Implementing the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture : Options for Australia

2008

Implementing the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture : Options for Australia

A report to the Australian Human Rights Commission by Professors Richard Harding and Neil Morgan (Centre for Law and Public Policy, The University of Western Australia)

Download in Word Format [429KB]

Download in PDF Format [217KB]

Table of contents

- Background, summary and recommendations

- Introduction

- Scope and priority setting

- Primary and secondary places of detention and existing monitoring arrangements

- OPCAT requirements and criteriaa

- Developing an OPCAT-compliant NPM in Australia

- Implementation

- Recommendations

1 Background, summary and recommendations

Background

1.1 The Australian Human Rights Commission commissioned Professors Richard Harding and Neil Morgan from the Centre for Law and Public Policy, Law School, University of Western Australia to complete research in to the implementation in Australia the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT). The terms of reference for the research were as follows:

-

Identify, to the maximum extent possible, all of the places of detention in Australia that could come within the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT) definition of ‘places of detention’ (based upon categories provided by the Commission).

-

(a) Describe the existing Australian bodies whose function is to monitor places of detention, the scope of their powers and the standards against which they conduct monitoring.

(b) Consider whether there are places of detention in Australia that are currently not monitored at all by an external monitoring body.

(c) Analyse whether existing monitoring bodies meet the requirements of the NPM. -

Conduct a comparative study of how the NPM operates in other federal states.

- Consider what model of NPM may be the most appropriate to Australia.

This research was completed in October 2008.

Summary

1.2 By ratifying OPCAT Australia will commit itself to establishing National Preventive Mechanism(s) (NPMs) to prevent torture and other forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment falling short of torture.

1.3 The NPM arrangements must cover all ‘places of detention’ within all parts of Australia as well as relevant offshore locations such as military and immigration detention facilities.

1.4 The range of such places includes well-recognised areas of State detention of citizens, such as prisons, juvenile detention institutions, police stations, locked psychiatric wards and immigration detention centres. We recommend that these are the highest priority areas. However, OPCAT is much wider in scope and also extends to prisoner transport, court security, military detention facilities and aged care hostels where residents are detained involuntarily. Inspection systems must therefore also cover these facilities.

1.5 The nature of the NPM role will revolve around visits-based inspections by an agency possessing functional independence.

1.6 At present there are very few agencies within Australia that carry out functions within the OPCAT remit in an OPCAT-compliant way. This means that the creation of an OPCAT-compliant system will require ground up review and not just a ‘tweaking’ of existing arrangements. However, in some areas (including prisons, juvenile detention facilities, psychiatric wards, immigration detention centres, military detention facilities, any places of detention operated by national intelligence services and old people’s homes) there are a number of agencies across Australia whose statutory responsibilities and operational capacity could be bolstered to meet OPCAT criteria. These agencies are often of relatively recent development. The area that appears to have consistently lagged behind is police lock-ups and police stations.

1.7 The obligation of the Commonwealth Government will be to ensure that the provisions of OPCAT extend to all parts of the States and Territories comprising Australia without any limitations or exceptions, so that the visits-based NPM system is supported and sustained throughout Australia.

1.8 The Commonwealth Parliament possesses constitutional authority under the external affairs power to enact legislation to achieve its international obligations pursuant to ratification.

1.9 The NPM arrangements are related to and underpinned by the role of the United Nations Subcommittee for the Prevention of Torture (SPT), and the Commonwealth’s obligation upon ratification includes ensuring that the SPT is enabled to carry out its designated role.

1.10 NPM models could be unitary or mixed, and variants of these models have been adopted both in other federal States and in unitary States.

