Getting serious - Our experiences in elevating the representation of women in leadership - A letter from business leaders (2011)

Our

experiences in elevating the representation of women in leadership

A letter from business leaders

Getting serious

In our

companies we see progress from building an understanding of gender diversity and

taking the actions described in Phase 1. However, for most of us, these alone do

not meet our aspirations. The next transition occurs when we move from an

interest in elevating women in leadership, to an understanding that we must

actively drive change in the same way that we do for any transformational

business imperative.

A company

cannot transition to Phase 2 until the CEO has conviction. This increase in

commitment makes sense for a variety of reasons. For some of us, there are

business grounds for making the next move. Some of us think of it as a moral

imperative—we want our daughters to have the same opportunities as our

sons.

However,

for most it is a fundamental belief that our organisations will be disadvantaged

if we do not leverage half of our population. Many of us also believe that a

company culture that does not support the advancement of women will be

increasingly unattractive to the next generation of talent.

Companies

who are further along in the journey have a more penetrating approach to

managing the objective. Leadership becomes more driven—there is a

transition from asking questions and supporting programs to managing gender

balance as a business imperative—alongside other priorities such as

customer service, new markets or productivity improvement.

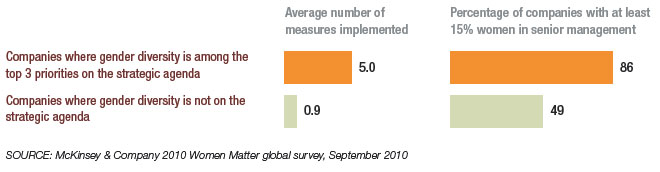

As Exhibit

9 shows, McKinsey’s Women Matter global research finds that having gender

diversity as a top strategic priority correlates directly to the actions a

company takes on gender diversity, and to the number of women in senior

management. This makes sense, but what actions need to be taken?

Essentially,

we must eliminate obstacles to merit-based appointments of women. For some,

tweaks or targeted interventions are required, so that talent processes can be

harnessed to drive change.

In the

first phase, HR led the charge with our support. In this second phase the

leadership team takes over. The task in the second phase is to provide strong

leadership, and where required, intervene to manage the talent pipeline to

deliver the best outcomes. People processes must deliver and develop the best

people—regardless of gender.

By

integrating the goal of elevating women’s representation in leadership

into the business agenda, companies move further towards achieving gender

balance than by relying on CEO personal interest and programs alone.

Exhibit 9: Having gender diversity on the top of the

strategic agenda is critical

By

ensuring targets are in place, well understood and hardwired into scorecards,

senior leaders become good at identifying barriers—and intervening to

offset their impact. All of this adds up to improved results against objectives.

Exhibit 10 describes how ANZ embeds its gender balance aspiration into its

overall strategy.

However,

there are risks, namely that the focus on women can be seen as compromising

rather than enhancing our

talent. ‘It’s important to be clear that my active interest and targets

don’t guarantee a woman a job or promotion. What they do is to increase

the probability that a talented woman will be considered alongside a talented

man’, says

Andrew Stevens from IBM.

In this

phase, the five most impactful actions are:

1.

Make the leadership team the diversity council. With an up shift in

commitment, we personally set and monitor progress against our diversity

strategy.

Ralph

Norris transitioned CBA’s diversity council from people with experience in

diversity, to the full executive committee—to better align accountability.

In the past, CBA’s diversity council might have provided advice, but no

specific action plan. Now, the diversity council ‘owns’ elevating

women’s representation in leadership. Meetings that used to be about

education are now about decisions and corrective action.

Says Gail

Kelly of The Westpac

Group, ‘the diversity council is chaired by me and made up of the full executive

committee. It needs to be us—we can call each other out and we can hold

each other to account. As the council evolves it may expand, but for now we own

it.’

Telstra’s

diversity council, established in 2006, is chaired by David Thodey and comprises

six of his direct reports. This group provides strong strategic oversight and

draws connections across the organisation so that diversity and inclusion is

business-focused, aligned and deeply connected to customer, community and people

outcomes. Council members monitor key metrics and engage local groups to further

embed change.

2.

Signal change with the appointment of women to key roles. A number of us

describe needing to ‘prime the pump’ by making or facilitating key

appointments—whilst ensuring the appointments are solid. We all agree this

must be done without compromising meritocracy. We do this by becoming more aware

of the women around us. We also seek out those we may not have immediate

exposure to. Some of us deliberately remove barriers where meritocracy might be

failing. Others admit to simple good luck and fortuitous timing.

