Access for all: Improving accessibility for consumers with disability

Introduction

This resource provides practical tips for businesses on improving access to goods, services, facilities, premises and information for consumers with disability.

Following these tips will not only reduce the likelihood of discrimination complaints against your business, but will also increase your access to the market, and benefit the community, through greater economic participation of people with disability.

Over 4 million people in Australia experience disability.[1] That’s around 1 in 5 Australians. People with disability, as well as their friends, relations and colleagues, constitute a significant group of consumers. However, businesses can often unintentionally overlook the needs of these consumers, making it difficult for them to access goods and services. These businesses may be missing out on a significant customer base, as well as potentially breaching anti-discrimination laws.

The Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) (DDA) makes it against the law to discriminate against a person because of disability when providing goods, services or facilities, or access to public premises.

In 2014–15, the Australian Human Rights Commission received 323 complaints about disability discrimination in the provision of goods, services and facilities. A number of these complaints also raised issues about access to premises.

There are state and territory anti-discrimination laws which also prohibit disability discrimination.[2] These laws provide for people to make complaints to state and territory anti-discrimination authorities. The wording of each Act is slightly different, so to work out your obligations it is important that you check the DDA and the legislation in each state or territory in which your business operates. You can also contact the Australian Human Rights Commission and state and territory anti-discrimination authorities for information about what is covered under the law.[3]

What does the Disability Discrimination Act say?

The DDA says that disability discrimination occurs when a person is treated less favourably, or not given the same opportunities as others in a similar situation, because of their disability. The disability could be temporary or permanent; a physical, intellectual, sensory, neurological, learning or psychosocial disability; a disease or illness; physical disfigurement; or medical condition or work-related injury.

The DDA also protects people with disability who may be discriminated against because they are accompanied by an assistant, interpreter or reader; or a trained animal such as a guide, hearing or assistance dog; or because they use equipment or an aid, such as a wheelchair or a hearing aid.

The DDA makes it against the law to discriminate against a person because of their disability either:

- by refusing to provide them with goods or services or make facilities available; or

- because of the terms or conditions on which, or the manner in which, the goods, services or facilities are provided.[4]

The DDA also makes it against the law to discriminate against someone because of their association with a person with disability.

Discrimination can be direct, meaning a person with disability is treated less favourably than a person without that disability in the same or similar circumstances. An example of possible direct disability discrimination is where a person is refused entry to a restaurant because they are blind and have a guide dog.

Discrimination can also be indirect. Indirect disability discrimination can happen when conditions or requirements are put in place that appear to treat everyone the same, but actually disadvantage some people because of their disability. For example, it may be indirect discrimination if the only way to enter a shop is by a set of stairs, because people with disability who use wheelchairs would be unable to enter the building. The law says however that it will not be unlawful discrimination where the person imposing the requirement or condition can demonstrate that it is reasonable in the circumstances.[5]

The DDA requires businesses to make reasonable adjustments to enable a person with disability to access goods, services or facilities.[6] However, the DDA says it will not be against the law to discriminate in providing access to goods, services or facilities if it can be demonstrated that making the required adjustments would cause ‘unjustifiable hardship’. [7]

Before claiming that adjustments will create unjustifiable hardship, it is recommended that businesses:

- thoroughly consider how an adjustment might be made

- estimate the cost of making the adjustment and whether any financial or other assistance is available

- consider the potential benefit or detriment of the adjustment for

- any specific person concerned

- the business

- the community

- discuss this directly with any person involved

- consult relevant sources of advice.

Making information accessible

One area in which businesses may unintentionally engage in discrimination is in the manner and/or format in which they provide important information to consumers, and require information from consumers.

Examples of issues raised in complaints:[8]

Unable to access bills:

A woman who is blind complained that a utility company did not provide bills in an accessible format. She was seeking access to online billing as a private and convenient method of payment. The complaint was resolved with an agreement that the business would provide a document in Braille setting out the range of payment options; continue a pilot project to provide summary bills in Braille; and make electronic text format bills available within a specified time period.

Unable to access product assistance:

A woman with a hearing impairment complained that when she sought help from an information technology company in relation to a recently purchased product, she was told that assistance was only available over the phone. The company said that the complainant had received incorrect advice and the company did provide online product assistance and assistance via TTY relay services. The company apologised for what had happened and offered the complainant 12 months free access to a service upgrade.

