CERD Index

Information concerning Australia and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

Submission by the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission

Click on the links below to also access:

- Information Note

- Australian NGO submission for the 13th and 14th session of the Committee

- Concluding observations of the Committee on AUSTRALIA

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Homepage

- Race Discrimination Homepage

7 January 2005

This submission is prepared by Australia's national human rights institution, the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC). It provides information in relation to the Australian Government's combined 13th and 14th periodic report under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD). All of the material contained in this document has previously been brought to the attention of the Australian government through a range of Commission publications and submissions.

Table of Contents

The submission contains information about the following issues.

Section 1: General measures of implementation - the role of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission and the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth)

Section 2: Issues relating to Indigenous peoples (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples)

Section 3: Issues relating to migrants, asylum seekers and minorities

|

Issue

|

Description

|

|---|---|

| 13 | Ismaع - Listen: National consultations on eliminating prejudice against Arab and Muslim Australians |

| 14 | Government Services for Migrant and Refugee Settlement |

Each section of the submission commences with a summary box which provides an overview of the issue, its relevance to ICERD and a link to where the issue is discussed in Australia's periodic report. The submission also provides internet links to further information which may be of interest to the Committee.

Acronyms

The following acronyms are used throughout the submission.

ATSIC: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission

ATSIS: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services

COAG: Council of Australian Governments

HREOC: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission

HREOC Act: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Act 1986 (Cth)

ICERD: International Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination (1965)

NTA: Native Title Act 1993 (Cth)

RCIADIC: Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (1991)

RDA: Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth)

Section 1: General measures of implementation - the role of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission and the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth)

1. Introduction

Summary of issue

This section provides an overview of the role of HREOC. The Commission is Australia's national human rights institution and has the following functions to implement or monitor Australia's compliance with ICERD:

- conciliating individual complaints of racial discrimination;

- assisting courts in discrimination matters (as 'amicus curie');

- intervening in court cases in which human rights issues are raised;

- specific functions of the Race Discrimination Commissioner to promote compliance with the RDA and ICERD;

- specific functions of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner to promote compliance with human rights principles for Indigenous peoples; and

- education functions to promote awareness and understanding relating to human rights and racial discrimination.

Relevance to ICERD

- Articles 2, 5, 6 and 7

Where the issue is discussed in Australia's 13th and 14th periodic report

Paragraphs 6-13

HREOC is Australia's national human rights institution. It is established by a law of the federal Parliament, the HREOC Act. HREOC operates in compliance with the Principles for national institutions for the promotion and protection of human rights (the 'Paris Principles') as approved by the United Nations General Assembly.(1)

The HREOC Act provides for the Commission to consist of six members - a President and five Commissioners. The Commissioners are designated as follows: a Human Rights Commissioner, Race Discrimination Commissioner, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Sex Discrimination Commissioner and Disability Discrimination Commissioner. In 2004, HREOC has also been provided with functions to implement newly introduced age discrimination legislation.

The five Commissioner positions are held by three people. Since 1999, the positions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner and Race Discrimination Commissioner have been held by the one person.

HREOC has the following specific functions which implement or monitor Australia's obligations under ICERD:

- Conciliation of individual complaints: HREOC attempts to conciliate complaints of racial discrimination and racial vilification brought under the RDA. Complaints that cannot be resolved through conciliation are terminated and may then be taken to the courts for determination.

- Amicus curiae role: Where a complaint has been lodged with the courts, HREOC Commissioners may seek the leave of the court to provide assistance on the interpretation of discrimination law as a friend of the court ('amicus curie'). This includes advising on the interpretation of Australia's obligations under ICERD or its domestic implementation through the RDA.

- Legal intervener role: HREOC may seek leave to intervene in matters before the courts that relate to its mandate. To date HREOC has intervened in over 40 matters before the courts. These matters include some in which the provisions of ICERD and the RDA have been relevant, such as the interpretation of the race power in section 51(xxvi) of the Commonwealth Constitution;(2) and the consideration and application of native title principles.(3)

- Race Discrimination Commissioner: The Race Discrimination Commissioner has specific roles to promote and monitor compliance with the RDA. This includes promoting research and educational programs that combat racism and fostering awareness of and compliance with federal race discrimination and racial vilification legislation.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner: The Commissioner has an independent monitoring role on the impact of government activity on the exercise and enjoyment of human rights by Australia's Indigenous peoples. The Commissioner reports annually to the federal Parliament on the status of enjoyment of Indigenous human rights (the Social Justice Report) and the impact of native title legislation on the enjoyment of Indigenous human rights (the Native Title Report). The Commissioner also has functions to examine the impact of proposed or actual legislation on the enjoyment of Indigenous peoples' human rights and the conduct of activities to promote respect for enjoyment of human rights by Indigenous peoples.

- Education: HREOC has a role to promote understanding of human rights, as well as specific functions to promote understanding and awareness about racial discrimination.

These roles and functions are discussed further throughout the submission.

2. The Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth)

Summary of issue

The RDA makes it unlawful to directly or indirectly discriminate against a person on the basis of their race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin.

However, under the RDA it has proved difficult for complainants to establish race discrimination in the absence of direct evidence. No cases of racial discrimination (as distinct from racial hatred) have been successfully litigated in the federal court system since 2001.

Relevance to ICERD

- Articles 2, 5 and 6

- General Recommendations VII and XXVI

Where the issue is discussed in Australia's 13th and 14th periodic report

Paragraphs 6-19

The RDA incorporates Australia's obligations under the ICERD into federal law. Section 9(1) of the RDA prohibits direct race discrimination and section 9(1A) prohibits indirect race discrimination against a person on the basis of their 'race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin'. The RDA also includes specific prohibitions on discrimination in the following areas of public life:

- Access to places and facilities;

- Land, housing and other accommodation;

- Provision of goods and services;

- Right to join trade unions; and

- Employment.

Complaints of race discrimination are made to HREOC and the President is responsible for inquiring into and attempting to conciliate the complaint. Since April 2000,(4) where a complaint is terminated the complainant may apply to the Federal Court of Australia or the Federal Magistrates Service to have their allegations heard and determined.

It is difficult for complainants to successfully bring cases about racial discrimination without direct evidence.(5) Since Australia's previous periodic reports under ICERD were considered, five cases have been successfully litigated under the RDA. Each of these cases was brought under the racial hatred provisions of the Act where there was direct evidence (in the form of a published work) on which the court could base its finding of racial hatred.(6) No case has been successfully litigated under the racial discrimination (as opposed to the racial hatred) provisions of the RDA in that period(7).

Although the existence of systemic racism has been routinely acknowledged by decision-makers considering race discrimination, the courts have been reluctant to use the existence of that as a basis on which to draw an inference of racial discrimination. The cases highlight the difficulties faced by complainants in proving racial discrimination in the absence of direct evidence, particularly in the context of decisions about hiring or promotion in employment.

