The health and well-being of children in immigration detention

The health and well-being of children in immigration detention

Report to the Australian Human Rights Commission

Monitoring Visit to Wickham Point Detention Centre, Darwin, NT (October 16th – 18th 2015)

Professor Elizabeth Elliott AM MD MPhil MBBS FRACP FRCPCH FRCP Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Sydney Consultant Paediatrician, The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network (Westmead) Practitioner Fellow, National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia | Dr Hasantha Gunasekera MBBS DCH MIPH (Hons) FRACP PhD Senior Lecturer, Discipline of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Sydney Consultant Paediatrician, The Refugee Clinic, The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network (Westmead) |

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary and Recommendations

- Introduction

- Monitoring visit to Wickham Point Detention Centre

- Data Collection

- Results

- Health concerns regarding children

- Observations regarding the detention centre and environment with particular relevance to children: Wickham Point

- Information regarding the Nauru detention centre and environment with particular relevance to children

- Parent Evaluation of Developmental Status

- Mental Health Screening in children aged 8 years or more

- Risk of Post-traumatic stress disorder

- Hopefulness and despair

- Mental Health of children: interview results

- Children's drawings

- Summary and recommendations

- Appendix 1: Data collection methods and justification for screening tools used

- Appendix 2: Photos from visit to Wickham Point (Sand compound)

- Appendix 3. Illustrations from children in detention

- Appendix 4: Biographical notes of authors*

Executive Summary and Recommendations

Through observation, interview and formal testing, we have confirmed that closed immigration detention in Wickham Point and Nauru is harmful to the health and mental health of young children and youth. We know that harm increases with increasing duration of detention, and most of these children have been in prolonged detention for over a year. We also confirmed a mismatch between the burden of mental ill health problems, including post traumatic stress disorder and developmental risks, and the availability of readily accessible and appropriate specialist paediatric and adolescent psychiatric services for children resident at Wickham point. We were deeply disturbed by the numbers of young children who expressed intent to self-harm and talked openly about suicide and by those who had already self-harmed. The only appropriate management of this situation is removal of children from the toxic detention environment which is causing and/or exacerbating mental ill-health.

The children interviewed at Wickham Point, most of whom had spent several months in Nauru, are amongst the most traumatised children the paediatricians have ever seen. There was an evident lack of understanding by centre staff of the relationship between prolonged detention and post-traumatic stress disorder and the cumulative impact of one episode of trauma upon another. For example, some children had witnessed atrocities at home, survived a traumatic boat trip, had been moved between several onshore to offshore detention centres, were traumatised by the presence of uniformed guards and actions such as head counts and had palpable anticipatory trauma at mention of return to Nauru.

There was a mismatch between the level of mental health and the level of paediatric psychiatrists and psychologists with appropriate training in managing children. This must urgently be addressed.

Recommendations

We recommend that:

- All children be immediately removed from immigration detention facilities to community detention in mainland Australia or granted a bridging visa.

- Under no circumstances should any child detained on the mainland be returned to or transferred to Nauru.

- Nauru is an inappropriate place for asylum-seeking children to live, either in the detention centre or in the community.

Specific recommendations in relation to Wickham Point

We recommend that:

- Wickham Point should not be considered an alternative place of detention for children because the environment, educational opportunities, play and recreational and health services are inadequate for children.

- Health services be augmented:

- Augmented Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Child Psychology services are urgently needed.

- Access to primary healthcare and dental services must be improved.

- Referral to specialist paediatricians at Royal Darwin Hospital should be made for all children with significant ongoing medical issues.

- Play equipment and recreational opportunities be improved:

- Families and young children should be able to access the playroom at all times and not just for 1 hour during weekdays. This could be achieved by unlocking the doors and including windows to improve visibility from outside while maintaining the air conditioning.

- A range of age-appropriate toys should be available in the shop so that children can have their own toys to take back to their rooms.

- The oval should be made accessible to families in the Sand compound every day outside school hours. During school hours and in the evenings residents in Surf and Sun could have access.

- Children require additional spaces to ride their bikes and rules should be applied consistently by the Serco guards.

- A swimming pool should be installed given the health benefits, the extreme heat and the limited recreational opportunities.

- There be modifications to the build environment as follows:

- That consideration be given to creating a more appropriate environment for children in the Sand compound with less concrete and fencing.

- For families with children who require more than one room, connecting rooms should be made available so that the parents can adequately supervise their children in a safe environment.

- There be some modifications to food provided, as follows:

- Food needs to be made accessible outside of strict meal times for young children who tend to “graze” rather than sticking to strict mealtimes. There is bread and some fruit available in a communal fridge but only chips, biscuits, chocolates and instant noodles in the shop.

- We recommend consultation with a paediatric dietician to improve the variety and suitability of the food provided in the mess, also in the communal fridge and the shop.

- We suggest surveying parents and children regarding their children’s food preferences and needs, giving them some empowerment and choice.

- That with regard to Serco guards

- The 5am and 10pm headcounts for families with children should be discontinued due to the disruption to sleep and the fear that this generates.

- Serco guards should be educated regarding the enormous burden of mental health problems being experienced by the traumatised children living in detention.

- Serco guards should refrain from wearing their uniforms when dropping kids off to school or taking them on excursions given the stigmatisation that ensues.

- Serco should permit families and children some pocket money when they take excursions to purchase small items such as ice creams or drinks.

- That the management of Wickham Point surveys all families and children about how to improve the detention environment and thus provide them with some empowerment and choice. This could include questions about:

- Recreational activities

- Excursions

- Food in the mess hall, communal areas and shop

- Internet access

- Gym access

- Playroom access

- Accommodation

Introduction

Background to the visit

On February 11th 2015, the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) report - The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into children in immigration detention 2014 was tabled by the Attorney General in the Australian Parliament. [1] The Inquiry, led by President of the Human Rights Commission Professor Gillian Triggs, included data supplied by the Department of Immigration and its contractors, and information obtained during five public hearings (41 witnesses), interviews with 1129 children and families during 13 visits to 11 detention centres, and 239 public submissions. The report was pertinent to the period January 2013 to October 2014, spanning Labor and Coalition governments.

The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into Children in Detention

The overarching finding of the Inquiry was that prolonged immigration detention was both unlawful and harmful to the mental and physical health and well-being of children.

At the conclusion of the Inquiry (October 2014) 726 children had been detained for more than 14 months and 34% of those formally assessed had mental health problems deemed moderately severe to very severe (compared to an estimated 2% in the general population). In a 14 month period, the Department of Immigration recorded 128 cases of actual self-harm among children in closed immigration facilities. There was a pervasive atmosphere of despair and hopelessness: 38% of children said they were ‘always sad or crying’ and 21% were ‘always worried.’ Many had post-traumatic stress disorder manifest by flashbacks, nightmares and regression (onset of bed-wetting, stutter, and separation anxiety). Some exhibited developmental and/or growth delay; aggressive or oppositional behaviour; or symptoms consistent with Pervasive Refusal (elective mutism, food refusal, social withdrawal).[2][3][4][5]

The inappropriate physical environment in detention facilities, included inadequate housing and recreational or play facilities, fencing and guards; the toxic emotional environment, including maternal distress, self-harm and attempted suicide; deprivation of liberty; and restricted access to health care and education. Prolonged detention in this environment was deemed causal to the adverse child health and mental health outcomes reported. Conditions in remote, tropical, offshore detention facilities (Christmas Island and Nauru) were particularly unsuitable for children.

Key recommendations of the National Inquiry:

That:

- All children and their families be released into community detention or the community on bridging visas with a right to work.

- Legislation be enacted to ensure that children may be detained under the Migration Act for only so long as is necessary for health, identity and security checks.

- Assessment of refugee status be commenced immediately according to the rule of law.

- No child be sent offshore for processing unless it is clear that their human rights will be respected.

- An independent guardian be appointed for unaccompanied children seeking asylum in Australia.

- Children in immigration detention be assessed regularly using the HoNOSCA mental health assessment tool.

- Children currently or previously detained at any time since 1992 have access to government funded mental health support.

- Children and families in immigration detention receive information about the provision of free legal advice and access to phones and computers.

- Legislation be enacted to give direct effect to the Convention on the Rights of the Child under Australian law.

