Inquiry into the Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Act 1999 and Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Agency (2009)

Inquiry into the Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Act 1999 and Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Agency

Australian Human Rights Commission

Submission to the Australian Government Office for Women

30 October 2009

-

Download Word [ 1.6 MB]

Download Word [ 1.6 MB]  Download PDF [ 630 KB ]

Download PDF [ 630 KB ]

Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Executive Summary

- 3 Table of Recommendations

- 4 Diagrams of proposed national gender equality monitoring and employer compliance frameworks

- 5 Identifying the problem: is there gender equality in Australian workplaces?

- 5.1 Introduction: findings of the Listening Tour

- 5.2 Women’s workforce participation

- 5.3 Pay equity and starting salaries

- 5.4 Women in management and leadership positions

- 5.5 Prevalence of sexual harassment

- 5.6 Pregnancy discrimination in the workplace

- 5.7 Impact of unpaid work and family and carer responsibilities

- 5.8 Gendered ageism

- 5.9 Conclusion

- 6 The case for reform: why does achieving gender equality in Australian workplaces matter?

- 6.1 Introduction

- 6.2 Gender equality will improve women’s economic security

- 6.3 Gender equality will improve business and organisational performance

- 6.4 Gender equality will improve national productivity

- 6.5 Gender equality will fulfil Australia’s international human rights and labour rights obligations

- 7 The current context: what are the national laws and institutional arrangements?

- 7.1 Introduction

- 7.2 National laws impacting on gender equality in the workforce

- 7.3 Institutional arrangements under national laws impacting on gender equality in the workforce

- 7.4 Table comparing Australia’s gender equality laws & institutions

- 7.5 Relationship and interaction between gender equality institutions

- 8 Reform proposals: what needs to change?

- 8.1 Introduction

- 8.2 Greater clarity and cohesion amongst national gender equality regulatory schemes

- 8.3 Promotion of gender equality rather than equal opportunity for women

- 8.4 Improved transparency and accountability at the national level

- 8.5 Greater emphasis on outcomes rather than processes in Employer Reporting Obligations

- 8.6 Greater certainty for business and employers

- 8.7 Full coverage of employers

- 8.8 Targeted effort to close the gender pay gap: a National Pay Equity Strategy

- 8.9 Special measures to fast track achieving of substantive gender equality in leadership

- 8.10 Associated reforms

- 9 Appendices

- 9.1 Appendix 1: Australia’s International Human and Labour Rights Obligations: Detailed Descriptions

- 9.2 Appendix 2: Detail of the Key Features of Australia’s National Laws and Institutional Arrangements which impact on Gender Equality in the Workforce

- 9.3 Appendix 3: Comparative Gender Equality Laws and Institutional Arrangements in the UK, Canada, New Zealand and Norway

1 Introduction

-

The Australian Human Rights Commission (the

Commission)[1] welcomes the

opportunity to make this Submission to the Australian Government Review of the Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Act 1999 (Cth) (the EOWW

Act) and the Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Agency (the

EOWA). -

The Commission is Australia’s national human rights institution.

-

The Commission has previously made a range of submissions and published

reports about improving gender equality outcomes in Australian workplaces. The

Commission refers the EOWA Review to this previous body of work,

including:-

It’s About Time: Women, Men, Work and Family (2007);[2]

-

Listening Tour Community Report (2008);[3]

-

Submissions One and Two to the Productivity Commission Inquiry into Paid

Leave for Parents (2008);[4] -

Submission to the Inquiry into Better Support for Carers (2008);[5]

-

Submission to the Senate Committee Inquiry into the Effectiveness of the

Sex Discrimination Act (2008) (submission to the SDA

Review);[6] -

Submission to the House of Representatives Inquiry into Pay Equity (2008);[7]

-

Submission to the Inquiry into Australia’s Future Tax System

(Retirement Income System) (2009)[8] ; and -

Accumulating Poverty? Women’s experiences of inequality over the

lifecycle (2009)[9]

-

-

The Commission builds on this body of work in order to present this

Submission to the EOWA Review. It also makes a range of new recommendations,

particularly directed to reforms to the EOWW Act and Agency, as well as changes

to the ASX corporate governance arrangements.

2 Executive

Summary

-

The EOWA Review provides a unique opportunity to strengthen

Australia’s national laws and institutions that regulate gender equality

in Australian workplaces. -

Gender inequality continues to be a significant problem in Australia, and

progress to address this inequality has stalled. For example;-

Australia is ranked 1st on women’s educational attainment

but only 50th for women’s workforce participation; -

Women are only paid 83% of the pay of men for work of comparable value

(based on ordinary full-time earnings); -

Women hold only 8.3% of Board Directorships, 2% of CEO Roles, and 10.7% of

Senior Executive Positions; -

22% of women (compared to 5% of men) have experienced sexual harassment at

work; -

Almost one in 5 pregnant women in paid employment experience difficulty in

her workplace linked to her pregnancy; -

Women continue to do the vast majority of unpaid work, even when they are

also in paid work; and -

Women on average accumulate only half the retirement savings of men over

their lifetime.

-

-

The case for reform is clear.

-

There are several major benefits which would flow from achieving gender

equality in the workplace. In particular, achieving gender equality will

significantly improve:-

women’s economic security;

-

business and organisational performance; and

-

national productivity.

-

-

It would also ensure that Australia has met its international human rights

and labour rights obligations. -

Achieving gender equality in Australian workplaces should be a national

priority. -

The EOWW Act and Agency, the subjects of this Review, form one of the three

major national statutory schemes that regulate gender equality in the workplace.

The other national statutory schemes are:-

The Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) (the SDA), administered by the

Australian Human Rights Commission (the Commission), including the Sex

Discrimination Commissioner (SDC); and -

The Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FWA), administered by Fair Work

Australia and the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWA/Ombudsman).

-

-

Another important regulatory element is the ASX Corporate Governance

arrangements for publicly listed companies. -

Whilst each of these national statutory schemes makes positive contributions

to promoting gender equality in the workplace, the evidence is clear that the

current system needs to be reformed. -

There are several objectives that should drive the reform of the EOWW Act

and Agency and associated legislative and institutional arrangements. These

are:-

greater clarity and cohesion amongst national regulatory schemes;

-

promotion of gender equality rather than equal opportunity for women;

-

improved transparency and accountability at the national level;

-

greater emphasis on outcomes rather than processes in mandatory Employer

Reporting Obligations; -

greater certainty for business and employers;

-

full coverage of employers;

-

targeted effort to close the gender pay gap; and

-

special measures to fast track achieving substantive equality in

leadership.

-

-

These objectives are discussed in order

below.

Greater clarity and

cohesion amongst national regulatory schemes

-

There is currently a lack of clarity about roles, responsibilities and

priorities for the EOWW Act and Agency, the SDC/Commission and the

FWA/Ombudsman. This leads to the national regulatory arrangements being less

effective than they could be. The Commission proposes that the following lead

roles and responsibilities for each of the three statutory schemes should

underpin the reform process: -

The EOWA, as a gender specific agency, should lead:

-

coordination within the Australian Government on action to achieve gender

equality in Australian workplaces in partnership with the Australian Government

Office for Women (OFW); -

collaboration with employers, including Australian business, Australian

Government departments and statutory authorities, to promote strategies, and

positive action by employers to achieve gender equality in Australian

workplaces, including through education.

