4 Creating safe communities

- 4.1 Introduction

- 4.2 Justice reinvestment in Australia five years on

- 4.3 Justice targets

- 4.4 National Justice Coalition

- 4.5 Conclusion and recommendations

4.1 Introduction

The overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as both victims and offenders in the criminal justice system remains one of the most glaring disparities between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and non-Indigenous Australians. Indeed, in my view it is one of the most urgent human rights issues facing Australia.

I find it shocking that, as a society, we ‘do better at keeping Aboriginal people in prison than in school or university’.[409] The Aboriginal re-imprisonment rate (58% within 10 years) is actually higher than the Aboriginal school retention rate from Year 7 to Year 12 (46.5%).[410] Nationally, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults are 15 times more likely to be imprisoned than non-Indigenous Australians,[411] while around half of the young people in juvenile detention facilities are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander.[412] It is also simply unacceptable that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are hospitalised for family violence related assault at 31 times the rate of non-Indigenous women.[413]

The key to addressing the overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as both victims and offenders is safer communities. This means creating communities where violence is not tolerated and where victims have access to the entire spectrum of support services. It also means trying to prevent crime and violence from happening in the first place.

Throughout my term as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, I have made a priority of addressing this issue by advocating for justice reinvestment and justice targets. It is now five years since my predecessor, Dr Tom Calma AO, first called for justice reinvestment and justice targets for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.[414]

In particular, we have learnt a great deal about applications for justice reinvestment over the past five years. Justice reinvestment, once a radically new and unfamiliar idea, is now an influential part of criminal justice reform discourse in Australia.

This chapter will report on developments towards justice reinvestment in Australia, including ground-breaking community initiatives in Bourke and Cowra. It will also highlight some of the challenges for implementing justice reinvestment based on both the Australian context and international experience.

The concept of justice targets has also garnered significant interest, although unfortunately this has not yet resulted in government action. This chapter will extend the case for justice targets by presenting a range of options for developing and tracking targets.

The lack of concerted government action on justice issues has frustrated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, as well as others involved in the criminal justice sector. This frustration and determination to challenge inaction has been the catalyst for a newly formed National Justice Coalition, comprising of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous peak bodies and leaders in the area of criminal justice and victim support. This chapter will report on the development of the National Justice Coalition and its priorities. Just as the Close the Gap Campaign for Indigenous health equality has gained broad-based support and government action, I am optimistic that the National Justice Coalition can be a similar circuit breaker in advocating for safer communities.

4.2 Justice reinvestment in Australia five years on

In the past five years, it has been encouraging to see so many different people and groups embrace justice reinvestment. However, in all of this enthusiasm we have seen some confusion around what justice reinvestment actually involves. Some academics have warned of the potential pitfalls if justice reinvestment becomes a:

catch-all buzz word to cover a range of post release, rehabilitative, restorative justice and other policies and programs and thus lose both any sense of internal coherence and the key characteristic that it involves a redirection of resources.[415]

In my view, it is not necessarily detrimental that advocates in Australia are already trying to adapt justice reinvestment for the Australian context. What works in the United States can be a powerful catalyst for action, but will require thoughtful adaptation to the Australian context. Nonetheless, if the Australian brand of justice reinvestment strays too far from the evidence we may lose some of the strength of this approach.

There is now a growing body of literature on justice reinvestment,[416] so this chapter will only briefly summarise some of the key principles and processes of justice reinvestment to provide clarity and context.

(a) Justice reinvestment explained

Justice reinvestment is a powerful crime prevention strategy that can help create safer communities by investing in evidence based prevention and treatment programs. Justice reinvestment looks beyond offenders to the needs of victims and communities.

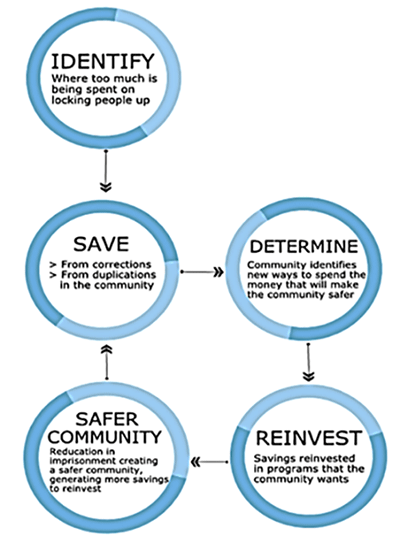

Justice reinvestment diverts a portion of the funds for imprisonment to local communities where there is a high concentration of offenders. The money that would have been spent on imprisonment is reinvested into services that address the underlying causes of crime in these communities. Figure 4.1 illustrates the primary process of justice reinvestment.

Figure 4.1: Justice reinvestment

Text version of chart:

Identify

Where too much is being spent on locking people up

Save

From corrections

From duplications in the community

Determine

Community identifies new ways to spend the money that will make the community safer

Safer Community

Reduction in imprisonment creating a safer community, generating more savings to reinvest

Reinvest

Savings reinvested in programs that the community wants

Justice reinvestment was developed in the United States by George Soros’ Open Society Foundation. There are currently 30 states in the United States pursuing justice reinvestment at the state level, and at least 18 counties in six states undertaking justice reinvestment at the local level.[417]

While justice reinvestment approaches vary depending on the needs of communities, justice reinvestment does have a consistent methodology around analysis and mapping. This work is the basis for the justice reinvestment plan.[418] Justice reinvestment approaches also require commitment to localism and budgetary devolution[419] and are only made possible through political bipartisan support.[420]

The success of justice reinvestment in the United States has been well documented.[421] Moves to justice reinvestment are also underway in the United Kingdom.[422]

(b) Developments towards justice reinvestment

Since 2009, justice reinvestment has been the subject of significant community advocacy. There are organised campaigns for justice reinvestment under way at the national level, as well as in New South Wales, Victoria, Western Australia, South Australia, the Northern Territory, Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory.[423] Supporters include grass roots community members, service providers, academics, lawyers, Police and judges.

