, in relation

to the Tasmanian fisheries prosecution case of Dillon v Davies,

(14) no general system

of traditional laws and customs was asserted by the Indigenous defendant.

The customary practice of taking abalone, being a practice that could

be archaeologically traced back to the defendant's ancestors at the time

of the first white settlement of the area and the activity subject of

prosecution, was relied on to support an honest claim of right.

2. Relevant international

human rights standards

The picture that

emerges from these accounts of Indigenous law and culture is that while

the Indigenous relationship to sea country is diverse it also constitutes

a unique interest which has no equivalent in the non-Indigenous legal

system. Within a human rights framework, the recognition of native title

must ensure that this unique relationship is protected and capable of

full enjoyment by Indigenous people. Where the common law does not provide

an adequate level of protection, it is incumbent on the legislature to

ensure that Indigenous culture is fully protected by non-Indigenous law.

In particular, the principles of equality and self-determination underlie

the obligation of states to meet their international obligations in this

regard.

Equality

The international

legal principles of equality and non-discrimination require that Indigenous

culture be protected. In particular, they require states 'to recognise

and protect the rights of Indigenous people to own, develop, control and

use their communal lands, territories and resources'.(15)

The relationship that Indigenous people have to sea country is part of

their distinctive culture and must be protected in accordance with these

principles.

This approach is

often referred to as a 'substantive equality' approach. It acknowledges

that racially specific aspects of discrimination such as cultural difference,

socio-economic disadvantage and entrenched racism must be taken into account

in order to redress inequality in fact. Measures must be taken to protect

cultural differences and to redress disadvantage. This approach can be

contrasted with a formal equality approach that merely requires that everyone

be treated in an identical manner regardless of such differences.

Increasingly, domestic

jurisprudence is accepting the international law standard that requires

more than formal equality and recognises the distinctive cultural rights

arising from the unique and enduring relationship Indigenous people have

with both land and sea. (16)

Protection of culture

Article 27 of the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) protects

Indigenous rights. It provides:

Members of ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities shall

not be denied the right, in community with members of their group, to

enjoy their own culture, to profess and practise their own religion, or

to use their own language.

A series of decisions

by the Human Rights Committee (HRC) has emphasised the importance of protecting

Indigenous peoples' lands and resources in order to ensure their cultural

survival, (17) and governments' duties to

take positive steps towards that end. The relevance of the HRC decisions

lies in their recognition of the central role that economic and resource

activities play in the maintenance of the cultural rights protected by

Article 27.

At its 69th session,

the HRC expressed concern about whether Australia was meeting its obligations

with respect to the protection of Indigenous culture and economy under

Article 27 of ICCPR:

The Committee expresses its concern that securing continuation

and sustainability of traditional forms of economy of indigenous minorities

(hunting, fishing, and gathering), and protection of sites of religious

or cultural significance for such minorities, that must be protected under

Article 27, are not always a major factor in determining land use.(18)

The consideration

of the Indigenous claims to sea should be viewed in the context of international

obligation of the State to protect Indigenous culture.

Self-determination

The right of Indigenous

peoples to self-determination, as set out in the ICCPR and the International

Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), is a right

of Indigenous peoples to control their lands, territories and resources.

Without such control, self-determination is empty of content. Indeed,

Article 1(2) of both the ICCPR and ICESCR provide, inter alia,

that:

- All peoples have a right

of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine

their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and

cultural development. - All people may, for their

own ends, freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources. In no

case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence.

The Human Rights

Committee has explicitly linked ICCPR Article 1(2) with Indigenous control

over traditional land and resources, and explicitly applied it to Australia.

In its Concluding Observations in respect of Australia at its 69 th session

in July 2000, the HRC proposed that:

The State party [Australia] should take the necessary steps

in order to secure for the indigenous inhabitants a stronger role in decision-making

over their traditional lands and natural resources 9 Article 1, para 2.

(19)

The jurisprudence

of the Human Rights Committee, including recent examination of Australia's

performance, shows that the international human rights community expects

that Australia will implement its obligations to its Indigenous peoples

under the instruments in good faith.

Other international norms

International Labour Organisation

Convention (No. 169) Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent

Countries 1989 (20)

While the International

Labour Organisation Convention 169 (the ILO Convention) has not been ratified

by Australia, its significance lies in the fact that it is the only international

human rights treaty dealing specifically with Indigenous rights. The ILO

Convention provides evidence of developing international customary law

in respect of Indigenous rights, a law which clearly recognises Indigenous

rights to use and exercise control over the natural resources available

in their traditional territories. It is clear from the wording of the

Convention that the term 'territories' includes land and sea.

Article 13 (1) provides

that governments shall respect the special importance of Indigenous peoples'

relationship with their lands or territories, which they occupy or use,

and in particular the collective aspects of this relationship. Importantly,

the concept of Indigenous territories is deemed, in Article 13 (2), to

include 'the total environment of the areas which the peoples concerned

occupy or otherwise use'.

In respect of the

use of the term 'territories' in the ILO Convention, noted international

law commentator Howard Berman has made the following observation:

Increasingly, indigenous rights have been conceptualised legally

in terms of territorial rather than simply proprietary possession. Territoriality

best describes the complex interrelationship between indigenous peoples

and the land, waters, sea areas and sea ice, plants, animals and other

natural resources that in totality from the social, cultural, material

and deeply spiritual nexus of indigenous life.(21)

It is clear that

sea rights fall within the ILO Convention's concept of 'territories'.

Articles 14 and 15 provide a high level of protection of Indigenous rights

in respect of possession, use and management of such territories and the

resources they contain. Article 14(1) affirms that the rights of ownership

and possession over the lands and territories which they traditionally

occupy shall be recognised. Article 15 requires states to safeguard Indigenous

peoples' rights to the natural resources throughout their territories,

including their right 'to participate in the use, management and conservation'

of those resources. When these articles are read in conjunction with Article

6(2) of the ILO Convention,(22) they

provide a strong level of protection in international law of Indigenous

peoples' rights to possess, use and manage natural resources in their

traditional territories, including the requirement of Indigenous agreement

or consent to decisions about the development of resources in Indigenous

land and sea territories.