For example, in Sharma v Legal Aid Queensland,(8) a case involving alleged discrimination in recruitment for senior legal positions, the complainant alleged that racially discriminatory conduct could be inferred from 'the known existence of racism' combined with the fact that the decision to appoint people to senior legal positions was 'made between people of different races'.(9) The Federal Court held that it should be wary of 'presuming the existence of racism', but that nonetheless, in some cases, statistical evidence illustrating a high rate of failure of people of a particular racial group may indicate that the real reason for refusal is a conscious or unconscious racial attitude which involves stereotypical assumptions about members of the group.(10) However, this was not such a case.

The decision of the Federal Court in that case was upheld by the Full Federal Court on appeal.(11) The Full Court agreed that in appropriate cases inferences of discrimination might be able to be drawn saying that, 'it may be unusual to find direct evidence of racial discrimination', especially where an employer's motivation not to employ someone is subconscious.(12) However, again, the court reiterated that such inferences are not to be made lightly, reflecting the reluctance of courts to draw inferences of racial discrimination in the absence of direct evidence.(13)

The issue also arose in Tadawan v South Australia,(14) in which the applicant, a Filipino-born teacher of English as a second language alleged victimisation by her employer on the basis of having made a previous complaint of racial discrimination. It was argued that victimisation could be inferred from the decision not to re-employ the applicant on the basis of the applicant's superior qualifications and experience; that the applicant was 'first reserve' for a previous position but was not given any work; that new employees were taken on in preference to providing work to the applicant; and the lack of cogent reasons for the preference of new employees. While the Federal Magistrates Court noted High Court authority that in the absence of direct proof an inference may be drawn from circumstantial evidence if the circumstances give rise to a 'reasonable and definite' inference,(15) the Court was found that it was unable to make such an inference in this case, as the decision not to re-employ the applicant had been made before she lodged her complaint.(16)

These cases illustrate the difficulties complainants have proving racial discrimination in the absence of direct evidence given the apparent reluctance by courts to draw inferences from the existence of systemic discrimination, despite the subtleties and complexities of racial discrimination (and in particular, the way in which decision-makers might be influenced by unconscious racial prejudice).(17) This is particularly acute in cases in the employment context in which the true basis for a decision will often be within the peculiar knowledge of the decision-maker.

3. Racial vilification

Summary of issue

Public acts that are reasonably likely to offend another person and that are done because of the other person's race are unlawful under the racial vilification provisions of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth).

A number of important judicial developments in relation to these provisions are set out below.

In September 2002, the Federal Court of Australia found for the first time that an Australian website that denied the Holocaust and vilified Jewish people was unlawful under these provisions (Jones v Toben).

Serious acts of racial hatred or incitement to racial hatred are not made criminal offences under federal law, although they are made criminal offences in most Australian states and territories. Australia made a declaration upon ratification of the Convention relating to Article 4(a) stating that it will address this issue 'at the first suitable moment'.

Relevance to ICERD

- Article 4

- General Recommendations VII and XV

Where issue is discussed in Australia's 13th and 14th periodic report

Paragraphs 52 - 71

Serious acts of racial hatred or incitement to racial hatred are not made criminal offences under federal law.(18) This is relevant in the context of the obligation contained in article 4(a) of ICERD.(19) Upon ratification of the Convention, Australia declared that:

The Government of Australia... is not at present in a position specifically to treat as offences all the matters covered by article 4(a) of the Convention. Acts of the kind there mentioned are punishable only to the extent provided by the existing criminal law dealing with such matters as the maintenance of public order, public mischief, assault, riot, criminal libel, conspiracy and attempt. It is the intention of the Australian Government, at the first suitable moment, to seek from Parliament legislation specifically implementing the terms of article 4(a).

Serious acts of racial vilification are, however, made criminal offences in most Australian states and territories.(20) There were prosecutions that led to successful convictions in 2004 under the Western Australian Criminal Code 1913. There have been no prosecutions for acts of serious racial vilification under the laws of those other states and territories that make such behaviour a criminal offence within their anti-discrimination laws.

As noted by the Committee in its Concluding Observations on Australia's 10th, 11th and 12th periodic reports,(21) civil provisions were introduced into the RDA by the Racial Hatred Act 1995 (Cth) with the effect that it is unlawful to carry out public acts that are reasonably likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person or group of people because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of the other person or group of people.(22) The RDA exempts from liability anything said or done 'reasonably and in good faith' in relation to:

- An artistic work or performance

- An academic publication, discussion or debate

- A fair and accurate report on a matter of public interest

- A fair comment on a matter of public interest, provided the comment is an expression of the person's genuine belief.(23)

There have been several important judicial developments in relation to the racial hatred provisions since Australia's 10th, 11th and 12th periodic report, which are summarised below.

The jurisprudence in relation to the racial hatred provisions of the RDA establishes that in order to prove that an act was done 'because of' a person's race, colour or national or ethnic origin, a complaint must establish that a causal relationship exists between the reason for the doing of the act and the race of the target person or group.(24) However, a complainant does not need to establish that the respondent intended to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate that person or group.(25) The question for the court is merely whether anything suggests race was a factor underlying the doing of the act.(26)

The courts have held that the test to determine whether an act is 'reasonably likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person or a group of people' is an objective test.(27) It is not necessary to establish that a person was actually offended, insulted, humiliated or intimidated by the impugned act.(28) Rather, the question is whether the act can, in the circumstances, be regarded as reasonably likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate a person with the same racial, ethnic or other relevant attributes of the complainant.(29) However, in order to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate a person, the courts have held that the impugned act must have 'profound and serious effect' on that person, and not just cause 'mere slight or insult'.(30) In determining whether an act is reasonably likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate a person with the complainant's racial or ethnic attributes, the court also considers community standards and the context in which the act was done.(31)

The weight of jurisprudence suggests that that the exemptions to the racial hatred provisions are to be broadly construed on the basis that racial hatred provisions are exceptions to the right to freedom of speech and expression recognised in both international law and the common law of Australia.(32)

In a recent case, Bropho v Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission,(33) the Full Federal Court considered the exemptions under the RDA at some length and in particular, the interpretation to be given to the phrase 'reasonably and in good faith'. The majority of the court held that the test of whether an impugned act was done 'reasonably and in good faith' contains both objective ('reasonableness') and subjective elements ('good faith'). As such, in determining whether an act was done 'reasonably', the courts are required to objectively assess the respondent's actions, having regard to inter alia, whether the act was 'proportionate' to the achievement of a legitimate purpose. In determining whether an act was done in 'good faith', the majority of the Full Court suggested that a respondent will be required to show that they turned their mind to the harm that may be caused by their actions.(34)

Several of the significant court decisions in relation to the racial hatred provisions of the RDA since Australia's 10th, 11th and 12th periodic report include:

-

Bropho v Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission,(35) in which the complainant claimed that a cartoon which appeared in the Western Australian Newspaper breached the RDA. The cartoon concerned the attempts by a group of Aboriginal elders to recover the remains of the Aboriginal leader Yagan who had been killed in 1833, and whose head had been smoked and removed to England for display. The majority of the Court held that the cartoon was an 'artistic work' done 'reasonably and in good faith' and therefore was not unlawful under the RDA.

As set out above, the significance of this case lies in its consideration of the exemptions to the racial hatred provisions and in particular, the interpretation to be given to the phrase 'reasonably and in good faith'.