These

appointments signal a new diversity paradigm. At Woolworths, Michael

Luscombe’s appointment of two women into line roles in the senior

executive team signalled that promotion would not just be given to those with

years of technical experience, but that leadership qualities were also critical

to selection.

When

Stephen Roberts from Citi was looking for someone to join his team, he reached

out to a woman he knew who had started her own business. ‘I

asked her to tell me all the reasons it wouldn’t work. Then, I told her

what I was prepared to do to make it

work.’ Eighteen

months later, she has been nominated for a significant award by her

peers. ‘I often think of the others who are not getting that phone call. What a

waste’, says

Stephen.

Alan Joyce

of Qantas states,

‘it’s

often about getting people to consider candidates who aren’t on the radar.

That drives the different outcomes.’

3.

Shift from ‘diversity maths’ to measuring and managing

KPIs. At this point,

we understand our ‘diversity maths’ well. From that foundation, we

move from a general to a granular view of the opportunities. We set realistic

and specific targets for each part of our organisation. We communicate the path

to achieving them. Plans are created and measured against. Diversity metrics

move from being separate scorecards to being embedded in reviews. Traditional

reasoning that diversity results are outside our control becomes unacceptable.

For

example, at Citi, a simple, achievable target focused on the CEO’s direct

reports worked well. Says Stephen Roberts, ‘We

needed a goal that would make a real difference, that was easy to measure, that

would build confidence. We also needed to ensure that we provided support for

groups who didn’t have a natural pipeline of women ready to take on

leadership roles. When provided the support, the knowledge and resources, it was

amazing how much progress we made in only a few

months.’ This experience is described in Exhibit 11.

Our

companies take different approaches to communicating targets. The Westpac Group

employed a mix of both internal and external communications to reinforce its

commitment. ‘Our

partnership with UN Women’s International Women’s Day served to

drive momentum internally, to raise the profile of key women in the pipeline,

but also to send a very public signal about the level of commitment and our

confidence about reaching our

goal’, says

Gail Kelly.

Some of us

fear over-communicating targets or results because it might imply a move away

from merit-based appointment—and raise suspicions that women did not

‘earn’ their promotions.

In this

phase, companies also move towards considering the quality of the women in the

pipeline, not just the quantity. For example, at Woolworths, all talent

discussions include consideration of the proportion of female talent in the high

potential and promotable pools, as well as in the top 1000.

4.

Intervene on talent. We are aware of

patterns of hiring and promotions that don’t support our goal of

developing the best talent regardless of gender. Many of us report intervening

to get the right merit-based outcomes.

We become

increasingly aware that our processes overlook talented women, and therefore do

not support true meritocracy. We seek out ways to fix this tilted playing field:

(i)

Zero-in on top talent pools and high performer

programs. Many of us

emphasise getting to know the women in our senior talent pools, leading to

several key appointments. Many of us are still in the early stages of tracking

promotion slates and succession planning to ensure that deserving women are

considered.

Some of us

have set goals for women representation in talent pools above the current share

of roles, to ensure sufficient access to opportunity.

IBM’s

leadership program integrates the company’s pipeline management and

succession planning process. IBM focuses on promoting women via managing a

‘women ready for promotion’ list. This is consulted when leadership

programs become available or new executive roles arise. All executive benches

must have at least one female candidate.

Mike Smith

and his team at ANZ talk about ‘early

and activist career and succession planning to ensure we are creating a strong

pipeline for line and business

roles’. Women

are encouraged to think through their aspirations and the critical experiences

they need to achieve their goals. A clear career plan is important for employees

with leadership aspirations, particularly those who may take time

out.

(ii)

Bet more on leadership intrinsics in

appointments. Many of

us regularly question overly narrow experience requirements that might leave

women out. We observe that women’s experience might feel more

‘choppy’ than their male counterparts—due to factors such as

parental leave or a limited ability to consider mobility options.

In the

Australian Public Service, leaders work to interpret career break experiences,

such as leadership of a school’s Parents and Friends Committee, or a pro

bono role with the not-for-profit sector, into their evaluation of candidates.

(iii)

Transition to sponsorship, not

mentorship. Many of

us decide that our traditional approaches to mentorship are not enough. We

believe we need to provide not just general guidance for women, but also support

that helps them get promoted.