Importantly, we have also seen support from victims’ groups. Prominent victims’ advocate Ken Marslew, has made supportive comments about justice reinvestment in the media:

Some people see it as a soft option, when in fact it is a very powerful tool. Some would be a little reluctant to see offenders have more money spent on them, but if we’re going to look at the big picture we really need to develop justice reinvestment across our communities.[424]

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander victims’ groups have also supported justice reinvestment.[425]

This wave of community support has been instrumental in placing justice reinvestment onto the political agenda. Justice reinvestment has been considered in at least six government inquiries in the past five years. In particular, the 2013 Senate Inquiry into the Value of a justice reinvestment approach to criminal justice in Australia received over 130 submissions.[426] Table 4.1 contains a summary of all of these inquiries and their recommendations.

Table 4.1: Government inquiries into justice reinvestment

|

Inquiry

|

Recommendations

|

|

Parliament of Australia, Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee:

Value of a justice reinvestment approach to criminal justice in Australia[427] (2013)

|

|

|

Parliament of Australia, House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs:

Doing Time –Time for Doing Report[429]

(2011)

|

|

|

Parliament of Western Australia, Community Development and Justice Standing Committee:

Making our prisons work[431]

(2010)

|

|

|

Parliament of New South Wales, Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee:

Access to Justice[432]

(2009)

|

|

|

New South Wales Minister for Juvenile Justice, Strategic Review of the New South Wales Juvenile Justice System:

Juvenile Justice Review Report[433]

(2010)

|

|

To date, the thinking around justice reinvestment in Australia has mainly been in relation to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. There are persuasive arguments for trialling this approach in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander contexts given the high levels of overrepresentation and disadvantage faced by these communities. The principles of a justice reinvestment approach include localism, community control and better cooperation between local services. These also align with what we know about human rights-based practice in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander service delivery.

Beyond these reasons, the reality is that if we were to map the locations with the highest concentrations of offenders, many of these locations would have very high numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders living in them.[434]

(c) Community justice reinvestment initiatives

Governments have not yet adopted justice reinvestment in Australia. However, at the community level, we are seeing some very exciting work about what justice reinvestment could look like in Australia. This section will provide case studies for the Bourke Justice Reinvestment Project that I have been involved in, and for an innovative community research project in Cowra.

(i) Bourke Justice Reinvestment Project

Bourke is a small remote town in far western New South Wales with a population of nearly 3,000 people. 30% are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.[435] Like many similar communities, Bourke has a young population, high levels of unemployment and disengagement from education, and high imprisonment rates. Text Box 4.1 provides more detailed demographic information.

Text Box 4.1: Snapshot of the Bourke Aboriginal community

Bourke is within the traditional lands of the Ngemba peoples - occupying the east bank of the Darling River around Bourke and Brewarrina. A recent mapping exercise identified the presence of Aboriginal people from over 20 language groups. The traditional owners, the Ngemba, are a minority alongside other major language groups including the Wanggamurra, Murrawari and Barkindji.[436]

There is a marked gap between the life experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous residents. For instance:

- in 2011, the median income of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults living in Bourke was approximately $416 per week, which was 39% less than the median income for all adults ($678).[437]

- 17% of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce were unemployed, compared with 2% of the non-Indigenous workforce in Bourke.[438]

- compared with non-Indigenous residents of Bourke of the same age, there were:

- 31% fewer Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander 15–19 year olds in education

- 7% fewer Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander 5–14 year olds in education.[439]

Bourke faces significant challenges in relation to community safety. According to the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) the Bourke Local Government Area has consistently ranked highest in the state for the rate of recorded incidents of domestic violence, sexual assault and breach of bail in recent years.[440]

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data in 2011 shows that out of a total 223 Aboriginal young people/young adults in the Bourke Local Government Area, almost a quarter (21%) were on remand or sentenced. This does not include others in contact with the criminal justice system, for instance, those charged and on bail, or those on non-custodial orders. Crimes identified with youth include:

- car related crimes (car theft, stealing from cars and breaking windows)

- breach of bail

- property crimes (criminal trespass, break and enter and malicious damage).[441]

At the same time, service mapping shows there are over 50 community organisations servicing the area and 40 Police. The problems of service integration have been well documented by the New South Wales Ombudsman.[442]

In February 2013, Bourke was the subject of the dubious headline, ‘Bourke tops the list: more dangerous than any country in the world’.[443] While this media reporting lacked nuance and sensationalised issues in the community, there is no denying the depth of challenges that need to be addressed to create a safer community in Bourke.

The Aboriginal community leadership in Bourke has courageously stepped up to take on the challenge of creating a safer community. The Bourke Aboriginal Community Working Party (BACWP), led by Mr Alistair Ferguson, approached Just Reinvest NSW in October 2012. They told the organisation that they had been working over many years to build the capacity of the Aboriginal community. Based on this work, they felt ready to trial justice reinvestment to try and break the intergenerational cycle of offending and incarceration.

One of Bourke’s strengths is the established local governance structure. Since 2002, the BACWP has been the peak representative organisation for the local Aboriginal community. The BACWP includes community members and representatives from 18 different organisations and receives funding from the New South Wales Government.

The Bourke Aboriginal leadership has also developed a comprehensive agenda for change. The strategy and structure is called Maranguka, a word from the language of the Ngemba Nation which, when translated into English, carries the meanings of ‘to give to the people’, ‘caring’ and ‘offering help’. The first priority of Maranguka is to reduce Aboriginal contact with the criminal justice system.

I have visited Bourke four times since 2013 to undertake community consultations. I have been impressed with the significant community commitment to face these issues in an inclusive way for change.

The National Children’s Commissioner, Megan Mitchell, has also been involved with these community consultations. I believe involvement from the National Children’s Commissioner has helped to enable the young people to have a voice in this process. There was a watershed moment at the end of our community meeting in October 2013, when one of the Elders said that this was the first time she had seen the young people take part in a meeting like this, and how proud she was of them. You could see those young people sitting up straighter and feeling really valued and heard. This foundation of respect and inclusion will help broad community ownership of any justice reinvestment plan.

As the project has evolved, the concept of ‘collective impact’ has come to inform the methodology for a justice reinvestment plan in Bourke. Text Box 4.2 provides a summary of collective impact.

Text Box 4.2: Collective impact explained

Collective impact can be summarised as diverse organisations from different sectors committing to a common agenda to solve a complex social problem. Collective impact is based on the premise that no single individual or organisation can create large-scale, lasting social change in isolation, and acknowledges that systematic social problems may only be solved by the coming together of organisations and programs.