-

Kelly-Country v Beers,(36) in which the applicant, an Aboriginal man, made a complaint about a comedy performance in which the respondent plays an Aboriginal character, 'King Billy Cokebottle'. In playing that character the respondent applied black stage make-up, an unkempt white beard and moustache, a white or ceremonial ochre stripe across his nose and cheek bones and a battered, wide brimmed hat often associated with Aboriginal Australians who live in rural or outback areas. His routine was delivered in Kriol, or an imitation of it, with an accent common to Aboriginal people in Northern Australia but not all of his jokes directly related to Aboriginal people. The Federal Magistrates Court held that the respondent's performance did not breach the racial hatred provisions of the RDA because a 'reasonable Aboriginal person' would not have been sufficiently offended or insulted by the respondent's performance.

Although not necessary to do so for the outcome of the case, the Court also considered the interpretation and application of the exemption provisions.

- Jones v Toben,(37) in which the Federal Court held that a document published on the internet suggesting that the Holocaust may not have occurred, that it was unlikely Auschwitz contained homicidal gas chambers, that Jewish people who challenged Holocaust denial were of limited intelligence and that some Jewish people exaggerated the number of Jews killed in the Holocaust for improper purposes and financial gain, constituted racial hatred in breach of the RDA. The Court ordered that the document be removed from any website controlled by the respondent and it or similar material not be re-published. This decision of the Federal Court was upheld by the Full Federal Court on appeal.(38) This was the first Australian case involving a challenge to race hate published on the internet.

-

Jones v Scully(39) in which the Federal Court held that the respondent had breached the racial hatred provisions of the RDA by publishing and distributing anti-Semitic literature in letterboxes and selling or offering to sell such literature at a public market. The Court consequently ordered that the respondent refrain from further publishing or distributing the same or similar material, and apologise to the Hobart Hebrew Congregation, on whose behalf the complaint had been brought.

This case was significant because of the Federal Court's finding that the racial hatred provisions of the RDA did not limit the right to freedom of communication protected by the Australian Constitution. In that regard the Federal Court held that they are 'reasonably appropriate and adapted' to the legitimate end of eliminating racial discrimination, a purpose which is compatible with the maintenance of representative and responsible government.

4. Education on human rights and combating prejudice

Summary of issue

HREOC has a number of functions relating to education on human rights that include promoting understanding and compliance with the RDA and awareness of human rights in relation to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In particular, the functions of HREOC contained in section 20(1)(c) of the RDA reflects article 7 of the ICERD.

The educational programs carried out by HREOC provide information and strategies to improve the enjoyment of human rights in Australia, the key message being that the elimination of discrimination and harassment are prerequisites for the enjoyment of human rights by all Australians. A number of programs that may be of interest to the Committee are set out below.

Relevance to ICERD

- Article 7

- General Recommendation V

Where issue is discussed in Australia's 13th and 14th periodic report

Paragraphs 24 - 49

HREOC has a number of functions relating to education on human rights that include promoting understanding and compliance with the RDA. In particular, section 20(1)(c) of the RDA reflects article 7 of the ICERD. It provides HREOC with the following functions:

To develop, conduct and foster research and educational programs and other programs for the purpose of:

- combating racial discrimination and prejudices that lead to racial discrimination;

- promoting understanding, tolerance and friendship among racial and ethnic groups; and

- propagating the purposes and principles of the [ICERD].

Section 46C(1)(b) and (c) of the HREOC Act also provides the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner with roles to promote awareness of human rights and conduct educational programs in relation to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

HREOC has carried out a range of educational programs that include the following:

- National Indigenous Legal Advocacy Courses : A series of nationally accredited training courses which aim to provide Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with the competency and skills to work in a legal environment and to understand their human rights. An important outcome of the program is to improve the legal skills, capacity and training opportunities for Indigenous people, in response to Recommendation 212 of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. The courses are intended to empower Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples by building their capacity to understand and access government services and mechanisms for the protection of their human and legal rights. For further information refer to: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-social-justice/projects/nilac-national-indigenous

- Face the Facts: A factual guide to issues relating to refugees and asylum seekers, migrants and multiculturalism, and Indigenous peoples. The document addresses the most common questions raised in relation to these sectors of Australian society. The written publication is accompanied by an expanded internet version as well as a Face the Facts education resource as part of its Information for Teacher series. The activities link with a range of key learning areas for students in Years 7 - 10 across all states and territories. Teaching notes, student activities and worksheets are provided, plus a range of recommended online resources and further reading. Available online at: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/race-discrimination

- Human Rights Education Resources for the Classroom: A series of documents for teaching human rights, including about race discrimination, in Australian schools that includes links to curriculum documents as well as teaching resources. Available online at: https://humanrights.gov.au/education/teachers. This includes the 'Youth Challenge' series of activities for school students - available online at: https://humanrights.gov.au/education

- Race hate and the internet: The internet has emerged as a significant forum for the dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority and hatred. During 2002, the Commission carried out research into the issue of race hate and the internet. In October 2002, the Commission held a Cyber-racism Symposium attended by senior representatives from the IT sector, government regulators, legislators, academics, racial equality groups and international experts. The summary report of the symposium - covering the difficulties of regulating cyber-racism, Australian and international approaches to the problem and suggested ways of tackling race hate such as education and blocking filters - is available on the Commission's website at: http://www.humanrights.gov.au/racial_discrimination/cyberracism/index.html.

-

Information about HREOC's complaint handling processes: As noted in paragraphs 9 and 10 of Australia's 13th and 14th periodic report, HREOC is responsible for handling complaints under the RDA, as well as the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) ('SDA'), Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) ('DDA'), Age Discrimination Act 2004 (Cth) and the HREOC Act.

HREOC aims to facilitate broad community access to information about its complaint handling processes. In order to achieve this, HREOC provides a range of services that includes the following:

- Information about what amounts to race discrimination or racial hatred (https://humanrights.gov.au/about/contact;

- A concise complaint information brochure sheet for Indigenous people called Discrimination - Know your rights;

- Plain English information guide about the complaints process that can be accessed on HREOC's webpage and downloaded in 14 languages: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/race-discrimination/publications/know-your-rights-racial-discrimination-and-vilification ;

- Interpreter and Translation services. In 2003-04 the main language groups assisted were Farsi/Dari, Vietnamese and Arabic;

- Community education throughout Australia carried out by officers of HREOC. HREOC also employs an Indigenous Liaison Officer in its Complaint Handling Section who has a community education role to inform Indigenous people about their rights and the processes under the laws that HREOC administers.

- Dissemination of information about judicial decisions on racial discrimination: HREOC regularly publishes reviews of federal anti-discrimination law. For example:

- Change and Continuity: Review of the Federal Unlawful Discrimination Jurisdiction, September 2000-September 2002 provided a review of the first two years of the federal unlawful discrimination jurisdiction following the transfer of the hearing function of discrimination matters brought under the RDA, SDA and the DDA from HREOC to the Federal Court and Federal Magistrates Court.(40) Change and Continuity assessed the impact of the changed administration of the jurisdiction on jurisprudence and procedure up to September 2002. It is available online at:

- https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/legal.