-

-

The Commission, represented where appropriate by the SDC, as a statutory

authority with gender-specific functions and with an established enforcement and

monitoring role, should lead:-

enforcement, particularly at a systemic level, to ensure compliance with

gender equality workplace obligations; -

education and advocacy about the gender equality rights of workers; and

-

independent monitoring and reporting to the Australian Parliament and the

public on progress in achieving substantive gender equality, including in

Australian workplaces.

-

-

The FWA/Ombudsman, as general industrial relations mechanisms, should

collaborate with the:-

EOWA in its lead roles; and

-

SDC/Commission in its lead roles

to positively

contribute to systemic action required to achieve gender equality in Australian

workplaces. -

-

The EOWA, as the primary agency charged with the promotion of gender

equality in the workplace as part of the Australian Government, should therefore

be retained as a stand alone regulator with gender equality in the workplace as

its sole priority. It should be linked to the participation and employment areas

of government, and work closely with the SDC/Commission and FWA/Ombudsman to

drive systemic change within Australian workplaces (see Recommendations 1 and

2).

Promotion of gender

equality rather than equal opportunity for women

-

The core purpose of the EOWW Act and Agency should change from being the

promotion of equal opportunity for women to promoting gender equality in the

workplace. This change in purpose is to ensure that action by the EOWA is

clearly directed towards promoting equal outcomes for women and men (substantive

equality) rather than ensuring that women have the same formal opportunities

(formal equality). It is well established that, in order for women’s

experience of paid work to be transformed, there may be a need for women to be

treated differently to men. It is also well established that men may also need

to have changed experiences of paid work in order to lead to more equal outcomes

between women and men. -

The EOWW Act should therefore be amended to change its name to the Gender

Equality in the Workplace Act, the EOWA should be renamed the Gender

Equality in the Workplace Agency, and the EOWW Act should include the

achievement of gender equality as a key object (see Recommendations 3 and

4).

Improved transparency and

accountability at the national level

-

There is also a need for greater transparency and accountability at the

national level about what is working, and what needs to change, in order to make

adequate progress in improving gender equality outcomes. At the present time,

there is a body of excellent research and reporting that is undertaken on

specific issues about gender equality, both inside and outside of the workplace.

However, there is no national framework to enable Australia as a nation to track

systemic changes which impact on overall gender equality outcomes. -

In particular, there needs to be an agreed set of national gender equality

benchmarks and indicators against which progress can be independently monitored.

This national monitoring framework would enable time-bound targets to be set for

commitments to improve gender equality outcomes, including in the workforce. The

national monitoring framework would also inform the design of the mandatory

employer reporting obligations to the EOWA, discussed further below. -

The Commission repeats its earlier recommendations, particularly in its Submission to the SDA Review (2008) that the SDC be given the role of

independent monitoring and analysis of progress towards achieving gender

equality in Australia. The Commission should be given the resources to develop

the National Gender Equality Benchmarks and Indicators, in collaboration with

the EOWA, the OFW and other key agencies, including the Australian Bureau of

Statistics (ABS). The Commission, as the fully independent statutory office at

the national level with gender specific functions, is particularly well placed

to oversee this development work (see Recommendation 5).

Greater emphasis on outcomes

rather than processes in mandatory employer reporting obligations

-

The Commission considers that the regulation of employers should be done on

the principle of better regulation, rather than more regulation. -

It proposes that, under the EOWW Act, the design of the mandatory annual

employer reporting obligations should have a stronger focus on tracking actual

changes in gender equality within the workplace. This could include, for

example, changes in the pay gap, flexible work arrangements, and gender

diversity in leadership roles, rather than processes such as training and

mentoring schemes. -

The EOWA should be required to issue employers with an EOWA Certification

that they have met their employer reporting obligations, and the Act should

require that the employer publishes both their report and Certification to all

staff to enhance accountability back into the workplace. The Certifications

should also be published in the Annual Report, including ASX Annual Reports

where applicable. -

EOWA certification should be a pre-condition for organisations to enter

government contracts, or provide the Australian government with goods and

services. -

The EOWA should have the lead role in designing resources for employers to

improve gender equality outcomes, including through online services.

Importantly, it should also have the power to go behind employer reports to

verify the accuracy of reported outcomes. -

Finally, in conjunction with the EOWA, employers, groups of employers or

industries should have the option of developing voluntary Gender Equality Action

Plans which set clear time-bound targets for improved gender equality and

strategies for achieving those targets (see Recommendations 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

and 11).

Greater certainty

for business and employers

-

In order to offer benefits to employer/employer groups for developing

concrete Gender Equality Action Plans, the Commission also proposes that it be

possible for these Plans to be submitted, at the option of the employer/employer

groups, for legal recognition under the SDA as a ‘special measure’

or legal instrument. This recognition would provide greater certainty for the

employer/employer groups, operating either as a defence against claims of

discrimination under the SDA (and claims of adverse action under the FWA) or at

least creating a presumption of compliance with employer obligations under the

national gender equality regulatory schemes. -

This reform would be a mid-way reform towards the development of standards

under the SDA (and FWA) that apply more broadly, and the creation of more

general positive duty obligations on employers under the SDA, both of which were

proposed by the Commission as ‘options for reform’ as part of its Submission to the SDA Review (2008) (see Recommendation 12).

Full coverage of

employers

-

Currently, government departments and statutory agencies with 100 employees

or more are not part of the EOWW Act regulatory scheme. In addition, many

employers that technically are covered do not currently report, as they are not

easily identified. The Act should be amended to extend coverage to government

departments and statutory agencies. -

A mechanism should also be established to identify annually all employer

organisations that have 100 employees or more and advise the EOWA of the names

of these organisations (see Recommendation 13 and

14).

Targeted effort to close

the gender pay gap

- The gender pay gap remains a major problem in Australia, and current

arrangements for addressing pay inequity are inadequate. Subject to the outcomes

of the House of Representatives Inquiry into Pay Equity, the Commission proposes

that the EOWA and the Commission should be funded to enable the SDC to partner

in the development of a National Pay Equity Strategy. This strategy should

include the gender pay gap component of the national monitoring framework,

implementation of the Pay Equity Tool, and making pay rates more transparent

(see Recommendations 15 and 16).

Special measures to fast track

achieving substantive equality in leadership

-

The Commission considers that, in light of Australia’s poor record on

improving women’s leadership roles in Australian businesses, and at board

level generally, there is a case now for putting in place special measures to

fast track reform in this area. -

The Commission considers that the Australian Government has a leadership

role to play, and should therefore immediately adopt a mandatory national

benchmark of 40% gender diversity on all government boards within three years. -

For other boards, there should be a two stage reform process. Initially, it

should be mandatory for all publicly listed companies to adopt three and five

year disclosable targets for improving gender diversity on both their boards,

and at senior executive level. The exact target set can be at the discretion of

the employer during this first stage. These targets should be reported to the

ASX through the annual reporting process. ASX companies should also be required

to report on their compliance with employer reporting obligations under the EOWW

Act, by way of exception reporting. -

After five years, if there is a lack of substantial progress, the Australian

Government should consider introducing mandatory gender quotas for boards, at

least on ASX publicly listed companies, with penalties for failing to meet

quotas within a specified period of time (see Recommendations 17, 18, 19 and

20).