Exhibit 10: Embedding the diversity aspiration at

ANZ

| |

Previous

approach |

Current

priorities and actions |

|---|---|---|

|

Governance/strategy

|

|

|

|

Recruiting

|

|

|

|

Learning

|

|

|

|

Pipeline

|

|

|

|

Retention

|

|

|

Exhibit 11: Target setting: learnings from Citi

| |

From

July 2010 |

To

July 2011 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Goal

characteristics |

|

|

|

|

Words

used |

|

|

|

|

Communications

|

|

|

|

|

Accountability

and support |

|

|

|

|

Impact: 9% increase in women in top 2 levels (from CEO)

|

Lessons

learned: General goal does not work, better to have:

|

||

Exhibit 12: Sponsorship at Goldman Sachs

|

Context

and Objectives Leaders

were disappointed with the promotion rates of senior women, which lagged rates of their male counterparts. Many women were seen as having a lower profile than their male counterparts. They also had fewer advocates on average from outside the business. Goldman

Sachs in Australia is working to close this gap, through a formal sponsorship program for senior women. The firm has already experienced a successful rollout of the program in Asia. |

|

|

Actions

Taken

|

Lessons

Learned

|

Exhibit 13: NAB Diversity and Inclusion Service Provider

Principles

|

Summary

of expectations for search and recruiting firms |

|

|

Supporting

NAB’s aspirations Service

providers will:

|

Metrics

to track success Service

providers must also provide progress updates, including KPIs to NAB on a quarterly basis that cover:

In

addition, shortlists for senior management roles must include at least one woman of sufficient quality/suitability recommended for interview. If such a candidate is not presented, a written explanation is required each time |

For

example, McKinsey & Company interviews with over 100 remarkable women

leaders globally found that for many female leaders there was a key individual

who believed in them. This sponsor shaped their professional destiny by pushing

them hard, opening the right doors, and giving them honest feedback when they

were veering off track. These efforts went well beyond ordinary mentoring

relationships—sponsors stuck their necks out, they looked for and created

opportunities for these women because they wanted their protégées

to succeed.

Many of us

also believe that sponsorship is particularly important in the first 3-5 years

of a woman’s career, not just when they are close to achieving a senior

role. Sponsorship during these early years where expectations are being

set—both the organisation’s and the woman’s—can make a

difference in their early trajectory, and in the likelihood that they will

strive for senior roles later on.

At ANZ,

this means building the expectation that sponsorship is a key role of senior

leaders and emphasising its importance for women. All executive teams are

expected to know the women in their divisions who are part of talent and

graduates programs. Leaders are encouraged to engage and sponsor women through

meaningful work experiences, by identifying and building career paths, and

through regular people planning processes.

As Exhibit

12 shows, Goldman Sachs is rolling out a program that holds senior executives

responsible for the success of specific women. ‘Sponsorship

is about moving from coffee chats and advice, to actually backing our women, and

feeling responsible for their career success. It’s a real mindset

shift’, says

Stephen Fitzgerald.

Andrew

Stevens of IBM spoke at and attended various activities over three days of the

company’s women’s leadership training earlier this year, ‘It

was deeply satisfying. Fifteen of the eighteen senior women attending have had

real breakthroughs since then. Many have said my attendance helped. It also

allowed me to get in touch with, and to some extent, remove, barriers. It also

sent a message about just how important elevating women’s leadership is to

me.’

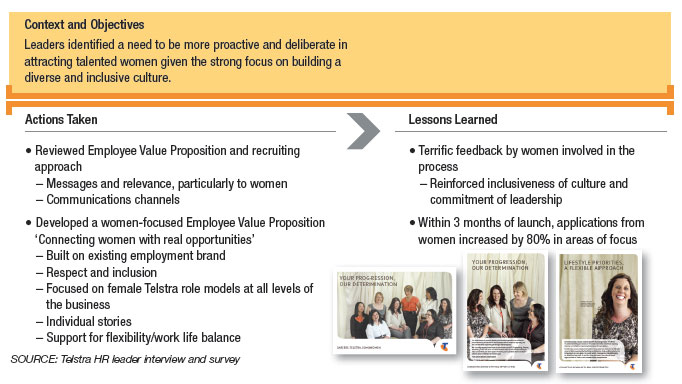

Exhibit 14: Telstra’s female employment brand

(iv)

Ensure your attraction engine is

delivering. Some of

our companies are working to increase the number of women brought in through

external appointments, especially into areas that are particularly male

dominated. As we focus on women talent, our search partners need to as well.

Most of us are now insisting on women candidates for all senior external

searches, where in the past, it was common for none to be presented at all.