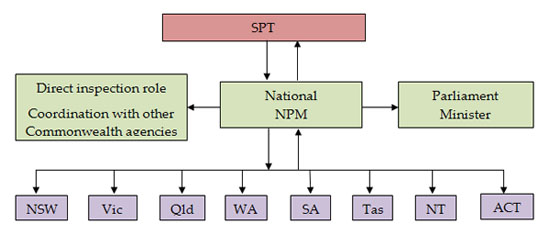

1.11 The preferable approach for Australia will be to adopt a ‘mixed model’ whereby the Commonwealth creates and empowers a national coordinating NPM and the States and Territories create subsidiary NPMs to cover places of detention within their own jurisdictional authority.

1.12 This should preferably be achieved by way of Commonwealth and State/Territory complementary legislation, rather than by direct Commonwealth legislation imposed upon the States and Territories.

1.13 The criteria and standards that each of the NPM agencies should meet are described in paragraph 6.1 of this Report. They include functional independence; clear statutory authority; proper resourcing for regular visits and other work; free and unfettered access to places of detention, documentation and detainees; the ability to make recommendations; and the authority to promulgate standards.

1.14 The role of the national coordinating NPM should be as follows:

- To oversee and direct an immediate stock-take of all places of detention within Australia;

- To exercise quality control over the activities of the State and Territory NPMs;

- To carry out sample inspections of places of detention within the jurisdiction of State and Territory NPMs;

- To carry out inspections of places of detention falling within its direct jurisdiction; and

- To deal with the SPT on all matters of OPCAT compliance and liaison for Australia.

1.15 OPCAT functions in relation to all places of detention within the control of all Australian police forces should preferably be exercised by the national coordinating NPM.

1.16 OPCAT provides that an existing agency may be designated as the NPM as long as it meets, or is amended to meet, the required criteria. This Report recommends that the national coordinating NPM should be a suitably adapted existing agency rather than a new agency.

1.17 Of the agencies that currently exist, both the Commonwealth Ombudsman and the Australian Human Rights Commission (the Commission) meet OPCAT standards of functional independence and have experience of carrying out activities closely related to the OPCAT remit.

1.18 Taking account of the Commission’s links into Australia’s international human rights obligations and of international practice relating to OPCAT, the Commission appears to be the more appropriate body to undertake the national coordinating NPM role.

1.19 If the Commission does become the national coordinating NPM, it would need to be appropriately resourced to build its capacity for OPCAT inspection and monitoring roles. A new Commissioner position should be created to take specific responsibility for all OPCAT functions.

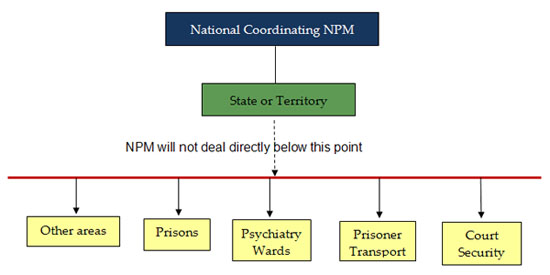

1.20 Whilst the States and Territories should work out their own NPM arrangements, there would be some advantage in their establishing or designating a single body as the relevant NPM and in any event no more than one such agency per jurisdiction should have a direct relationship with the national coordinating NPM.

1.21 International experience suggests that the consultation process with the States and Territories that has already commenced should be broadened so as to receive input from ‘civil society’ such as peak groups, NGO’s and human rights organisations within Australia.

1.22 There is a risk that momentum will be lost if the parties become sidetracked by fine details. A strict time limit should therefore be imposed on the consultation process, after which the Commonwealth should either ratify unreservedly (if practical implementation seems reasonably attainable within 12 months of that date) or should ratify subject to a Declaration under OPCAT Article 24.

1.23 In developing the NPM model for itself and offering guidance to the States and Territories, the Commonwealth should note that the Inspector of Custodial Services Act 2003 (WA) provides a strong template.

Recommendations

Our findings and analysis lead to the following recommendations.

Recommendation 1: Stock-take

The ‘stock-take’ of existing ‘places of detention’ and inspection agencies that we have commenced should be continued and finalised at Government levels as a priority.

