2. Requirements for targeted recruitment strategies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to qualify as special measures (except in New South Wales)

The purpose of this section is to provide a nationally consistent set of requirements for a ‘special measure’ targeted recruitment strategy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The core elements of a special measure are essentially the same under all federal, state and territory discrimination laws. However, the wording of the criteria in the legislation of each jurisdiction differs slightly.[7]

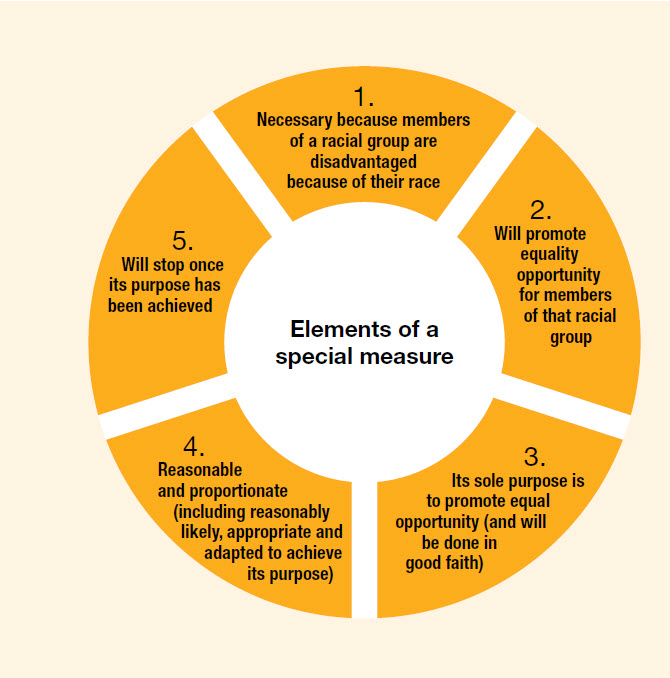

ELEMENTS OF A SPECIAL MEASURE

The set of requirements below represents a consolidation of the various requirements under the federal Racial Discrimination Act and state and territory discrimination laws. It reflects the strictest requirements across the jurisdictions, so that an employer who can demonstrate that their recruitment strategy meets all of these criteria can have confidence that they would meet the test in every jurisdiction. Employers can use the template provided in Appendix 1 of this guideline to record how their program meets these criteria.

Note that each requirement must be met, and that the requirements are interrelated and overlapping, and therefore should not be read in isolation.

2.1 Demonstrate that the targeted recruitment strategy is necessary because members of a racial group are disadvantaged because of their race

An action can only be considered a special measure and therefore consistent with discrimination law when that action is necessary for members of a disadvantaged racial group to enjoy their human rights equally with others.

To demonstrate that a special measure is necessary, an employer will need to provide recent and reliable data as evidence that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience disadvantage in employment because of their race.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) provides data which can be relied upon to demonstrate disadvantage and therefore that a special measure is necessary.[8] For example, in its 2011 Census of Population and Housing: Characteristics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, the ABS found that:

- about two in five Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 15 years and over were employed, compared with about three in five non-Indigenous people

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were about three times more likely than non-Indigenous people to be unemployed.[9]

The annual Closing the Gap reports released by the Prime Minister may also provide relevant data. For example, the Prime Minister’s 2015 report concludes that the gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians has widened in recent years. The proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 15-64 years who are employed fell from 53.8 per cent in 2008 to 47.5 per cent in 2012-13, while the proportion of non-Indigenous Australians who are employed increased from 75.0 per cent to 75.6 per cent.[10]

If an employer has data on the percentage of its workforce that is made up of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and/or the levels of employment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within the industry in which it operates, this would also be relevant.

Wherever possible, employers should consult with Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander communities in the areas in which they operate to ascertain whether targeted recruitment strategies are necessary. The Commission supports the view that ‘[p]referential programs should always, where remotely feasible, be developed in consultation with those being helped, and individuals should always be given the opportunity of receiving normal, non-preferential treatment should they so prefer.’[11]

Support of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities for a targeted recruitment strategy would assist an employer in demonstrating not only that the program is necessary, but also that the program meets requirements 2, 3 and 4 below. This support will generally lead to more effective implementation of the program.