Associated

Reforms

-

The Commission also proposes reforms to the SDA and to the FWA regulatory

schemes to foster greater links and cohesion amongst the three national

statutory schemes that impact on gender equality in the workplace. -

The SDA should be amended to implement the recommendations of the Senate

Standing Committee Inquiry into the SDA. In addition, the SDC/Commission should

be required to notify the FWA/Ombudsman and the EOWA Agency when it commences

systemic action under the reformed SDA. -

The FWA/Ombudsman should also be required to notify the SDC/Commission when

it commences systemic action to promote gender equality in the workplace,

particularly when it commences an investigation or proceedings for relevant

adverse action claims (see Recommendations 21, 22 and 23). -

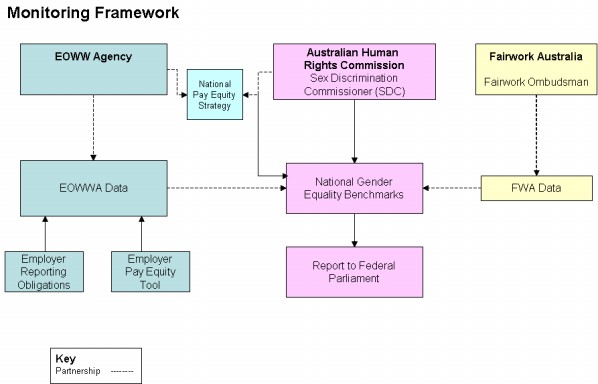

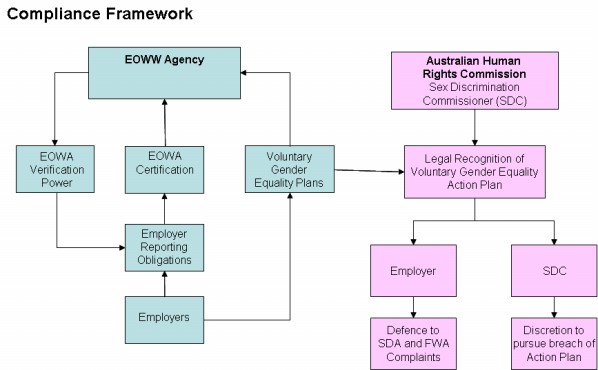

A complete list of Recommendations is set out in Section 3 of this

Submission. Section 4 presents two diagrams, being the proposed National

Gender Equality Monitoring Framework, as well as the proposed Employer

Compliance Framework. -

Sections 5 to 7 are for Information, with summaries of the nature and

extent of gender inequality in the workplace (Section 5), why achieving gender

equality matters (Section 6) and the national legislative and institutional

arrangements currently in place that regulate gender equality in the workplace

(Section 7). -

Section 8 sets out the detailed Proposals for Reform, and the 23

Recommendations. -

The Submission also provides more detailed information in the appendices,

including descriptions of Australia’s relevant international human rights

and labour rights obligations (Appendix 1), the national legislative and

institutional arrangements (Appendix 2) and comparisons with other countries,

particularly the United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand and Norway (Appendix

3).

3 Table of

Recommendations

|

Objective |

Recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Greater clarity and cohesion amongst national regulatory schemes |

Recommendation 1: Status of the EOWA The EOWA should be the principal point of contact of the Australian Recommendation 2: Statutory Links of the EOWA The EOWW Act should require the Agency to work closely with the |

|

Promotion of gender equality rather than equal opportunity for women |

Recommendation 3: Name of the EOWW Act and Agency The EOWW Act should be renamed the Gender Equality in the Workplace Recommendation 4: Objects of the EOWW Act The objects of the EOWW Act should include the promotion of substantive

|

|

Improved transparency and accountability at national level |

Recommendation 5: Independent Monitoring of National Gender Equality The Commission, acting through the SDC, should be the lead agency to The EOWA and other relevant bodies, including the FWA/Ombudsman and the ABS The Commission, acting through the SDC, should independently report to the |

|

Greater emphasis on outcomes rather than processes in Employer Reporting |

Recommendation 6: Employer reporting obligations Employer reporting obligations should focus on the achievement of equal Recommendation 7: EOWA certification When employers meet their employer reporting obligations under the EOWW

Recommendation 8: EOWA EOWA Certification should be a pre-condition of providing goods and Recommendation 9: EOWA Employer Capacity Building The Agency should play the lead role in supporting employers to achieve Recommendation 10: EOWA verification EOWA should be empowered to conduct a verification process to establish Recommendation 11: Voluntary Gender Equality Action Plans Employers, groups of employers or industry groups may voluntarily adopt |

|

Greater certainty for business and employers |

Recommendation 12: Voluntary Gender Equality Action Plans may be legally The SDA should be amended to provide that voluntary Gender Equality Action Depending on the model chosen, compliance with voluntary Action Plans

|

|

Full coverage of employers |

Recommendation 13: Coverage to Government and Statutory The EOWW Act should be amended to cover Australian Government departments Recommendation 14: Identifying all non-reporting employers A mechanism should be established to ensure that all covered employers are |

|

Targeted effort to close the gender pay gap |

Recommendation 15: Pay Equity as an ‘employment Pay equity should be specified in the EOWW Act as a separate Recommendation 16: National Pay Equity Strategy EOWA should partner with the Commission, acting through the SDC, to jointly

|

|

Special measures to fast track achieving substantive equality in |

Recommendation 17: Targets on Australian Government boards The Australian Government should set a minimum target of 40% of each gender Recommendation 18: ASX Voluntary targets on boards The ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations should be

Recommendation 19: Other ASX ASX companies should consider the following strategies to improve gender

Recommendation 20: Gender quotas after five years if The strategy to improve gender equality at senior levels of business has

The Australian Government should |

|

Associated reforms |

Recommendation 21: Implementing the recommendations of the SDA Review The Australian Government should implement the recommendations of the 2008 Report of Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs

Recommendation 22: Coordinating action between the The FWA/Ombudsman should be required to notify the EOWA and SDC/Commission

Recommendation 23: Reporting of Data by the The FWA/Ombudsman should be required to report annually to the |

4 Diagrams of proposed

national gender equality monitoring and employer compliance frameworks

4.1 National gender

equality monitoring framework

4.2 Employer

Compliance Framework

5 Identifying the

problem: is there gender equality in Australian workplaces?

This section is for Information.

It explains that gender inequality in the workplace remains a major

national problem.

The section provides an overview of the ways in which women experience

gender inequality in paid work. For example:

- Australia is ranked 1st on women’s educational attainment

but only 50th for women’s workforce participation; - Women are only paid 83% of the pay of men for work of comparable value

(based on ordinary full-time earnings); - Women hold only 8.3% of Board Directorships, 2% of CEO Roles, 10.7% of

Senior Executive Positions and 5.9% of Executive Line Management Positions; - 22% of women (compared to 5% of men) have experienced sexual harassment at

work; - Almost one in 5 pregnant women experience difficulty in their workplace

linked to their pregnancy; - Women continue to do the vast majority of unpaid work, even when they are

also in paid work; and - Women accumulate only half the retirement savings of men over their

lifetime.