- A royal commission be set up to examine the continued use of the 1992 policy of mandatory detention, the use of force by the Commonwealth against children in detention and allegations of sexual assault against these children and to consider remedies for breach of the Commonwealth’s duty of care to detained children.

Monitoring visit to Wickham Point Detention Centre, Darwin

Purpose of the visit

The overall objective of the AHRC Visit to the Wickham Point Detention Centre in Darwin, NT was to monitor conditions in immigration detention and the well-being of detainees, including children and their families. During October 16th – 18th 2015 inclusive, four AHRC staff visited the centre, accompanied by two Consultant Paediatricians with experience in the health and well-being of asylum seeker and refugee children, Professor Elizabeth Elliott 1 and Dr Hasantha Gunasekera. 2 The focus of this report is on children and the detention environment.

Wickham Point Detention Centre

Wickham Point Detention centre is located 35 km (45 minutes) by road from Darwin in an isolated setting surrounded by bushland. Palmerston (15 km) is the nearest residential area. The centre was originally built as an ‘immigration detention centre’ to house adult males. On July 11th 2013, the entire facility was designated an ‘alternative place of detention’, permitting accommodation of families with children in addition to single adults, however, no substantial changes have been made to the facilities to accommodate the needs of children and families.

Children in immigration detention in Australia

At the time of the AHRC visit (October 16-18 2015), publicly available statistics (end September 2015) 3 indicated that there were 113 children in immigration detention throughout Australia and 92 children in immigration detention on Nauru. In addition, there were 409 children in community detention in Australia and 3,861 children living in the community on a bridging visa. On average, children had been living in immigration detention for 417 days, and 23% had been detained for more than 2 years.

Detainees at Wickham Point

During the visit there were 607 detainees at Wickham Point, including people seeking asylum, ‘Illegal Maritime Arrivals’, people who have overstayed their visa and people released from prison. There were 164 families with 76 children younger than 18 years. Some asylum seekers had been transferred from offshore or mainland centres. Of the 76 children detained at Wickham Point, 69 were the subject of interviews by the AHRC and 49 of these had been detained in Nauru for an average of 10 months prior to transfer for medical assessment or treatment. We interviewed the parents of 15 children who were born in detention.

Detainees are accommodated in three compounds – Sand, Surf and Sun. Single adult males are accommodated in Surf and men requiring increased monitoring live in the Sun compound. Single adult females and families are accommodated in the Sand compound, which was originally designed for single adult males.

Data Collection

Detention Facilities and Environment

During the AHRC visit, 127 children (aged ≤18 years) and/or their parents were interviewed using a standardised questionnaire. They belonged to the following ethnic/language groups: Arabic; Bengali; Burmese/Myanmar; Farsi/Persian; Indonesian; Mandarin; Nepali; Rohingyan; Somali; Tamil; and Vietnamese.

Information was requested on the country of origin of families; the length of time and place(s) of immigration detention; the composition of families, including children’s ages and gender; concerns about the health, mental health and education of children; access to services; safety concerns; and environmental conditions in both Wickham Point detention centre and on Nauru. Informed written consent to collect and report de-identified information and direct quotes was sought with the assistance of a professional interpreter, who was present during the interviews (apart from two cases where the interview had to be done with phone interpreters).

Child development and mental health

Details of the screening tools used to assess child development and mental health are shown in Table 1. For children younger than 8 years parents provided information in response to 10 questions comprising the Parental Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS).[6] Permission to use this tool and translated PEDS questionnaires was provided by the Australian copyright holder, the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. This is a validated screening tool used to identify parental concerns regarding their child’s development and to guide additional assessment and management. Professor Elliott and Dr Gunasekera have been trained to administer PEDS. Children above 6 years of age were interviewed using the 10-item Child Trauma Screening Questionnaire (CTSQ) [7] to assess their risk of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. In children aged over 8 years the 2 question Hunter Opinions and Personal Expectations Scale (HOPES) [8] was used to determine children’s level of hopefulness, which has been shown to correlate with the level of resilience to current adversity. The longer Snyder Hope Scale was used in a few children (data not reported).4 At the request of some of the older children one group interview was conducted with a paediatrician and an AHRC staff member.

Table 1.

Characteristics of screening tools used to assess children | ||

Age | Tool | Validation |

Children who had not had their 8th birthday | Parental Evaluation of Developmental Status | Revalidated in 2012: Test re-test reliability 94% agreement Sensitivity = 86% Specificity = 74% |

Children who had had their 8th birthday | Child Trauma Screening Questionnaire | At 6 months: AUC = 0.78 (p<0.001) Sensitivity 82% (95%CI = 59-100), Specificity 74% (95% CI = 66-83) |

Snyder Child Hope Scale | It shows internal consistency, is relatively stable over retesting and exhibits convergent, discriminant and incremental validity | |

Hunter Opinions and Personal Expectations Scale | 2 items taken from 12 (scored 0-4 according to how given statements describe the child with the least hopeful or most despairing response scoring 4) These 2 correlated with other questions and also with anxiety and depression | |

Results

Health concerns regarding children

Parents reported many concerns regarding their own and their children’s health. Examples include: reports of recurrent abdominal pain, headaches, nausea, vomiting, poor feeding, poor sleeping and poor weight gain in young children. Some had developed nocturnal enuresis or encopresis. A 12-year old had chronic hypertension. One child, with a metabolic disorder diagnosed at birth in his homeland, had not yet seen a paediatrician in Australia. One child requiring genitourinary surgery had been seen at Royal Darwin Hospital and surgery was planned for 2016; another with a blocked tear duct has not seen an ophthalmologist. One child acquired typhoid while in Nauru; one is receiving prophylactic treatment for TB. Several allegations of sexual abuse are being investigated. One child with autistic spectrum disorder requires early intervention; a 2 year old with no speech needs audiology, speech pathology and paediatric assessment; a child with cervical lymphadenopathy needs investigation; and a child with developmental delay requires paediatric assessment.

Observations regarding the detention centre and environment with particular relevance to children: Wickham Point

Table 2.

Wickham Point | ||

|---|---|---|

Duration of stay | Average 9 months; range 3 - 18 months. | |

The detention centre location | Rural location, 35km from Darwin, surrounded by bushland, nearest residential town 15km, tropical climate | |

Family Accommodation | The detention centre is dominated by concrete and high fencing, which is completely inappropriate for children, particularly young children. As there is concrete and metal throughout the compounds, it is exceedingly hot. Families and children live in the Sand compound Two story buildings with multiple identical rooms (3.8 x 4.7m) Air-conditioned Up to 4 per room in bunk bedding (additional children would be housed in the adjacent room- no connecting rooms available) Ensuite bathroom Small bar fridge | |

Play areas | Limited space for play near accommodation with small playground areas with soft floors exposed to the sun during the day. We did not see any children playing there during our visit. New children’s play room opened just before our visit is air conditioned and contains some new toys for small children. Limited range of toys for all ages. Limited access to play room. The notice on the door and parents reported that it is open for only one hour per weekday 1-2pm. Poorly maintained/cleaned (e.g., a large sheet of plastic on floor that may pose a risk for young children). Untidy, unkempt. “We are allowed in only twice per week.” Mother child 5y “Inadequate size to accommodate all children in air conditioning. Although intended for infants and young children, “the older kids play in the playroom.” Mother of children 5, 9, 10y. “There is only one room. Only between1-2pm. I hour per day. The room is sometimes used for other activities e.g. English classes. It only opened two weeks ago. Previously we had an unpleasant room – very cramped – no room to play.” Mother of children 2, 5,6y. | |

Recreation and sport | Large computer room to service Sand Compound and library. Air-conditioned, but restricted access 1 hour/day internet access Gym available to all detainees. Older boys complain that access is limited: the gym closes at 5pm, less than one hour after they return from school. Bikes are available for loan by children but restricted in number and the area in which to ride is limited. Inconsistent approach by guards regarding where children can ride. Full sized oval separates Sand and Sun compounds. Surrounded by high fencing. Access limited to particular days/times to prevent mixing between families and single men. Often empty during our visit. No organised physical activity or sport. Children complain that some activities are scheduled during school time. Organised recreation activities occurred “Three times in 7 months (including during our visit) they brought slides and a water fountain. There are not games or sport organised.” | |