- Federal Discrimination Law 2004 examines the jurisprudence that has been developed by courts and tribunals in unlawful discrimination matters brought under the RDA, SDA and DDA. It considers the manner in which interlocutory applications, procedural and evidentiary matters and awards of costs have been dealt with in the Federal Court and Federal Magistrates Court since the transfer of the hearing function from HREOC to those courts on 13 April 2000. It also considers the principles which have been applied to damages awards in cases where breaches of the RDA, SDA and DDA have been found and gives an overview of damages awards made since the transfer of the hearing function. The publication's contents are current to 31 December 2003 and a supplement current to September 2004 is also available.(41) Both documents are available online at: http://www.humanrights.gov.au/legal/fed_discrimination_law_04/index.htm

- Ismaع - Listen: National consultations on eliminating prejudice against Arab and Muslim Australians: The outcomes of the project are discussed in section 3 of this submission.

5. Reform of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission

In recent years, the Federal Government has introduced into Parliament legislation proposing wide-ranging amendments to the HREOC Act which would alter the structure and functions of HREOC. The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed concern about an earlier version of these proposed changes in its early warning decision on Australian in March 1999 and Concluding Observations on Australia in March 2000 (paragraph 11).

The most recent legislative reform, the Australian Human Rights Commission Legislation Bill 2003 lapsed when Parliament was prorogued for an election in August 2004. HREOC expressed a number of significant concerns about that Bill. These are set out in HREOC's submission to the Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee for its inquiry into the Bill. The submission is available at https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/legal/submission-senate-legal-and-constitutional-legislation-committee-1

At the time of writing, the former Bill has not been re-introduced to the federal Parliament. As indicated in the government's periodic report (at paragraph 23), the Government remains committed to pursuing legislative reform to the structure of HREOC.

Where issue is discussed in Australia's 13th and 14th periodic report

Paragraphs 14 to 23.

Section 2: Issues relating to Indigenous peoples (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples)

6. Native Title

Summary

Native title is the name given to the Indigenous customary rights and interests in land and waters that are recognised and protected by Australia's national legal system. The national parliament passed laws in 1993 establishing a system for native title claims to be determined and also to regulate land use where native title may exist. There are three main issues the Committee may wish to consider in relation to native title.

- 1998 amendments - The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination found in 1999 and 2000 that the amended Native Title Act 1993 (NTA) (amended in 1998) is inconsistent with Australia's obligations under the ICERD. The Australian government has responded that it does not agree with the Committee's views.(42) Accordingly, it has not acted in accordance with the Committee's recommendations to amend the legislation and has not entered into negotiations with Indigenous peoples about legislative changes to the Act.

- Consideration of Parliamentary Committee - As noted in the Committee's 2000 Concluding Observations, a committee of the national parliament was considering the concerns expressed by the CERD during 2000. That Committee concluded that it did not agree with the findings of the CERD. The Social Justice Commissioner has expressed concern that this conclusion was reached on the basis of an incorrect interpretation of Australia's obligations under Articles 2 and 5 of ICERD that would permit adverse discrimination of Indigenous people under the NTA.

-

Recent court decisions - Recent decisions of Australia's courts indicate that the Native Title Act extends less protection to native title than is provided by the law to other interests in land. The High Court's decision in Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria & others (December 2002) makes it clear that the standard and burden of proof required to establish the elements of the statutory definition of native title under s223(1)(a) NTA are so high that many Indigenous groups are unable to obtain recognition of the relationship they continue to have with their traditional land. The High Court's decision in Western Australia v Ward & others (August 2002) establishes that native title is permanently extinguished whenever the enjoyment of native title rights and interests is inconsistent with the enjoyment of rights and interests to the land created by the Crown.

Also of concern are decisions of the Federal Court which have interpreted the procedural rights provided in the Native Title Act (Division 3, Part 2, Subdivisions G to N of the Act) to be of limited benefit in protecting native title from impairment by, or involving native title parties in, future developments that take place on land in which native title claims have been lodged or determined.

Relevance to ICERD

The law of native title, both statute law and judicial decisions, provides less protection to traditional native title rights and interests in land and waters than that which is provided by the law to other rights and interests in land potentially breaching Articles 2 and 5 of ICERD. A concern in relation to the above three issues is that because of the unique cultural relationship Indigenous peoples have with their land, the failure to extend proper protection to native title and to allow effective participation results in a restriction on the capacity of Indigenous peoples to enjoy their distinct cultures. This is contrary to paragraph 4 of General Recommendation XXIII which calls on State parties to 'recognise and respect indigenous distinct culture, history, language and way of life as an enrichment of the State's cultural identity and to promote its preservation'.

Where issue is discussed in Australia's 13th and 14th periodic report

Paragraphs 105 - 133.

Section 209 of the NTA requires that the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner prepare and submit annually to the Commonwealth Minister a report on the operation of the NTA and the effect of the Act on the exercise and enjoyment of human rights of Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders. These reports, submitted annually since 1994, examine native title legislation and its consistency with international human rights treaties to which Australia is a signatory, including ICERD.

This is an important role in view of the fact that there is no mechanism to allow a court within Australia to consider whether the NTA is consistent with the legislation that implements Australia's obligations under ICERD, the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (RDA).(43) This follows from the High Court decision in Western Australia v Commonwealth(44) which found that the provisions of the NTA impliedly repeal the protection of the RDA to the extent that there is inconsistency between the two Acts.

The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has previously commented on the amended NTA.(45) In March 1999, the Committee noted that the amendments 'wind back the protections of Indigenous title offered [under previous Australian law...raising] concerns about the State party's compliance with articles 2 and 5 of the Convention'.(46) The Committee also questioned Australia's compliance with article 5(c) of the Convention because of the lack of effective participation of Indigenous communities in amending the NTA.(47) The Committee called on Australia to suspend the amendments and 'reopen discussions with [indigenous Australians]...with a view to finding solutions acceptable to the indigenous peoples and which would comply with Australia's obligations under the Convention'.(48)

Subsequent to the Committee's decisions in 1999 and 2000, the Australian Government has not changed the 1998 amendments or entered into a dialogue with Indigenous Australians about amending the legislation.

A Parliamentary Committee, comprising a majority of government members, examined the 1999 findings of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and sought submissions on whether the amended NTA is consistent with Australia's obligations under the Convention. In June 2000 the Committee issued a report stating that the amended NTA is consistent with Australia's obligations under the Convention and therefore does not need to be amended.(49)

The reasoning of the Parliamentary Committee and its understanding of Australia's international law obligations suggests a standard of equality (referred to as substantive equality) that would permit governments to treat native title holders in a manner that is both differential when compared to the treatment of non-Indigenous title holders as well as adverse in its effect upon native title holders.

The Parliamentary Committee stated that, in applying a standard of substantive equality, differential treatment of a racial group is permissible if:

First, the differences used to justify separate treatment must be genuine and relevant. Artificial and irrelevant differences between groups may not be used as justifications for separate treatment.

Second, where situations are different but analogous, any separate treatment must be appropriately adapted to the extent of the underlying difference. The State must be able to show that the separate treatment is not arbitrary, and can be reasonable and objectively justified by reference to the distinctive characteristics of the groups or individual.(50)

The Aboriginal and Torres strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner is concerned at the way in which the Parliamentary Committee has applied these criteria for substantive equality.