5.1 Introduction:

findings of the Listening Tour

-

In 2007, Elizabeth Broderick was appointed as the new federal SDC at the

Commission. Commissioner Broderick embarked on a national Listening Tour over

the first eight months of her term. The Listening Tour was designed to assess

the current state of gender equality in Australia through hearing the direct

experiences of men and women. -

In July 2008, the SDC released the report setting out her findings from the

Listening Tour, What matters to Australian women and men: Gender equality in

2008.[14] -

The key finding of the Commissioner was that progress in achieving gender

equality in Australia had stalled. [15] -

In particular, the Listening Tour confirmed that women do not yet

enjoy equality in the workplace. Women are still discriminated against in the

workplace both as individuals and as a group. Women’s full and equal

participation is impeded by a range of factors including:-

ongoing direct and indirect discrimination based on sex, pregnancy and

family responsibilities; -

limited availability of quality part-time, particularly at senior

levels; -

gendered assumptions about women’s roles as carers; and

-

a lack of family friendly work policies.

-

-

Many Listening Tour participants brought the SDC’s attention to the

gendered assumptions, attitudes, stereotypes and discrimination that contribute

to women’s inequality. One woman spoke of her battle to gain a promotion

in a male-dominated industry:I was overlooked for a position which

I knew I had the skills and experience for. When I asked about it, management

said, “That would never happen - she is a female”. I asked Human

Resources what avenues I had and they said, “If you want to keep working

there you should keep your mouth

shut”.[16] -

The findings of the Listening Tour about gender inequality in the workplace

are consistent with discrimination complaints lodged under the SDA. In 2008/09

the vast majority of SDA complaints related to employment

(91%).[17] Twenty-two percent of

complaints alleged pregnancy discrimination and 22% of complaints alleged sexual

harassment.[18] -

This section of the Submission sets out the extent to which women experience

substantive inequality in Australian workforces, including in:-

workforce participation;

-

pay equity and starting salaries;

-

management and leadership positions;

-

prevalence of sexual harassment;

-

pregnancy discrimination; and

-

the impact of unpaid work and family and carer

responsibilities.

-

5.2 Women’s

workforce participation

-

Whilst women’s participation in the paid workforce has risen

dramatically in the last three

decades,[19]Australia lags behind

many other developed countries in terms of women’s workforce participation

rates, ranked number 50 by the World Economic

Forum.[20] -

As at August 2008, only 57.8% of all women aged 15 years and over were in

the labour force, making up 45.3% of Australia’s total labour

force.[21] This may be contrasted

with Norway, for example, where 69.7% of women are in the labour

force[22] or New Zealand at

62.1%.[23] The participation rates

of mothers with young children are particularly low when compared with

comparable OECD countries such as Canada, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the

United States.[24] -

Marginalised groups commonly experience additional barriers to participation

in the paid workforce. Women with

disability,[25] Indigenous

women[26] and women from culturally

and linguistically diverse backgrounds have lower rates of paid workforce

participation compared to the female

average.[27] The additional barriers

experienced by these groups include the non-recognition of overseas

qualifications, discrimination based on race and disability and limited

employment opportunities in rural and remote communities.

5.3 Pay

equity and starting salaries

-

The gender pay gap in Australia persists and is evidence of ongoing

discrimination against women in the workplace. The gap in ordinary full time

earnings between women and men is 17.2% as at February

2009.[28] The gender pay gap is even

greater when women’s part-time and casual earnings are considered, with

women earning around two thirds of the amount earned by

men.[29] Further, women are more

likely to be working under minimum employment conditions and be engaged in low

paid, casual and part time work.[30] Australian women are overrepresented in low paid occupations and industries with

high levels of part time work such as retail, hospitality and personal

services.[31] -

Graduate Careers Australia’s annual Australian Graduate Survey details the average starting salaries of both male and female graduates. The

data shows that the gender pay gap begins as soon as women enter the workforce.

In 2008, new male graduates earned median starting salaries of $47,000 compared

to $45,000 for women.[32] Between

1999 and 2005 there was positive trend with women’s salaries increasing

from 92.3% to 97.5%. In 2006, women’s salaries dropped to 95.2% and

further still to 93.3% in 2007. There was a slight recovery in 2008 when

women’s salaries increased to 95.7% of their male

counterparts.[33] -

The gender pay gap is particularly pronounced in ASX200 companies. Among

the population of key management personnel for whom remuneration data was

available, female median remuneration is shows a gender pay gap of 28.3% which

is 11.1% higher than the national average gender pay

gap.[34]

5.4 Women

in management and leadership positions

-

Despite women constituting 45% of the total workforce in Australia, women

are underrepresented in leadership and management positions in virtually all

sectors of the paid workforce, including the public service, academia,

corporations and boards. -

[Public Service] Women comprise 57.6% of Commonwealth Public Service

employees. Women outnumber men at all junior classifications in the Commonwealth

Public Service but are under-represented at higher classifications. The gap in

women’s participation increases with seniority with women comprising 45%

of Executive Level employees and only 37% of the Senior Executive

Service.[35] -

[Academia] While women account for approximately 50% of lecturing

staff in Australian universities, their numbers decrease significantly with

seniority. Women account for 39% of senior lecturing staff and only 24.5% of

academic staff above senior lecturer. At the University of Sydney, for example,

only 14.5% the academic staff at professorial level and above are

women.[36] The majority of women in

the tertiary education sector can be found at the non academic

classifications.[37] -

[Corporate] The representation of women in executive manager

positions in ASX200 companies has decreased since the 2006 Australian Census

of Women in Leadership when 12% of Executive Managers were women and has

further regressed below the standard set in 2004 when 11.4% of Executive

Managers were women. [38] Women hold

only 2% of Chief Executive Officer Positions and 10.7% of Executive Manager

Positions. [39] -

There are also signs that this downward trend is likely to continue and

possibly worsen in the coming years as the already low number of women in feeder

positions to top leadership appointments decreases. Experience in line

management positions is considered essential for progressing to top corporate

positions. In 2008, women held 5.9% of the Line Executive Management positions.

This was a decrease from 7.5% in

2006.[40] A female participant in

the Listening Tour pointed out the disparity in what employers say and what they

do in terms of promoting women’s leadership:[Our CEO] has

publicly said he would have 50 per cent women in his work force if he could.

But then he also... set up an executive structure that is going to hinder his

ability to get women into those senior positions by setting meeting times that

women with caring responsibilities won’t be able to

attend.[41] -

The majority of women who make it into executive management roles in ASX200

companies are still clustered in support roles where they are responsible for

supporting main business functions (including Human Resources, Legal, Public

Relations) rather than line management roles (which hold responsibility for

profit and loss or direct client

service).[42] -

Female executive managers are far less likely to be classified as line

managers than male executive managers. Only 39.6% of female executive managers

are considered line managers (the remaining 60.4% of female managers are

considered support managers).[43] By

comparison, the majority of male executive managers (75.3%) are line managers

(with the remaining 24.7% of male managers classified as support

managers).[44] -

[Women on Boards] EOWA’s 2008 Census of Australian

Women’s Leadership in ASX200 companies revealed women chair only 2% of

ASX200 companies (that is four boards) and hold only 8.3% of board

directorships. While there has been an overall increase in the total number of

board positions since 2006, the number of these seats held by women has not kept

up at the same pace.[45] While two

years ago 12% of ASX200 companies boasted more than 25% of their board directors

were women, in 2008 this number has halved to

6%.[46] This data represents a

comprehensive decline since

2006.[47] -

This compares with 14.8% in the United States, 14.3% in South Africa, 11% in

the UK, 10.2% in Canada and 8.7% in New Zealand. [48] -

While 54.5% of ASX200 companies have at least one woman in an executive

management position, again this rate is lower than international comparators. In

the US 85.2% of top companies have at least one woman in executive management

positions as do 65.6% of Canadian companies, 60% in the UK and 59.3% in South

Africa.[49] This is a dramatic

change from the 2006 Census when Australia was outperformed only by the US. -

The representation of women on Government appointed boards and committees is

higher than that of the private sector but still not representative of

women’s interests or ability. The OFW reports that as at 30 June 2008,

women comprise 33% of the total membership of Australian Government boards and

bodies and 22% of Chair or Deputy Chair

positions.[50] There is a higher

representation of women on boards where the Australian Government has total

control over the appointments. [51] However, the percentage of women on Government appointed boards varies

significantly across departments. In 2006, just over half of the members of

Government boards and bodies in the Department of Families, Housing, Community

Services and Indigenous Affairs were women. Government boards and bodies in the

Departments of Immigration and Multicultural

Affairs,[52] Health and Ageing and

Human Services also had high rates of women’s participation (over

40%).[53] The Departments of

Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry; Defence and Finance and Administration had

the lowest rate of women’s representation on Government boards and bodies

(less than 20%).[54]