Excursions | Limited number and range of excursions (1 per 2 months). Some exclude children. Presence of guard is stigmatising. Interventions from guards reported (e.g., preventing detainee speaking to local resident). A reported incident of guards eating ice-cream in front of children on an excursion. When children asked could they have one they were told they can buy one themselves, but detainees have no access to money. One Chinese mother and baby were taken to the deep (2m) swimming pool but not supplied with swimming costume, whereas adults reported being taken to a toddler pool. “Only one excursion in eight months to a play group.” Mum, child aged 2y | |

Nutrition | Meals provided in separate family/single women and single men’s mess, all open at the same time. Reasonable quality food but repetitive and many children don’t like food. Lack of recognition of the pattern of eating of young children: parents are unable to take food to the room to feed children between meals. As a result many eat poor quality food - noodles and biscuits from the shop. One microwave is shared by 400 people. Some children refuse to eat in the mess and mothers smuggle food out. “They don’t like the food. It’s difficult to feed them.” Mother children 6m, 2, 5,7y.” | |

Health care | The clinic was modern, clean and well-equipped, however the International Health and Medical Service report high volume demand exceeding capacity (services recently cut from 24/7 to 9am-5pm. Two GPs and 7 primary health care nurses on site daily, take booked appointments. Written request required to see a doctor/nurse submitted. Requests are triaged. Children get priority but reports of a two week wait with no guarantee of seeing a doctor were frequent and affirmed by IHMS. Critical shortage of child-specific services including paediatrician, child psychiatrist and child psychologist. Mismatch between mental health requirements and access to services e.g., many children with severe mental illness are seen at Melaleuca Torture and Trauma Service in Darwin without access to child psychology/psychiatry. There is a 3 week waitlist to go to Melaleuca. The child/adolescent psychiatrist servicing Wickham Point is on maternity leave. Tele-psychiatry services currently provided by Dr Jonathan Williams from Perth. Two psychologists (one with paediatric training) are fully booked. Paediatricians at Royal Darwin Hospital reported only approximately 10 referrals in a year. Up to 15 off-site medical appointments each day. Antenatal and obstetric care and confinements are managed at Royal Darwin Hospital. Many women are deemed high obstetric risk due to small stature, Diabetes Mellitus, Female genital mutilation. Dentist and hygienist 3 days per week fully booked – dental pain is common, the legacy of poor dental care. More services are needed. Adult psychiatrist visits 5 times per month. “I have no confidence in the health service here. One child had problems with noisy breathing. They were told ‘no problem’ but ultimately they were taken as an emergency to Melbourne.” Mother children 2m, 2y | |

Bathrooms | No specific complaints | |

Physical environment | Fences dominate Wickham. Tall, parallel wire fences with a sterile zone. The perimeter fence is electrified but only activated adjacent to the Sun compound. Restricted access from Sand to oval, mess (via gates with guard) and no access to Sun compound. Security screening at entrance. SERCO guards at all access points. Tropical – hot, wet climate | |

Religion | There is one multi-faith room but complaints that it is dominated by one group and their icons etc. Lack of creativity in addressing this. Limited capacity to attend church outside the compound. “I was allowed to go to church twice in 7 months - it’s a 20 minute drive.” Father of three. | |

Safety | The key safety issue at Wickham Point is risk of self-harm, Numerous parental and child reports of thoughts of self-harm or suicide. Data from Wickham Point on self-harm have been requested from the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. “Physically they are safe, but mentally they are not. All of the time they ask why are we here so long? Are we going to stay forever? What’s going to happen to us?” Father of children aged 5, 9, 10y. | |

Treatment by guards | Range of responses, mostly ‘good’ but some reported incidents of poor treatment. “He doesn’t even ask my name, he asks what is your number?” Boy, 9y Some reports of children frightened by guards in the centre. Reports of use of handcuffs for transfers. “Two weeks ago I was going to Melaleuca (for treatment) but they wanted to put me in handcuffs. I refused because ‘What would people think? I am not a criminal.” Boy 18y with mental health problems. | |

Education | School program commenced January 27, 2011 for all children aged 5 – 15 years. NT Education Department currently allows children aged 4- 17 years to enrol in pre-school or school, however there are reports of 4 year old children not attending pre-school. “There is no preschool. The paediatrician says he needs stimulation but he’s too young for school.” Mother of child 4y. Children attend school in Darwin, a 45 minute drive by bus (7.30am-430pm). Escorted by guards. “They love school. Otherwise they would go mad.” Father, children 9y, 10y. Reports of exclusion, bullying, stigmatization at school. One boy teased at school sad they say ‘You’re from detention, you’re dirty, I don’t want to play.” Boy 9y. “I want to go free – I want my mum and dad and little brother to take me there. I don’t like officers.” Girl, 7y. Her mother adds “She is meant to go to school. Year 1. But she doesn’t want to go.” Many children unable to concentrate at school due to PTSD. ”The teachers are really helpful but I’m distracted by thoughts of the past.” Boy 16y Older children said school highlights the disadvantage they face as detainees, notably lack of freedom of movement. “My friends say come and play (after school). I say I can’t. I’m in detention.” Boy 10y. Lack of vocational education or training for older children. “There is nothing for me to do here. I have lost three years of education. Since 17 years (age) I have been in Christmas Island. “ Boy 19y. | |

Information regarding the Nauru detention centre and environment with particular relevance to children

Many of the children and families interviewed had spent time in Nauru and provided information about detention there.

Table 3.

Nauru | |

|---|---|

Duration of stay | Average 10 months; range 3 – 17 months. |

The detention centre | Republic of Nauru. Remote equatorial location, tropical climate, English is a second language Phosphate mining. |

Description of Nauru | Universally parents and children provided a negative response to the request to briefly describe Nauru, for example: “Depression for all people. You feel there is no hope, it’s the end of the future. “ “Hell, nightmare.” “Worst place in the world.” ”Tent very hot.” “Toilets far away.” “Nauru is hell on earth. Before we die we have seen hell.” “Those who have been to Nauru have experienced death.” “It’s very hard to have kids in Nauru – the heat, toilet facilities, the tent. Sometimes it’s hard to find water. The food is not good. Sometimes we have to walk in heavy rain for food and toilets. Very humid. There are rocks on the ground – it’s very hard to walk.” |

Family Accommodation | From parents we heard universal criticism of the tented accommodation particularly the heat, lack of air conditioning, privacy, lack of proximate bathroom facilities and lack of space for children to play. For children the extreme heat was a major complaint. Families and children live in tents with up to 5 families (18-20 people) with flimsy partitioning – no privacy, noisy. Most report no air-conditioning or one small, ineffective unit for the whole tent. Extraction or ventilation fans are provided to families with babies but are often malfunctioning. Hot, humid, temperatures in tents. Snakes, cockroaches, mosquitos, mice, rats reported. “Mice, cockroaches, crabs. 55 degrees inside the tent.” No water/basin in tent e.g. to wash hands after changing nappy or wash children who refuse to go to shower block. Limited space for play or exploration within accommodation No capacity to store food in tent. |

Bathrooms | Safety was a major concern of women and children and men usually accompanied women and children to the bathrooms. Bathrooms located between 50 to 100 metres from tents. Almost universally, people complained about the duration of showers and the water shortages. Limited shower 2 minutes (if the guard is nice, otherwise shorter) “Sometimes there is not water for showers for a few days.” “Not enough toilets (8 for 800 men).” “Toilets often dirty. No child size toilets.” “If there is water, we can use washing machines every two weeks - otherwise it might be once every month.” |

Guards | Range of descriptions – some described guards as often/always bad. One man said “They are the worst security guards. All are ex-soldiers, some had been in Iraq. They were all harsh and treated us as if we were in a battlefield e.g. they timed the 2 minute showers. Mostly we didn’t have time to rinse out the shampoo.” |

Nutrition | Food sufficient but repetitive. |

Safety | Universal concerns about safety even within the compound. Most reported they would not leave the compound even though it is now open access. As above most women/children would not go to toilet/shower block alone. On man said that since the policy change to allow free access his friends in Nauru report “No one is going outside because it is not safe. Dangerous after 6pm. Poor control by police – assault, theft, alcohol, rape.” “It’s a very small country. There is nowhere to go, nothing to do.” “There is no place to go – only rocks on both sides. 4km on one side, 6km the other direction. There is no place to go.” |

Education | Complaints that some local teachers are hard to understand. |

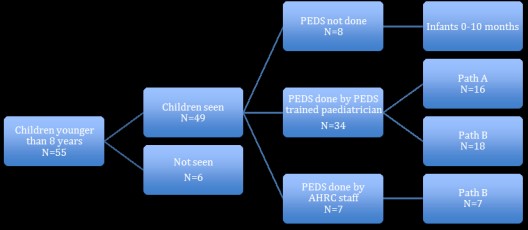

Parent Evaluation of Developmental Status

Figure 1 shows the number of children screened using the Parental Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS). We assessed the majority (49/55 = 89%) of children younger than 8 years known to be in the centre. For 34 of these 49 children, PEDS was administered by a senior paediatrician with specific individualised training on the administration of PEDS by a senior PEDS trainer. All children whose families were interviewed by the AHRC team but who did not have the PEDS administered were aged 10 months or younger.