1. Validation provisions

In relation to the validation provisions, it will be recalled that these provisions had the effect of validating acts that detrimentally affected native title holders and would otherwise have been invalid because of the operation of the RDA. It was said by the Parliamentary Committee that validating these acts was a legitimate objective given the reasonableness of the government's assumption at the time. The Parliamentary Committee stated:

The accepted view informed the drafting of the Native Title Act, and was expressed publicly as the position on when and where native title might exist in Australia. Thus, the validation provisions in the 1998 amendments were enacted for the legitimate purpose of providing certainty and to respond to an unforseen legal problem.

On this reasoning the validation of otherwise racially discriminatory acts against native title holders under the amended NTA, is not discriminatory but rather merely differential treatment that serves a legitimate purpose and therefore satisfies the criteria of substantive equality. Similar reasoning was applied by the Parliamentary Committee to the other three provisions of concern to the CERD in 1999 and 2000.

2. Confirmation provisions

In relation to the confirmation provisions, the objective of these provisions was stated as follows: The confirmation provisions were necessary to provide certainty and to ensure the workability of the Native Title Act. Despite the assumption that the grant of a freehold or leasehold interest extinguished native title, the lack of clarity in the Native Title Act, and the court decisions reducing the effectiveness of the threshold test, meant that claims could be made for native title over these tenures. This potentially involved thousands of respondents whose interests were, in fact, not affected by native title. Leaving it to the courts to resolve these issues would be a lengthy and expensive process and could not provide the desired certainty in a reasonable period.(51)

The Parliamentary Committee considered that the objectives of certainty and workability transform what would otherwise be the adverse differential treatment of Indigenous interests in the NTA treatment that mandates the extinguishment of native title, in many cases without compensation, into treatment that meets the criteria for substantive equality. On this basis it was said by the Parliamentary Committee that there is no breach of ICERD.

3. Primary Production Upgrade Provisions

In relation to the primary production upgrade provisions, pastoral leaseholders rights are extended beyond the terms of their lease, to include cultivating land, maintaining, breeding, or agisting animals, taking or catching fish or shellfish, forest operations, horticultural activities, aquacultural activities, leaving land fallow and extracting, obtaining or removing sand, gravel, rocks, soil or other resources. Many of these activities could significantly affect native title interests yet there are minimal procedural rights for native title holders and no capacity for native title holders to negotiate in order to minimise the impact on their rights.

It was decided by the Parliamentary Committee that, applying the criteria of substantive equality, differential treatment that is detrimental only to native title holders can be permitted at international law because it had the following legitimate objective:

In introducing the primary production provisions into the Native Title Act, the Government faced the difficult task of balancing competing interests in land title in Australia. It was required to deal with the unique situation of coexisting rights in a manner that was reasonable and not arbitrary. Balancing the competing rights of native title holders and pastoral lessees was a legitimate objective, given that the original Act had not been drafted to address the possibility of coexistence.(52)

While the Parliamentary Committee said that the objective of these provisions was to balance interests, it is clear that in fact the provisions ensured that pastoral leasehold interests prevailed over native title interests. On the basis of the Parliamentary Committee's reasoning, discriminatory treatment can be seen as 'balancing interests' and thus justifiable as a substantive equality measure.

4. The Right to Negotiate provisions

Similar reasoning is applied in relation to the right to negotiate provisions.(53) In relation to those provisions, the legitimate objective of the amendments was 'to ensure that the right available more closely reflected the nature of the native title rights that were likely to exist on pastoral leases and other tenures where future acts were proposed'(54).

It is of concern to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner that under the reasoning adopted by the Parliamentary Committee and by the government in its submission to the Committee, governments have an extremely wide scope to apply adverse differential treatment to a racial group, while maintaining that their international obligations have been met in the form of substantive equality.

Recent court decisions

There have been four major decisions concerning native title and the NTA by Australia's High Court since the Government's last periodic report.

The Commonwealth v Yarmirr; Yarmirr v Northern Territory (October 2001)(55)

The Court ruled that an exclusive right of Indigenous people to control access to parts of the sea could not be recognised because it was inconsistent with the public right of navigation, the public right to fish and Australia's international obligation to permit innocent passage of ships through Australia's territorial sea. Exclusive rights to traditional sea country, constituted by an elaborate system of laws and customs, were not given recognition. The consequence of this decision is that native title holders receive no benefits from or right to participate in the major natural resource developments taking place in their sea country, including commercial fishing and petroleum exploration.

Western Australia v Ward & o'rs (August 2002)(56)

In this decision (referred to as the Ward decision) the High Court considered two related issues; first the nature of native title, as recognised by the Native Title Act and the common law, and second its susceptibility to extinguishment. In relation to the first issue it found that native title in Australia was a bundle of rights rather than an underlying title to the land. Included in the bundle of rights that make up native title may be such things as a right to hunt and fish, a right to exclusive use of the land, a right to control access and a right to make decisions in relation to the land. The Court found that there was no underlying title to the land outside of the particular rights that could be exercised in relation to the land. This concept of native title has consequences for the second issue dealt with by the court, the extinguishment of native title.

The extinguishment of native title arises from two sources. First it arises from the NTA which prescribes the extinguishment of native title in two sets of provisions, the validation provisions and the confirmation provisions.(57) Where native title is not extinguished by the operation of the NTA it may still be extinguished by the operation of the common law. The test for determining whether native title is extinguished by this second source was outlined in the Ward decision. The High Court emphasised that the common law is shaped by its statutory context in the NTA. Within this context it found that native title may be extinguished, either partially or completely, by laws or acts which create or have in the past created rights in third parties. Where there is an inconsistency between the rights created by the Crown for the benefit of third parties and the native title rights arising out of traditional law and custom, native title will be extinguished, either completely or partially, to the extent of the inconsistency. This test is known as the inconsistency of incidents test. It applies not only to determine whether current tenures extinguish native title but also to determine this question in relation to every tenure that has been created throughout the history of settlement over the land the subject of the native title claim.

In the Ward decision the application of this test resulted in the extensive extinguishment of native title either completely or partially. For instance the creation of a nature reserve under Western Australia's Land Act 1933 extinguished native title completely. Where native title was only partially extinguished, native title rights that best survived the inconsistency of incidents test were those which were expressed at a high level of specificity;(58) were limited to the conduct of activities on the land rather than the control of activities on the land;(59) and confined those activities to traditional activities rather than contemporary activities. Thus, for example, a right to dig for ochre may survive the grant of a mineral lease on the same land while a right to utilise the resources of the land would be extinguished. Similarly a right to hunt and gather may survive the grant of a pastoral lease while a right to control access to the land or make decisions about the use of the land would not.

The inconsistency of incidents test operates at common law to determine whether tenures created throughout the history of settlement in Australia extinguish native title. It is only applied after the court has considered whether the NTA has already prescribed the effect of the creation of the particular tenure upon native title. If native title survives the application of the NTA then the question arises whether native title is extinguished in any event by the common law.