Limited identification requirements:

A 27-year-old woman with an intellectual disability complained that she was refused entry to a hotel because she could not produce a driver licence to prove she was over 18 years of age. The complaint was resolved with the hotel agreeing to accept a copy of the woman's birth certificate as proof of identify and lobby in support of a generally available and acceptable ‘proof of age’ card.

A woman who is blind complained that she had been discriminated against when a credit provider refused to accept her Blind Citizens Australia identity card in place of a driver licence and required her to obtain legal advice as she could not read the printed contract herself. The complaint was resolved when the respondent agreed to accept the identity card, permit contracts to be read to a vision impaired person by an independent person rather than just a lawyer, and investigate how contracts could be produced in accessible formats.

Tips for making information accessible

It is important not to make assumptions about how people can receive or communicate information. The best approach is to make important information available to consumers in a variety of formats.

To ensure that key information is accessible to as many people with disability as possible:

- Make important information available to consumers in multiple formats, not just in hard copy written format. Options could include information being conveyed:

- orally by staff (in person, or over the phone, including, in the case of people who are Deaf or have a hearing impairment, through use of the Telephone Typewriter (TTY) National Relay Service)

- in hard copy written material (including a large 18 font size print option)

- electronic formats including by email, via websites and online chat services

- on computer disc

- as an audio recording.

Businesses could also consider installing an audio loop in their public shopfronts or offices to assist people with hearing aids, and providing an Auslan interpreter or Braille option on request.

What is the National Relay Service?

The National Relay Service (NRS) is a phone service for people who are Deaf, have a hearing impairment or have complex communication needs. The NRS relay officer provides a link for the parties to the call and relays exactly what is said or typed. The NRS relay officer is present for the duration of the call to ensure smooth communication between the parties but does not change or interfere with what the parties say.

If a business provides information or services to customers by telephone, customers with disability are entitled to use the NRS to access the business’s telephone service.

For more information on the NRS, visit their website; www.relayservice.com.au

- Provide written information in clear and concise language that is easy to understand, in a font size no smaller than 12pt.

- Provide a variety of methods for consumers to contact the business, for example in person, over the phone (including by use of a TTY), or by email.

- When a consumer is required to produce a form of identification, for example when entering into a contract or seeking entrance to an age-limited premises, accept multiple forms of identification. Do not only rely on a driver licence, as a person with a disability may not have one.

- Allow for accessible payment options e.g. allow for credit card payments to be signed instead of the person having to enter and remember a PIN.

- Ensure staff are trained about how to provide information in a non-discriminatory way, and to communicate effectively and respectfully with people with disability (see more in the last section of this resource).

Find out more

See the Information Checklist published by the Disability Services Commission of Western Australia. [9]

Making premises accessible

The DDA makes it against the law to discriminate against people with disability in relation to access and use of public premises.[10] This applies to places such as shops, cafes, restaurants, banks, cinemas, theatres and sporting venues. Public ‘premises’ can also include an aircraft or vehicle, a place (whether enclosed or built on or not); and a part of premises, for example, customer bathrooms.[11]

There are national legally-binding standards which set out technical requirements for those building or upgrading premises to ensure people with disability can access and use buildings, as required by the DDA.[12] The Commission has published a guideline on the application of these standards to assist people to implement them.[13]

In relation to existing premises, there are a number of things that can be done to ensure access for people with disabilities. Often inadequate or inappropriate management, maintenance and housekeeping practices can make otherwise accessible premises inaccessible – for example, keeping accessible toilets locked or using them for storage.

Examples of issues raised in complaints

Barriers at entrances and items in aisles:

A woman who uses a wheelchair complained that she had difficulty shopping in her local supermarket due to such things as turnstiles at the entrance and displays and goods being placed in the aisles. The complaint was resolved when the supermarket agreed, among other things, to remove turnstiles at the entrance convey instructions to staff about keeping passages clear and remodel displays to ensure aisles are kept clear.

Accessible checkout lanes frequently being closed:

A man who uses a wheelchair complained about difficulties at his local supermarket including that the accessible checkout lanes are frequently closed. The complaint was resolved when the supermarket agreed to ensure that at least one accessible lane will always be open.

Locked accessible toilets:

A woman who uses a wheelchair complained that she could not use the accessible toilets in a shopping centre because they were always locked, while other toilets were not. The complaint was resolved when the shopping centre agreed to unlock the accessible toilet facilities during opening hours and upgrade the doors to make access easier and to comply with relevant Australian Standards.