Figure 1. Flow chart of screening for children aged less than 8 years with PEDS

Table 4 shows the results of PEDS screening. Of the 34 children assessed by a trained paediatrician, 47% were found to be at the highest developmental risk (Pathway A). To reach this level of risk on the PEDS, a parent must report at least 2 concerns that are predictive of adverse developmental outcomes. We found 8/34 = 24% with 2 predictive concerns, and another 24% with 3, 4 or 5 predictive concerns (more than twice the threshold for the highest level of developmental risk). AHRC staff administered a small number of PEDS (N=7) when no paediatrician was available. PEDS administered by AHRC staff also showed that the children were at moderate developmental risk.

Table 4. Parental Evaluation of Developmental Status (N=34)

Children | Children | Children | ||||||||

# Predictive concerns | N | (%) | # Other concerns | N | % | PEDS Pathway | N | % | ||

0 | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | 9 | (26.5) | A | 16 | (47.1) | ||

1 | 18 | (52.9) | 1 | 10 | (29.4) | B | 18 | (52.9) | ||

2 | 8 | (23.5) | 2 | 8 | (23.5) | C | 0 | |||

3 | 2 | (5.9) | 3 | 3 | (8.8) | D | 0 | |||

4 | 5 | (14.7) | 4 | 1 | (2.9) | E | 0 | |||

5 | 1 | (2.9) | 5 | 3 | (8.8) | |||||

TOTAL | 34 | (100.0) | 34 | (100.0) | 34 | (100.0) | ||||

Path A = Children at high developmental risk (2+ predictive concerns); Path B = Children at moderate developmental risk (1 predictive concern); Path C = Non-predictive concerns; Path D = Parental difficulty communicating; Path E = No concerns.

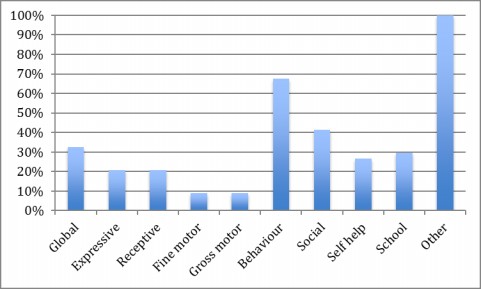

Figure 2 shows the proportion of parents who reported concerns for individual attributes covered in the PEDS. The majority of parents responded “no concerns” to most questions. This highlights the fact that parents were not simply responding ‘yes’ to every question. However, they indicated concerns about behavioural disturbance (68%), social skills (41%), and 100% voiced grave concerns about their children being in the detention environment, particularly their mental health state. Nevertheless, the concerns that parents did raise were the specific concerns that have been found to be predictive of developmental risk.

Therefore, 100% of the children assessed using PEDS were found to be in the highest two categories of developmental risk (Pathways A and B), higher than any published PEDS results anywhere in the world. 9 These findings are consistent with other parental reports of health and developmental concerns in traumatised children in immigration detention and specifically highlight the developmental risk for these vulnerable children. The two senior paediatricians assessing these children also received reports of children losing developmental skills (e.g., deteriorating speech and behavioural disturbance) which is very rare, and signifies significant trauma. Many children demonstrated other typical features of distress (e.g., developing nocturnal enuresis, stuttering, headaches, recurrent abdominal pain, anorexia, constipation and encopresis)[9],[10],[11],[12]

Figure 2: Proportion of children whose parents reported concerns by PEDS question (N=34)

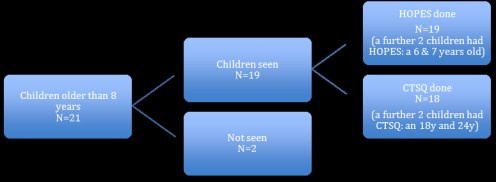

Mental Health Screening in children aged 8 years or more

The flow chart for screening children aged 8 years or more for risk of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and ‘hopefulness’ is shown in Figure 3. Both the Childhood Trauma Screening Questionnaire (CTSQ) and the Hunter Opinion and Personal Expectations Scale (HOPES) were administered to 18 (86%) of 21 eligible children.

Figure 3. Mental Health screening in Children aged 8 years or more

Risk of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

The Childhood Trauma Screening Questionnaire (CTSQ) was administered to 18 of the 21 eligible children aged between 8 and less than 18 years known to be living in the centre plus an additional 2 children aged 6 and 7 years (total = 20). All these children had lived in Nauru for between 3 and 17 months before transfer to Wickham Point for medical care. The traumatic event identified in the questions posed to children was detention in Nauru.

Of the 20 children who completed the questionnaire, 19 (95%) scored 5 or more, putting them in the ‘clinical’ range signifying risk for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.[13],[14],[15],[16] The other child scored 4/10, which is just outside the clinical range. The number and proportion of all children who responded ‘yes’ to individual questions on the CTSQ is shown in Table 5.

In addition to the ‘yes’/’no’ answers they provided to the CSTQ (Table 5), children often elaborated. Direct quotes from children with a range of ages are shown in Table 6.

Table 5.

Childhood Trauma Screening Questionnaire (N=20)* | ||

Question | “Yes” | |

N | (%) | |

| 1. Do you have lots of thoughts or memories about Nauru? | 20 | 100 |

| 2. Do you have bad dreams about Nauru? | 20 | 100 |

| 3. Do you feel or act as if Nauru is about to happen again? | 16 | 80 |

| 4. Do you have bodily reactions (such as fast-beating heart, stomach churning, sweating and feeling dizzy) when reminded of Nauru? | 15 | 75 |

| 5. Do you have trouble falling or staying asleep? | 16 | 80 |

| 6. Do you feel grumpy or lose your temper? | 13 | 65 |

| 7. Do you feel upset by reminders of Nauru? | 20 | 100 |

| 8. Do you have a hard time paying attention? | 17 | 85 |

| 9. Are you on the “look out” for possible dangerous things that might happen to yourself and others? | 17 | 85 |

| 10. When things happen by surprise or all of a sudden, does it make you “jump”? | 13 | 65 |

* One eligible child aged 14 years did not complete the CTSQ

Table 6.