Recommendation 2: Mixed Model

Australia should adopt a ‘mixed’ model for its NPM in which responsibility is shared between the States, the Territories and the Commonwealth, but there must be (i) a national coordinating NPM and (ii) a single coordinating agency within each State and Territory.

Recommendation 3: The national coordinating NPM

Rather than establishing a new agency as the national coordinating NPM, the Australian Human Rights Commission should be designated as the national coordinating NPM.

The HREOC Act and the internal organisational arrangements should be reviewed to ascertain whether additional statutory powers are required and to establish an OPCAT commissionership.

Resource needs should be scoped and provision made for providing them.[1]

Recommendation Four: Legislative Basis of OPCAT

A comprehensive Commonwealth statute should be enacted to enshrine OPCAT and to set out the processes through which it will be implemented across Australia.

Complementary State and Territory legislation should follow.

Recommendation Five: Police Places of Detention

Reflecting the increasing coordination between Australian police eservices, the need for consistency in the development of standards, and for resourcing reasons, responsibility for OPCAT-compliance in the context of police stations and lock-ups should be vested in the national coordinating NPM.

Recommendation Six: Model NPM Legislation

The legislation governing the Western Australian Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services should be used as a template for the powers of the State, Territory and national NPMs.

Recommendation Seven: Consultation and Implementation

In addition to consultations with governments and government agencies, the process of OPCAT consultations should include the non-government sector.

An implementation timetable should be established. The following timetable should be achievable:

- 2009: consultations should be completed.

- First quarter of 2010: principles governing Australia’s NPM system to be finalised.

- Second quarter of 2010: OPCAT to be ratified according to the following considerations:

- If practical implementation within 12 months is feasible, ratification should be unreserved.

- If a longer implementation period (maximum 3 years) is necessary, OPCAT should be ratified subject to a Declaration under Article 24.

2 Introduction

2.1 Shortly after being elected to office in late November 2007, the incoming federal Labor government announced its intention that Australia should become a signatory to the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other forms of Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT). This will be a very significant step in the history of the protection of human rights in Australia. Furthermore, the rights that will be protected through OPCAT should also form part of any national domestic Human Rights Act should such legislation be enacted at a future date.[2]

2.2 In effect, OPCAT brings to operational life the United Nations Convention against Torture and other forms of Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT). UNCAT sought to give meaning to some fundamental statements of principle contained in general United Nations instruments. These include Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, both of which provide that no one may be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

2.3 By way of shorthand, UNCAT is usually described simply as the ‘Convention against Torture’. Article 1 of UNCAT defines torture as follows:

... any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.

2.4 However, it is crucial to recognise that UNCAT and OPCAT extend well beyond ‘torture’ thus defined. Article 16(1) of UNCAT is particularly important:

Each State Party shall undertake to prevent in any territory under its jurisdiction other acts of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment which do not amount to torture as defined in article 1, when such acts are committed by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. (Authors’ emphasis)

At their broadest, therefore, UNCAT and OPCAT extend to any form of degrading treatment which occurs with the acquiescence of the state.

2.5 Under Article 16, the main UNCAT protections that apply with regard to ‘torture’ are made equally applicable to those forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment that do not amount to ‘torture’. This means, inter alia, that under the terms of Article 11 every State Party must:

... keep under systematic review interrogation rules, instructions, methods and practices as well as arrangements for the custody and treatment of persons subjected to any form of arrest, detention or imprisonment in any territory under its jurisdiction, with a view to preventing [such treatment or punishment].

2.6 Since UNCAT and OPCAT require the monitoring and prevention of all forms of cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment, they extend to a wide range of detention situations.[3] One key aspect of this Report is to attempt to identify the main places of detention that will be covered in Australia. This is not as easy as might be supposed and will no doubt be a matter of ongoing discussion and clarification within and between all Australian jurisdictions, at Commonwealth, State and Territory levels.