There are five key elements underlying the collective impact model:

- a common agenda for change, including a shared understanding of the problem and joint approach

- shared measurement for alignment and accountability

- mutually reinforcing activities, whereby differentiated approaches are coordinated through a joint plan of action

- continuous communication focusing on building trust, and a backbone of support including the resources, skills and staff to convene

- the coordination of participating organisations.[444]

Collective impact initiatives that have been employed around the world to address various social issues have shown substantive results. Some initiatives targeting complex social problems include those relating to education, healthcare, homelessness, the environment and community development.

Collective impact has synergies with community development and may translate the more conceptual elements of justice reinvestment to a practical level.

With the community support established, the BACWP, Just Reinvest NSW and the Australian Human Rights Commission developed a project proposal. In August 2013, this proposal was distributed to philanthropic, corporate and government sectors, and the Australian Human Rights Commission hosted an engagement meeting with funders and stakeholders.

This approach has been successful in establishing funding and in-kind support to commence the justice reinvestment project. Starting in March 2014, for a two-year period, a consortium of partners will work with, and alongside, the Bourke community to develop a watertight social and economic case for justice reinvestment to be implemented in Bourke. The Bourke Community, the champions and supporters of Just Reinvest NSW and others will then take that compelling case for change to the New South Wales Government for response and action.

The Bourke Justice Reinvestment team now has the financial support and resources required to pursue this work. The team comprises of:

- Executive Officer: Alistair Ferguson is the Executive Officer in Community Development, and will be based in Bourke over the two-year project period. The position of Executive Officer is funded by the Vincent Fairfax Family Foundation and the Dusseldorp Skills Forum.

- Facilitator: Lend Lease is releasing Cath Brokenborough, Chair of Indigenous Engagement and Reconciliation, to fill the role of External Facilitator, and to be based in Bourke for three days per month.

- Data Manager: Aboriginal Affairs NSW has agreed to provide an in-house Data Manager to coordinate the collection and collation of data on Bourke.

- Data Reference Group: A Data Reference Group has been established, and includes representatives from the University of New South Wales (UNSW), the ABS and BOCSAR. Both the ABS and BOCSAR are providing data for this project. Aboriginal Affairs NSW will assist the Data Reference Group by conducting data relevant research for this project. As the project’s university partner, UNSW will further provide advice on best practice responses to achieve the agreed shared measures.

- Economic Modelling Team: Over the next two years, KPMG will lead the work of costing the implementation of justice reinvestment in Bourke. KPMG will also produce an economic modelling of the cost savings for government observers.

- Project Coordinator: The project will be coordinated by Sarah Hopkins, Chair of Just Reinvest NSW.

- Collective Impact Consultant: Kerry Graham will provide advice on the collective impact framework.

- New South Wales Police support: Sergeant Mick Williams, a respected Aboriginal Police Officer and recipient of the Australian Police Medal, has been assigned to support the project and Maranguka more broadly.

- Project Officer: St Vincent De Paul has funded a Project Officer to assist Alistair Ferguson for a 12 month term.

The project team has engaged with a range of stakeholders in the community and is currently working with the Courts, Police and other community stakeholders to develop a number of initial circuit breakers. Proposals include an amnesty on warrants for young people in Bourke, and a set of protocols relating to the imposition of bail conditions and the circumstances in which bail will be breached by the Police. The initial focus of this collaborative work will lead to a dialogue on a variety of underlying issues that impact on imprisonment, such as housing, employment and education.

Why is the Bourke Justice Reinvestment Project different?

The Bourke Justice Reinvestment Project is an innovative example of communities taking control for positive change. So far, I have identified two key differences in the process.

Firstly, this project is not just about creating a community plan. In my many years in Indigenous Affairs, I have seen numerous community plans, often initiated by government. Despite good intentions, many of these plans languished because there was too much emphasis on the creation of the plan, and not enough on building the relationships and commonalities of the stakeholders. Actions always speak louder than words. Or in this case, actions and relationships speak louder than plans.

In the Bourke Justice Reinvestment Project, we are seeing this process reversed. It is no accident that we spent such a significant period of time building relationships and expectations before we commenced the project. This goodwill is allowing us to find common ground and shared goals, for instance, around the initial circuit breaker proposals. Developing from our projects, relationships and learning, will be a justice reinvestment plan. The crucial difference will be that it will be built on achievements, not just aspirations.

Secondly, the funding consortium for the Bourke Justice Reinvestment Project is different. While the government is providing support to the project, the major funding and pro bono services come from philanthropic and corporate sources. Government funding requirements can be complex and cumbersome to manage, while corporates and philanthropists recognise and reward innovation. Corporates and philanthropists can also be nimble enough to provide resources more quickly and flexibly. This approach gives the Bourke Justice Reinvestment Project the correct degree of support and flexibility over the next two years.

(ii) Cowra Justice Reinvestment Project

Researchers from the Australian National University, led by Dr Jill Guthrie, are conducting an exploratory study in Cowra to evaluate the theory, methodology and potential use of a justice reinvestment approach to addressing crime, and particularly the imprisonment of the town’s young people.

Cowra is located in the central west region of New South Wales and has a population of 10,000 residents.[445] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples make up 6.5% of the population.[446] While Cowra has not received the high level of attention for justice issues that Bourke has, Cowra has been described as an ‘ideal case study site’[447] due to its stable population and middle range crime profile. Further to this, there is no direct economic benefit drawn from having a prison in the community. Although the impact of incarceration is far greater for Australian Indigenous populations, the study will focus on issues of incarceration of all young people from Cowra.

Dr Jill Guthrie explains the focus of the research:

This study is a conversation with the town to explore what are the conditions, the understandings, the agreements that would need to be in place in order to return those juveniles who are incarcerated in detention centres away from the town, back to the town, and to keep those juveniles who are at risk of incarceration from coming into contact with the criminal justice system.[448]

Participation in the project by the Cowra community has enabled the team to identify issues underlying the incarceration of its young people. Specifically, community groups and organisations have been consulted throughout the project to assist in identifying effective alternatives to prison which ought to be invested in, such as holistic and long-term initiatives, and better integrated services. Young people will also be interviewed about their experiences and suggestions for change.