Comments from children responding ‘yes’ to CTSQ questions | ||

Question | Child | Illustrative Comments [17] |

1 | 7y girl 9y girl 15y girl | “For one year refused to go to the shower, washed in the tent.” “All the time. We have to be in the tent and it’s very hot.” “When I think about the rape that is happening in Nauru I think it will happen to me.” |

2 | 6y boy 7y girl 9y girl 9y boy | “Somebody is chasing me and trying to grab me from behind and scare me. Then I run after my Mum and she is not there.” “Sometimes I dream about the cheaters there who steal things.” “In the nightmare I see my father and mother crying.” “I dream about bad things – about cockroaches coming on my face, all over my body.” |

3 | 9y boy | “I am scared in my room every night at 10 pm when they walk and open the door for the head count. I think someone is going to take me away.” |

4 | 9y girl 17y boy 7y girl | “I feel fearful. My heart starts beating fast when I think about the heat.” “I get palpitations and shivering.” “Sometimes I feel like vomiting or I vomit.” |

5 | 10y boy 15y girl | “I am really scared to sleep. I have my Dad with me always.” “I don’t sleep much. Sometimes only from 4 to 6 am.” |

6 | 7y girl | “She says I don’t like you, you are a liar, go away (to parents). Crying, shouting, every day angry, scratches mother.” |

7 | 7y girl 9y boy | “Wets the bed when she has dreams of Nauru or talks about Nauru.” “Every night I say to my Mum you are lying. You said we were going to Australia.” |

8 | 9y boy 10y boy 15y girl 16y boy | “In my heart I feel alone without happiness.” “When I am at school I am happy but back in detention I feel sick.” “At school the difference between me and them is more obvious.” “At school I think about the future and get sad. Other students don’t understand.” |

9 | 10y boy 16y boy | “I worry about the army.” “I feel like someone is coming from behind to hurt me.” |

10 | 10y boy 16y boy | “All the time.” “Yes, even when the officers shout and yell.” |

Hopefulness and despair

In situations of adversity high levels of hopefulness for the future correlate with good mental health and resilience. [18],[19],[20] Conversely, high levels of despair correlate with risk for anxiety and depression. Two questions from the Hunter Opinion and Personal Expectations Scale (HOPES) were used to assess hopefulness and despair in 19 children and youth aged 8 years to less than 18 years plus 2 aged 18 and 24 years. Scores were obtained for two questions (one positive/representing hopefulness, one negative/representing despair). Scores for these two questions have been shown to correlate with the full score.

More than 95% of the children and adolescents interviewed received the highest possible score for hopelessness (Table 3). All children reported some degree of despair and 90% received the highest possible score for despair.

Table 7. Hunter Opinion and Personal Expectations Scale: two questions (N=21)

Question | Responding children | ||||

Hope question | “Response describes me” | Number | (%) | ||

I generally believe that I will get what I want out of life | Extremely well | 0 | (0.0) | ||

Very well | 1 | (4.8) | |||

Moderately well | 0 | (0.0) | |||

NOT very well | 0 | (0.0) | |||

NOT at all* | 20 | (95.2) | |||

Despair question | |||||

Even when things go right, I often fear that my future is NOT under my control | Extremely well* | 18 | (90.0) | ||

Very well | 1 | (5.0) | |||

Moderately well | 1 | (5.0) | |||

NOT very well | 0 | (0.0) | |||

NOT at all | 0 | (0.0) | |||

Not asked | 1 | N/A | |||

* High scores for responses to despair questions on the HOPE scale are highly predictive of anxiety and depression and high scores for responses to hope questions predict good mental health and resilience.

Mental Health of children: interview results

There were numerous reports of concerning child mental ill-health by parents and children. Children as young as nine years of age are receiving medication to help them sleep. The children interviewed are amongst the most traumatised children the paediatricians have ever seen. There was an evident lack of understanding by centre staff of the relationship between prolonged detention and post-traumatic stress disorder and the cumulative impact of one episode of trauma upon another. For example, some children had witnessed atrocities at home, survived a traumatic boat trip, had been moved between several onshore and offshore detention centres, were traumatised by the presence of uniformed guards and actions such as head counts, and had palpable anticipatory trauma at the mention of return to Nauru.

There was a mismatch between the level of mental health and the level of access to paediatric psychiatrist and psychologists with appropriate training in managing children. A request has been made to the Department of Immigration and Border Protection for the data on actual self harm by children in the Wickham Point. Many of the children and young adults had either self-harmed or talked about self harming.

The extent of the distress is illustrated in the quotes below.[21]

“She has no friends. She cries all the time and says I want to go from here. She has cut herself with a razor on her chin, face, chest. She eats poorly, has daily headache and tummy pain and poor weight gain. Every night she wakes up and screams that someone (8 officers) is coming to take her back to Nauru. She has seen a counsellor in Darwin.” Mother, girl 7y. ’

“He is depressed, scratches himself till he bleeds. Bites his nails. Doesn’t associate with anyone, including family. He saw the mental health team once and was told he is in need of ‘big attention’ but he has seen no one yet. That was 2 months ago.” Mother of 16 year-old.

“His friend ate razors and got out of detention into the community. He says If I jump from the balcony, eat sand, drink shampoo maybe I will get out. The psychologist said it’s normal. “Mother of boy 9y.

Constant reminders of their return to Nauru are distressing.

“There is no one here to help us get what we want. My case manager I saw the other day said the high court case will possibly be lost - don’t think there is a 100% chance to win. Your family has no problems – you can go back to Nauru. She really made me sad.” Boy, 19y.

“When I think about the rape that is happening in Nauru I think it will happen to me. I miss my friends. I am staying here – we came in the same boat but they are free. Sometimes I think if I hurt myself we will get out.” Girl 15y.

“Hell is a hot place and it was hot in Nauru. In hell you have no quality of life. In hell you have people tormenting you.” Father of children aged 2 years and 2 months.

“In Nauru there were all kinds of insects – spiders, scorpion, cockroaches, rats, lizards. Once I found a dangerous spider amongst the toys. Also big crabs – a different type from Christmas Island – under the bed of my child. My child was playing with cockroaches – he had no other toys.” Father, boy aged 2 years.

“I came here for one thing. We were running from the police. They took my Mum and my grandmother (for 10 days). They put a gun to my Dad’s head and took him (for 2 months). I saw that happen.” Boy 9y.

“Two of her friends jumped off the building and got broken hips and legs. They were sent to the community. She is talking about doing the same thing. She has been seen (by a counsellor in Darwin) and mental health here but says ‘talking to them doesn’t change anything for me.’ She has no medication, no psychiatrist.” Mother of girl, 15y.

When interviewed independently that girl reported “I am at the end of the line. I’m really negative. I’m at the end. I feel maybe I should kill myself to end it all.“ Girl 15y

Children and parents were asked what they would like the AHRC to report on their behalf. Some of the responses are listed below.

“The Prime Minister of Australia says he is saving our lives but at the same time he is killing us” Boy 16y.

“I have not come to this country to teach my children how to commit suicide.” Father of three teenage boys.

“Please help us! Think about we’re your kids. Think what happened past to us. When I came in this way I was 12 and now I’m 14 and half. So that means I been in detentions two years. (Please help us!) We didn’t do anything in this country so why we should be in here two years. I think nothing can help us expect visa so we can be free and do whatever we want!” Boy, 14 y.

“My message: I just don’t want to see ‘fence’ in my life anymore. No ‘Fence’ of any kind.” Boy 17y.

“You can do anything to me, but don’t return me to Nauru.” Boy 17y.

“I’m prepared to stay here but not to return to Nauru.” Boy 16y.

“I think for dying. I don’t see any future. I feel sadness I see no future.” Boy 18y.

“I keep to myself, watch movies. I only go out once a day. I have observed that my friends either feel worse on medications or end up with side effect – zombie. “ Boy 24y.

“I honestly don’t see and future. I wish I had died in the ocean.” Boy 15 years.

The findings in this report are entirely consistent with other reports published about children in detention in Australia and elsewhere. [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27]

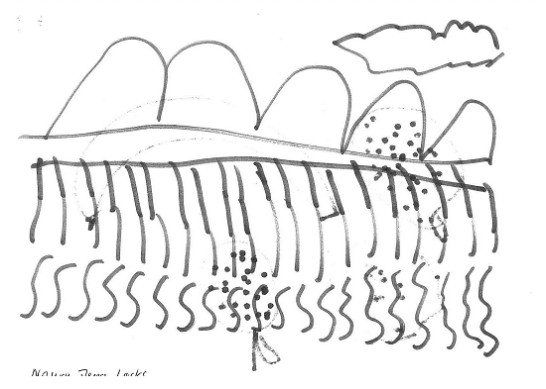

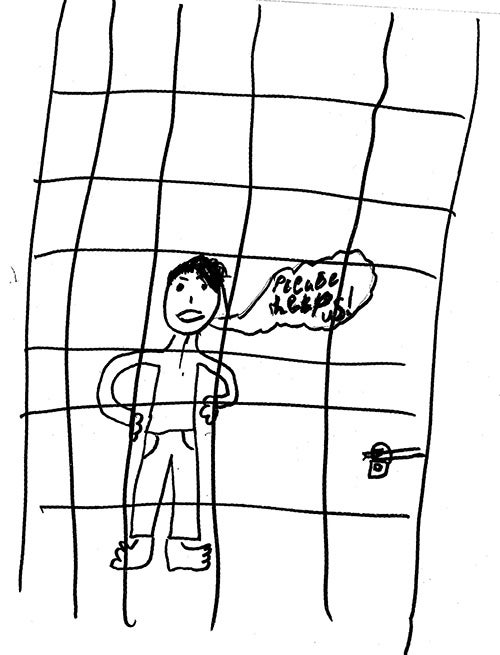

Children’s Drawings (Appendix 3)