Principle 22 of the Rio

Declaration of the UN Conference on Environment and Development 1992

This principle recognises

the vital role of Indigenous communities in ensuring sustainable environmental

management and the need to protect Indigenous lands and resources.

The Convention on Biological

Diversity 1993

This convention was

ratified by Australia in 1993. Articles 8(j) and 10 provide a high level

of protection to Indigenous traditional practices in respect of the conservation

and sustainable use of biological diversity. Indigenous people in Australia

have consistently complained about the degradation of their marine resources

through, among other things, the unsustainable fishing practices of non-Indigenous

people. Indigenous peoples have a right, recognised in international legal

principles, to not only use their marine resources on a sustainable basis

but also to protect them for future generations by participating in management

regimes, exercising a right to negotiate over proposed developments and

developing agreements with other stakeholders.

International Whaling Convention

1946

This convention,

to which Australia is a party, recognises the right of Indigenous people

to use their marine resources. An exemption from prohibitions on taking

whales is provided under the Convention for Indigenous peoples, who can

take whales for traditional subsistence purposes. Indigenous subsistence

whaling rights are consistent with Article 1(2) of the ICCPR and ICESCR,

which provide that 'in no case may a people be derived of its own means

of subsistence'. The right in respect of whaling has mainly been asserted

by Inuit peoples. The Australian government has also supported the right.(23)

Through the work of a Technical Committee of the International Whaling

Convention, the exemption has been developed to recognise the importance

of Indigenous co-operation and participation in decision-making affecting

Indigenous subsistence economies, the resources on which they depend and

the importance of traditional social, cultural and spiritual values.(24)

Torres Strait Treaty with

Papua New Guinea 1978

The Torres Strait

Treaty, between Australia and Papua New Guinea, which was finalised in

1978 and came into force in 1985, recognises Indigenous sea rights. In

developing the treaty, Australia was concerned to recognise and preserve

the livelihood of the Indigenous peoples of the Torres Strait Islands.

The Treaty establishes a Torres Strait Protected Zone to 'protect the

traditional way of life and livelihood of the traditional inhabitants

including their traditional fishing and free movement'.

The treaty uses the

term 'traditional' in place of the term 'Indigenous' but the meaning of

'traditional' is interpreted in a liberal fashion, so that, for example,

the treaty permits the use of modern fishing methods provided these methods

are consistent with contemporary custom. However, it seems likely that

some of the international law understandings of the right of Indigenous

peoples informed the making of the Treaty text.(25)

Certainly, the treaty provides a degree of recognition and protection

of customary or traditional rights for Torres Strait Islander People.

The policy implication would appear to be that similar legal protection

should, as a matter of equity, be afforded to other coastal Indigenous

peoples with traditional affiliations with marine areas in Australia.

The rights of Indigenous

peoples to use, manage and control the resources of the marine environment

within their traditional territories are supported by international laws

and principles. These rights can extend to exclusive possession of sea

domains, based on prior occupation and use, consistent with the traditions

and laws of the Indigenous peoples concerned. Indigenous people are entitled

to protect their resources, including customary marine tenures, from one

generation to the next.

3. Common law recognition

of native title rights to the sea

International human

rights standards provide the relevant framework for the evaluation of

the common law approach to Indigenous rights in the Croker Island case.

There are few cases from overseas jurisdictions that have dealt with the

issues of native title sea rights so exhaustively as the Croker Island

case. The High Court's decision is therefore set to become an influential

precedent throughout the common law world.

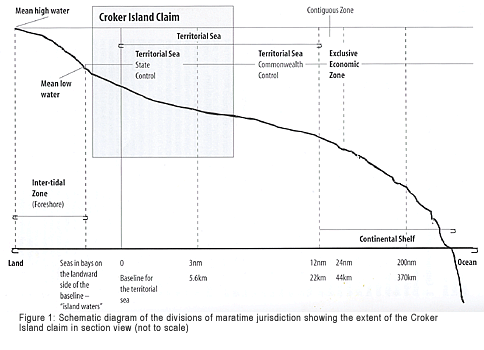

To understand the

territorial scope of the appeal to the High Court, the various maritime

jurisdictional limits imposed under Australian law on sea country need

to be briefly mentioned. They are set out in the sectional diagram in

Figure 1 [see next page].(26)

The Croker Island

claim does not include the foreshores/seabed in the intertidal zone, even

though this appears to have been the intention of the claimants. The entire

claim is within Australia's territorial sea and most of the claim falls

within the territorial sea in the jurisdiction of the Northern Territory.

The territorial sea is the maritime zone in which full jurisdiction is

asserted by Australia subject only to a customary international law requirement

of innocent passage.(27) The fact that the

claim is totally within the territorial seas means that the case does

not necessarily decide issues of native title in relation to the contiguous

zone, the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf. In relation

to these more distant zones, however, there is United States authority

to suggest that, even in these areas, Indigenous subsistence rights can

be recognised.(28)

Evidence in the Croker

Island case: a unique and complex system of laws

The claimants' evidence

in the hearings of the Croker Island case presented the sea as part of

an elaborate system of laws and customs that had been substantially maintained

to the present day. The details of that system were set out in the claimants'

evidence, the anthropologist's report (29)

and are summarised in Justice Olney's judgment.(30)

The claim was presented

in terms of the traditional rights of six 'estate groups' to five fairly

well-defined areas of land and sea. The estate group, like a 'clan', is

a single group of people who can trace their descent through the male

line and is known as a yuwurrumu. The yuwurrumu have names and those involved

in this claim were the Mangalara, Mandilarri-Ildugij, Murran, Gudura,

Minaga and Nganyjaharr. The traditional rights of the members of the yuwurrumu

included such things as:

- to be recognised as the

traditional owners of the estate, to transmit all inherited rights,

interests and duties to subsequent generations and to exclude or restrict

others from the entering the area; - to speak for and make decisions

about all aspects of the estate; - free access to the estate

and its every day resources in normal circumstances; - the right of senior members

to receive a portion of major catches (for example turtle, dugong, crocodile

or big hauls of fish) if they are co-resident with the person making

the catch; - the right of senior members

to close off areas of the estate on the death of yuwurrumu members and

decide when they shall be re-opened to use; - to allocate names associated

with their estate to their relatives; - to speak for and make decisions

about the significant places in the estate and to ensure unintended

harm is not caused by them or to them; - to receive, possess and

to safeguard the cultural and religious knowledge associated with the

estate and the right and duty to pass it on to the younger generation;

and - the right to speak for and

make decisions about the estate resources and the use of those resources

and the right and duty to safeguard them.(31)

