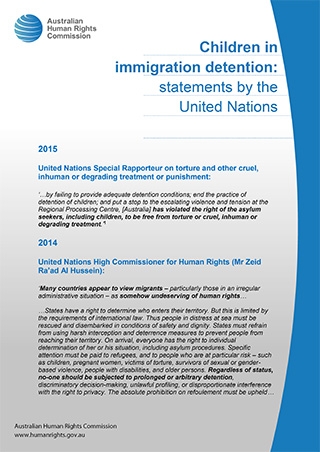

Children in immigration detention: statements by the United Nations

2015

United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment:

‘...by failing to provide adequate detention conditions; end the practice of detention of children; and put a stop to the escalating violence and tension at the Regional Processing Centre, [Australia] has violated the right of the asylum seekers, including children, to be free from torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.’[1]

2014

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (Mr Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein):

‘Many countries appear to view migrants – particularly those in an irregular administrative situation – as somehow undeserving of human rights...

...States have a right to determine who enters their territory. But this is limited by the requirements of international law. Thus people in distress at sea must be rescued and disembarked in conditions of safety and dignity. States must refrain from using harsh interception and deterrence measures to prevent people from reaching their territory. On arrival, everyone has the right to individual determination of her or his situation, including asylum procedures. Specific attention must be paid to refugees, and to people who are at particular risk – such as children, pregnant women, victims of torture, survivors of sexual or gender-based violence, people with disabilities, and older persons. Regardless of status, no-one should be subjected to prolonged or arbitrary detention, discriminatory decision-making, unlawful profiling, or disproportionate interference with the right to privacy. The absolute prohibition on refoulement must be upheld...

...Policies that seek to stamp out migration do not decrease the numbers of would-be migrants’.[2]

‘We continue to witness ill-treatment of migrants at borders; and receiving States increasingly subject migrants and asylum seekers to prolonged detention in deplorable conditions...the Committee has consistently applied the Convention to these situations, and has held that asylum seekers and undocumented migrants should never be detained – or, if at all, only as a measure of last resort.’[3]

‘...the detention of asylum seekers and migrants should only be applied as a last resort, in exceptional circumstances, for the shortest possible duration and according to procedural safeguards. Australia's policy of off-shore processing for asylum seekers arriving by sea, and its interception and turning back of vessels, is leading to a chain of human rights violations, including arbitrary detention and possible torture following return to home countries.’[4]

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees representative in Indonesia:

‘Children do not belong in detention and it is clear under international law that states should not detain them ...the negative impact that it has on a child's life at the very beginning of their life, to put them in this type of horrible situation, you can just imagine the negative consequences that it has on their psyche, on their wellbeing.’[5]

United Nations Committee against Torture:

‘[Australia should consider]...repealing...mandatory detention; ensuring that detention should be only applied as a last resort; establishing...statutory time limits for detention and access to an effective judicial remedy; review the necessity of the detention... It should also ensure that that...children and families with children are not detained or, if at all, only as a measure of last resort, after alternatives to detention have been duly examined and exhausted, when determined to be necessary and proportionate in each individual case, and for as short a period as possible...

The Committee is concerned at the State party’s policy of transferring asylum seekers to the regional processing centres located in Papua New Guinea (Manus Island) and Nauru for the processing of their claims, despite reports on the harsh conditions prevailing in these centres, including mandatory detention, including for children; overcrowding, inadequate health care; and even allegations of sexual abuse and ill-treatment. The combination of these harsh conditions, the protracted periods of closed detention and the uncertainty about the future reportedly creates serious physical and mental pain and suffering...