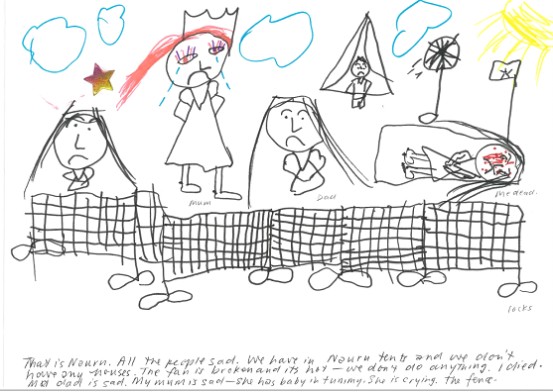

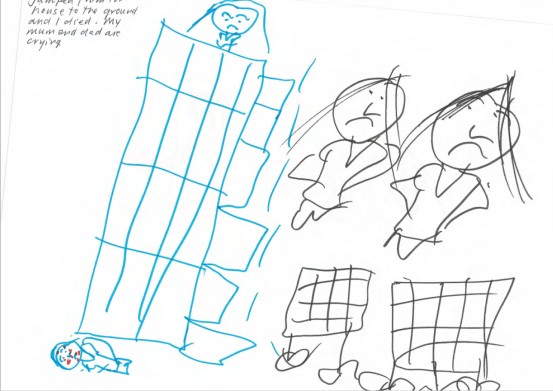

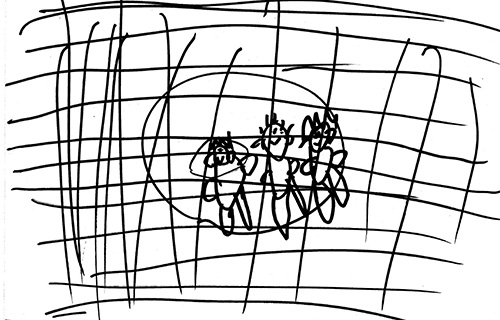

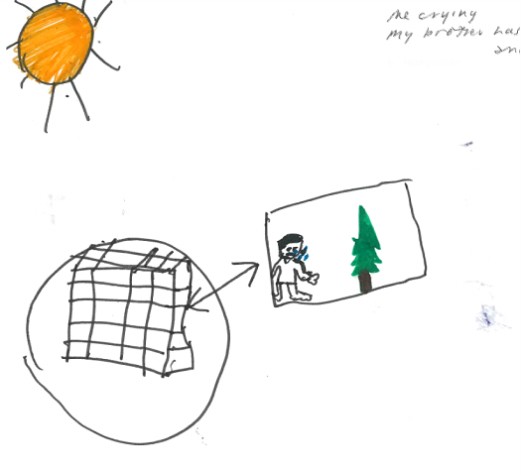

Children were asked to draw a picture of their life in or their family. These drawings were very revealing, some extremely distressing. The drawings were dominated by pictures of boats, fences, tents and crying or sad people. Some examples are shown in Appendix 3.

One highly traumatised girl, aged 7 years who had self-harmed did several drawings while her parents were being interviewed. The first (Figure 1, Appendix 3) depicted a sad “Me in the boat.” The second 9Figure 2, Appendix 3)depicted the hills of Nauru with a dominant “Fence” with “locks.”

In a third drawing (Figure 3, Appendix 3) she depicted life in Nauru, explaining. “That is Nauru. All the people sad. We have in Nauru tents and we don’t have any houses. The fan is broken and it’s hot. We don’t do anything.” That is “Me dead. I died. My dad is sad. My mum is sad – she has a baby in tummy. She is crying.” That’s “The fence with locks.”

Her last drawing (Figure 4, Appendix 3) features the compound, fences and locks at Nauru. She pictures herself both at the top of her house and on the ground, describing. “I jumped from the house to the ground and I died. My mum and dad are crying.”

Children often drew themselves behind bars. A boy aged 6 years drew “My dad, me and my mum behind the fence at Nauru. (Figure 5, Appendix 3). This child wrote his boat number on the drawing.

A boy aged 10 years drew a picture of the fence (Figure 6, Appendix 3) and “Me crying. My brother has problem with his kidney and penis.” His sibling is awaiting a surgical procedure.

A boy aged 9 years who drew himself behind bars said “This is my life. Please help us.” (Figure 7, Appendix 3). This boy wrote his boat number on his drawing.

Summary and recommendations

Through observation, interview and formal testing, we have confirmed that closed immigration detention in Wickham Point and Nauru is harmful to the health and mental health of young children and youth. We know that harm increases with increasing duration of detention, and most of these children have been in prolonged detention for over a year. We also confirmed a mismatch between the burden of mental ill health problems, including post-traumatic stress disorder and development risks, and the availability of readily accessible and appropriate specialist paediatric and adolescent psychiatric services for children resident at Wickham point. We were deeply disturbed by the numbers of young children who expressed intent to self-harm and talked openly about suicide and by those who had already self-harmed. The only appropriate management of this situation is removal of children from the toxic detention environment which is causing and/or exacerbating mental ill-health.

Recommendations

We recommend that:

- All children be immediately removed from immigration detention to community detention in mainland Australia or granted a bridging visa.

- Under no circumstances should any child detained on the mainland be returned to or transferred to Nauru.

- Nauru is an inappropriate place for asylum seeker children to live, either in the detention centre or in the community.

Specific recommendations in relation to Wickham Point

We recommend that:

- Wickham Point should not be considered an alternative place of detention for children because the environment, educational opportunities, play and recreational and health services are inadequate for children.

- Health services be augmented:

- Augmented Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Child Psychology services are urgently needed.

- Access to primary healthcare and dental services must be improved.

- Referral to specialist paediatricians at Royal Darwin Hospital should be made for all children with significant ongoing medical issues.

- Play equipment and recreational opportunities be improved:

- Families and young children should be able to access the playroom at all times and not just for 1 hour during weekdays. This could be achieved by unlocking the doors and including windows to improve visibility from outside while maintaining the air conditioning.

- A range of age-appropriate toys should be available in the shop so that children can have their own toys to take back to their rooms.

- The oval should be made accessible to families in the Sand compound every day outside school hours. During school hours and in the evenings residents in Surf and Sun could have access.

- Children require additional spaces to ride their bikes and rules should be applied consistently by the Serco guards.

- A swimming pool should be installed given the health benefits, the extreme heat and the limited recreational opportunities.

- There be modifications to the build environment as follows:

- That consideration be given to creating a more appropriate environment for children in the Sand compound with less concrete and fencing.

- For families with children who require more than one room, connecting rooms should be made available so that the parents can adequately supervise their children in a safe environment.

- There be some modifications to food provided, as follows:

- Food needs to be made accessible outside of strict meal times for young children who tend to “graze” rather than sticking to strict mealtimes. There is bread and some fruit available in a communal fridge but only chips, biscuits, chocolates and instant noodles in the shop.

- We recommend consultation with a paediatric dietician to improve the variety and suitability of the food provided in the mess, also in the communal fridge and the shop.

- We suggest surveying parents and children regarding their children’s food preferences and needs to give them some empowerment and choice.

- That with regard to Serco guards

- The 5am and 10pm headcounts for families with children should be discontinued due to the disruption to sleep and the fear that this generates.

- Serco guards should be educated regarding the enormous burden of mental health problems being experienced by the traumatised children living in detention.

- Serco guards should refrain from wearing their uniforms when dropping kids off to school or taking them on excursions given the stigmatisation that ensues.

- Serco should permit families and children some pocket money when they take excursions to purchase small items such as ice creams or drinks.