The evidence presented

by the claimants, particularly the main witnesses, Mary Yarmirr and Charlie

Wardaga, included:

- accounts of the land and

sea creating travels of the dreaming ancestors - the Seahawk Burarrgbiny

Garrngy, Warramurrungunji, and to the named sacred sites associated

with the stories; - women's and men's ceremonies

associated with different dreaming sites; - the severe consequences

of revealing secret/sacred parts of stories and ceremonies; - accounts of inheritance

of rights through the claimants' fathers and being taught about the

country by fathers and grandfathers; - repeated assertions of

ownership and the right to be asked about developments such as petroleum

exploration, commercial fishing and tourism; - an example of permission

being given to establish a pearl farm; - examples of the closure

of certain areas following a death; - examples of seeking permission

to use another yuwurrumu area; - extensive accounts of fishing

and hunting for turtle and dugong at particular locations on the estates; - trade between the members

of different yuwurrumu, trade with the mission and trade with the Macassans

The Croker Island decision

Justice Olney accepted

that all of the claim area comprised the sea country of one or another

of the several claimant yuwurrumu, in other words, that native title existed

and that the claimants are the native title holders of the whole area.

The main difference between the claims and Justice Olney's findings was

the nature and extent of the rights recognised.

The NTA requires

the Federal Court, when making a native title determination, to state,

among other things, 'whether the native title rights and interests confer

possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the land or waters on its

holders to the exclusion of all others'.(32)

The claimants sought a determination that they did have such rights. Justice

Olney's proposed determination stated that they did not have such rights.

This was a crucial and much disputed finding and is discussed in more

detail below.

The NTA also requires

that the nature of native title rights determined to exist is set out

in the determination.(33) The claimants sought

an extensive list of rights based on the claimants' traditional rights

(set out above). Justice Olney accepted some of these but rejected or

curtailed others. The claim to a right of ownership was rejected, principally

on the basis that the terminology of 'ownership' was considered inappropriate

in the native title context because it did not necessarily equate with

any particular Indigenous concept. The claimed rights to control resources

was rejected. because of a lack of evidence of the use of the resources

of the soil under the seabed. The claim to a right to control access to

sea country was also rejected. The claimed right to trade was rejected

on the basis of insufficient evidence and insufficient connection with

native title sea rights. The generality of the claimed right to safeguard

cultural knowledge was reduced to cover only situations that required

presence on sea country.

The native title

determination of the court was as follows:

4. The native title rights

and interests which the Court considers to be of importance are the

rights of the common law holders, in accordance with and subject to

their traditional laws and customs to have free access to the sea and

seabed within the claim area for all or any of the following purposes:(a) to travel through all

or within the claimed area;(b) to fish and hunt for

the purpose of satisfying their personal, domestic or non-commercial

communal needs including the purpose of observing traditional, cultural,

ritual and spiritual laws and customs;(c) to visit and protect

places which are of cultural and spiritual importance;(d) to safeguard their cultural

and spiritual knowledge.

This determination

effectively reduces the rights that the claimants are able to exercise

in respect of their traditional sea country from being rights against

the whole world to rights that must either coexist with or be subjugated

by all other common law rights.

Justices Beaumont

and von Doussa in the majority of the full Federal Court decision in the

Croker Island case endorsed Justice Olney's finding that only non-exclusive

cultural and subsistence rights could be recognised by the court. There

are three bases to this decision:

- the court would not recognise

exclusive native title rights if they had not been exercised against

non-Indigenous trespassers; - the court's conceptualisation

of native title was limited; - the court found, as a matter

of law, exclusive native rights offshore would be inconsistent with

other common law rights of the public to navigate tidal waters and to

fish, and with the international law obligations to allow innocent passage

of shipping in territorial seas.

1. Non-recognition of exclusive

native title rights

The finding against

exclusive native title rights outlined above appears to be based on the

fact that the claimants did not enforce these rights against non-Indigenous

people. The connection between these two propositions is never fully explained

in the judgment. The relevant section commences with an extract from the

evidence of Charlie Wardaga:

Q. If we wanted

to travel on your water, by your law what should we do?A. I can't do nothing,

because you been talking about another balanda [whitefella] he coming

into you law boat, like that.Q. I am talking

your law?A. Yes.

Q. Aboriginal way?

A. Yes, my Aboriginal

law. That balanda he break that the Law, like that. Not like you mob,

you been come and see me - I'm clan, or Mary clan, like that. And other

people, oh, no, he got no brains that one.

Doing the best I

can, I understand the witness to be saying that a non-Aboriginal person,

who did not know of the traditional Aboriginal law and thus would be unaware

of the need to seek permission from the clan owner, should be allowed

to pass through.(34)

The claim that by their traditional laws and customs the applicants

enjoy exclusive possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the waters

of the claimed area is not one that is supported by the evidence. At its

highest the evidence suggests that as between themselves, the members

of each yuwurrumu recognise and defer to, the claims of the other yuwurrumus,

to the extent on occasions permission is sought before fishing, hunting

or gathering on another sea clan's country. By inference, although the

evidence is not strong, other Aboriginal people from outside the claimed

area probably do likewise.(35)

His Honour's reasoning

suggests that in order to establish a native title right to control access,

Aboriginal people would be required to demonstrate before a court not

only the existence of a traditional right to control access to their land

and the exercise of this right by the applicants, but also that the native

title applicants and their forebears, in the face of inordinate risks,

asserted this right consistently against non-Indigenous people through

the post-sovereignty period. While Indigenous people may continue to observe

their laws, under this test, previous non-Indigenous disrespect for their

rights provides a basis for the ongoing non-recognition and denial of

Indigenous rights.