Tips for maintaining accessible premises

- Do not lock accessible bathrooms or lifts while premises are in use by members of the public. Ensure accessible bathrooms can be reached via a continuous accessible path of travel.

- Do not use accessible bathrooms or change rooms as storage areas.

- Avoid constructing temporary displays or stacking goods in a manner which obstructs aisles. Make sure there are continuous accessible paths of travel around and within premises.

- Make sure that counter heights, lift buttons, EFTPOS facilities, door handles, etc. are within reach of a person using a wheelchair.

- Ensure that lift buttons have raised tactile and Braille information next to them and that the lifts provide audible information telling passengers what floor they have arrived at.

- Maintain adequate lighting levels throughout premises.

- Provide adequate signage for people with disability accessing or using the premises.

- Do not allow surfaces to become dangerously worn or slippery.

- Provide designated parking spaces for people with disabilities and maintain a continuous accessible path of travel from the parking space to the premises.

Access to transport

The DDA makes it against the law to discriminate against people with disability in relation to access to or use of public aircraft, vehicles or vessels.[14] This includes airlines, taxis, buses, trains, trams, rental cars, ferries and cruise ships.

There are legally binding technical requirements for public transport providers to ensure access for people with disability to transport.[15] The Commission has published a guideline on the requirements for accessible bus stops.[16]

Many disability discrimination complaints made to the Commission are about people with disabilities being denied travel in taxis or on airplanes.

Examples of issues raised in complaints:

Difficulty travelling with an assistance animal:

A man who is blind and has a guide dog complained that when he called to book a taxi and informed the operator that he was travelling with a guide dog, he was told not to count on a taxi turning up. The complaint was resolved when the taxi company agreed, among other things, to develop a disability access program; engage the local Guide Dog Association to provide awareness training for drivers; and pay the complainant $200 compensation.

Lack of ramps for buses:

A man who uses a wheelchair complained that ramps on the accessible buses in his area were frequently out of order for long periods. The complaint was resolved when the bus operator confirmed that the ramps had been repaired and arrangements made to ensure the workshop gave priority attention to ramp maintenance and repairs in the future

Restrictions on independent travel

A woman complained that when her sister, who is 50 years old and has an intellectual disability, arrived to book in for her flight, she was told that she could not travel unaccompanied, The complainant said her sister has a high level of capacity including holding licences to operate various machines. The complaint was resolved when the airline apologised, advised that it had reviewed is staff information and training, compensated the complainant’s sister for the embarrassment she experienced and agreed that in future she was able to travel unaccompanied.

Tips for improving access to transport

- Be aware that under the DDA, it is against the law to refuse a person access to transport because of disability, unless you can establish:

- if the refusal is because of a requirement or condition which the person with disability is unable to comply with, that requirement or condition is reasonable in the circumstances, or

- it would cause unjustifiable hardship for you to make the adjustments necessary to provide access.

This includes refusing a person access to transport because they are accompanied by an assistance animal. More information about the DDA and assistance animals is provided in the following section.

- Ensure information relevant to passengers with disability is provided on the transport service’s website. Such information may include specific booking processes, requirements for passengers with disability, location of accessible bus/train stops, timing of accessible services, access features, etc.

- Make sure booking forms and mobile apps are accessible to people with disability.

- Provide training to frontline staff on the delivery of accessible transport to passengers with disability

- Take steps to inform booking agents (e.g. travel agents) of relevant considerations for passengers with disability (e.g. need to demonstrate fitness to travel, disability equipment carriage restrictions, access features, etc.)

Access to premises and services for people who use assistance animals

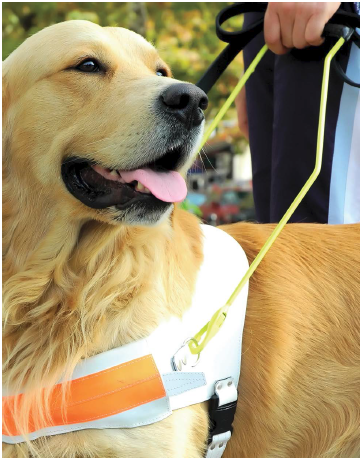

The DDA makes it against the law to discriminate against a person with disability who is accompanied by an animal that is trained to alleviate the effects of their disability.[17] In 2014–15 complaints to the Commission about discrimination because the person had an assistance animal increased by 44%.[18]

The most common and well-known example of assistance animals are guide dogs who assist people who are blind or have a vision impairment. However, the category of assistance animals recognised by the DDA is much broader than just guide dogs. Assistance animals can also be trained to assist people who are Deaf or have a hearing impairment, people who require physical support for mobility, people with psychosocial disability and people who have medical conditions such as epilepsy.