5.5 Prevalence of

sexual harassment

-

The continuing presence of sexual harassment is a key marker of gender

inequality in the workplace and one reason women do not progress. In 2008, the

Commission conducted a national telephone survey to investigate the nature and

extent of sexual harassment in Australian workplaces. The survey found that 22%

of women and 5% of men aged 18-64 have experienced sexual harassment in the

workplace in their lifetime.[55] While this was a slight decrease from the results of the same telephone survey

in 2003, what was concerning was the lack of understanding about what sexual

harassment is. Around one in five (22%) respondents who said they had not

experienced ‘sexual

harassment’[56] then went on to report having experienced behaviours that may in fact amount to

sexual harassment under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth). [57] -

Sexual harassment occurs across all sizes of employer. The 2008 Survey

reported that for those who experienced sexual harassment in the last five

years, there was an even spread of employer size: 39% large employers, 30%

medium employers and 31% small employers. [58] The top three industries identified

by respondents who experienced sexual harassment in the last five years were:

health and community services (14%), education (12%) and accommodation, cafes

and restaurants (10%). -

During the Listening Tour a female focus group participant shared with the

SDC her comments on the constant self surveillance that women become accustomed

to:You wear a sack to not show yourself off, you talk to the safe

people who you know [at work]. You are constantly thinking about your

gender.[59] -

Over the course of the Listening Tour there was a feeling that sexual

harassment was almost impossible to eradicate. On this point, one woman

recounted her experience of hearing her colleague talk about a woman in a

degrading manner:I don’t think there’s any

organisation that’s ever going to be able to put their hand on their heart

and say, “We are free of sexual harassment in the workplace”. I was

absolutely astounded a few weeks ago now. I was having a cup of coffee with a

colleague and one of them had actually participated in a selection panel

recently and I literally spat my coffee out because they were talking about one

of the females that they had interviewed. This guy just turned around and said,

“and she had the best set of

tits”.[60] -

A similar sentiment highlighting the pervasive and persistent nature of

sexual harassment was expressed by a contributor to the blog:I was

recently sexually harassed by the boss at a work [Christmas] function and the

company have since tried to sweep everything under the carpet. I have been left

feeling very vulnerable and anxious. Whilst also feeling isolated by the

management and workers.[61] - Nearly one in five complaints received by the Commission under the SDA

relate to sexual harassment.[62] The

vast majority of these take place in the workplace. However, the

Commission’s survey found that overall, the number of people who have

formally reported or made a complaint after experiencing sexual harassment

significantly decreased between 2003 and

2008.[63] In 2008, only 16% of those

who have been sexually harassed in the last five years in the workplace formally

reported or made a complaint, compared to 32% in 2003. For those who did not

make a complaint:- 43% did not think it was serious enough;

- 15% were fearful of a negative impact on themselves;

- 21% had a lack of faith in the complaint process; and

- 29% took care of the problem themselves.

-

In 2008, a total of 22% of respondents who made a formal complaint reported

that the outcome of their complaint resulted in a negative impact on them. The

negative impacts include the person who experienced the harassment being

transferred or changed shifts, resigning, being dismissed, demoted or

disciplined or were laughed at and ostracised. During the Listening Tour, an

employer confirmed that most women will attempt to deal with sexual harassment

informally or leave the workplace because of this fear of

victimisation:It absolutely still is an issue and people have a

fear of making a complaint because it is a career killer. You try and deal with

it informally or you just get

out.[64]

5.6 Pregnancy

discrimination in the workplace

-

Pregnancy is a time when women are commonly vulnerable to discrimination and

inequality in the paid workforce. This can take the form of demotions, missing

out on promotions, redundancies, denial of family friendly conditions and even

bullying in some cases.[65] Almost

one in every five pregnant working women experiences at least one difficulty in

their workplace in relation to being

pregnant.[66] Over one in five of

the complaints received by the Commission under the SDA were complaints of

pregnancy discrimination.[67] As

such, this point in the lifecycle has a significant impact on participation in

the paid workforce and level of earnings. Accordingly, when superannuation

balances are broken down by age, the largest widening of the gender gap occurs

between the 23-34 and 35-44 age brackets, coinciding with the time when women

commonly have children.[68] -

A Listening Tour participant described the experience of her

daughter-in-law, which highlighted how discrimination following pregnancy can

impact upon women’s labour market participation:I have a

daughter-in-law who works for a call centre. She fell pregnant and had a baby.

At this time her boss said that if she wanted to come back she could. After six

months, he gave her a hard time and said she had to work full time if she wanted

to work. He did this because he thought women should be in the home. She ended

up leaving. She knew it was discrimination but he is the

boss.[69] -

Women do not even have to be pregnant to experience this disadvantage. On

the Listening Tour, one woman reported her experience of workplace

discrimination on the grounds of potential pregnancy:I’ve had

a comment about me that I shouldn’t be given a permanent job because I may

have a baby soon. I’m not even

pregnant.[70] -

The vulnerability of women’s employment, including potential job

losses, demotions and redundancies, arising at the time of pregnancy or

returning to work following pregnancy, can have severe consequences to

women’s financial security and career progression. -

During the Listening Tour, many women commented on the difficulty of

re-entering the paid workforce after a break to care for children. Issues raised

included the availability of work at the same level, control over the hours of

work, lack of family friendly workplace policies and the need for skills

development.