A targeted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander recruitment strategy may also be included in the negotiation of an Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) with the local Aboriginal and /or Torres Strait Islander community. An example of an ILUA which includes agreement about employment outcomes is the Argyle Diamond Mine Participation Agreement, discussed in the box below.

Case study: The Argyle Diamond Mine Participation Agreement

The Argyle Diamond Mine Participation Agreement (the Argyle Agreement) is a registered Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) between Traditional Owners of the East Kimberley region of Western Australia, the Kimberley Land Council and Argyle Diamond Mine (Argyle Diamonds). The Argyle lease occupies the traditional country of the Mirriuwung and Gidja peoples as well the Malgnin and Woolah peoples.

In 2001, Argyle Diamonds and the traditional owners came to the table to renegotiate and renew the relationship between the traditional owners and the mining company. The ILUA negotiations were conducted by two committees, that of the traditional owners and of Argyle Diamonds.

A significant focus of the Argyle Agreement is to achieve training and employment outcomes for local Aboriginal people. Argyle Diamonds has made a commitment to give support and preference to local Aboriginal people for jobs and training at the mine. The Training and Employment Management Plan that is part of the Argyle Agreement includes business and employment principles that aim to achieve and maintain a 40 percent local Aboriginal employment quota on commencement of the underground mine in 2008, continuing until the mine closes.

2.2 Explain how the targeted recruitment strategy will promote equal opportunity for (and therefore provide a benefit to) members of a racial group

The special measure must be designed to improve the circumstances of a disadvantaged racial group by promoting equality of opportunity for that group. A targeted program aimed at increasing employment of a disadvantaged racial group is a clear example of a benefit which promotes equality of opportunity.

It is well-established in every jurisdiction that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples constitute racial groups (both separately and as a combined group).[12]

2.3 Show that the sole purpose of the targeted recruitment strategy is to promote equal opportunity for members of the disadvantaged group (and that it will be undertaken in good faith for that purpose)

A special measure should have as its sole purpose a specific and clear aim of addressing the situation where members of a racial group have experienced inequality.

The purpose of a special measure is determined by looking at the stated intention of the person undertaking the strategy, in this case, the employer.[13]

Accordingly, employers need to document their intention in conducting targeted recruitment strategies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, for example, by using the template attached at Appendix 1 of this guideline. That documentation should include reference to the evidence which demonstrates why the measure is necessary, as mentioned above. A detailed record of the planning and rationale behind the measure will serve both as evidence of its purpose, and of the good faith of the employer undertaking it.

The question of whether the sole purpose of the measure is to advance the rights of a disadvantaged group is closely related to the requirement for proportionality, discussed immediately below.

2.4 Show that the targeted recruitment strategy is generally reasonable and proportionate, including that it is reasonably likely, appropriate and adapted to achieve its purpose

A special measure must be designed to effectively address the actual disadvantage of the targeted group, that is, it must be ‘appropriate and adapted’ to its purpose.

An employer needs to show there is a rational connection between the planned strategy and its stated objective in such a way that it is reasonably likely that the strategy will be successful.

A special measure must also be proportional to the degree of disadvantage experienced by the target population.

All of these criteria are linked to the requirement to demonstrate by reference to evidence why the measure is necessary, that is, to identify the disadvantage suffered by the particular group. Once the particular disadvantage is identified, the measure must be designed to address that disadvantage.[14]

The principle of proportionality requires that the means adopted to address the disadvantage must not go beyond what is necessary to do so.

Case study: Reasonableness and proportionality

In The Ian Potter Museum of Art (Anti-Discrimination Exemption) [2011] VCAT 2236), the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal considered the proposal by the Ian Potter Museum of Art (part of the University of Melbourne) to recruit an Indigenous person in the role of an Assistant Curator. The Tribunal held that the proposal was proportionate and reasonably likely to achieve its purpose of increasing the representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on the staff of the Museum and the University. The Tribunal held that the proposal was reasonably likely to achieve its purpose because, upon an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person being employed in the position, this would increase the level of employment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the University. The Tribunal held that the proposal was also a proportionate measure as:

At present, out of a staff of 15, only one employee of the applicant is Indigenous. As at June 2009, across the University as a whole Indigenous employees represented less than 0.5% of the staff. That figure is dramatically less than the number required to represent the proportion of Indigenous people in the wider population. In these circumstances, the proposed conduct is a proportionate means of achieving the applicant’s purposes.