If you are not sure whether an animal is an assistance animal it is not against the law to ask a person with disability to provide evidence that an animal is an assistance animal or that it is trained to meet standards of hygiene and behaviour appropriate for an animal in a public place.[19] Evidence can include identification from a state or territory assistance animal register, a card from a registered training organisation or a medical certificate.

The DDA also says it is not unlawful to request or require that an assistance animal remain under the control of the person. An animal does not need to be on a harness or leash to be under a person’s control.[20] For example, a person with disability may control an assistance animal through eye contact, voice commands, touch or close physical proximity.

It may also not be unlawful to discriminate against a person with disability accompanied by an assistance animal if you reasonably suspect the animal has an infectious disease and the discrimination is reasonably necessary to protect public health or the health of other animals.[21]

Examples of issues raised in complaints

Unable to access a restaurant:

A man who is blind and uses a guide dog complained that when he and his family went to a restaurant to order take-away food he was asked to leave because of his dog. The restaurant manager said he was not aware that guide dogs were allowed in restaurants. He apologised for what happened, agreed to arrange training about guide dog access for his staff and place a “Guide Dog Welcome” sticker at the front of the restaurant.

Refused access to a sports club:

The complainant has a disability that affects her mobility and balance and uses an assistance dog to alleviate the effects of her disability. She was a regular spectator at a local sports club and claimed the manager refused her access to the club because of her assistance animal. The club said that the complainant's assistance animal did not meet that state's legislative requirements for accreditation and explained it was unaware that under the DDA an 'assistance animal' includes an animal that is trained but not necessarily accredited under state law. The complaint was resolved when the club agreed to review its policies regarding assistance animals to ensure compliance with federal disability discrimination law. The manager also expressed regret for any misunderstanding that had occurred.

Refused access to an aircraft

In the recent case of Mulligan v Virgin Australia Airlines[22] the Federal Court of Australia found that Virgin Australia had breached the DDA when it refused to allow Mr Mulligan, a man with cerebral palsy, vision impairment and mobility impairment, to be accompanied by his dog in the cabin during a domestic flight. Mr Mulligan’s dog had been trained by a dog training school to assist Mr Mulligan with his disability.

The Court ordered Virgin to pay Mr Mulligan $10,000 in compensation.

The Court said that it is not necessary for an assistant animal to be trained by an accredited organisation, as long as it has been trained by a person or organisation to assist a person with disability to alleviate the effect of the disability, and to meet standards of hygiene and behaviour that are appropriate for an animal in a public place.

Tips for improving accessibility for people with assistance animals

- Be aware that under the DDA, it is against the law to refuse a person access to premises, facilities, goods or services simply because they are accompanied by an assistance animal, unless you can establish

- if the refusal is because of a requirement or condition which the person with the assistance animal is unable to comply with, that requirement or condition is reasonable in the circumstances, or

- it would cause unjustifiable hardship for you to make the adjustments necessary to provide the person access with their assistance animal.

- Be aware that a guide dog is only one form of assistance animal and there are other assistance animals such as those that assist people with hearing disabilities and medical conditions.

- If you are unsure if an animal is an assistance animal, the law says that it is OK to ask the person with the disability to provide some evidence that the animal is an assistance animal and has been trained to meet standards of hygiene and behaviour appropriate for an animal in a public place.

- If you are unsure whether an animal is an assistance animal, ask the person before asking them to leave the premises or leave their animal outside.

- Provide frontline staff with information and/or training about assistance animals.

- Find out if your state or territory has a register for assistance animals. This may help you or your staff clarify if an animal is an assistance animal. However, be aware that not all assistance animals may be registered (e.g. animals still in training or from other states or territories).