5.7 Impact of unpaid

work and family and carer responsibilities

-

Perhaps the most fundamental barrier to women’s full participation in

paid work is the struggle to balance paid work with unpaid labour, including

family and carer responsibilities. -

Women continue to undertake the large majority of unpaid work in households,

including caring for children and other domestic

work.[71]The birth of children is a

key point in the lifecycle where gender inequality in the division of unpaid

work commonly widens.[72] ‘Time use’ studies show that the birth of a child commonly

leads to mothers not only doing less paid work and more of the unpaid work of

child care, but also the extra tidying, shopping, cleaning and laundry that the

presence of children creates. The birth of a child results in women working

incredibly long hours in both paid and unpaid work. In 2006, the total hours of

work for mothers whose youngest child was between 0-4 was 85.9 hours weekly,

compared to 79.6 hours for fathers, 61.3 hours for men without children and 55.5

hours for women without

children.[73] -

The gap between women and men’s earnings may also influence decisions

about who undertakes paid and unpaid work in a

household.[74] The gender pay gap

may, in effect, force the higher earner to take on the majority of paid work

while the lower earner, usually female, commonly takes on the majority of the

unpaid caring work and in many cases reduces her participation in the paid

workforce. During the Listening Tour one man recounted his own experience of

this decision:Doing the sums of child care can make it more

economical for my wife to stay at home because she earns less than I do. [75] -

One service provider noted that closing the gender pay gap is critical for

creating an environment where men can undertake greater caring

responsibilities:More and more blokes want to care for their

children, but financially they are not making that decision because men are

earning more. They are the breadwinners. If you do equalise women and

men’s pay it will create opportunities for men to do

that.[76]

5.8 Gendered

ageism

-

Older women face particular barriers to paid workforce participation due to

‘gendered ageism’,[77] where gender discrimination is exacerbated by age

discrimination.[78] Age

discrimination creates barriers to paid workforce participation in re-entry to

the paid workforce, recruitment, training, promotion, terms and conditions of

employment, the balancing of unpaid work and phased retirement. -

One way gendered ageism manifests is in the use of unlawful stereotypes and

assumptions about older women workers. Such stereotypes include being perceived

as ‘loyal but lacking potential’, ‘low in energy’ and

‘unwilling to accept

criticism’.[79] Employers may

also assume that all older female workers will have had significant breaks in

their employment due to family responsibilities and will not possess the skills

required for the position.[80] -

The consequences of discriminatory stereotyping for older women are

far-reaching and serious. Research has shown that these stereotypes and

assumptions can prevent older women from being selected for jobs or, when

employed, from being considered for training and promotion

opportunities.[81] This has obvious

consequences for older women in light of appointments to boards and access to

leadership positions more generally, despite being highly qualified for such

positions. -

In the face of entrenched discrimination, older women themselves can start

to believe and internalise these stereotypes and select out of work and

promotion opportunities. This represents a serious leakage of talent and skills

in terms of the potential leadership pool and for the Australian labour force as

a whole.

5.9 Conclusion

-

It is clear that on a range of key indicators of gender inequality in

Australian workplaces, including workforce participation rates, pay rates,

representation in leadership positions, and experiences of sexual harassment and

discrimination, women experience substantive inequality in comparison to their

male counterparts. -

As the next section explains, gender inequality in the Australian workforce

matters to individuals and the entire community. It impacts harshly on

individual women, has flow on effects to families, impacts negatively on

businesses and national productivity. It also undermines our fulfillment of

international human rights and labour rights.

6 The case for reform:

why does achieving gender equality in Australian workplaces matter?

This section is for Information.

It sets out why achieving gender equality in the workplace matters, and the

range of benefits that will be delivered.

It explains that achieving gender equality in Australian workplaces will:

- improve economic security for women;

- be better for business and other organisations;

- improve national productivity; and

- fulfill our international human rights and labour rights

obligations.

6.1 Introduction

-

Achieving gender equality in Australian workplaces represents both a

significant challenge and a significant opportunity. Australia faces a number of

well documented economic and social challenges over the coming years. Chief

amongst these challenges is realizing the full potential of our workforce in the

context of an ageing population. -

The three P’s of economic growth – population, participation and

productivity - are the levers that will assist us to meet these challenges and

increase prosperity. -

The under-employment of women is a setback to productivity and participation

and detracts from economic performance. It also negatively impacts on women and

men, and their children. -

In summary:

-

Greater gender equality in employment will improve women’s economic

security, and fulfill our international human rights and labour rights

obligations; -

Greater equality in women and men’s workforce participation will have

a major impact on national productivity; -

Greater diversity including gender diversity at the senior leadership and

board level will increase corporate performance; -

Businesses will be able to draw on a wider talent pool. With demographic

change and an impending skills shortage, having access to the full talent pool

including currently under-utilised talent pools is vital; -

Greater gender balance at the most senior levels within companies will

result in decisions that are more in touch with customer and client needs and

more representative of the consumer base many companies rely

upon.

-

-

Gender equality in Australian workplaces must be seen in a broader social

context. The issue of the absence of women on corporate boards or at senior

leadership level is not one which threatens basic human requirements like

housing, food and safety. However, there is a strong connection between how

women are treated in corporate and business life and how women are treated

everywhere else across Australia. The statistics on women’s leadership

reflect our progress towards gender equality, as do statistics on violence

against women, sexual harassment, pay equity and retirement savings. As Irene

Lang, President of Catalyst recently said:‘Until women are

equitably represented in leadership in the private, economic sector, they will

be marginalised in every other

arena.’[82] -

This section sets out in further detail the case for reform to achieve

gender equality in the workforce. It highlights the benefits to women, and to

fulfilling our international human rights and labour rights obligations. -

Importantly, gender equality in the workforce will also have a major impact

on national productivity, be better for business and employers.

6.2 Gender equality

will improve women’s economic security

-

The net result of gender inequality for a woman in her experience of paid

work is a major gap in the overall economic security for women in comparison to

men. -

Overall, women earn an average of approximately 83 cents to the male

dollar[83] and typically experience

lower economic and financial security at all stages of the

lifecycle.[84] -

A recent Australian study showed that, overall, a 25-year-old man is likely

to earn a total of $2.4 million in their lifetime, which is more than

one-and-a-half times the $1.5 million prospective earnings of a woman. Men who

have a bachelor degree or higher and have children will earn around $3.3 million

over their working life which is nearly double the $1.8 million that their

female counterparts can expect to

earn.[85] -

Women make up 73% of all the recipients of the single rate of the Age

Pension[86] and single elderly

female households not only experience the highest incidence of poverty compared

to other household types[87], but

are also at the greatest risk of persistent

poverty.[88] -

The extent to which women do not enjoy economic security on an equal basis

with men is most starkly demonstrated by the gender gap in retirement

savings. -

In September 2009, Commissioner Broderick released a major Issues Paper,

‘Accumulating Poverty?: Women’s experiences of inequality over the

lifecycle.’ The Issues Paper highlights that:Superannuation

balances and payouts for women are approximately half of those of men. Future

projections show that the gap will remain a problem for coming generations. The

gap has serious implications for women, particularly the likelihood of sole

reliance on the Age Pension and subsequently, an acute vulnerability to poverty

in retirement.[89] -

The Issues Paper concludes that

[i]ncreasing women’s

labour market participation and increasing women’s earnings across the

lifecycle is critical to closing the gender gap in retirement savings. Measures

to support women’s labour market participation and address the gender pay

gap must feature as a strategy to build women’s financial security [across

the lifecycle and] in

retirement.[90] -

A range of measures are needed to ensure that women enjoy an adequate

standard of living, including social security benefits to provide an adequate

safety net, and placing financial value on unpaid caring

work.[91] -

However, promoting gender equality in Australian workplaces has significant

potential for ensuring that women enjoy economic security on an equal basis with

men. Enabling all people, regardless of gender, to engage in paid work, with

appropriate financial compensation, is a key area in need of law and policy

reform.

6.3 Gender equality

will improve business and organisational performance

- Achieving gender equality in the paid workforce is also important for strong

business performance. There are several ways in which greater gender diversity

impacts positively on business outcomes. These include halting the leakage of

female talent from workplaces, appealing to women as consumers and improving

business performance.

-

Talent is absolutely critical for all corporations. An ability to draw on

the widest possible talent pool delivers a competitive edge. Along with

investment and technology, people are the essential ingredient for increasing an

individual business’ bottom line. Recruitment and retention of talented

women represents a major opportunity for businesses. At present,

companies in the ASX200 are not accessing the full spectrum of available talent.

