Information about children in immigration detention

Last updated 6 January 2016

Under Australia’s system of mandatory immigration detention, all non-citizens who are in Australia without a valid visa must be detained. This includes children.

The vast majority of children who are in immigration detention are children who arrived in Australia by boat, seeking asylum. Some of them came with family members, but some of them came alone.

There have been significant improvements over recent years, including the transfer of many children into community – based alternatives to closed detention. However, the Commission continues to have serious concerns about the impact of Australia’s mandatory immigration detention system on children, and Australia's compliance with its obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child. These concerns were most recently confirmed during the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014.

How many children are in immigration detention in Australia, and where they are detained

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection publishes statistics setting out the number of people, including children, in immigration detention. As at 30 November 2015 there were:

- 174 children in closed immigration detention facilities: 104 are held in closed immigration detention facilities in Australia and 70 children are detained in the Regional Processing Centre in Nauru

- 331 children in community detention in Australia.

The vast majority of the children who are in closed detention in Australia are held in low security immigration detention facilities. As at 30 November 2015 there were:

- 65 children detained in Wickham Point Alternative Place of Detention (which was originally classified as a high security Immigration Detention Centre but in 2013 was re-designated as an APOD for holding families with children)

- 3 children detained in Perth Immigration Residential Housing

- 11 children detained in Sydney Immigration Residential Housing

- 8 children detained in Brisbane Immigration Transit Accommodation

- 17 children detained in Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation.

Children are detained in the Regional Processing Centre in Nauru because of Australia’s system of transferring asylum seekers (including children) who come by boat to third countries. For more information about Australia’s system of third country processing, including the Commission’s (and others) concerns about the health and welfare of child asylum seekers in Nauru, click here.

Unaccompanied children who arrive in Australia

Asylum seeker children who arrive in Australia alone without a parent or guardian are subject to mandatory detention the same way accompanied children are.

Australia has obligations in relation to children who arrive in Australia unaccompanied, especially those who are seeking asylum, to ensure that they receive special protection and assistance. Australia has an obligation under the Convention on the Rights of the Child to ‘ensure alternative care’ for these children.

An important element of the care of unaccompanied children is effective guardianship. In the absence of their parents, the legal guardian of an unaccompanied child has the ‘primary responsibility for the upbringing and development of the child’, and is under an obligation under the CRC to act in the best interests of the child. Under Australian law, the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection is the legal guardian of ‘non-citizen’ unaccompanied children.

The Commission has a range of concerns relating to unaccompanied children in immigration detention. Most significantly, the Commission is concerned that the Minister’s role as guardian of unaccompanied children creates a conflict of interest, as the Minister is also responsible for administering the immigration detention regime under the Migration Act and for making decisions about granting visas and transferring children to Nauru. Given these multiples roles, it is difficult for the Minister, or his delegate, to make the best interests of the child the primary consideration when making decisions concerning unaccompanied children.

The Commission has repeatedly recommended that an independent guardian be appointed for all unaccompanied children in immigration detention, to ensure that their rights are protected.

For more information about unaccompanied children in detention, see Chapter 10 of The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014.

What international law says about the detention of children

Australia ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) in 1990. One of the basic principles of the CRC is that the best interests of the child should be a primary consideration in all decisions that affect them.

The CRC sets out specific requirements to protect the liberty of children, including the requirements that:

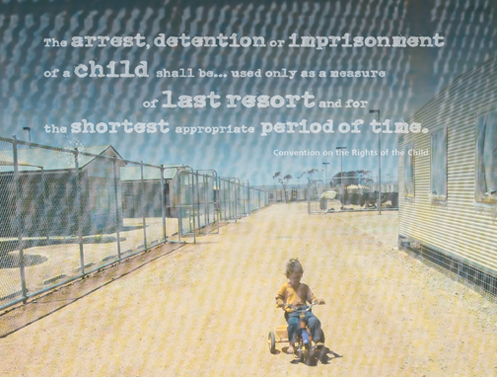

- children must only be detained as a measure of last resort

- children must only be detained for the shortest appropriate period of time

- children should not be detained unlawfully or arbitrarily

- children in detention have the right to challenge the legality of their detention before a court or another independent body.