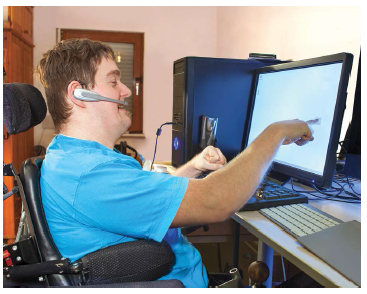

Access for people using mobility devices

As well as protecting the rights of people who have assistance animals, the DDA also prohibits discrimination against people who use a ‘disability aid’.[23] A disability aid is defined as any equipment that is used by a person with disability which assists to lessen the effect of the disability.[24] Examples of disability aids include mobility devices such as wheelchairs and mobility scooters. [25]

Under the DDA, it may be against the law for the owner or manager of a shop, restaurant, club, or other venue to refuse entry to someone who uses a scooter if it is being used as a disability aid. It may also be against the law to restrict the access of the person only to certain parts of the premises.

Businesses should consider the needs of consumers who use scooters as a mobility aid.

The general tips for maintaining accessible premises, mentioned in the earlier section of this resource, also apply to people who use mobility devices.

Find out more

For more information about how to ensure premises are accessible for people with disability using mobility scooters, see the Commission’s Advisory Note on Mobility Scooters in Registered Clubs. [26]

Access online

Available data indicates that the majority of people with disability who are 15 years or older use online services to do things such as purchase goods, pay bills and conduct banking.[27] There are different technologies which can assist people with disability to access and use online resources. For example, people with vision impairments can use screen-reader software which reads out what is on the computer screen.

Making information available online in addition to providing it in hard copy, over the phone, or in person can be an important way of making sure that people with disability can access that information. Similarly, making goods and services available via accessible websites or mobile apps can enable usage by people with disability who would otherwise not be able to access them.

The requirement in the DDA that providers of goods and services not discriminate against a person because of disability applies to online services as it does in the physical world. Online providers of information, goods and/or services need to consider the accessibility of their websites and mobile device applications for people with disability.[28]

Detailed guidance on how to design accessible websites is contained in the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (Web Guidelines) developed by the World Wide Web Consortium.[29] The Commission has developed an Advisory Note on accessibility of web resources to clarify the requirements of the DDA in this area, and explain how compliance with them can be best achieved, with reference to the Web Guidelines.[30]

The World Wide Web Consortium has also developed a document explaining how the Web Guidelines can be applied to mobile web content and mobile web apps.[31]

Examples of issues raised in complaints

Problems with online banking:

A woman who has a vision impairment complained that she could not access her credit union’s online banking service because the security features that had been installed to verify identify were not accessible to her. The complaint was resolved when the credit union agreed to upgrade its site to provide an accessible method for verifying a person’s identity.

Problems with online shopping:

A woman with a vision impairment complained that her supermarket had upgraded its website and in doing so had made it difficult for her to arrange a time for delivery. The complaint was resolved with an agreement that the company would make further improvements to enhance the accessibility of its online shopping service.

Tips for increasing accessibility of online content

- Be aware that material that is presented only in an image-based format such as GIF or TIF will not be accessible to some people with disability.

- Use plain fonts that are easy to read. Avoid fonts that are decorative or stylised.

- Make sure there is enough contrast between foreground text and background colours so that the text is easy to read.

- Do not provide content only in pdf format, as screen-readers generally cannot read these properly. If you include pdfs, provide the same information in Word and/or html format.

- Make sure you include text descriptions for all non-text content, including all images and graphs, for example, using the Alt text function.

- Avoid scanned pictures of text e.g. a photo of a menu and text boxes, as screen-readers can’t read these

- Provide captions and/or transcript for multimedia (i.e. audio and video) content.

- Do not set audio or video content to play automatically when a page is loaded, as this can interfere with the use of screen-readers.

- Rather than using a ‘CAPTCHA’ to protect against malicious machine interference with your website (for example wavy letters in an image file which a user must identify and retype), use an accessible alternative such as requiring the user to reply to an email sent to their email address.

- Make sure that all the content on your website can be navigated by keys on the keyboard (i.e. it does not require use of a mouse).

- Make technical support available for consumers who need assistance using your website, via online chat session, phone or email

- Test the accessibility of your website, and where necessary speak to an accessibility professional.

Find out more

For more information, resources and assistance in relation to web accessibility...