- That the management of Wickham Point surveys all families and children about how to improve the detention environment and thus provide them with some empowerment and choice. This could include questions about:

- Recreational activities

- Excursions

- Food in the mess hall, communal areas and shop.

- Internet access

- Gym access

- Playroom access

- Accommodation

Appendix 1: Data collection methods and justification for screening tools used

Interviewers (one of the following):

Professor Elizabeth Elliott AM MD MPhil MBBS FRACP FRCPCH FRCP

Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Sydney

Paediatrician, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead (pro bono)

Dr Hasantha Gunasekera MBBS DCH MIPH (Hons) FRACP PhD

Senior Lecturer, Discipline of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Sydney

Paediatrician, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead (pro bono)

Sarah Dillon

Australian Human Rights Commission Policy Officer

Anna Nelson

Australian Human Rights Commission Policy Officer

Parental Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS)1,2

This is a 10-item scale where parents report concerns with their children’s development, health and wellbeing. PEDS is the standard tool used in the personal health record (or “Blue book”) for all NSW children. The PEDS screening tool was developed by Dr Frances Page Glascoe PhD (Professor of Pediatrics at Vanderbilt University). Permission to use PEDS was granted by the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne. Translations of the PEDS questions were provided in PDF form from the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne. Translated versions of the PEDS were provided to the literate parents to read and given to the interpreters to ensure they used the correct wording.

Translated PEDS were available in the following languages:

- Arabic

- Burmese

- Farsi

- Indonesian

- Mandarin

- Nepali

- Somali

- Vietnamese

PEDS has been validated against standard psychometric tests. PEDS has published sensitivity of 91 to 97% and specificity of 73 -86%. PEDS was re-standardised in 2012 on a nationally representative sample of 47,531 families across the United States of America with children aged 0 to 11 months (N=13,523) through to 7 years 11 months (N=913). Test re-test reliability on 193 children showed 94% agreement in PEDS paths and parent’s concerns. Inter-rater reliability was established on 355 children for both categorizations of concerns (95% agreement) and for correct assignment to PEDS Paths (97% agreement). In terms of the 2012 accuracy findings, PEDS had a Sensitivity of 86% and Specificity of 74%. PEDS has been used in a variety of settings, including: Australia (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children); USA; Canada; the Middle East; Africa (Tanzania and South Africa); Asia (India, Indonesia, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand) ; the South Pacific; Europe (Iceland, Spain); and Great Britain. (Glascoe 2012).

Child Trauma Screening Questionnaire (CTSQ)3

This 10-item screening tool is a quick, cost-effective and valid self-report screening instrument for the detection of post-traumatic stress disorder (Kenardy JA et al. 2006). The CTSQ was validated in a study of 135 children (84 boys and 51 girls) aged between 6 years and 16 years old (mean age 10.8 years, SD 2.3 years) who were admitted to hospital after a variety of accidents, including car-related and bike-related accidents, falls, burns, dog attacks, and sporting injuries. The findings were compared with the results of the Children’s Impact of Events Scale and then validated against the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Child Version. This diagnostic tool has good test-retest reliability (κfrom 0.75 to 0.96) and moderate to high inter-rater reliability (κrom 059 to 0.92). (Kenardy et al. 2006)

The CTSQ correctly identified 82% of the children who demonstrated distressing post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms (9% of the sample). The CTSQ outperformed the Children’s Impact of Events Scale using a cut-off score of 17 (Kenardy 2006). Both screening tools were significantly better than chance in detection of children with post-traumatic stress disorder at 1 month (area under the curve 0.80, p<0.001 for CTSQ vs. 0.71, p<0.05) and the CTSQ was superior at 6 months (area under the curve 0.78 p<0.001) when compared with the Children’s Impact of Events Scale (area under the curve 0.64, p not significant).

The CTSQ demonstrated a Sensitivity of 0.85 at 1 month (95% confidence interval 0.65-1.04) and 0.82 at 6 months (95% confidence interval 0.59-1.05).

The CTSQ demonstrated a Specificity of 0.75 at 1 month (95% confidence interval 0.67-0.83) and 0.74 at 6 months (95% confidence interval 0.66-0.83)

The CTSQ is not a diagnostic test and many of the children identified as being at risk of post-traumatic stress disorder may not demonstrate sufficient features to warrant a clinical diagnosis when a diagnostic tool is used. However, the CTSQ is a valid tool to screen children at risk who would then warrant further investigation and management.

The study is limited by its low participation rate (48%) and the lack of data on non-participants. However, there are no better tools, with better published results and this tool has been recommended by numerous child psychiatrists and psychologists. The CTSQ is the standard mental health screening tool used in the Health Assessment for Refugee Kids (HARK) clinic in The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, which is part of the largest Children’s Hospitals Network in the Southern Hemisphere. HARK has been running continuously for over a decade and currently has over 400 consultations with refugee and asylum seeker children annually.

Professor Kenardy was informed that the CTSQ would be used as part of the screening tool by the paediatricians for the Australian Human Rights Commission visit to Darwin in October 2015. The CTSQ uses the term “the event” to prompt answers to questions (e.g., “Do you have bad dreams about the event?”). After discussion with a very experience Child Psychiatrist, in order to have consistency of reporting across the paediatric population screened, we decided to make the stay in the Nauru Regional Processing Centre “the event”. Thus, wherever “the event” was in the question, we replaced it with “Nauru” (e.g., “Do you have bad dreams about Nauru?”).

Hunter Opinions and Personal Expectations Scale (HOPES)4,5,6

This is a 12 item scale where children report whether the sentence describes them “extremely well”, “very well”, “moderately well”, “NOT very well” or “NOT at all” (underlines and capitals as per scale). Some of the questions are to assess hope and others are to assess despair. Two of the questions are the following:

- “ I generally believe that I will get what I want out of life” and

- “Even when things go right, I often fear that my future is NOT under my control”

These two questions are highly correlated with all the other questions on the hope and despair scales. These two questions are also correlated with anxiety and depression.

A recent review of tools to measure hope (Schrank et al. 2008) found 49 definitions of hope and 32 measurement tools. However, no single measure has been widely used in prospective research studies. Therefore, we decided to use one question on hope and one question on despair from the HOPES, the whole CTSQ and the whole Snyder Child Hope Scale.

Snyder Children’s Hope Scale (SCHS)7

This 6-item dispositional self-report index is used in children aged 8 years to 16 years. It shows internal consistency, is relatively stable over retesting and exhibits convergent, discriminant and incremental validity. The SCHS showed no gender differences, racial differences or age differences in the samples tested which enabled stratification by those characteristics (Snyder et al. 1997).

The SCHS provides a guide to the children’s expectational component (how they see their futures – with or without hopefulness), whereas the CTSQ screens for current post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology.

References

- Woolfenden S, Eapen V, Williams K, Hayen A, Spence N, Kemp L. A systematic review of the prevalence of parental concerns measured by the Parent’s Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS) indicating developmental risk. BMC Pediatrics 2014; 14: 231

- Glascoe F. Tools for Developmental-Behavioral Screening and Surveillance. Accessed 11th Oct 2015.

- Kenardy JA, Spence SH, Macleod AC. Screening for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Children After Accidental Injury. Pediatrics 2006; 118: 1002-1009.

- Nunn KP, Lewin TJ, Walton JM, Carr VJ. The construction and characteristics of an instrument to measure personal hopefulness. Psychological Medicine. 1996; 26(3): 531-545.

- Steed LS. A psychometric comparison of four measures of hope and optimism. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2002 (June); 62: 466-482.

- Schrank B, Stanghellini G, Slade M. Hope in psychiatry: a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2008; 118: 421-433

- Snyder CR, Hoza B, Pelham WE, Rapoff M, Ware L, Danovsky M, Highberger L, Rubinstein H, Stahl KJ. The Development and Validation of the Children’s Hope Scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 1997; 22(3): 399-421.

Appendix 2: Photos from visit to Wickham Point (Sand compound)

Fence at entrance to compound

Library

Play area

Bedroom

International Health Medical Service clinic

Play Room

Appendix 3. Illustrations from children in detention

Figure 1. “Me in the boat.” Girl 7years.