The CRC also provides that:

- children seeking asylum have a right to appropriate protection and assistance - because they are an especially vulnerable group of children

- children separated from their parents have a right to special assistance

- children in detention should be treated with respect and humanity and they have the right to healthy development and to be able to recover from past trauma

- children seeking asylum, like all children, have rights to physical and mental health; education; culture, language and religion; rest and play; protection from violence; and to remain with their parents.

The Commission’s work in relation to children in immigration detention

The Commission works in a number of ways to promote and protect the human rights of all asylum seekers, refugees, and people in immigration detention, including children. However, because children are vulnerable and are given special protection under international human rights law, the Commission has maintained a particular focus on the rights of children in its immigration detention work.

The Commission has previously conducted three national inquiries relating to children in immigration detention in Australia. The reports of these inquiries make recommendations to the Australian Government aimed at protecting the human rights of children. For further information see:

- A last resort? National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention (2004)

- An age of uncertainty - Inquiry into the treatment of individuals suspected of people smuggling offences who say that they are children (July 2012)

- The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention 2014 (2015)

A last resort? The report of the first National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention

Prior to 2005, hundreds of children and their family members were detained in remote immigration detention centres, some for months or years. Most of these children had arrived by boat and were seeking asylum in Australia.

The Commission was gravely concerned about the human rights of these children. In 2004, the Commission released A last resort? the report of the National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention. The Inquiry found that Australia’s mandatory immigration detention system was fundamentally inconsistent with Australia’s obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Under the CRC, a child should only be detained as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.

The Inquiry also found that children who are detained for long periods are at high risk of serious mental harm, and that long-term detention significantly undermines a child’s ability to enjoy a range of human rights, including the right to education and the right to enjoy the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

Following the completion of the 2004 National Inquiry, there were two positive developments in Australia’s laws and practices regarding holding children in immigration detention.

Firstly, the Federal Parliament amended the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) in 2005 to affirm ‘as a principle’ that a minor should only be detained as a measure of last resort.

Secondly, the Australian Government gradually removed children from Australia's high security immigration detention centres, and moved significant numbers of unaccompanied children and families with children into community detention.

The Forgotten Children: the report of the second National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention

In the years following A last resort? the Commission continued monitoring the situation of children in detention through visiting detention facilities, investigating complaints and providing public reports (to see the Commission’s work from 2010-2014, click here) The Commission’s ongoing work throughout the period demonstrated that serious concerns about the detention of children remained.

In mid 2013, the numbers of children in closed immigration detention began reaching unprecedented levels in Australia’s history (over 1,600 on 30 April 2013, and reaching 1,992 in July 2013). The Commission planned an investigation into what had changed in terms of the situation for children in detention in the 10 years since A last resort?

The National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention was launched on 3 February 2014. It investigated the laws, policies and practices of successive Australian Governments during the period from January 2013 to October 2014. The purpose of the Inquiry was to investigate the ways in which life in immigration detention was affecting the health, well-being and development of children, 10 years on from the Commission’s last inquiry.

The overarching finding of the Inquiry was that the prolonged, mandatory detention of asylum seeker children causes them significant mental and physical illness and developmental delays, in breach of Australia’s international obligations.

The Commission found that the mandatory and prolonged immigration detention of children is in clear violation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, including:

- Art 3(1), which requires that in all actions concerning children, the best interests of the child should be a primary consideration

- Art 24(1) which provides that all children have the right to the highest attainable standard of health

- Art 37(b), which requires that children should only be detained as a measure of last resort, and for the shortest appropriate period of time.

To read the full report of the 2014 Inquiry The Forgotten Children, click here. For a summary of the report, including its recommendations, see the summary factsheet on the Inquiry available here.

Following the launch of the Inquiry, the Government has released hundreds of children and their family members from immigration detention facilities. As at 31 January 2014, there were 1,006 children in detention in Australia, and 132 in detention in Nauru. By 30 June 2015 there were 127 children in detention in Australia, and 88 detained in Nauru.

The majority of these children and their family members who have been released have been granted bridging visas and permitted to live in the community. The Commission welcomes the use of bridging visas as a more humane and effective approach to the treatment of asylum seekers than holding them in detention facilities for long and indefinite periods of time.