The use of the applicants'

evidence of forbearance in the face of ignorance and disregard for their

laws as the basis of the denial of their right to control, is a new, more

onerous test for recognition of native title rights than was contemplated

in Mabo.(36) As Justice Merkel remarked in

the minority judgement of the full Federal Court:

It is important to emphasise that it is the traditional connection

with the land arising from the acknowledgement and observance of the laws

and customs by the community, and not recognition or acceptance by others

of the connection, or of the laws or the customs, that is the source of

native title.(37)

This approach is

also in stark contrast to the approach taken to proving exclusive possession

in the landmark Canadian case of Delgamuukw. (38)

Aboriginal title encompasses a right to exclusive possession, which

in turn is established if the following criteria are satisfied:

- the land must have been

occupied prior to sovereignty; - if present occupation

is relied on as proof of occupation pre-sovereignty, there must be a

continuity between present and pre-sovereignty occupation; and - at sovereignty,

that occupation must have been exclusive.(39)

Another context

in which to view Justice Olney's interpretation of the evidence is the

fact that there have been two Aboriginal Land Commissioner's reports on

sea closure applications under the Northern Territory Aboriginal Land

Act 1978,.Chapter 3 99 which were also in Arnhem Land.(40)

The significance of these reports is that rather than reporting on traditional

ownership per se, the Land Commissioner, among other things, must report

on whether, in accordance with Aboriginal tradition, strangers were restricted

in their right to enter the seas. In both cases, Justice Toohey and Justice

Kearney, respectively, found that strangers were so restricted and they

based their conclusions on evidence that is remarkably similar to the

evidence considered by Justice Olney. The Aboriginal Land Commissioners'

findings tend to support the impression that Justice Olney was taking

a very strict approach to the interpretation of the evidence in the Croker

Island case.

There are two approaches

to the task of ascertaining and recognising exclusive native title rights.

One is to focus on the exercise of excluding others, as Justice Olney

has done. The other is to make a global assessment of the completeness

of the traditional system of law and custom, taking into account all the

evidence of the traditional laws and customs and of continuing traditional

connection.

The former approach

anticipates a confrontation between the exercise of Indigenous and non-Indigenous

rights. An example of such a confrontation occurred recently when three

Torres Strait Islanders from Mer (Murray Island) found commercial fishermen

fishing in their traditional sea country.(41)

They confiscated the fish in the commercial fishermen's dinghies and

with the aid of a crayfish spear told the commercial fishermen in strong

terms to get out of the area. On their return to Mer Island, the Islanders

sold the confiscated fish and divided the proceeds amongst themselves.

Two of the men were charged with theft of fish with violence, an indictable

offence. So far, the charges have been successfully defended on the basis

of an honest claim of right based on the recognition of traditional fishing

rights under the Torres Strait Treaty. Although the defence is not based

on the exercise of native title fishing rights, these Torres Strait Islanders

are certainly laying the groundwork for a good claim under the test proposed

by Justice Olney.

The history of struggle

between Indigenous people for their land and sea country is littered with

confrontations of the type described above. Unlike the example given above,

many of these confrontations ended in the separation of Indigenous people

from their culture and their country. Consequently, many Indigenous people

are unable to sustain a claim for native title. Justice Olney's approach

to establishing exclusive native title rights ensures that even where

Indigenous peoples maintain connection to country, such as with the Croker

Island people, the common law will nevertheless limit the recognition

of the native title.

The latter approach

to ascertaining native title recognises that where Indigenous culture

has survived confrontation with non-Indigenous culture, then it should

be recognised in a way that ensures its enjoyment. Native title should

reflect the law and tradition of the claimant group as exercised and observed

by them. In this way, the common law will not only provide protection

for Indigenous culture so that it can be enjoyed within the broader community

but also allow the protective mechanisms existing within Indigenous culture,

such control of access to traditional country, to operate effectively.

2. The conceptualisation

of native title as a bundle of rights

Under the bundle

of rights approach native title is constructed as a highly specific and

finite series of practices derived from a particular historical moment.

There is little opportunity for Indigenous culture to continue to inform

the content of that bundle or for decisions to be taken about matters

outside of the defined bundle.

Where native title

is cast as a system of generalised rights, the exercise of those rights

can take a contemporary from even though their origin is the traditions

and customs of the original Indigenous inhabitants. Where, however, native

title is constructed as a collection of specific traditional practices,

there is a failure to separate the idea of rights from activities carried

out pursuant to those rights.

Justice Olney, and

the majority in the full Federal Court, construct native title as a bundle

of rights in which each separate native title right must be directly supported

by separate evidence of traditional laws and customs relating to the particular

right. This requirement and treatment of the evidence is consistent with

a bundle of rights approach to native title. In Chapter 2 of this report,

the bundle of rights approach to the legal characterisation of native

is criticised for predisposing native title to extinguishment. (42)

In the Croker Island case, it can be seen that the bundle of rights approach

also limits the extent to which Indigenous laws and culture will be recognised

at all by the common law, particularly where there is a claim for exclusive

rights. The bundle of rights approach limits common law recognition and

protection of Indigenous law and culture in three ways.

reduces the control that Indigenous people can exercise over country

The construction

of native title as a series of rights to perform specific enumerated practices

runs counter to its construction as an exclusive right to possession,

occupation, use and enjoyment of the territory. Only if the specific rights

proven add up to a difficult-to-specify comprehensive set of rights will

the exclusive right to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the

territory as against the whole world be determined to exist.

If this kind of determination

is made, the specification of what this entitles the native title holders

to do on the land is not that important. For example, in the Croker Island

case, if such a determination had been made, the specification of other

rights such as the right to use and control resources, the right to trade

and the right to protect places of importance would not have been crucial

because, in effect, they are all subsumed under the global right of exclusive

possession.(43)

Once it is decided

that an exclusive possession determination will not be made, the description

of the non-exclusive native title rights becomes extremely important,

for this description will define the totality of the rights. That is why

Justice Olney's failure to find a specific right to trade in the resources

of the estate was significant to the claimants. In the absence of a determination

of exclusive rights of possession, occupation, use and enjoyment, the

inclusion in the determination of a right to trade in resources was essential

to extend their acknowledged fishing rights beyond their own subsistence

needs.