The project will continue until March 2016, having commenced in April 2013. The project’s outcomes may lead to recommendations for addressing the levels of young people coming into contact with the criminal justice system. Similar to the Bourke Justice Reinvestment Project, the Cowra research will build an evidence base for justice reinvestment that may be used for future advocacy.

(d) Challenges

Five years on, it is worth considering some of the challenges that lay ahead in adapting justice reinvestment for the Australian context, about how we move from the speculative to the practical and how we can learn from the international experiences.

(i) Learning from the United States

The United States is now nearly ten years down the track with justice reinvestment. Even in the five years since justice reinvestment was first introduced in Australia, the concept has evolved in the United States and there is now a growing body of evidence and analysis.

Australian researchers have also been applying a critical lens to the way justice reinvestment has developed in the United States, in the context of Australian adaptations. Text Box 4.3 provides a summary of the preliminary findings of this research project.

Text Box 4.3: Australian Justice Reinvestment Project

The Australian Justice Reinvestment Project (AJR Project) is a two year Australian Research Council funded project which draws together senior researchers across the disciplines of law and criminology, to examine justice reinvestment in other countries, and to analyse whether such programs can be developed in Australia. Researchers recently visited six states (Texas, Rhode Island, North Carolina, Hawaii, South Dakota and New York) to examine implementation.

Based on this preliminary research, the AJR Project has identified six preconditions for implementing successful justice reinvestment reform:

- bipartisanship

- strong leadership

- early identification of the right people to engage as stakeholders

- substantial buy in from all sectors

- ongoing commitment to implementation at the reinvestment phase

- effective community engagement.[449]

Researchers noted that ‘justice reinvestment has come to mean different things in different contexts’,[450] with a mix of initiatives affiliated with the government funded Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI) of the Bureau of Justice Assistance, as well as newer local level initiatives.

At the state level, JRI:

tends to emphasise the passage of legislation enshrining general criminal justice reform and ... typically this is no place-based component and as such, the ‘reinvestment in high-stakes’ communities contemplated in the original vision of justice reinvestment is largely absent. Local level initiatives were more likely to take up a particular issue (eg housing for people involved with the criminal justice system).[451]

Researchers note that ‘worthwhile criminal justice reform is occurring under the justice reinvestment banner’[452] although it might be different to the original concept.

When we apply some of the research reflections to the development of justice reinvestment in Australia, what strikes me is that the community driven approach of justice reinvestment that we are seeing in Bourke is in fact closer to the pure principles of justice reinvestment than some of the initiatives that have emerged in the United States.

Despite the promise of a place-based approach with strong community engagement, the United States experience has become more focused on state-wide criminal justice reforms and investment into community corrections, such as probation and parole services. That is not to discount this approach or the reductions in imprisonment that have been achieved. However, to me at least, the real underlying power of justice reinvestment has always been in the place-based approach of community involvement and capacity building to create safer communities. In this respect, I believe we are on the right track in Australia.

The current lack of government initiatives in justice reinvestment in Australia may even be a blessing in disguise, as it gives the community the time to set up robust governance, sustainable systems and a ‘watertight case’ for justice reinvestment. With this in place, justice reinvestment will be on community, not government, terms.

Community governance, capacity and involvement are crucial in developing justice reinvestment plans with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Without these necessary elements, there is a risk that justice reinvestment will become yet another well-meaning plan that is rolled out by government but ultimately makes little difference.

This means that doing justice reinvestment well is not an overnight solution. It may take some time to see the returns of investing in social rather than corrective services. However, if communities are in control through this process, I believe the rewards will be deep seated and dramatic over time.

(ii) Bipartisan support for alternative to imprisonment

Bipartisan political support is unanimously cited as one of the greatest assets and challenges for justice reinvestment. All sides of politics need to put aside populist ‘tough on crime’ rhetoric and punitive policies in favour of an economically, socially and morally responsible approach to criminal justice issues.

Unfortunately, over the past five years we have seen a continuation and, in some cases, expansion of punitive policies. We have mandatory sentencing in New South Wales, Victoria, the Northern Territory, Western Australia, Queensland and South Australia.[453] Researchers also argue that tough bail legislation continues to contribute to imprisonment rates.[454]

In the Northern Territory, we have seen some concerning legislation in relation to alcohol, which also reflects this mood of popular punitive policies. As I mentioned in last year’s Social Justice and Native Title Report,[455] I am concerned about implications of Alcohol Mandatory Treatment and Alcohol Protection Orders. Both of these measures raise human rights concerns. Alcohol Protection Orders also have the potential to criminalise harmful alcohol use, and may lead to over policing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, particularly those who are homeless.

At the same time, we have also seen considerable cuts to legal and prevention services. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services are uniquely qualified to provide culturally secure services, and have the skills to ensure fair representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander defendants.

Punitive policies emerge because that is what politicians believe the public demands. There is no denying that there are times when heinous crimes do galvanise public opinion around punishment and deterrence, rather than rehabilitation and prevention. Indeed, I have always been clear that there are some people, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who need to be separated from society for a while.

However, I believe there is a serious need to reorientate the conversation towards safe communities. If we can create safer communities, this will lead to less offending which in turn means less people going to jail. This may show that imprisonment is not cost effective in these times of economic restraint. This, then, becomes something we can all agree on. Shifting this discourse is a major challenge but, as I will argue later in this chapter, I believe it is a challenge that we have the determination to tackle.

4.3 Justice targets

In the Social Justice Report 2009, Dr Tom Calma AO recommended that justice targets be added to the existing Closing the Gap targets. Like justice reinvestment, justice targets have now become one of the key advocacy points in addressing involvement with the criminal justice system.

In 2011, the Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Inquiry into Indigenous youth in the criminal justice system recommended that justice targets be included in the Closing the Gap targets.[456] Justice targets were an area of further discussion at the July 2011 meeting of the Standing Committee of the Attorneys-General, where an agreement was made to:

(a) significantly reduce the gap in Indigenous offending and victimisation and to accurately track and review progress with a view to reviewing the level of effort required to achieve outcomes

(b) ask First Ministers to refer to COAG the possible adoption of justice specific Indigenous closing the gap targets, acknowledging that in many instances their relative occurrence are due to variable factors outside the justice system.[457]

In August 2013, the Coalition committed to ‘provide bipartisan support for Labor’s proposed new Closing the Gap targets on incarceration rates’.[458] I welcome the Australian Government’s position but unfortunately, we are yet to see any progress on this.