It is clear that the government has the power to enact legislation that would protect native title from extinguishment sourced in the common law. Yet no legislative action has been taken to do this. In addition, the NTA fails, in the majority of cases, to provide compensation for the extinguishment of native title.

Wilson v Anderson & o'rs (August 2002)(60)

In August 2002 the High Court found that perpetual grazing leases could be classified as 'freehold estate' under s23B(2)(c)(ii) of the NTA and that they wholly extinguished native title.(61) The Wilson v Anderson decision applies to perpetual grazing leases throughout the Western Division of the State of New South Wales. The Western Division covers approximately 43 per cent of New South Wales and of this area over 96 per cent is held under perpetual grazing leases.(62) The decision has had significant implications for traditional owners in the area.

Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria & others (December 2002)(63)

The High Court's decision in Yorta Yorta makes it clear that the standard of proof required to establish the elements of the statutory definition of native title under s223(1)(a) NTA is high such that many Indigenous groups are unable to obtain recognition of the relationship they continue to have with their traditional land.

Section 223(1)(a) of the NTA requires that the rights and interests that can be recognised as native title must be possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the peoples concerned. This has been interpreted by the Court in the Yorta Yorta decision to require proof of continuous observance and acknowledgement of those laws and customs since the British acquisition of sovereignty over Australia.

The Court found that the effect of the British Crown acquiring sovereignty over Australia is that the Indigenous systems of traditional laws and customs that created rights and interests prior to sovereignty could not validly continue to do so upon sovereignty being acquired. From this point Indigenous laws and customs were replaced by the legal system of the new sovereign. Thus recognition of native title rights and interests is restricted either to those created by Western law or to those created by Indigenous laws and customs before the acquisition of sovereignty.(64) The Court held that the native title rights to which the NTA refers are rights and interests created before sovereignty by Indigenous laws and customs. This is what is to be understood as 'traditional' in the phrase 'traditional laws and customs' in s223(1)(a).

The Court also held that the claimants must establish that there has been continuous observance and acknowledgement of the laws and customs of Indigenous people since sovereignty. In order to show this they must also show that, since sovereignty, the society observing these Indigenous laws and customs has not ceased to exist(65).

It was recognised by the High Court that real evidentiary difficulties arise from the tests applied to Indigenous applicants seeking recognition of native title. The questions that arise and which they must satisfy include: What is the content of pre-sovereign laws and customs?(66) Are the rights and interests presently possessed, rights and interests possessed under pre-sovereign laws and customs?(67) Are differences between the rights and interests presently possessed and those possessed before sovereignty differences which result from developments of or alterations to the traditional laws and customs or are they differences that result from new laws and customs that are generated after sovereignty?(68) When does an interruption to the observance of traditional laws and customs amount to cessation of their observance?(69) When can it be said that the observance of laws and customs is by a new society even though the laws and customs are similar to or even identical with those of pre-sovereign society?(70)

Providing a satisfactory answer to these questions is made even more difficult for applicants by the fact that the traditional laws and customs are transmitted orally from generation to generation. In the cultural context in which proof of these very difficult elements are required, the amendments to s82 of the NTA can be seen as a further denial of the rights of Indigenous people to cultural equality. Under this provision in the original NTA a Court was 'not bound by technicalities, legal forms or rules of evidence'(71) and was bound to 'pursue the objective of providing a mechanism of determination that is fair, just, economical, and prompt'.(72) Under the amendments a new s82 provides that the Court is bound by the rules of evidence 'except to the extent that the Court otherwise orders'.(73) The difficulty of building a base for the court to draw inferences on the content of traditional laws and customs prior to sovereignty, their ongoing transmission from generation to generation by oral form and their present possession is, under these amendments, almost insurmountable.

Further Court Decisions

Also of concern to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner are two decisions of the Federal Court which have interpreted the procedural rights provided in the NTA (Division 3 Part 2 of the Act) to be of limited benefit in protecting native title from impairment by, or involving native title parties in, future developments that take place on native title land by government.

In Lardil, Kaiadilt, Yangkaal and Gangalidda Peoples v Queensland (April 2001)(74) the Court held that the failure of the State to comply with the procedural requirement in the NTA to notify and give native title parties in pending litigation or native title holders an opportunity to comment on proposed activity on a native title area did not affect the validity of the activity. These procedural rights are important to ensure Indigenous participation in developments that occur on traditional land.

In Harris v Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (May 2000)(75) the Full Federal Court found that, in relation to the notification provisions within section 24HA of the Act there was no requirement to notify the registered native title claimants before an Authority had determined to grant the permit requested.(76) These decisions by the Federal Court indicate the limited extent to which procedural rights under the NTA can protect Indigenous interests from the impact of development.

Conclusion

The developments in native title law and practice have not removed or alleviated the matters that concerned the Committee in its previous assessment of native title. Indeed, recent court decisions indicate that native title is a weak title in land subservient to all other interests.

The Social Justice Commissioner recognises however that new administrative structures for implementing government policy in relation to Indigenous peoples, introduced by the government in July 2004(77), provides an opportunity for government to develop a positive relationship with Indigenous peoples so as to ensure that native title promotes their human rights. Some of the government's functions in relation to native title are being administered through this new structure.

A further opportunity is provided through the native title agreement making process. The amendments to the NTA introduced extensive provisions for the making of Indigenous Land Use Agreements. These amendments provide the mechanisms by which a variety of agreements can be reached and registered under the Act. These provisions offer significant potential for governments and traditional owner groups to tailor native title agreements to the economic, social and cultural development needs of Indigenous peoples.

7. Indigenous disadvantage

Summary of issue

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples do not enjoy an equal standard of living to all other Australians. Since 2000, there have been some significant developments in addressing Indigenous disadvantage, most notably commitments by all Australian governments to work together through the Council of Australian Governments (COAG). This has involved the introduction of a national reporting framework for overcoming Indigenous disadvantage, commitments to introducing benchmarks and targets to address this and eight coordinated community trials (the COAG trials). The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner has commended these efforts, while also expressing concern at:

- the lack of adequate progress in improving the socio-economic situation of Indigenous peoples;

- the lack of progress in developing action plans and benchmarks since the time that commitments to these processes were made in 2000; and

- non-compliance with Australia's treaty obligations to progressively realise improvements in indigenous disadvantage.

Relevance to CERD

- Articles 1(4), 2(2) and 5

- General Recommendation XXI and General Recommendation XXIII

Where issue is discussed in Australia's 13th and 14th periodic report

Paragraphs 80-82

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples do not enjoy an equal standard of living to all other Australians. This has been a matter of great concern to governments, the Australian community and international bodies for some time (see for example, paragraph 18 of the 2000 Concluding Observations by the Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination).

Commitments by the Council of Australian Governments

Since 2000, there have been some significant developments in addressing Indigenous disadvantage, most notably commitments of the COAG.

In its communiqué of 3 November 2000, the COAG committed to overcoming Indigenous disadvantage by focusing on three priority areas: community leadership; reviewing and re-engineering programs and services to support families, children and young people; and forging links between the business sector and Indigenous communities to promote economic independence. As part of this process, it was agreed that Ministerial Councils (which are constituted of the minister from each jurisdiction at the federal, state and territory level in a portfolio area) were to develop 'action plans, performance reporting strategies and benchmarks' with COAG to review progress regularly.