Yet this discrete

right, like many others, was difficult to prove because of the nature

and extent of the evidence required. Even where evidence of contemporary

control over the claimed areas was provided, Justice Olney was reluctant

to interpret this as confirming exclusive rights. For instance, the applicants'

evidence that they insisted on being asked about important developments

in their country relating to oil exploration, tourism and commercial fishing,

was treated as supporting a right to be consulted and not as a right to

control access,(44) even though in traditional

Indigenous society asserting a right to be asked is a mode of asserting

exclusive rights to country.(45) In relation

to a right to trade, His Honour required detailed evidence of historical

and contemporary trading. Even this may not have been enough, as he indicates

that the exchange of goods may not be sufficiently related to land or

sea for it to be considered a native title right, notwithstanding that

the exchanged goods come from the land and sea.(46)

In the full Federal

Court, the majority agreed with Justice Olney's interpretation of the

evidence. Justice Merkel, although he was troubled by some of Justice

Olney's assessments of the evidence, did not have to decide the issue,

as he ultimately would have referred the matter back to Justice Olney

for reconsideration.

. The

bundle of rights approach fails to give Indigenous relationships to country

the protection afforded other non-Indigenous proprietary interests.

In Mabo, Justice

Brennan, with whom Chief Justice Mason and Justice McHugh agreed, famously

stated:

Native title has its origin in and is given its content by the

traditional laws acknowledged by and the traditional customs observed

by the indigenous inhabitants of a territory. The nature and incidents

of native title must be ascertained as a matter of fact by reference to

those laws and customs.(47)

In Chapter 2 of

this report, this separation of factual and legal elements of native title

is described as a critical ambiguity in native title doctrine.(48)

Indigenous law and custom are understood as the 'origin' of the right

that is not legally enforceable until it is 'recognised' by the common

law. Legal protection is thus dependant on a process of translation, and

only that which is 'translated' or recognised from Indigenous law will

be protected by the common law.

The courts' task

of cultural translation does not require that native title be constructed

as a title bearing no resemblance to a common law system of tenure. Nor

does it require that the court find exact equivalence between the common

law and Indigenous law and culture. The task for the court is to render

the unique relationship of Indigenous people to their country comprehensible

(recognisable) within the common law. What is significant from a human

rights perspective is that the form in which native title is recognised

by the common law gives Indigenous law and culture adequate protection

so that it can be fully enjoyed to the same extent as non-Indigenous interests.

If by likening native

title to a proprietary interest the common law provides the same level

of protection and security to the unique relationship that Indigenous

people have with their land and sea country as that which is provided

to all non-Indigenous proprietary interests, then such a translation is

consistent with the principle of substantive equality. Richard Bartlett

makes this point in his argument that, on the basis of equality, the common

law presumption against the extinguishment of a proprietary interest should

be extended to native title.(49)

The following statement

by Chief Justice Brennan in Mabo illustrates how the analogy to common

law proprietary interests is used to ensure that the protection of native

title is equal to the protection of non-Indigenous common law proprietary

interests:

If it be necessary to categorise an interest in land as proprietary

in order that it survive a change in sovereignty, the interest possessed

by a community that is in exclusive possession of land falls into that

category.(50)

In this statement

Chief Justice Brennan did not assert that native title is equivalent to

a 'proprietary' interest under the common law. Rather, that while the

Indigenous relationship with their country is entirely different from

common law 'proprietary' interests in the land, it requires an equivalent

degree of protection. It indicates that native title is to be regarded

as at least as strong a form of connection to land as common law proprietary

tenures and is equally protected by the common law.

Contrary to a human

rights approach, Justice Olney has interpreted Brennan's approach as authorising

a search for particular traditional laws and customs that demonstrate

the proprietary or non-proprietary nature of the rights claimed. The bundle

of rights approach justifies the fragmentation of native title into proprietary

or non-proprietary interests, each of which may be compared to common

law forms of property. This approach is not consistent with either the

authority in Mabo or a human rights approach.

fails to recognise the dynamic nature of Indigenous law and culture.

The bundle of rights

formulation denies the evolution of traditions to include contemporary

practices. For example, activities pursuant to native title rights are

restricted to pre-contract methods of exercising those rights (subsistence

fishing, not commercial fishing). On this basis Justice Olney summarily

dismisses the claimed right to the use of the resources (including minerals)

of the subsoil under the seabed. He states:

...as there is no evidence to suggest that any traditional law

or traditional custom of the Croker Island community relates to the acquisition

or use of, or to trading in, any minerals that may exist or be found on

or in the seabed or subsoil of the waters of the claimed area there can

be no basis for a determination that would recognise native title in such

minerals.(51)

While Justice Olney

is prepared to describe the determination area in the proposed draft determination

as including the seabed, the exclusion of the subsoil is based on a finding

that there is no close correspondence between ancient traditional activities

and contemporary potential mining uses.(52)

This is notwithstanding the evidence of the relationship of dreaming ancestors

to the seabed.(53)

Many of these problems

can be avoided if native title is conceived of as the ownership of territory

arising out of the exclusive occupation of the territory by Indigenous

people prior to the assertion of British sovereignty. There is authority

for this approach, most notably in the judgment of Justice Toohey in Mabo

(54) and in Delgamuukw.(55)

Proof of native title would still have its difficulties, as there would

be scope for wide variation in the level of evidence required to establish

exclusive possession at the time of sovereignty. However, it would avoid

the minute characterisation of particular traditional rights in order

to define the scope of current rights. Current native title rights would

equate with full ownership and questions about whether current activities

on the land were authorised by tradition would be irrelevant. This approach

maintains a definition of native title at a high level of generality,

distinguishing between the general right and its exercise at any particular

historical moment. Thus it provides a space for the survival of Indigenous

control over traditional land within the common law framework.

Under a substantive

equality approach native title should be a vehicle for the enjoyment and

protection of Indigenous culture, not a means to its confinement. Specifying

the practices which constitute native title while at the same time denying

the relationship that exists between these practices, confines the enjoyment

and protection of Indigenous culture within the common law.

3. Common law recognition

of exclusive native title rights offshore

The court's findings

jurisdiction

There is a threshold

legal issue of whether the common law extends beyond the low water mark.