...[Australia] should guarantee that all asylum seekers or persons in need of international protection who are under its effective control are afforded the same standards of protection against violations of the Convention regardless of their mode and/or date of arrival.’[6]

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees:

‘Refugees are persons who are fleeing persecution or the life-threatening effects of armed conflict. They are entitled to better treatment than being shipped from one country to the next.’[7]

‘Nauru is not a place where adequate protection can be granted. This is quite obvious. We insist that this is the responsibility of the country that receives the people and that this should be an Australian responsibility.’[8]

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (Ms Navi Pillay):

‘I must emphasize that persons seeking international protection in the territorial sea or at maritime borders must be treated in the same way as those who apply for protection on land. Clearly much more needs to be done to protect the human rights of migrants in this region ... Recent violence in the Regional Processing Centre on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, has underscored the need to review the Regional Resettlement Arrangements signed by Australia with Papua New Guinea and Nauru, to ensure that the human rights of migrants and asylum seekers are fully protected in accordance with international law.’[9]

2013

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees:

‘...the harsh and unsuitable environment at the closed [Regional Processing Centre on Nauru] is particularly inappropriate for the care and support of child asylum-seekers. UNHCR is also concerned that children do not have access to adequate educational and recreational facilities. In light of the overall shortcomings in the arrangements, highlighted in this and earlier reports, UNHCR is of the view that no child, whether an unaccompanied child or within a family group, should be transferred from Australia to Nauru.’[10]

2012

United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child:

‘[Australia should] reconsider its policy of detaining children who are asylum-seeking, refugees and/or irregular migrants; and, ensure that if immigration detention is imposed, it is subject to time limits and judicial review.’[11]

[1] Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Addendum: Observations on communications transmitted to Governments and replies received, UN doc A/HRC/28/68/Add.1 (2015), para 19. At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session28/Pages/ListReports.aspx (viewed 14 May 2015).

[2] Statement by Mr Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (Speech delivered at UNHCR Dialogue on Protection Challenges, Theme: Protection at sea, 10 December 2014). At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=15399&LangID=E (viewed 14 May 2015).

[3] Opening address by Mr Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein High Commissioner for Human Rights at the Opening of the celebration of the 30th anniversary of the Convention against Torture, 4 November 2014. At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=15255&LangID=E (viewed 14 May 2015).

[4] Opening Statement by Mr Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein High Commissioner for Human Rights at the Human Rights Council 27th Session, 8 September 2014. At http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=14998&LangID=E (viewed 14 May 2015).

[5] G Roberts, ‘Asylum seekers: UNHCR urges Australia and other countries to stop detaining children’, ABC News, 28 November 2014. At http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-11-28/unhcr-wants-australia-to-stop-detaining-children/5924108 (viewed 14 May 2015).

[6] Committee against Torture, Concluding observations on the combined fourth and fifth periodic reports of Australia, UN doc CAT/C/AUS/CO/4-5 (2014), paras 16-17. http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CAT/C/AUS/CO/4-5&Lang=en (viewed 14 May 2015).

[7] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR statement on Australia-Cambodia agreement on refugee relocation (Press Release, 26 September 2014). At http://unhcr.org.au/unhcr/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=513:unhcr-statement-on-australia-cambodia-agreement-on-refugee-relocation&catid=35:news-a-media&Itemid=63 (viewed 14 May 2015).

[8] A Guterres in Refugee Council of Australia, Report on 2014 UNHCR Annual Consultations with NGOs (2014), p 5. At http://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/r/urpt/2014_UNHCR_NGO.pdf (viewed 14 May 2015).

[9] Opening Statement by Ms Navi Pillay United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, (Speech delivered at Human Rights Council 25th Session, 6 March 2014), p 6. At http://www.ishr.ch/sites/default/files/article/files/hcannualreport-statement.pdf (viewed 14 May 2015).

[10] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR monitoring visit to the Republic of Nauru: 7 to 9 October 2013 (2013), p 2. At http://www.refworld.org/docid/5294a6534.html (viewed 14 May 2015).

[11] Committee on the Rights of the Child, Concluding observations: Australia, UN doc CRC/C/AUS/CO/4 (2012), para 81. At http://www.ag.gov.au/RightsAndProtections/HumanRights/TreatyBodyReporting/Documents/UNCommitteeontheRightsoftheChild-Concludingobservations.PDF (viewed 14 May 2015).