Fifty one percent of ASX200 companies have no women directors and 45.5% of

ASX200 companies have no women at all on their executive

teams.[92] The pipeline of

women to the next most senior level is also small. Chief Executive Women (CEW)

has projected that on the current trajectory it will take over 150 years for

women to hold a similar number of senior positions as

men.[93] -

With 55.9% of graduates from Australian Universities being

female,[94] it makes no sense that

only 5.9% of senior line management roles in ASX 200 companies are held by

women[95] or that only 8.3% of Board

positions are held by women.[96] It

is clear that without significant intervention we will not stem this leakage of

female talent.

-

In Australia, women exercise strong consumer power. Organisations with a

balance of men and women at the senior levels tend to consider a wider range of

options, resulting in decisions that are more in touch with customer needs. It

has been estimated that women handle about 75% of family finances and influence

about 80% of buying decisions.[97] Therefore products and services that appeal to women have a good chance of

success. -

It makes sound business sense to include women at all levels of

decision-making in organisations to broadly represent, and provide unique

insights into, this significant customer base.

-

There have been a number of research studies looking at the impact of

women’s decision-making on corporate performance. -

International research indicates companies with a higher proportion of women

in their boards and top management team have better financial

performance.[98] This and other

corporate research suggest that organisations with better gender balance are

able to avail themselves of a broader talent pool value and leverage the skills

and contributions of all

employees.[99] In addition,

diversity in the workforce, including gender diversity, increases overall

employee engagement and

productivity.[100] -

Research undertaken by Catalyst in 2007 to investigate the return on equity

in Fortune 500 Companies found that those companies with the most female board

directors outperformed those with the least by

53%.[101] -

Recent research undertaken by Chicago-based Hedge Fund Research found that

hedge funds run by women have fallen only half as much in the financial crisis

as those managed by men.[102] This

research showed the value of female-managed funds has dropped by 9.6% in the

past year, compared with 19 per cent for the rest. -

Women investment managers also performed better in general over the past

decade, with an average annual return of just over 9%, while hedge funds overall

delivered 5.82%.[103] -

In summary, current research indicates that companies with a critical mass

of women at the top achieve significantly better results.

6.4 Gender equality

will improve national productivity

-

There is an urgent case for achieving gender equality in Australian

workplaces in order to increase Australia’s national productivity. As

noted by the World Economic Forum, ‘there is a strong correlation between

the gender gap and national competitiveness...a nation’s competitiveness

depends significantly on whether and how it educates and utilizes its female

talent.’[104] -

Factors contributing to lower national productivity include:

-

Australia ranks as equal first in the World Economic Forum Gender Gap Index

of women’s educational attainment, yet only 50th in women’s

workforce participation. In other words, the return on our investment in

women’s education is very low. No nation or government, industry or sector

can afford this kind of loss. Without significant intervention – by

government and by business – the number of women progressing in the

workplace may shrink even further. -

Australia’s investment in women’s skills development, is forgone

when many women are working below their skill level, or have retreated from paid

work altogether. Ensuring that women are enjoying gender equality in paid work

is important for Australia’s national productivity in light of the ongoing

skills shortages, despite the global financial crisis in many key

industries. -

Australia faces significant challenges with its ageing population in terms

of its paid workforce ratio over the medium to longer term. By 2050, there will

be a quadrupling of the proportion of people over 85 and a doubling of the

proportion of people over 65.[105] Addressing the barriers to women’s participation in paid work would

significantly improve the paid workforce ratio over time which is essential to

expanding the nation’s tax base. -

Women’s reduced ability to achieve a level of economic security

through paid work leads to a reduced ability to fund their own retirement. As

noted above, women currently hold only half the retirement savings of men, and

make up 73% of single Age Pension

recipients.[106] Improving

women’s attachment to the labour market will alleviate pressures on our

social security system.

-

-

It is vital to national productivity that all people in Australia who want

to be in paid work are able to do so to the maximum of their skills, abilities,

and aspirations, regardless of gender.

6.5 Gender equality

will fulfil Australia’s international human rights and labour rights

obligations

-

Achieving gender equality in paid work is crucial to ensuring economic

security for women on an equal basis with men. It is also an international human

rights and labour rights obligation of the Australian Government. -

The Australian Government’s international human rights and labour

rights obligations relevant to the issue of gender equality in the workforce are

set out in the following international instruments:-

The Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against

Women (CEDAW) -

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

-

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

(ICESR) -

International Labour Organisation Conventions 111, 100 and 156

-

Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action

-

-

These international agreements impose a clear obligation on the Australian

government to achieve substantive gender equality in Australian workplaces. -

For example, CEDAW places an obligation on the Australian Government

to:take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination

against women in the field of employment in order to ensure, on a basis of

equality of men and women, the same rights, in particular... the right to the

same employment opportunities...the right to promotion...[and] equal

remuneration.[107] -

Article 2 imposes an obligation on Australia to prevent discrimination

against women in all sectors and CEDAW stipulates a range of appropriate

measures must be taken, “including legislation, to modify or abolish

existing laws, regulations, customs and practices which constitute

discrimination against

women.”[108] -

Similarly, as a signatory to the ICESCR, the Australian Government has an

obligation to:recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of

just and favourable conditions of work which ensure, in particular... Equal

opportunity for everyone to be promoted in his employment to an appropriate

higher level, subject to no considerations other than those of seniority and

competence.[109] -

Australia is party to a number of international ILO Conventions which impose

obligations to pursue gender equality in areas related to employment and

occupation and eliminate discrimination in the workplace on the basis of sex

and/or family responsibilities. -

For further detail of Australia’s international human and labour

rights obligations, see Appendix 1. -

The data available on gender equality in the workforce, set out in section 5

of this Submission suggests that Australia is not currently meeting its

international human rights and labour rights obligations in this area.

Special measures to achieve

gender equality

-

It is clear that Australia is obliged to take action to eliminate

discrimination between men and women in the workplace. One of the arguments

against taking action aimed at advancing opportunities for women in the

workplace, such as quotas and targets, is that such action may constitute

discrimination against men. -

However, it is clear that taking temporary special measures aimed at

accelerating the de facto equality between men and women is not discrimination

at international law. Article 4 of CEDAW provides:1. Adoption by

States Parties of temporary special measures aimed at accelerating de facto

equality between men and women shall not be considered discrimination as defined

in the present Convention, but shall in no way entail as a consequence the

maintenance of unequal or separate standards; these measures shall be

discontinued when the objectives of equality of opportunity and treatment have

been achieved.2. Adoption by States Parties of special measures, including those measures

contained in the present Convention, aimed at protecting maternity shall not be

considered discriminatory.[110] -

A similar definition is used in the

SDA.[111] -

In order to achieve genuine equality in practice, any definition of

discrimination must allow for special measures. Special measures permit acts and

practices that will ultimately further the goal of gender equality. Without

them, a simple ‘sameness of treatment’ approach can prevail, that

will give a surface appearance of equality, but has the potential to undermine

equality of outcome. -

According to the CEDAW Committee, the purpose of art 4(1) is to accelerate

the improvement of the position of women to achieve their de facto or

substantive equality with men, and to effect the structural, social and cultural

changes necessary to correct past and current forms and effects of

discrimination against

women.[112] -

The CEDAW Committee views special measures as being more than simply actions

taken on a ‘good faith’ basis to achieve a particular purpose. The

meaning of ‘special’ refers to the fact that the measures are

designed to serve a specific

goal.[113] Therefore, the measures

must be designed, applied and evaluated against the background of the specific

nature of the problem that they are intended to

address.[114] -

The CEDAW Committee recommends States parties ‘evaluate the potential

impact of temporary special measures with regard to a particular goal within

their national context. State parties should then adopt those temporary special

measures which they consider to be appropriate in order to accelerate the

achievement of de facto or substantive equality for

women.’[115] -

The adoption and implementation of temporary special measures may raise

issues of the qualifications and merit of the group or individuals so targeted.