If there is no common law offshore, the argument goes, native title cannot

be recognised. Justice Olney and the majority in the full Federal Court

seem to have accepted this proposition form the old English authority

of R v Keyn, (56) but their reasoning made

this question irrelevant.(57)

They held that native title could be recognised offshore since the

beginning of 1994 when the NTA commenced because the NTA itself, by virtue

of including a statutory definition of native title and by virtue of the

NTA's application offshore, revealed an intention to provide for recognition

of native title offshore. This is a neat solution because it also obviates

the need to distinguish between the various jurisdictional offshore zones

and the various times at which sovereignty in them was acquired. On the

other hand, it does put strain on the interpretation of the definition

of native title in the NTA by interpreting it as creating a kind of statutory

land rights.(58) It also causes some conceptual

difficulties, for under this theory native title could be extinguished

prior to 1994. This means that native title could be extinguished even

before it could have been recognised, post-1994.

The minority judge

in the Federal Court, Justice Merkel, opted for a different solution -

maintaining the significance of the date of assertion of sovereignty and

the relevance of recognition by common law by closely analysing the seemingly

problematic case of R v Keyn. He found that the High Court's apparent

endorsement of that case in the Sea and Submerged Lands Act case (59)

was really only an acknowledgement of the state of the law at the time

of Federation in 1901. Since then, there has been, in domestic Australian

law, a progressive extension of sovereignty further offshore. With that

extension of sovereignty comes jurisdiction and the operation of the common

law.(60) On this view, the question of the

relevant date for the proof of prior traditional laws and customs is resolved,

even if it is in a complicated way giving rise to four relevant dates

- 1824, 1863, 1930 and 1990 - corresponding with each extension of sovereignty

beyond land.(61) This would mean that the

relevant date for proving the prior occupation of the native title holders

would vary according to what part of the sea was being claimed.

Right to control access

Justice Olney and

all the members of the Federal Court found that the common law could not

recognise an exclusive native title right to control access because this

would conflict with the public right of navigation and Australia's international

obligation to permit innocent passage of ships through Australia's territorial

seas. Thus Justice Olney states:

The common law also recognises a public right of navigation

which has been described as a right to pass and repass over the water

and includes a right of anchorage, mooring and grounding where necessary

in the ordinary course of navigation; Hawsbury Laws of England (4 th ed,

1977), vol 18, par 604. This right evolved before Magna Carta and is therefore

a right distinct in its origin from the right of innocent passage in international

law. A native title right, such as the claimed right to exclusive possession

of, and to control the access of others to the claim area, would contradict

the public right of navigation and thereby fracture a skeletal principal

of a legal system. Such a right as claimed could not be recognised by

the common law.(62)

Justice Merkel also

agreed with this general proposition. He stated:

...the right claimed to exclusive possession of, and to control

access to, the claimed area fractures the skeletal principle of the freedom

of the seas and the tidal waters, which has given shape and consistency

from ancient times to the rights of innocent passage and to navigation.(63)

-

The exclusive right

to a fishery

The majority supported

Justice Olney's contention that the public right to fish and other rights

of navigation meant that the exclusive nature of native title fishing

rights could not be recognised. Justice Merkel, on the other hand, found

that an exclusive right to a fishery could exist and that they would not

necessarily be inconsistent with rights of navigation or a public right

to fish. He also hints that native title rights to regulate access to

sacred sites in a particular area may amount to exclusivity if they are

unlikely to significantly impede navigation.(64)

The significance

of Justice Merkel's findings go beyond the need for protection of Indigenous

marine resources. Since one of the main reasons for the intrusion of strangers

into sea country is to fish, an exclusive native title right to a fishery

may well give native title holders more influence over access generally.

Alternatives to non-recognition

Where a conflict

arises between Indigenous laws and customs and non-Indigenous laws a human

rights approach requires that they be given equal protection. In practice

this requires the court to seek to accommodate both sets of rights. There

are various ways in which such an accommodation could occur. Exclusive

native title rights in the territorial sea could be recognised and at

the same time be qualified by the international right of innocent passage.

This would give native

title holders some important rights of control, such as the right to exclude

domestic tourists and fishermen. There are many examples where the common

law recognises exclusive property rights that are nevertheless qualified

by the right of others to enter the land. The exclusive rights pertaining

to freehold title are not destroyed by the grant of a mining tenement,

but the title is nevertheless subject to the limitations imposed by the

grant of the tenement. The freeholder's rights remain good against the

whole world except one category of persons, namely those entitled to enter

under the mining tenement.(65) Similarly,

the native title holder's rights would be good against the whole world

except those who fall within the scope of 'innocent passage'.

Another means of

avoiding non-recognition of Indigenous law and culture is to consider

conflicting non-Indigenous rights as regulating Indigenous law. Just as

a right of international law to innocent passage does not undermine the

sovereignty of the coastal state over the territorial sea (66)

(nor its right to regulate the exercise of innocent passage in respect

of a number of matters),(67) nor should the

right of innocent passage prejudice Indigenous claims in the respect of

the use, management and control of their sea territories and resources.

International human

rights standards should be taken into account in the formulation of the

common law of native title offshore. It is one of the ironies of the development

of the law in this area that the often quoted passage from Justice Brennan's

judgment in Mabo) about the influence of international human rights law

on the development of the common law (quoted above), was also quoted by

Justice Olney in support of the proposition that the international obligation

to provide innocent passage justified the limitation of the recognition

of offshore native title to non-exclusive rights.(68)

The two international rules - the protection of Indigenous culture

and the right of innocent passage - can be accommodated together, in the

same way that the sovereignty of the coastal state and innocent passage

co-exist. Accordingly, it is not a necessary conclusion that the right

of innocent passage negates claims of exclusive native title rights to

customary marine tenures in Australian law.

If the common law

public right of navigation and fishing is inconsistent with exclusive

native title rights, as maintained by the majority, then the rule which

applies in relation to inconsistency between non-Indigenous interests

should also apply here; pre-existing proprietary rights should take precedence

over public rights that by their nature are not proprietary. This argument

is not new (69) and the legal authorities

supporting it are outlined in Justice Merkel's judgment in relation to

the exclusive fishery argument.(70).