- visit the Media Access Australia website

- visit the Access IQ website

- visit the Vision Australia website

Planning accessible events

Those who plan events, including meetings, festivals, conferences, lectures, and fundraisers, need to take all reasonable steps to ensure that the event is accessible so that people with disability can attend and participate. Consideration should be given to the issues raised in each of the earlier sections of this resource, including:

- whether information about the event is provided in (multiple) accessible formats when promoting and inviting people to the event

- whether any website used for promotion or ticketing for the event is accessible

- whether the chosen venue, and the set up within the venue, is accessible for people with disability, including for people using mobility devices or assistance animals.

Examples of issues raised in complaints

Lack of audio loop:

A man who has a hearing impairment said he attended a lecture series at a public venue but was unable to hear the content as the theatre did not have an audio loop. The complaint was resolved on the basis of an agreement to provide the man with an apology, refund the fee he had paid and install an audio hearing loop in the theatre.

Lack of lift access:

A man who uses a wheelchair complained that a publicly funded arts facility did not have public lift access. This meant that patrons who could not use stairs had to use the goods lift and be accompanied by staff through otherwise ‘off limit’ areas of the building. The complaint was resolved with an agreement that the arts centre would install an appropriate public lift.

Tips for making events accessible

Below are some simple tips to increase the accessibility of your event:[32]

- Explain the accessibility of the venue on the invitation or registration form and request attendees to inform you of any accessibility requirements they have. For example:

Access for people with disability

The venue is accessible for people using wheelchairs. All handout materials will be available in accessible electronic format on request. If you have any other accessibility requirements in order to participate fully, please let us know, and the event organiser will contact you.

- Make sure there is sufficient clear, simple and visible signage to direct people where to go.

- Ensure the venue is large enough and set out in such a way that people with disability, including people using mobility devices such as wheelchairs or scooters, can move freely around even when the venue is full.

- When setting up seating arrangements and allocations, allow people with disability a choice of seating, including options with a clear view of the stage/speakers platform. This is particularly important for people who are Deaf or have a hearing impairment.

- Ensure that any speakers are aware that if they are using powerpoint slides or videos in their presentations, they need to provide the same information in a format which is accessible for people who have vision or hearing impairments. For example, speakers could provide an oral description of powerpoint slides, provide hard copy, electronic and/or audio copies of the material ahead of the event, and/or use captioning or Auslan interpreters during the presentation.

- Brief venue and registration staff about their responsibility to avoid discriminating against people with disability, and about any access issues, such as allowing people using assistance animals into the venue, location of accessible toilets and availability of handouts in accessible formats. This information could be provided to staff before the event in writing, or in a briefing session.

- Give a specified staff member responsibility for addressing any accessibility issues that arise on the day of the event, and make sure that all staff working at the event are aware of who that person is.

Communicating effectively with people with disability

The key to resolving any accessibility issues is respectful and effective communication with consumers with disability, and the provision of practical assistance in response to their requests. Training your staff on how to communicate with people with disability is an important step in ensuring you are providing an accessible service.

The following are some key tips for communicating with people with disability:[33]

- Talk directly to the person with disability, not the other people who may be with them (such as a sign language interpreter).

- Ask the person first if they want assistance, and if they answer yes, ask how you can best assist them. Do not assume they need assistance, or that you know what they require.

- If a person is Deaf or has a hearing impairment:

- make sure you face the person when you speak

- move out of areas with lots of background noise

- have a pen and paper to help you communicate, if necessary.

- If a person has a vision impairment or is blind:

- identify yourself by name to them

- if appropriate, ask for their name so you can address them directly and they know you are talking to them

- if the person asks for assistance to go somewhere, ask which side they would prefer that you stand and offer your arm so they can hold onto it.

- Do not pat, talk to, or otherwise distract a guide dog or other assistance animal.

- Use appropriate language – For example use the term ‘person with disability’ rather than ‘disabled person’. When describing facilities for people with disability, use the word ‘accessible’ (e.g. ‘accessible toilet’, ‘accessible parking’, ‘accessible entry’).

Further information

Australian Human Rights

Commission

Level 3, 175 Pitt Street

SYDNEY NSW 2000

GPO Box 5218

SYDNEY NSW 2001

Telephone: (02) 9284 9600

National Information Service: 1300 656 419

TTY: 1800 620 241

Email: infoservice@humanrights.gov.au

Website: www.humanrights.gov.au/employers

These documents provide general information only on the subject matter covered. It is not intended, nor should it be relied on, as a substitute for legal or other professional advice. If required, it is recommended that the reader obtain independent legal advice. The information contained in these documents may be amended from time to time.