For

example, NAB has introduced Diversity and Inclusion Service Provider Principles

that apply from 2012. These principles, outlined in Exhibit 13, require

recruitment partners to provide information regarding their diversity strategy.

Areas to be covered include strategic actions, training and processes that will

achieve the supplier’s stated diversity strategy. Reporting on the gender

ratio along each step of the recruiting process must also be submitted,

including the initial pool of candidates, screening, selection, and

short-listing for all roles. There is also a requirement that at least one woman

of sufficient quality will be recommended for interview.

Many of us

are re-thinking our own recruiting strategy, in the hopes of attracting more

women at all levels. Exhibit 14 describes Telstra’s recent efforts to

improve its recruiting approach, which resulted in the creation of a segmented

employment brand for women. This approach has more than doubled applications

within targeted areas, in the first three months of its

implementation.

Citi is

taking an innovative approach to leveraging its networks to attract women,

including former employees of the company. Senior leaders, particularly women,

are regularly asked to provide referrals from their networks.

In

addition, a new program planned for launch focuses on engaging with Citi alumni.

Alumni will receive regular updates from leaders on knowledge, new developments

and opportunities at Citi. While the mission is broader than recruiting, there

is a belief that staying in touch with former employees, many of whom are on

extended career breaks, will be a powerful tool for attracting new employees or

referrals, particularly from women.

5.

Surface barriers and

biases. During this

phase, we work to surface, rather than drive underground, the fears, mindsets

and behaviours that work against reaching our aspiration. We might do this

through surveys and focus groups, and through individual conversations. It is

important to get a sense of things that stand in the way of meeting our

goals.

Treating

diversity on par with other business objectives makes a significant difference

and allows opportunity for real action. In this phase, we are getting good at

identifying barriers and intervening to offset their impact.

For most

of us, in this second phase we still see obstacles to reaching our ultimate

objective—an environment where supporting gender diversity is ingrained

within the very culture of our business.

Questions

we would encourage you to think about:

How do you

signal the importance of this issue to your organisation in the way you commit

your time, and in the conversations you have?

Do high

potential women inside your organisation or currently on career breaks have real

sponsors?

Can you

identify the top three priority areas where you and your top team need to

personally intervene?

‘Our

strategy is to stay ahead of the curve on talent, by building a culture that is

truly inclusive. I tell people that we shouldn’t rest until we reach

census levels–50/50. When I see hesitation or resistance, I know I’m

onto something. I find it energising!’

Andrew

Stevens, IBM

‘The

success of our strategy depends on having a vibrant workforce, with people who

understand and can connect with our customers and markets wherever we operate.

With more women in our leadership pipeline and senior executive ranks, we are

tapping into a much broader range of leadership styles, experiences and skills

to manage our business and achieve our goals.’

Mike

Smith, ANZ

‘Qantas

is an iconic brand. It’s about the legacy you leave and diversity is a key

part of that. This covers gender, indigenous, disability, age, sexual

orientation. If I do it right, Qantas will be much more rounded, more

representative for a national icon and much stronger for the next 90 years. If I

leave with the right diversity in place, then it’s a job well

done.’

Alan

Joyce, Qantas

‘The

key to changing behaviours has been our consistent focus across multiple

generations of the APS. There is now a groundswell of people leaving a legacy.

Its become part of our culture and now, is just the way we do

business.’

Annwyn

Godwin, Merit Protection Commissioner, Australian Public Service

Commission

‘We

know that a diverse workforce creates value and we need to ensure we reflect the

customers and communities we work with. NAB sees our focus on the advancement of

women as a never ending journey. Early progress has been pleasing, however, we

need to ensure we stay the course.’

Cameron

Clyne, NAB

‘Success

is about sustainable gender diversity, not just a few key roles filled at a

moment in time.’

Sue

Morphet, Pacific Brands

‘For

me, this is all about, how we build great leaders. It’s a broader shift.

How do people lead other people? How do you work with each individual to make

them successful? How do you create an environment which is inclusive, where

everyone can perform to their potential? That’s why this is so

important.’

David

Thodey, Telstra

‘We

need to make leadership appointments, not technical ones. It will require focus,

but it’s absolutely the right thing to do for the business. Our culture

and performance will be all the better for it.’

Grant

O’Brien, Woolworths

‘We’ve

been focused on building a strong inclusive culture for many years now to ensure

that we can attract and motivate the best talent possible, regardless of gender,

ethnicity, religion or sexual preference. This requires the courage to try new

things and challenge long held mindsets and unconscious bias. It also requires

unwavering commitment.’

Ian

Narev, CBA