Conclusion about the common

law

On the view of the

majority, the common law alone would not recognise any Indigenous rights

offshore. In their reasoning, it is only the NTA itself that extends the

possibility of the recognition of native title offshore. The limited rights

that can be recognised offshore only really address the issue of not depriving

a people of its own means of subsistence. Because the non-exclusive native

title sea rights must be shared with all others with public rights of

navigation and fishing, the common law position, as stated by the majority,

does not address the requirement of Indigenous control over Indigenous

resources, the requirement of informed consent before major decisions

are made, nor the acknowledgement of the role of Indigenous people in

ensuring sustainable environmental management.

4. Recognition of native title

rights to the sea under the Native Title Act 1993

Given the vulnerability

of the native title sea rights at common law, it is fitting and consistent

with the internationally recognised rights to enjoy one's culture that

native title should be provided particular protection by the legislature.

The legislative response falls short of its international obligations.

It adopts the same assumption that underlies the development of the common

law; it assumes there is a fundamental difference between Indigenous rights

on land and sea. As indicated, this assumption is not consistent with

an Indigenous perspective as incorporated in the ILO Convention that covers

'the total environment' of Indigenous people and the inclusion of sea

rights in the notion of Indigenous 'territories'. Nor is it consistent

with a human rights perspective, which seeks to protect Indigenous cultures,

their means of sustenance and their development.

There are four aspects

of the NTA that impact upon the human rights of Indigenous people and

their relationship to sea country.

Prioritising non-Indigenous

interests

Failure to extend the right

to negotiate to Indigenous interests in sea country

In both the original

and the amended NTA, the right to negotiate is limited to an 'onshore

place'.(71) The right to negotiate was seen

by Indigenous negotiators as extremely important to the overall acceptance

of the original NTA despite the validation of past acts. It is important

because, while not a veto, it sets a reasonable standard of protection

for Indigenous interests where exploration and mining is proposed on native

title land. The right supported genuine negotiation with Indigenous interests.

The practical significance of this relates mainly to offshore petroleum

exploration and extraction as there is little mineral exploration or mining

offshore. The decision not to extend the right to negotiate offshore has

denied Indigenous people the possibility of any meaningful negotiation

about future offshore petroleum developments. It has also denied them

a right to participate in the development and management of their country.

Validating offshore legislative

regimes

In the original NTA,

this objective was principally achieved by allowing the states to confirm

their existing ownership of natural resources, to confirm that existing

fishing rights would prevail over any other public or private fishing

rights and to confirm any existing public access to costal waters.(72)

All jurisdictions passed such legislation.(73)

The NTA provided

that such confirmation legislation does not have the effect of extinguishing

any native title rights.(74) Whether this

means that the native title rights are completely suppressed for the duration

of the confirmation or can coexist with the confirmed rights is difficult

to decide. Whatever view is correct, the existence of this legislation

presents a major hurdle to the recognition of full native title rights

offshore.

The 1998 amendments

took a different approach to the validity of offshore acts such as commercial

fishing and oil exploration. Rather than ensuring their validity by leaving

them out, the amendments explicitly validated them in the future act regime,

specifically in subdivision H (management of water and airspace) and subdivision

N (acts affecting offshore places) of the NTA.

Procedural rights

In the original

NTA, the procedural rights protecting offshore native title rights were

expressed in general terms. Native title holders received the same procedural

rights as anyone else with 'any corresponding rights and interests in

relation to the offshore place that are not native title rights and interests'.(75)

This contrasted with the statutory protection extended to onshore native

title rights, which were the same as those attached to freehold. In the

1998 amendments to the NTA, similar procedural rights were split between

subdivisions H, which covers waste management regimes and the granting

of such things as commercial fishing licences and subdivision N, which

covers everything else, typically, petroleum exploration of the seabed

and subsoil. Subdivision H specifies a right to be notified and an opportunity

to comment. The procedural rights in Subdivision N are in similar general

terms to the original NTA - the same rights as holders of ordinary (freehold)

title.

These procedural

rights are inadequate to protect the unique nature of Indigenous relationships

to sea and fall below international law standards of substantive equality.

In particular, they apply a formal equality standard to protect what are

unique Indigenous interests. Under this approach native title is given

the same procedural rights as non-Indigenous rights. However the measures

that are sufficient to protect a range of non-Indigenous interests will

not necessarily be adequate to protect native title interests.

The substantive equality

approach would recognise that Indigenous people in Australia have a special

relationship to sea country that requires special protection. The procedural

rights that are associated with native title rights to sea should not

be less than the procedural rights necessary to protect native title rights

to land.

There are other problems

with the protection offered to native title sea rights by statutory procedural

rights.(76) Two recent court cases demonstrate

some of the more technical shortcomings of these provisions.(77)

The Lardil case (78) demonstrates

that the wording of the procedural rights, which would indicate that they

are mandatory, is misleading. For example, the notification provisions

in subdivision H commence by stating 'Before an act covered by subsection

(2) is done, the person proposing to do the act must (a) notify.(etc)'.

But, if a state government does not offer the specified procedural rights,

a native title holder cannot readily insist upon them. Even if the native

title holders were already registered they would still have to present

evidence of their native title rights in order to obtain an injunction

to stop the act going ahead. In the meantime, if the act has been done,

it is valid notwithstanding the failure of the State government to provide

procedural rights. This loophole is a direct result of the fact that in

the amended and the original NTA the performance of procedural rights

is not a precondition for validity.

The second case,

Harris,(79) demonstrates that the procedural

rights specified in subdivision H are indeed as meagre as they appear

to be at face value and cannot be read as including any extra common law

procedural rights.(80) It also shows that

notice of acts, in this case issuing of licences to tourism operators,

can be given in such general terms that it is difficult to identify the

particular areas that will be affected by the activity. This seems to

be a direct and intended result of allowing the notification to relate

to acts 'or acts of that class'.(81)

The non-extinguishment principle:

s 44C

The non-extinguishment

principle is one of the major efforts in the NTA to protect native title

as it allows for the suppression of the exercise of native title rights

rather than their complete extinguishment by an inconsistent grant. The

non-extinguishment principle applies to acts that are valid under subdivision

H and subdivision N.

Generally speaking,

fisheries legislation has been seen as mere regulation of native title

rather than affecting any total or partial extinguishment. But the non-extinguishment

principle could be extremely important in preserving native title if the

theory of partial extinguishment, which was accepted by a majority in

the Federal Court in the Miriuwing Gajerrong case,(82)

becomes more widely applied. This theory is discussed in detail in Chapter

2.