In my request for information for this report, the Minister for Indigenous Affairs Nigel Scullion provided the following response:

- The Government considered the inclusion of additional targets in the Closing the Gap framework, including a justice-related target. The Council of Australian Governments agreed to a new target on school attendance at its meeting in May this year.

- The Government does not support the development of more targets than have already been agreed at this time. It considers that the adoption of too many targets may result in a loss of impact and focus for the existing targets.

- The Government is focused on making a practical difference on the ground to the lives of Indigenous Australians. Getting children to school and adults to work is the most effective approach to improving community safety and reducing incarceration.

- The Government will seek to engage with State and Territory governments, Indigenous communities and other stakeholders about what else can be done to achieve better justice-related outcomes.[459]

I welcome the new targets on school attendance. However, I am severely disappointed that the Minister is backing away from his previous commitment to justice targets. As I will argue below, there remains a compelling case for holistic justice targets.

(a) What are justice targets and why are they important?

In policy terms, targets are ‘goals which define the standard of success through assigning a value to an indicator that is expected to reach by a particular date’.[460]

Over the past five years, justice targets have come to refer to targets to address the overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as both offenders and victims in the criminal justice system. For instance, the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples’ Justice Policy recommended that targets be set to:

halve the gap in rates of incarceration for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [and] ...halve the rate at which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people report having experienced physical or threatened violence in the past 12 months.[461]

Targets, along with other performance measurement tools like performance indicators and benchmarking, are considered best practice in public policy development. Drawing on the perspective of developing health targets, the National Indigenous Health Equality Council states that:

Setting targets is one way to provide leadership, guidance and strategic direction. Targets can also be used effectively in monitoring progress towards strategic objectives.[462]

Targets encourage policy makers to focus on outputs and outcomes, rather than just inputs. It is not enough for governments to continue to report on what they do and spend, especially if that appears to be making little positive difference. Targets move us towards accountability and ensure that tax payer’s money is being spent in a results-focused way.

There is also a compelling human rights argument to be made for justice targets. Progressive realisation is a human rights concept embedded in art 2 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to which Australia is a party. It is recognised that achieving the full realisation of economic, social and cultural rights may take time, particularly for groups who have experienced historical patterns of discrimination. Progressive realisation means that States parties have an obligation to progressively work towards the realisation of a range of economic, social and cultural rights. Setting specific, time bound and verifiable targets is necessary to ensure progress is being made.

Many of these economic, social and cultural rights, for example the right to an adequate standard of living, the right to education, the right to work and the right to the highest standard of physical and mental health, are also linked to the underlying causes of crime.[463] Setting clear targets and timeframes for progression towards realisation of rights is one of the hall marks of the human rights-based approach.

(b) Lessons from Closing the Gap targets

There is much that we can learn from the process of setting targets, particularly in the health area, as part of Closing the Gap. I have been very supportive of the Closing the Gap targets for all the above reasons around accountability, strategic direction and leadership. While progress has been uneven in some areas, at the very least we know how we are tracking.

Of course, it is not the targets in and of themselves that have led to changes but the enhanced level of cooperation at the Council of Australian Governments level and targeted increases in funding. However, without the targets in place to guide this work, and a mechanism whereby the Prime Minister annually reports to Parliament against these targets, there is a real risk that our progress would stall.

Targets have made the gap between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and non-Indigenous Australians visible. This is exactly what needs to happen on the issue of overrepresentation with the criminal justice system as victims and offenders. I would argue that most Australians know little about this problem, but many would be alarmed at the statistics. Raising the profile of the issue through targets can help build sustained pressure for improvement.

Targets were not just pulled out of thin air. There was a considered and technical process which examined options for ambitious, but also realistic, targets. Based on this experience, the National Indigenous Health Equality Council has recommended the usage of the ‘SMART’ model for setting targets:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Achievable

- Realistic

- Time-bound.[464]

The National Indigenous Health Equality Council has also identified the importance of consultation.[465] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals and organisations had a central role in formulating health targets.

Finally, we have seen a high level of commitment to the Closing the Gap targets. The level of bipartisan support has been a significant key to the success of Closing the Gap.

(c) Options for developing justice targets

Part of the reason that justice targets have not been developed yet may be that setting targets can be both a complex and contested task. There are certainly challenges in data collection that would hamper measuring progress against targets.[466] Agreeing on the actual targets will also require stakeholder engagement and consensus building.

However, we are building on a strong base of empirical evidence to set justice targets. There is robust research identifying the underlying causes, or risk factors, for involvement with the criminal justice system. Dr Don Weatherburn argues that the key risk factors for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander involvement with the criminal justice system are:

- poor parenting, neglect and child abuse

- poor school attendance, performance and retention

- unemployment

- drug and alcohol abuse.[467]

It is worth noting that these risk factors also apply to non-Indigenous individuals. However, research shows that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience them at higher rates.[468] Dr Don Weatherburn argues that these risk factors form:

a vicious cycle. Parents exposed to financial or personal stress or who abuse drugs and/or alcohol are more likely to abuse or neglect their children. Children who are neglected or abused are more likely to associate with delinquent peers and do poorly at school. Poor school performance increases the risk of unemployment, which in turn increases the risk of involvement in crime. Involvement in crime increases the risk of arrest and imprisonment, both of which further reduce the chances of legitimate employment, while at the same time increasing the risk of drug and alcohol abuse.[469]

I quote this example not to paint a picture of despair, but to illustrate how the current range of targets in Closing the Gap will struggle to be achieved if we do not do something about the powerful undercurrents of the criminal justice system. For instance, you cannot expect to achieve targets around education, employment or health if you do not look holistically at justice risk factors as well. Similarly, you cannot expect to achieve a justice target, for instance, a reduction in the rate of imprisonment or victimisation, without addressing these underlying factors.