In its communiqué of 5 April 2002, COAG agreed to conduct a number of whole-of-government community trials across Australia. It also decided to commission a reporting framework on key indicators of Indigenous disadvantage. The Productivity Commission, as Chair of the Steering Committee for Government Service Provision, was requested to develop this monitoring framework for Indigenous disadvantage.

In its communiqué of 24 June 2004, COAG committed to cooperative approaches on policy and service delivery between agencies and to maintaining and strengthening government effort to address indigenous disadvantage. COAG agreed to a National Framework of Principles for Government Service Delivery to Indigenous Australians to achieve this. This Framework is due to be implemented with bilateral arrangements between the Commonwealth and state and territory governments. At the time of writing, these had not come into existence.

Monitoring framework for overcoming Indigenous disadvantage

The most substantial development since Australia's previous appearance before the Committee is the agreement by all Australian governments to a monitoring framework for Indigenous disadvantage.

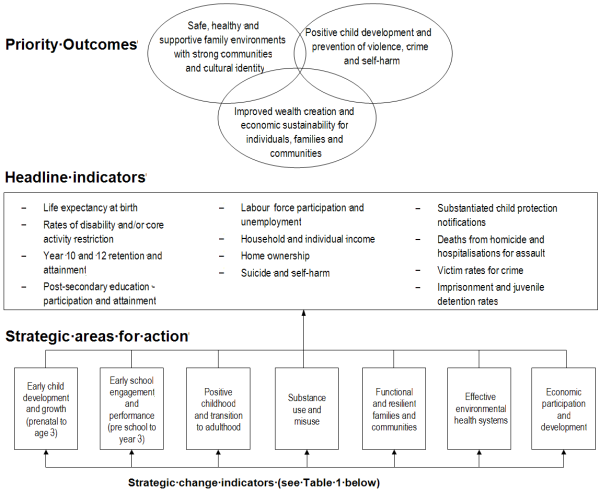

This framework, developed by the Productivity Commission (as Chair of the Steering Committee for Government Service Provision), establishes a three tiered framework to measure the actual outcomes for Indigenous people as opposed to the operation of specific policy programs. The framework is contained in the diagram on the next page.

The first, or overarching, tier relates to outlining the three priority outcomes of:

- Safe, healthy and supportive family environments with strong communities and cultural identity;

- Positive child development and prevention of violence, crime and self-harm; and

- Improved wealth creation and economic sustainability for individuals, families and communities.(78)

Diagram - COAG Framework for reporting on Indigenous disadvantage

![]() Diagram - COAG Framework for reporting on Indigenous disadvantage (PDF)

Diagram - COAG Framework for reporting on Indigenous disadvantage (PDF)

The framework seeks to report on Indigenous disadvantage on a holistic and whole-of-government basis. As such it is:

predicated on the view that achieving improvements in the wellbeing of Indigenous Australians in a particular area will generally require the involvement of more than one government agency, and that improvements will need preventative policy actions on a whole-of-government basis...(79)

The framework acknowledges that areas such as health, education, employment, housing, crime and so on are inextricably linked. Disadvantage or involvement in any of these areas can have serious impacts on other areas of well-being. It is also premised on a realisation that there are a range of causative factors for Indigenous disadvantage. This necessitates reporting on progress in addressing both the larger, cumulative indicators (such as life expectancy, unemployment and contact with criminal justice processes) which reflect the consequences of a number of contributing factors, as well as identifying progress in improving these smaller, more individualised factors.

To reflect these strategic considerations, the framework seeks to present progress in addressing Indigenous disadvantage at two levels (the second and third tier of the framework). The first level, which is the second tier of the framework, is a series of twelve 'headline indicators' that provide a snapshot of the overall state of Indigenous disadvantage.

These 'headline indicators' are measures of the major social and economic factors that need to be improved if COAG's vision of an improved standard of living for Indigenous peoples is to become reality. As it is difficult to measure progress in change in these indicators in the short term, the framework also has a third tier of indicators. There are seven 'strategic areas for action' and a number of supporting 'strategic change indicators' to measure progress in these. The particular areas and change indicators have been chosen for their 'potential to respond to policy action within the shorter term... (and to indicate) intermediate measures of progress'(80) while also having the potential in the longer term to contribute to improvements in overall Indigenous disadvantage (as reflected through the 'headline indicators')(81). The seven strategic areas and related indicators are set out in the following table.

Table: COAG Overcoming Disadvantage framework: Strategic areas for action and strategic change indicators(82)

| Strategic areas for action | Strategic change indicators |

|---|---|

| 1. Early child development and growth (prenatal to age 3) |

|

| 2. Early school engagement and performance (preschool to year 3) |

|

| 3. Positive childhood and transition to adulthood |

|

| 4. Substance use and misuse |

|

| 5. Functional and resilient families and communities |

|

| 6. Effective environmental health systems |

|

| 7. Economic participation and development |

|

The Steering Committee published its first report against this framework, titled Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage - Key Indicators 2003, in November 2003. The report confirms that Indigenous disadvantage is broadly based, with major disparities between Indigenous and other Australian in most areas.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner has commented that the 'endorsement of the framework by COAG in August 2003 and the production of the first report by the Steering Committee in November 2003 are both substantial achievements' towards achieving reductions in Indigenous disadvantage.(83)

Benchmarks and targets to measure progress towards reducing Indigenous disadvantage

The introduction of this framework is important in focusing on the progress in addressing Indigenous disadvantage. As noted above, this process was agreed alongside a second process to develop action plans through Ministerial Councils for addressing Indigenous disadvantage. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner noted in 2003:

the long-standing commitment of governments to develop benchmarks and action plans for key areas of Indigenous disadvantage through the various inter-governmental ministerial councils remains largely unfulfilled. Accordingly, it is not possible to determine whether government efforts to address Indigenous disadvantage have progressed at a rate that meets the expectations (and targets) of governments and Indigenous peoples. There are no publicly reported goals setting out what is an acceptable rate of improvement against which we can determine whether current progress is adequate and fully matches the potential of available resources and programs.(84)

The Social Justice Report 2003 reviewed the status of these action plans and found that:

- the 'Action plans and strategies adopted at the inter-governmental level to date do not contain critical elements for benchmarking' such as 'an agreed rate of progress towards (the goal of equality), within a short, medium and long term context, and

- an evaluation of issues relating to the prioritisation, resourcing and re-engineering of programs and services that will be needed in order to achieve this'(85).

It concluded that 'The absence of appropriate benchmarks is perhaps the most significant failure of governments in implementing... reconciliation since the year 2000'(86).

Progress in addressing Indigenous disadvantage

As noted above, progress to address Indigenous disadvantage has been slow in recent years. Information about this is set out in the table below. Nevertheless, it is acknowledged that the Government has commenced major reforms to service and program delivery to Indigenous peoples in July 2004 as part of its commitment to overcoming Indigenous disadvantage. These are discussed in item 11 below. It will be some time before any tangible and measurable outcomes can be reported from these new initiatives.