The non-extinguishment

principle provides minimal protection to Indigenous rights. It is 'minimal'

because it accepts the complete inferiority of native title rights in

relation to the inconsistent non-Indigenous rights. Native title, while

not extinguished, is subjugated by the interests of non-Indigenous users.

Subsistence fishing rights

and traditional access rights: s 211

Section 211 provides

that Commonwealth, state or territory laws that are aimed at restricting

hunting and fishing etc without a licence, do not apply to certain activities

of native title holders undertaken in the exercise of their native title

rights. The activities include hunting, fishing, gathering and a cultural

or spiritual activity. There is a major limit on this exemption - the

purpose of the activity must be for satisfying personal, domestic or non-commercial

communal needs.(83)

The scope of the

laws to which the exemption applies was somewhat reduced in the 1998 amendments

to the NTA. The exemption does not now apply to a law that provides that

a licence is only to be granted for research, environmental protecting,

public health or public safety pruposes.(84)

What laws answer this description is not absolutely clear.

Given the prevalence

of statutory regulation of all sorts of fisheries, s 211 remains an extremely

important provision. It ensures that Australia complies with the international

human rights standard under both the ICCPR and the ICESCR, that in no

case may a people be deprived of its traditional means of subsistence.

Section 211 was, for example, the basis on which Murrandoo Yanner successfully

defended prosecution for the talking of crocodiles in the leading case

of Yanner v Eaton.(85) In that case, the

fact that Yanner was exercising his native title rights was not contested.

But in other cases, such as Dillon v Davies,(86)

the court has not accepted that the fishing question was an exercise of

particular rights according to traditional laws and customs.

5. The consequences of the

non-recognition of exclusive native title rights

In trying to assess

the practical consequences of the inadequate protection extended to Indigenous

sea rights by both the common law and the legislature, it is helpful to

identify the concerns that prompted the applicants in the Croker Island

case to lodge their claim. Some of them are mentioned in Justice Olney's

judgment: the increasing presence of non-Indigenous people, particularly

tourists and commercial fishermen, in the waters around the islands increasing

the risk of interference with offshore sacred sites, their ability to

harvest the resources of the sea, and their privacy,(87)

concern that these intrusions would limit Indigenous people's own capacity

for commercial development of the area; concern about the decline in the

most highly prized food resources of sea country - dugong and turtle.

A similar list of concerns motivated one of the sea closure applications

under the Northern Territory legislation.(88)

In the case of turtle, driftnet fishing by commercial fishermen is

suspected of being a major contributor. The decline of dugong is more

dramatic and difficult to understand. Overdevelopment of the foreshore

is one of the suspects. Indigenous aspirations in relation to their sea

country were extensively canvassed in the Resource Assessment Commission's

Coastal Zone Inquiry in the early 1990's (89)

and in other more recent reports. (90) As

will be seen, the various formulations of offshore native title rights

will have a direct bearing on the role which native title can play in

achieving these aspirations.

Non-exclusive rights

Even if native title

holders could convince a court of their exclusive native title rights,

the majority approach in the Croker Island case means that only non-exclusive

rights could be recognised offshore. The effect of this is that native

title rights are restricted to a right to travel throughout the area and

to hunt and fish. But native title holders would have to share the area

with the public by virtue of the public right of navigation and fishing.

They would not be able to exclude tourists or recreational fishermen.

The native title holders would not obtain any particular rights in relation

to the introduction of any new law for the management of the fisheries

in the area but they would have a right to be notified and to comment

on the grant of a commercial fishing licence. They would have to weigh

up whether exercising those procedural rights was worthwhile considering

the narrow scope for influencing the result. The rights of commercial

fishermen under their licence would prevail over all native title rights.

Subsistence native title fishing rights, however, would be exempted from

regulation by virtue of s 211 of the NTA.

There are difficult

questions of how the coexistence of statutory rights of commercial fishermen

and common law native title rights, protected under s 211, would operate

in practice. For example, if it were established that driftnet commercial

fishing was killing turtles as bycatch, could the native title holders

use their native title rights to force a change of fishing practices?

Consideration of how coexistence might work in relation to pastoral leases

may be found in the majority judgement of the full Federal Court decision

in Miriuwung Gajerrong. There, it was suggested that the law requires

that each set of coexisting rights must be exercised reasonably, having

regard to the interests of the other.(91)

But the extent to which such principles would apply offshore to restrain

commercial fishing is uncertain.

Without exclusive

native title rights, there is very little leverage for native title holders

to become involved in commercial fishing or other economic developments.

Their s 211 rights are specifically limited to non-commercial purposes.

Their common law rights mirror these limitations and begin to look much

the same as the common law rights of recreational fishermen.

Sacred site protection

would depend largely upon the effectiveness of state and territory Indigenous

heritage protection legislation and the extent of its application offshore.(92)

Overall, this position

responds to only one aspect of the relevant international human rights

standards - not depriving a people of their means of subsistence. Even

there the response may be inadequate, for a right to fish and to hunt

dugong and turtle will not be worth much if fish stocks are dwindling

and there are fewer and fewer dugong and turtle to be found. Obviously,

the future of subsistence fishing and the management of the environment

and the fisheries are interrelated. But the limitation of the recognition

of native title sea rights to non-exclusive rights relegates the native

title holders to being simply another interest group when major decisions

are being made about fisheries management, the granting of commercial

fishing licences, oil exploration, the management of marine parks and

so on. Yet it is these very decision-making activities and resource management

rights that are an integral part of relevant international human rights

standards.

Similarly, the right

to traditional access to the sea is a very minimal approach to the right

of minorities to enjoy their own culture and practice their own religion.(93)

It is the right to visit sacred sites but not to ensure their protection

by excluding others. It is the right to close seas to Indigenous people

after a death, but have that closure ignored by non-Indigenous tourists

and recreational fishermen.

Non-exclusive access rights,

possible exclusive native title fishery

The second situation

is the position of Justice Merkel, the minority judge in the Croker Island

case: non-exclusive rights of access combined with the possibility of

exclusive rights to a fishery and exclusive rights to sacred sites where

it does not unreasonably interfere with other navigation rights. As above,

the native title holders would not be able to control the access of non-Indigenous