Revised June 2016.

[1] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2012 ABS cat no 4430.0 (2013) (viewed 16 December 2015).

[2] See Discrimination Act 1991 (ACT); Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW); Anti-Discrimination Act 1996 (NT); Anti-Discrimination Act 1991 (Qld); Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (SA); Anti-Discrimination Act 1998 (Tas); Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic); Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (WA).

[3] See the Australian Human Rights Commission’s National Information Service at the Australian Human Rights Complaints information page

[4] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) s 24.

[5] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth), s 6.

[6] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) sub-ss 5(2) and 6(2).

[7] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) ss 4 (see definition of ‘reasonable adjustment’); 5(2), 6(2) and 11.

[8] Complaints brought to the Commission are resolved on the basis of ‘no admission of legal liability’. It should also be noted that a respondent to a complaint may not necessarily agree with the factual situation as set out by the complainant, but will agree to participate in conciliation to try to resolve the complaint.

[9] Disability Services Commission Western Australia, Access and Inclusion Resource Kit: Information Checklist (2014) (viewed on 23 February 2016).

[10] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) s 23.

[11] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth), s 4.

[12] See Disability (Access to Premises – Buildings) Standards 2010 (Cth). The Premises Standards cover matters such as the design and construction of ramps and stairways, accessible toilets, and hearing augmentation systems. The current Premises Standards are available at the Federal Register of Legislation webpage, but note that these Standards are currently under review, so may be revised after the date of this publication.

[13] See Australian Human Rights Commission, /node/814 (Version 2) (2013) (viewed 23 February 2016).

[14] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) s 23 (and see definition of premises in s 4).

[15] See the Disability Standards for Accessible Public Transport 2002 (Cth). Available at the Federal Register of Legislation webpage (viewed 23 February 2016).

[16] Australian Human Rights Commission, Guideline for promoting compliance of bus stops with the Disability Standards for Accessible Public Transport 2002 (2010) (viewed 23 February 2016).

[17] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth), s 8.

[18] See Australian Human Rights Commission, Assistance Animals and the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) (18 January 2016) Australian Human Rights Commission (viewed 16 March 2016).

[19] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) sub-s 54A(5) and (6).

[20] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) sub-s 54A(2) and (3).

[21] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) sub-s 54A(4).

[22] [2015] FCAFC 130.

[23] See Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth), s 8.

[24] Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth), sub-s 9(3).

[25] Scooters are increasingly being used by people of all ages as a mobility aid: see Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, Mobility scooter usage and safety survey report (2012) (viewed 23 December 2015).

[26] Australian Human Rights Commission, see Advisory Note on Mobility Scooters in Registered Clubs (2014) (viewed 23 February 2016).

[27] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2012 ABS cat no 4430.0 (2013), Table 22 Persons Aged 15 Years or Over, Living in Households, Computer and internet access and use, by age and disability status - 2012 (viewed 4 January 2016).

[28] In terms of what is a reasonable level of accessibility under the DDA, see the discussion of ‘unjustifiable hardship’ in the earlier section of this resource ‘What does the Disability Discrimination Act say?’

[29] The Web Guidelines and related resources are available at this page on the W3 website (viewed 4 January 2016). The Web Guidelines represent the most comprehensive and authoritative international benchmark for best practice in the design of accessible websites. The Commission recommends that businesses aim for an ‘AA’ level of compliance with the Web Guidelines: see ‘How to Meet WCAG 2.0: A customizable quick reference to Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 requirements (success criteria) and techniques’, at this page on the W3 website (viewed 27 January 2016).

[30] Australian Human Rights Commission, World Wide Web Access: Disability Discrimination Act Advisory Notes ver 4.0 (2014) (viewed 23 February 2016).

[31] W3C, Mobile Accessibility: How WCAG 2.0 and Other W3C/WAI Guidelines Apply to Mobile (2015) (viewed 23 February 2016).

[32] These tips are based on the Accessible Events Guide developed by the Meetings and Events Industry of Australia in partnership with the Commission: see Meetings and Events Australia, Accessible Events: A guide for Meeting and Event Organisers ).

[33] These tips are based on the Accessible Events Guide developed by the Meetings and Events Industry of Australia in partnership with the Commission: see Meetings and Events Australia, Accessible Events: A guide for Meeting and Event Organisers ).