In last year’s Social Justice and Native Title Report, I argued that justice targets:

need to include obvious indicators such as rates of imprisonment, recidivism and victimisation but to be really successful we need to look more holistically...I would like to see indicators such as involvement with the child protection system, use of diversionary programs, successful transitions to school and employment also considered.[470]

(i) Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage framework

Since 2002, the Steering Committee for Review of Government Services, within the Productivity Commission, has been regularly producing the Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage report. These reports were originally commissioned by the Council of Australian Governments and provide a framework for reporting against key indicators of disadvantage. Reporting is based on a mixture of Census, survey and administrative data.[471]

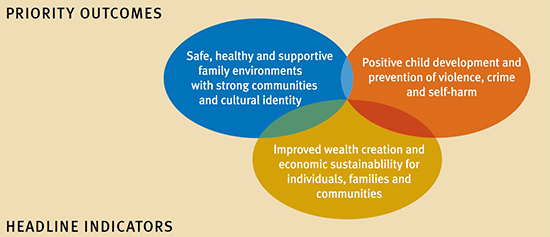

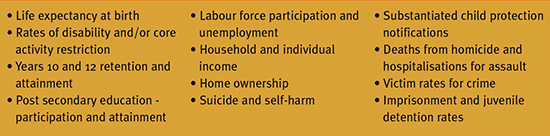

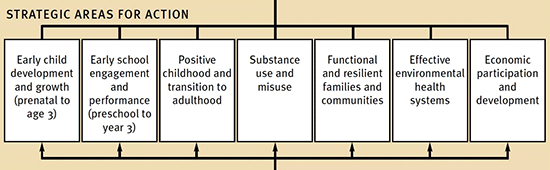

The Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage framework, shown at Figure 4.2 sets out three tiers:

- priority outcomes

- headline indicators

- strategic areas for action.

Figure 4.2: The framework[472]

Table 4.2: Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage headline indicators - 2011

|

Indicator

|

Measure

|

|---|---|

|

4.10 Substantiated child abuse and neglect

|

|

|

4.11 Family and community violence

|

|

|

4.12 Imprisonment and juvenile detention

|

|

The next tier, below, includes strategic areas for action. Again, there are some measures that are very relevant to the task of setting justice targets, as shown in Table 4.3. For the purposes of this analysis, I have only included the measures that are outside the current Closing the Gap targets.

Table 4.3: Strategic areas for action

|

Strategic areas for action

|

Relevant measure

|

|---|---|

|

Positive childhood and transition to adulthood

|

|

|

Substance use and misuse

|

|

|

Functional and resilient families and communities

|

|

In the first instance, I believe that this list of indicators and measures provides a good basis for developing both ‘headline’ justice targets and a range of sub-targets or proxies. As we have seen from the experience of Closing the Gap, it is important to set both of these mechanisms. Headline targets will allow us to measure the overall outcome we want to achieve, while the sub-targets or proxies allow us to monitor how we are tracking towards the ‘headline target’.

Further, we can be confident that these indicators used by the Productivity Commission are based on robust data collections that are readily accessible.

A process of consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations and other experts in the justice sector will be needed to confirm the relevance of these indicators and/or suggest additional indicators. For instance, the provision of post-release support services could be included, or there could be information about the provision of victim support services. The important thing is that we are not starting with a blank piece of paper. Instead, we are building on existing and available data and indicators to start the conversation in a focused way. The next challenging task is actually setting the target, once the indicators are decided.

The involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and experts in the justice sector will be crucial to achieve success. As I will discuss below, I believe we are well placed to provide this input in a strategic way.

I strongly urge the Minister for Indigenous Affairs to reconsider his advice to me for this report and return to the pre-election commitment to develop justice targets as outlined above.

4.4 National Justice Coalition

The need to create a new conversation about safer communities requires leadership and unity. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander advocates and others in the sector have been arguing tirelessly for criminal justice reform. However, our impact in this area may have been hampered by a lack of coordination and strategic approach.

For this reason, I am wholeheartedly throwing my support behind the newly formed National Justice Coalition (NJC).

The NJC consists of a group of peak Aboriginal, human rights and community organisations from across Australia, and was formed with the goal of reducing the overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the criminal justice system by promoting safer communities.

Over the past year, significant work has been undertaken to form this coalition of leading Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander human rights and community organisations from across Australia. They have made a joint commitment to work together to respond to this social crisis. The commitment to collaborate on this issue is unprecedented.

The NJC Co-Chairs are Mr Shane Duffy and Ms Kirstie Parker. Text Box 4.4 lists the founding organisations in the NJC.

Text Box 4.4: National Justice Coalition members

- National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services

- National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples

- Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care

- Indigenous Doctors Association

- National Family Violence Prevention Legal Services

- National Indigenous Drug and Alcohol Committee

- National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Mick Gooda

- Human Rights Law Centre

- Oxfam Australia

- Australian Council of Social Service

- ANTaR

- Amnesty International Australia

- Sisters Inside

- Federation of Community Legal Centres (VIC)

- Australian National Council on Drugs

- First Peoples Disability Network Australia.

The NJC has been successful in gaining philanthropic funding for a Principal Adviser for two years. This is a significant achievement and places the NJC in good stead to become a professional, resourced body that can develop a comprehensive workplan.

We are still in the formative phase of the NJC. The first formal planning workshop for the NJC took place in August 2014, and we anticipate that the position of Principal Adviser will be filled shortly. The NJC work plan and campaign is still being mapped out at the time of writing.

However, I am very optimistic that with the lessons that we have learnt from the successes of the Close the Gap Campaign for Indigenous health equality, we have a good chance of generating positive change. Firstly, there is a broad base of organisations involved in the group, able to bring their unique expertise and contacts to the campaign. Secondly, like the Close the Gap Campaign, we have not rushed the important process of relationship building and identification of common ground. This means there is a solid base to the NJC.

Having a strong, united voice on issues related to the criminal justice system will help raise the profile of this issue. The NJC will be able to champion the creation of safer communities, as well as suggest solutions based on members’ extensive experience in the field. This will be invaluable as we continue to advocate for issues such as justice reinvestment and justice targets into the future.