Table: Progress in addressing Indigenous disadvantage

Income

- Gross household income for Indigenous people increased by 11% between 1996 and 2001. In 2001, it was 62% of the rate for non-Indigenous Australians, compared to 64% in 1996.

- Median gross individual income for Indigenous people increased by 19% from 1996 to 2001, compared to an increase of 28.4% for non-Indigenous people. There has been a considerable increase in the disparity in individual income between these two groups between 1996 and 2001, as well as over the decade from 1991 to 2001.

Employment

- In 2001, 54% of Indigenous people of working age were participating in the labour force compared to 73% of non-Indigenous people.

- In 2001, the unemployment rate for Indigenous people was 20% - an improvement from the rate of 23% in 1996. This is three times higher than the rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

- 18% of all Indigenous people in employment in 2001 worked on a CDEP scheme. If CDEP were classified as a form of unemployment, the Indigenous unemployment rate would rise to over 34%.

Education

- 69% of Indigenous students progressed from year 10 (compulsory) to year 11 (non-compulsory) schooling, compared to 90% of non-Indigenous students in 2001.

- 38% of Indigenous students were retained to year 12 in 2002 compared to over 76% for non-Indigenous students. This was an increase from 29% in 1996.

- In 2001, Indigenous people participated in post-secondary education at a similar rate to non-Indigenous people, although they had a slightly higher enrolment rate at TAFE colleges and a lower enrolment rate at universities. The proportion of Indigenous youth (aged 15-24 years) attending a tertiary institution declined between 1996 and 2001.

Housing

- In 2001, 63% of Indigenous households were renting (compared to 27% of non-Indigenous households), and 13% owned their home outright (compared to 40%).

- Indigenous people are 5.6 times more likely to live in over-crowded houses than non-Indigenous people.

Contact with the criminal justice system

- Indigenous people have consistently constituted 20% of the total prisoner population since the late 1990s, compared to 14% in 1991.

- Indigenous people are imprisoned at 16 times the rate of non-Indigenous people. Indigenous women are imprisoned at over 19 times the rate of non-Indigenous women. These rates are higher than in 1991, when the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody reported.

- Since 1997, Indigenous juveniles have constituted at least 42% of all incarcerated juveniles, despite constituting 4% of the total juvenile population. In 2002, Indigenous juveniles were incarcerated at a rate 19 times that of non-Indigenous juveniles, an increase from 13 times in 1993.

Contact with care and protection system

- Indigenous children come into contact with the care and protection system at a greater rate than non-Indigenous children, and are increasingly represented at the more serious stages of intervention.

Of particular concern is the lack of achievement in relation to improving the health status of Indigenous Australians. The table below illustrates this.

Table: Indigenous Health status

Life Expectancy and median death age

- In 2001, the national median death age of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (male and female combined) was 54 years, approximately 24 years less than that in the general population. Data collections show that while the median death age for the general population has increased steadily over the past decade, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander age has fluctuated(87). In 2003, there was no national median death age figure published. Rather, it was calculated on a State/Territory basis. It ranged from between 46 and 56 years for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males and between 50 and 62 years for females(88).

- Because large numbers (approximately 45%) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are apparently not identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander on death certificates, their life expectation is estimated. The formulae used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics from 1997 - 2001 suggested that life expectation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females decreased slightly from 63 to 62.8 years over that period. For males, it increased from 55.6 to 56.3 years. It also showed that the life expectation inequality gap worsened: between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and general population males, the gap increased from 20.6 to 20.7 years; and between females, it rose from 18.8 to 19.6 years(89).

- In 2003 the Australian Bureau of Statistics began using a new Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander life expectation formula based on five year periods. Under this, it is not possible to ascertain if life expectation increased or decreased over 1997 - 2001. Under the new formula a life expectation inequality gap of about 18-years is identified, a reduction of about three years on the 1997 - 2001 formula. The new formulae is believed to more accurately reflect what Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander life expectation is. The next figure will be calculated over 2001 - 2006(90).

Infant health

- Approximately twice as many low birth weight babies were born to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women compared to those born to non-Indigenous women over 1998 - 2000.(91) The ABS and the Australian Institute of Health Welfare (AIHW) reported in 2003 that since 1991 there appears to be no change in both the rates of low birth-weight babies being born to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and the mean birth weights of those infants(92).

- Approximately twice as many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants die before their first birthday as non-Indigenous infants(93).

- Rates of infant mortality for Indigenous people in Australia are significantly higher than rates for Indigenous people in Canada, the USA and New Zealand.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner has also expressed concern about the impact of the demographic characteristics of the Indigenous population on future efforts to reduce Indigenous disadvantage. As stated in the Social Justice Report 2003:

Not only is the Indigenous population growing at a faster rate than the non-Indigenous population (2.3 per cent compared to 1.2 per cent annually), but the Indigenous population's median age is younger (20 years compared to 35 years) and nearly twice as many Indigenous compared to non-Indigenous people are under 15 years of age (almost 40 per cent compared to just over 20 per cent). Similarly, only 2.8% of the Indigenous population are aged over 65 compared to 12.5% of the non-Indigenous population. The consequence of this age structure and rate of population growth is that there will be a significant increase in the number of Indigenous people entering the age group where they will be seeking employment.(94)

This makes the challenge of reducing Indigenous disadvantage even more daunting in the coming years, and highlights the need for better benchmarks and targets for addressing this situation.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner stated in the Social Justice Report 2003:

Overall, the statistics across key areas of Indigenous disadvantage for the past five years indicate that there is no consistent forward trend in reducing the extent of disadvantage experienced by Indigenous peoples, and limited progress in eradicating the disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. There is some evidence that in relation to key measures, this situation may deteriorate further in the coming decade. The outcomes being achieved by governments are not adequate on any measure of success and despite the investment of significant resources by governments. This situation needs to change.(95)

The level of Indigenous disadvantage raises concerns in relation to Australia's obligations under Articles 1, 2, and 5 of the ICERD.

The disproportionate rate of disadvantage faced by Indigenous people indicates that they do not enjoy the full spectrum of human rights in a non-discriminatory manner. The achievement of the non-discriminatory enjoyment of the full spectrum of human rights for all people is one of the core obligations undertaken by States parties to the ICERD.

The consequence of this disadvantage is that Australia is required under Articles 1(4) and 2(2) of ICERD to take special measures to ensure the adequate development and protection of Indigenous people, for the purpose of guaranteeing them the full and equal enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms, and to do so within the shortest possible timeframe.

8. Mandatory detention laws in the Northern Territory and Western Australia

Summary of issue

In August 2001, the Northern Territory government repealed mandatory sentencing provisions for juvenile and adult property offenders. This addresses the concern raised by the Committee in its March 2000 Concluding Observations on Australia.

The Western Australian laws, however, continue to operate. This is despite a government review of them finding the possibility of the law producing 'unfairly harsh and counterproductive outcomes'.

Relevance to ICERD

- Articles 2 and 5.

Where the issue is discussed in Australia's 13th and 14th periodic report

Paragraphs 154 - 160

Northern Territory

The NT government repealed mandatory sentencing laws for juvenile and adult property offenders on 18 October 2001. This addresses the concern raised by the Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in its March 2000 Concluding Observations on Australia.

Western Australia