To demonstrate that a targeted recruitment strategy meets these requirements, an employer should refer back to the evidence of the disadvantage which needs to be addressed as mentioned above. An employer should then explain that the strategy is an appropriate way of increasing employment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. If an employer has unsuccessfully attempted to employ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the past without implementing a targeted program, this history would be relevant to include.

The test for proportionality will be the same whether the targeted recruitment strategy includes individual or bulk recruitment. Given the significant gap in employment outcomes between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians, a bulk recruitment strategy targeting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by an employer is unlikely to fail the test of proportionality.

2.5 Show that the targeted recruitment strategy will stop once its purpose has been achieved

A special measure must be temporary, and cannot permanently establish separate rights for a particular group. However, the appropriate duration of a special measure is determined by whether it has achieved its purpose, not by a predetermined passage of time.[15] A special measure can continue for an extended period, so long as it ends once its objective has been achieved. Therefore, it is recommended that an employer designing a targeted recruitment program build in periodic reviews to evaluate its effectiveness in achieving its purpose.

An employer may set targets for the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people intended to be employed as part of an Indigenous Employment Strategy or a particular recruitment program. The targeted recruitment program should end once those targets have been reached. However, a new program with different (higher) targets could then be undertaken.

Generally speaking, targeted recruitment strategies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples will no longer qualify as special measures once Indigenous Australians enjoy the same employment levels as non-Indigenous Australians.

Notes

[7] For the wording in a particular jurisdiction, see: Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth), s 8(1); Discrimination Act 1991 (ACT), s 27; Anti-Discrimination Act 1996 (NT), s 57; Anti-Discrimination Act 1991 (Qld), s 105; Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (SA), s 65; Anti-Discrimination Act 1998 (Tas), ss 25 and 26; Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic), s 12 (see also Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic), s 8(4)); Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (WA), s 51.

[8] See, for example, The Ian Potter Museum of Art (Anti-Discrimination Exemption) [2011] VCAT 2236, [25]-[26] and [39].

[9] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Census of Population and Housing: Characteristics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2011, ABS cat no 2076.0 (2012). At http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2076.0main+features802011 (viewed 2 June 2015

[10] Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australian Government, Closing the Gap: Prime Minister’s Report 2015 (2015) p 18, available at http://www.dpmc.gov.au/pmc-indigenous-affairs/publication/closing-gap-prime-ministers-report-2015#jobs (viewed 2 June 2015).

[11] G Evans, ‘Benign Discrimination and the Right to Equality’ (1974) 6 Federal Law Review 26, 30.

[12] See further the definitions of ‘race’ in Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth), sub-s 8(1) (and see International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, 1965, art 1(1) and (4)); Discrimination Act 1991 (ACT), Dictionary; Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW), s 4; Anti-Discrimination Act 1996 (NT), s 4; Anti-Discrimination Act 1991 (Qld), Dictionary; Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (SA), s 5; Anti-Discrimination Act 1998 (Tas), s 3; Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic), s 4; Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (WA), s 4.

[13] ‘Any fact which shows what the persons who took or who promoted the taking of a measure intended it to achieve casts light upon the purpose for which it was taken provided the measure is not patently incapable of achieving what was so intended’: Gerhardy v Brown (1985) 159 CLR 70, 135 (Brennan J).

[14] In Gerhardy v Brown Brennan J stated ‘The need must match the purpose’: 159 CLR 70, 137.

[15] See for example Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, General Recommendation 25, on article 4, paragraph 1, of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, on temporary special measures, (2004), para 20. At: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/recommendations/General%20recommendation%2025%20(English).pdf (viewed 18 June 2015).

Long Text Description

The Chart "Elements of a special measure" is a pie chart in the shape of a wheel. It has this information:

1) Necessary because members of a racial group are disadvantaged because of their race.

2) Will promote equal opportunity for members of that racial group.

3) Its sole purpose is to promote equal opportunity (and be done in good faith).

4) Reasonable and proportionate (including reasonably likely, appropriate and adapted to achieve its purpose).

5. Will stop once its purpose has been achieved.