4.5 Conclusion and recommendations

While the overall picture of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ involvement in the criminal justice system is a troubling one, there is nonetheless cause for real optimism. In the past five years, we have seen the concept of justice reinvestment being embraced as another tool to create safe communities, with communities Bourke and Cowra leading the way. This grass roots level of social change has exciting possibilities that could inform developments across the nation.

The support for justice targets in our communities, and with our advocates, remains strong. With the establishment of the National Justice Coalition, we are now getting to a place, like the Close the Gap campaign, where we will have the right mix of expertise and leadership to hopefully progress the push for justice targets. I am hopeful that the National Justice Coalition will be the circuit breaker we need to get safer communities on the national agenda so that we start to see real improvements on the ground in our communities all over Australia.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: The Australian Government revises its current position on targets as part of Closing the Gap, to include holistic justice targets aimed at promoting safer communities.

Recommendation 2: The Australian Government actively consults and works with the National Justice Coalition on justice related issues.

Recommendation 3: The Australian Government takes a leadership role on justice reinvestment and works with states, territories and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to identify further trial sites.

[409] C Cunneen, ‘Time to arrest rising Aboriginal prison rates’ (2013) 8 Insight Issue 22, p 24. At: http://justicereinvestment.unsw.edu.au/node/34 (viewed 1 October 2014).

[410] C Cunneen, ‘Time to arrest rising Aboriginal prison rates’, above.

[411] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Imprisonment Rates, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4517.0main+features322013 (viewed 1 October 2014).

[412] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Youth Detention Population in Australia 2013 (2013), p vii. At http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129545393 (viewed 1 October 2014).

[413] Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage 2011, Productivity Commission (2011), pp 4.123 - 4.124. At http://www.pc.gov.au/gsp/overcoming-indigenous-disadvantage/key-indicators-2011 (viewed 1 October 2014).

[414] T Calma, Social Justice Report 2009, Australian Human Rights Commission (2009), ch 2. At: https://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/social-justice-report-2009 (viewed 1 October 2014).

[415] D Brown, M Schwartz and L Boseley, ‘The Promises of Justice Reinvestment’ (2012) 37(2) Alternative Law Journal 96, p 97.

[416] J Austin and G Coventry, ‘A Critical Analysis of Justice Reinvestment in the United States and Australia’ (2014) 9(1) Victims & Offenders: An International Journal of Evidence-based Research, Policy, and Practice 126; University of New South Wales, Australian Orientated Sources, http://justicereinvestment.unsw.edu.au/node/31 (viewed 1 October 2014).

[417] Australian Justice Reinvestment Project, Newsletter (July 2014). At http://justicereinvestment.unsw.edu.au/sites/justicereinvestment.unsw.edu.au/files/AJRP%20Newsletter%20July%202014.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014).

[418] Council of State Governments Justice Center, Justice Reinvestment , http://csgjusticecenter.org/jr/ (viewed 1 October 2014).

[419] D Brown, M Schwartz and L Boseley, ‘The Promises of Justice Reinvestment’, note 7, p 97.

[420] D Brown, M Schwartz and L Boseley, ‘The Promises of Justice Reinvestment’, above, p 97.

[421] Council of State Governments Justice Center, Facts and Trends, http://csgjusticecenter.org/justice-reinvestment-facts-and-trends/ (viewed 1 October 2014).

[422] D Brown, M Schwartz and L Boseley, ‘The Promises of Justice Reinvestment’ (2012), note 7, p 98.

[423] For Victoria see: Smart Justice Project, Welcome to Smart justice, http://www.smartjustice.org.au/; for Western Australia see: Deaths In Custody Watch Committee, Build Communities Not Prisons Campaign, http://www.deathsincustody.org.au/build-communities-not-prisons-campaign; for Queensland see: Project 10%, Project 10%, http://www.project10percent.org.au/; for the Australian Capital Territory see: Australian National University, Justice Reinvestment Forum: 2 August 2012, http://ncis.anu.edu.au/events/past/jr_forum.php (all pages viewed 1 October 2014).

[424] C Heard, The Future of Justice Reinvestment, SBS TV (27 July 2013). At http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2013/07/27/blog-future-justice-reinvestment (viewed 1 October 2014).

[425] Family Violence and Legal Services Prevention Services Victoria, Submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs on the value of justice reinvestment in Australia (2013). At http://www.fvpls.org/images/files/FVPLS%20Victoria%20-%20Justice%20Reinvestment%20Submission.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014); See also North Australian Aboriginal Family Violence Legal Service, National Family Violence Prevention Legal Services, Submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs on the value of justice reinvestment in Australia (2013). At http://www.nationalfvpls.org/images/files/National_FVPLS_Forum_-_Justice_Reinvestment_Submission.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014).

[426] Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee, Value of a justice reinvestment approach to criminal justice in Australia, above.

[427] Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee, Parliament of Australia, Value of a justice reinvestment approach to criminal justice in Australia (2013). At http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Legal_and_Constitutional_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2010-13/justicereinvestment/report/index (viewed 1 October 2014).

[428] Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee, Parliament of Australia, Minority Report from Coalition Senators on the value of a justice reinvestment approach to criminal justice in Australia (2013). At http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Legal_and_Constitutional_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2010-13/justicereinvestment/report/d01 (viewed 1 October 2014).

[429] House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, Parliament of Australia, Doing Time –Time for Doing: Indigenous youth in the criminal justice system (2011). At http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House_of_Representatives_Committees?url=atsia/sentencing/report.htm (viewed 1 October 2014).

[430] House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, Doing Time –Time for Doing, above, p 36.

[431] Community Development and Justice Standing Committee, Parliament of Western Australia, Making our prisons work: An inquiry into the efficiency and effectiveness of prisoner education, training and employment strategies, Report No. 6 (2010). At http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/parliament/commit.nsf/(WebInquiries)/6228E6A9C090FDB9482578310040D2B8?opendocument (viewed 1 October 2014).

[432] Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee, Parliament of New South Wales, Access to Justice (2009). At www.nswbar.asn.au/circulars/2009/dec09/access.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014).

[433] Noetic Solutions, A Strategic Review of the New South Wales Juvenile Justice System: Report for the Minister for Juvenile Justice (April 2010). At http://www.djj.nsw.gov.au/pdf_htm/publications/general/Juvenile%20Justice%20Review%20Report%20FINAL.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014).