Figure 2. “Nauru. The Fence and locks.” Girl 7 years.

Figure 3. That is Nauru. All the people sad. We have in Nauru tents and we don’t have any houses. The fan is broken and it’s hot. We don’t do anything.” That is “me dead. I died. My dad is sad. My mum is sad – she has a baby in tummy. She is crying.” That’s “the fence with locks.”

Figure 4. “I jumped from the house to the ground and I died. My mum and dad are crying.” Girl 7 years.

Figure 5. “My dad, me and my mum behind the fence at Nauru.” Boy 6 years. This child wrote his boat number on the drawing.

Figure 6. Nauru. “Me crying My brother has a problem with his kidney and penis.” (His sibling awaits surgery).

Figure 7. “This is my life. Please help us.” Boy 9 years. This boy wrote his boat number on the drawing.

Appendix 4: Biographical notes of authors*

Elizabeth J Elliott AM

MD MPhil (Public Health) FRACP FRCPCH FRCP

Professor Elliott is a Distinguished Professor of Paediatrics and Child Health in the Sydney Medical School at the University of Sydney and a Consultant Paediatrician at the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network (Westmead). She holds a prestigious Senior Practitioner Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia and is currently a Chief Investigator on NHMRC grants worth over $15 million. She is involved in medical education and training; research; and policy development, including for the WHO. She advocates for women and kids through roles on the Boards of Cure Kids Australia, the Women’s College at the University of Sydney and the Hoc Mai Foundation; membership of the Steve Waugh Foundation Medical Advisory Committee, and as a Patron for the National Organisation for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD). Her work has a particular focus on disadvantaged children, including children with rare diseases, living in Immigration detention, in low-income countries in the Asia-Pacific, especially Vietnam; and Aboriginal children in remote communities. Elizabeth is Founder/Director of a national resource for facilitating the study of rare diseases, the Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit. She has a current research and national and international leadership role in the identification, management and prevention of FASD, including as Chair of the Australian Government’s National FASD Technical Network and Co-director of a Centre for Research Excellence in FASD. In 2015 she consulted to the Australian Human Rights Commission on the Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, appeared before the Inquiry and contributed to the Inquiry report The Forgotten Children. She visited Christmas Island and Wickham Point Detention Centre with the Commission and has interviewed over 150 asylum seeking children and their families. Elizabeth was selected for the Health Stream in the Prime Minister’s 2020 Summit in 2008, received the John Sands Medal from the Royal Australasian College of Physicians in xx, was named one of 100 Inaugural Women of Influence by Westpac and the Financial Review and was made a Member of the Order of Australia in 2008 for services to paediatrics.

Dr Hasantha Gunasekera

MBBS DCH MIPH (Hons) FRACP PhD

Dr Gunasekera is a General Paediatrician at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead (CHW) and a Senior Lecturer at The University of Sydney. He has worked at CHW for the last 2 decades, and in the CHW refugee clinic (Health Assessment for Refugee Kids, HARK) for the last decade. He provided specialist paediatric services in the Nauru Regional Processing Centre for International Health and Medical Services and donated all proceeds to HARK. He was on the organising committee for the International Paediatric Association conference in Melbourne in 2013. He is an Editor for the national paediatric journal (The Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health). He is the Coordinator for the Child and Adolescent Health Block of the Sydney Medical Program (responsible for the paediatric teaching for approximately 10% of Australia’s medical graduates every year). He has extensive research experience in disadvantaged communities, being an investigator on research with funding in excess of $13 million, and is part of the leadership group of Chief Investigators for a National Health and Medical Research Council Centre for Research Excellence (Indigenous Children’s Healthy Ears, #1078557).

*Professor Elliott and Dr Gunasekera conducted this work for the AHRC in a pro bono capacity.

[1] The Australian Human Rights Commission. The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into children in immigration detention 2014. https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/publications/forgotten-children-national-inquiry-children

[2] Elliott EJ. Report to the Australian Human Rights Commission Inquiry into the Impact of Immigration Detention on Children. Christmas Island Visit, July 14th to July 17th 2014. www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/ExpertReport/ChristmasIsland/2014.

[3] Corbett E, Gunasekera H, Isaacs D, Maycock A. Australia’s treatment of refugee and asylum seeker children: the views of Australian paediatricians. MJA 2014; 201 (7): 393-398.

[4] Paxton G et al. (Elliott E, Gunasekera H, Co-authors). ‘The forgotten children: National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention (2014). J Paediatr. Child Health 2015; 51: 365-8.

[5] Australian Government Department of Immigration and Border Protection and the Australian Border Force. Immigration Detention and Community Statistics Summary. www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/statistics/immigration-detention-statistics-30-Sept-2015.pdf

[6] Woolfenden S, Eapen V, Williams K, Hayen A, Spence N, Kemp L. A systematic review of the prevalence of parental concerns measured by the Parent’s Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS) indicating developmental risk. BMC Pediatrics 2014; 14: 231

[7] Kenardy JA, Spence SH, Macleod AC. Screening for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Children After Accidental Injury. Pediatrics 2006; 118: 1002-1009.

[8] Nunn KP, Lewin TJ, Walton JM, Carr VJ. The construction and characteristics of an instrument to measure personal hopefulness. Psychological Medicine. 1996; 26(3): 531-545.

4Snyder CR et al. The Development and Validation of the Children’s Hope Scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 1997; 22(3): 399-421.

[9] Woolfenden S, Eapen V, Williams K, Hayen A, Spence N, Kemp L. A systematic review of the prevalence of parental concerns measured by the Parent’s Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS) indicating developmental risk. BMC Pediatrics 2014; 14: 231

[10] The Australian Human Rights Commission. The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into children in immigration detention 2014. https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/publications/forgotten-children-national-inquiry-children

[11] Robjant K, Hassan R, Katona C. Mental health implications of detaining asylum seekers: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2009; 194: 306-12.

[12] Dudley M, Steel Z, Mares S, Newman L. Children and young people in immigration detention. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012; 25: 285-92.

[13] Kenardy JA, Spence SH, Macleod AC. Screening for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Children After Accidental Injury. Pediatrics 2006; 118: 1002-1009.

[14] Mares S, Jureidini J. Psychiatric assessment of children and families in immigration detention--clinical, administrative and ethical issues. Aust NZ J Public Health 2004; 28: 520-6.

[15] Robjant K, Hassan R, Katona C. Mental health implications of detaining asylum seekers: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2009; 194: 306-12.

[16] Dudley M, Steel Z, Mares S, Newman L. Children and young people in immigration detention. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012; 25: 285-92.

[17] Professor Elizabeth Elliott and Dr Hasantha Gunasekera Interviews with children and parents at Wickham Detention Centre, October 2015.

[18] Nunn KP, Lewin TJ, Walton JM, Carr VJ. The construction and characteristics of an instrument to measure personal hopefulness. Psychological Medicine. 1996; 26(3): 531-545.

[19] Steed LG. A psychometric comparison of four measures of hope and optimism. Educational and psychological measurement. 2002 (June); 62(3): 466-482.

[20] Schrank B, Stanghellini G, Slade M. Hope in psychiatry: a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2008; 118: 421-433

[21] Professor Elizabeth Elliott. Interviews at Wickham Detention Centre, October 2015

[22] Mares S, Jureidini J. Psychiatric assessment of children and families in immigration detention--clinical, administrative and ethical issues. Aust NZ J Public Health 2004; 28: 520-6.

[23] Robjant K, Hassan R, Katona C. Mental health implications of detaining asylum seekers: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2009; 194: 306-12.

[24] Dudley M, Steel Z, Mares S, Newman L. Children and young people in immigration detention. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012; 25: 285-92.

[25] Paxton G, Tosif S, Graham H, et al. Perspective: ‘The forgotten children: National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention (2014). J Paediatr Child Health 2015; 51: 365-8.

[26] Metherell L. Immigration detention psychiatrist Dr Peter Young says treatment of asylum seekers akin to torture. ABC News, 6th August 2014. Link: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-08-05/psychiatrist-says-treatment-of-asylum-seekers-akin-to-torture/5650992 (accessed 18th Sept 2015).

[27] Isaacs D. Nauru and detention of children. J Paediatr Child Health 2015; 51: 353-4.