On this issue the CEDAW Committee has commented that:as temporary

special measures aim at accelerating achievement of de facto or substantive

equality, questions of qualification and merit, in particular in the area of

employment in the public and private sectors, need to be reviewed carefully for

gender bias as they are normatively and culturally

determined.[116] -

The duration of a temporary special measure should be determined by its

functional result in response to a concrete problem and not by a predetermined

passage of time. Temporary special measures must be discontinued when their

desired results have been achieved and sustained for a period of

time.[117] -

Further, the CEDAW Committee recommends that States parties ensure that

women in general, and affected groups of women in particular, have a role in the

design, implementation and evaluation of special measures programs. In

particular, collaboration and consultation with civil society and

non-governmental organisations representing various groups of women is

especially recommended.[118] -

This submission includes recommendations for the adoption of special

measures to fast track substantive equality outcomes for women in leadership

roles. See section 8.9.

7 The

current context: what are the national laws and institutional

arrangements?

This section is for Information. It describes the three main

national laws that regulate gender equality in the Australian workforce:

- Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Act 1999 (EOWW Act)

- Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (SDA)

- Fair Work Act 2009 (FWA)

The section also provides an

overview of the three corresponding responsible authorities set up under each

statutory scheme:

- The Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Agency (EOWA)

- The SDC and the Australian Human Rights Commission (SDC/Commission)

- The Fair Work Ombudsman and Fair Work Australia

(FWA/Ombudsman)

It explains that the EOWW Act and Agency are

gender specific and have an emphasis on employer capacity building, monitoring

and reporting.

The Commission has gender specific functions, has the statutory position of

SDC, uses an equality/anti-discrimination framework and has an emphasis on

complaint handling, policy development and advocacy, education and independent

monitoring with some systemic powers.

The FWA/Ombudsman is a generalist industrial relations system and has an

emphasis on complaint handling with strong systemic enforcement powers.

7.1 Introduction

- This section of the Submission provides an overview of the current

regulatory environment that most directly impacts on gender equality in the

workforce. It sets out the three major pieces of legislation, and their

institutional arrangements, and provides a Table at section 7.4 which contains

key features of each of the three statutory schemes. It concludes that there is

currently a lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities amongst the three

statutory schemes, particularly for action to drive systemic reform to achieve

gender equality in Australian workplaces. The lead roles of each of the gender

equality statutory scheme should be clarified, including the role of EOWA. In

addition, the links between the statutory schemes should be strengthened and

formalised.

7.2 National laws

impacting on gender equality in the workforce

-

At the national level, there are three main laws that regulate gender

equality in the workplace:-

Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Act 1999 (EOWW Act).

-

Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (SDA); and

-

Fair Work Act 2009 (FWA).

-

-

Each of the states and territories also has anti-discrimination legislation

that includes gender as a protected

attribute.[119] The State and

Territory anti-discrimination Acts also prohibit direct and indirect

discrimination in the workplace and operate concurrently with both the

SDA[120] and the

FWA.[121] -

It should be noted that a comparable scheme to the EOWW Act regulates

Federal public sector employment. Employees of government departments are

covered by the Public Service Act

1999[122] and employees of

statutory authorities are covered by the Equal Employment Opportunity

(Commonwealth Authorities) Act 1987. Also, a number of states have their own

equal employment opportunity legislation for public sector

employment.[123] -

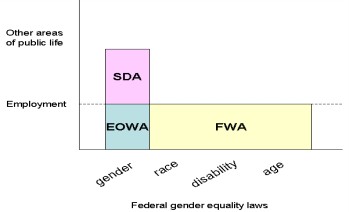

The above three national Acts vary in terms of how they regulate equality,

the scope of the attributes and areas of public life they cover, as well as

their enforcement mechanisms. -

The diagram that follows represents the intersection of attributes and areas

of each of the main national gender equality Acts.

-

The EOWW Act is uniquely targeted at tackling systemic sex discrimination in

business and employer organisations. It aims to encourage employers to take

action to achieve equal opportunity for women in the workplace. However, it has

limited coverage[124] and weak

enforcement powers.[125] -

The SDA generally prohibits direct and indirect discrimination on the ground

of sex and related attributes across many prescribed areas of public life, one

of which is employment. The SDA is primarily enforced through an individual

complaint process. However, it also gives the Commission some functions that can

be used to challenge systemic

discrimination.[126] -

The FWA regulates federal workplace relations generally including adverse

action on the basis of many prohibited attributes, one of which is sex, and

creates the strongest enforcement powers.

7.3 Institutional

arrangements under national laws impacting on gender equality in the workforce

-

Each of the main national laws that impacts on gender equality in the

workplace – the EOWW Act, SDA and FWA - establish responsible institutions

that play an important role in achieving gender equality in Australia. In

addition, the Australian Government Office for Work and Family, Office for Women

and the Prime Minister’s Women’s Advisor all play a role. -

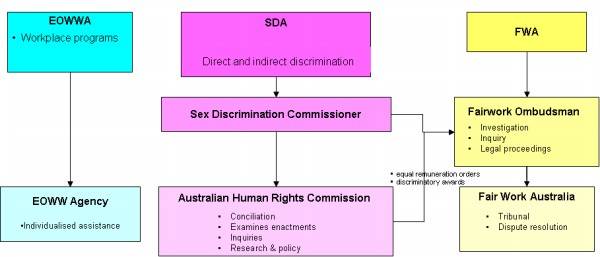

In summary, the EOWA, the SDC/Commission and FWA/Ombudsman are all empowered

to challenge systemic discrimination against women. However, only the EOWA has

dedicated resources to spend on assisting employers to take positive action to

achieve gender equality in the workplace. The SDC/Commission have an established

role in monitoring and advocating for gender equality, including gender equality

in employment, and both the SDC/Commission and the FWA/Ombudsman have individual

complaint handling functions. -

The SDC/Commission have some legislative functions that can be used to

address systemic discrimination which relate to all manifestations of gender

inequality across all areas of public life and not solely employment. -

While the FWA/Ombudsman functions and powers are far reaching and focused on

the area of employment, unlike the SDC/Commission, the FWA/Ombudsman are

concerned with a broad range of industrial matters across a wide range of

industries. The FWA/Ombudsman are not specialist gender or discrimination or

conciliation institutions. -

Further details of each of the national laws and institutional arrangements

regulating gender equality in Australian workplaces is provided in Appendix

2. -

A summary of the key features of each statutory scheme is set out below.

7.4 Table comparing

Australia’s gender equality laws & institutions

| |

SDA | EOWW Act | FWA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attributes |

|

|

|

| Area |

|

|

|

| Coverage |

|

|

|

| Operative provisions |

|

|

|

| Enforcement |

|

|

|

| Institutions and their functions |

|

|

|

7.5 Relationship and