[434] D Brown, M Schwartz and L Boseley, ‘The Promises of Justice Reinvestment’, note 7, p 99.

[435] Office of Communities, Community Portrait, Bourke: A portrait of the Aboriginal community of Bourke, compared with NSW, from the 2011 and earlier Censuses, Aboriginal Affairs NSW Government (2011). At http://aboriginalaffairs.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/130910-Community-Portrait-Bourke.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014).

[436] A Vivian and E Schnierer, Factors affecting crimes rates in Indigenous communities in NSW: a pilot study in Bourke and Lightening Ridge: Community Report November 2010, Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning University of Technology (2010). At http://www.jumbunna.uts.edu.au/pdfs/research/FinalCommunityReportBLNov10.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014).

[437] A Vivian and E Schnierer, Factors affecting crimes rates in Indigenous communities in NSW, above.

[438] A Vivian and E Schnierer, Factors affecting crimes rates in Indigenous communities in NSW, above.

[439] A Vivian and E Schnierer, Factors affecting crimes rates in Indigenous communities in NSW, above.

[440] Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Trends and patterns in domestic violence assaults, http://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/bocsar/bocsar_mr_bb61.html (viewed 1 October 2014).

[441] A Vivian and E Schnierer, Factors affecting crimes rates in Indigenous communities in NSW, note 28.

[442] NSW Ombudsman, Inquiry into service provision to the Bourke and Brewarrina communities - A special report to Parliament under section 31 of the Ombudsman Act 1974 (2010). At http://www.ombo.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/3348/SR_ServiceProvisionBourke_Dec10.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014).

[443] R Olding and N Ralston, ‘Bourke tops list: more dangerous than any country in the world’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 February 2013. At http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/bourke-tops-list-more-dangerous-than-any-country-in-the-world-20130201-2dq3y.html (viewed 1 October 2014).

[444] Collective Impact Australia, What is collective impact?, http://collectiveimpactaustralia.com/about/ (viewed 1 October 2014).

[445]Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011 Census Quickstats, http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/quickstat/POA2794?opendocument&navpos=220 (viewed 1 October 2014).

[446] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Cowra (A) LGA, http://stat.abs.gov.au/itt/r.jsp?RegionSummary®ion=12350&dataset=ABS_NRP9_LGA&geoconcept=REGION&datasetASGS=ABS_NRP9_ASGS&datasetLGA=ABS_NRP9_LGA®ionLGA=REGION®ionASGS=REGION (viewed 1 October 2014).

[447] ‘Rethinking the justice system’, Cowra Guardian, 5 June 2013. At http://www.cowraguardian.com.au/story/1552398/rethinking-the-justice-system/ (viewed 1 October 2014).

[448] ‘Rethinking the justice system’, Cowra Guardian, above. At http://www.cowraguardian.com.au/story/1552398/rethinking-the-justice-system/ (viewed 1 October 2014).

[449] University of New South Wales, Justice Reinvestment Project, Fact Sheet: JR in the USA – Fieldwork Reflections (2014). At http://justicereinvestment.unsw.edu.au/sites/justicereinvestment.unsw.edu.au/files/AJRP%20Fact%20Sheet%20Reflections%20CY.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014).

[450] University of New South Wales, Justice Reinvestment Project, Fact Sheet, above.

[451] University of New South Wales, Justice Reinvestment Project, Fact Sheet, above.

[452] University of New South Wales, Justice Reinvestment Project, Fact Sheet, above.

[453] Appendix 2 of this report has full details of the current mandatory sentencing legislation.

[454] D Brown, ‘Looking Behind the Increase in Custodial Remand Populations’ (2013) 2(2) International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 80. At https://www.crimejusticejournal.com/article/view/84 (viewed 1 October 2014).

[455] M Gooda, Social Justice and Native Title Report 2013, Australian Human Rights Commission (2013), ch 4. At http://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/social-justice-and-native-title-report-2013 (viewed 1 October 2014).

[456] House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, Doing Time –Time for Doing, note 22.

[457] Standing Committee of Attorneys-General, Communique 21 & 22 July 2011 (2011). At http://www.lccsc.gov.au/agdbasev7wr/sclj/documents/pdf/scag_communique_21-22_july_2011_final.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014).

[458] N Scullion, ‘Labor’s Indigenous Affairs plans short on results’ (Media Release, 8 August 2013). At http://www.nigelscullion.com/media-hub/indigenous-affairs/labor%E2%80%99s-indigenous-affairs-plans-short-results (viewed 1 October 2014).

[459] N Scullion, Correspondence to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, 31 August 2014.

[460] National Indigenous Health Equality Council, National Target Setting Instrument Evidence Based Best Practice Guide (2010), p 4.

[461] National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, National Justice Policy (2013), p 16. At http://nationalcongress.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/CongressJusticePolicy.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014).

[462] National Indigenous Health Equality Council, National Target Setting Instrument Evidence Based Best Practice Guide, note 52, p 4.

[463] Human Rights Law Centre, Submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs Inquiry into the value of a justice reinvestment approach in Australia (2013), p 10. At http://www.hrlc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/HRLC_Submission_Justice_Reinvestment.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014).

[464] National Indigenous Health Equality Council, National Target Setting Instrument Evidence Based Best Practice Guide, note 52, p 6.

[465] National Indigenous Health Equality Council, National Target Setting Instrument Evidence Based Best Practice Guide, above, p 5.

[466] National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, National Justice Policy, note 53.

[467] D Weatherburn, Arresting Incarceration - Pathways out of Indigenous Imprisonment (2014), p 74.

[468] D Higgins and K Davis, Law and justice: prevention and early intervention programs for Indigenous youth (2014), Closing the Gap Clearinghouse Resource Sheet no. 34. At http://www.aihw.gov.au/uploadedFiles/ClosingTheGap/Content/Our_publications/2014/ctg-rs34.pdf (viewed 1 October 2014).

[469] D Weatherburn, Arresting Incarceration, note 59, pp 86-87.

[470] M Gooda, Social Justice and Native Title Report 2013, note 47, ch 4.

[471] Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2003, Productivity Commission (2003), p 4. At http://www.pc.gov.au/gsp/overcoming-indigenous-disadvantage (viewed 1 October 2014).

[472] Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage, above, p 4.