2.7 To pick up on our earlier language, OPCAT makes UNCAT ‘operational’ in two main respects. First, there is an international dimension: Australia must allow the United Nations Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture (or SPT) to visit any place of detention and must ensure free and unfettered access.[4] Secondly, there is a domestic / national dimension: Australia must establish a National Preventive Mechanism (or NPM). The NPM will have powers that mirror those that apply to the SPT and will play a dual role: it will be both the national point of contact for the SPT and a monitoring and accountability agency in its own right. For reasons that will emerge, and without downplaying the importance of the SPT, we believe that the NPM will, for most practical purposes, be the linchpin of the Australian system.

2.8 OPCAT takes account of the constraints and difficulties that States Parties may encounter in setting up a single, all-encompassing NPM by providing that multiple bodies may be constituted as NPMs. If OPCAT is to be effective, there needs to be some flexibility in the NPM model. Accordingly, Article 3 states:

Each State Party shall set up, designate or maintain at the domestic level one or several visiting bodies for the prevention of torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

This provision is of particular importance for federal States, such as Australia, in the light of Article 29 which states:

The provisions of the present Protocol shall extend to all parts of federal States without any limitations or exceptions.

However, as will be seen, the right of States Parties to establish multiple NPMs is also relevant to the capacity of unitary States, such as New Zealand, to establish NPM arrangements that are workable within their domestic governance structures.

3 Scope and priority setting

3.1 The principal forms of detention in Australia, in terms of their frequency, duration and intensity, are as follows:

- imprisonment of adults;

- detention in a secure institution for juveniles;

- detention in a police lock-up or police station;

- involuntary detention in a closed psychiatric institution; and

- detention in an immigration detention centre.

3.2 These are the ‘big five’ not only for Australian purposes but also for practical purposes under OPCAT, so we will term them the primary categories or places of detention.[5] They cover the main categories of criminal, civil and administrative detention.[6]

3.3 However, there are numerous other situations where the State exercises its power to detain citizens. These may be for other purposes, or for shorter periods, or as a concomitant of one of the main categories of detention, or in a manner that is sui generis. These situations include the following:

- detention facilities under military jurisdiction;

- court custody centres / holding cells;

- transport vehicles for prisoners or juvenile detainees or arrestees or any other person journeying to or from a place of detention;

- places where persons are held under applicable laws against terrorism before being transferred to prison jurisdiction;

- transit zones and health quarantine areas at international airports;

- facilities where people are detained by national intelligence services ;

- secure welfare hostels relating to wards of the State; and

- aged care homes and hostels where restrictions are placed on the movement of residents for their own safety.

3.4 These can be said to be secondary categories or places of detention. That is not to say that they are less important in principle than those we have called the primary places of detention. Nor is it to suggest that the international legal obligations upon Australia after OPCAT ratification will be any less compelling. The distinction is made simply as a matter of analytical convenience in a context where the day-to-day administration of NPMs will inevitably require that some prioritisation will have to be made as to the allocation of time and resources.[7] Past experience and observation tell us that cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment can and does occur in such places. We also recognise that as Australia moves to OPCAT implementation, there is room for further debate as to whether some of these secondary categories (such as military detention facilities) should be moved into the primary category in terms of prioritisation. However, quantitatively the occasions for improper conduct tend to be fewer, the time-frames are more transient, and the structural opportunities are more circumscribed in the case of these secondary categories.

3.5 OPCAT has not yet been subject to authoritative interpretation. The scope of UNCAT’s sister treaty – the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment – has in practice been focused on the primary places of detention identified in paragraph 3.1, above.[8] However, the following provisions of OPCAT show that the Protocol is wide enough to cover any involuntary detention situation that occurs pursuant to State authority, wherever it occurs and however brief its duration.

3.6 Article 1 refers without reservation to ‘places where people are deprived of their liberty’. Article 4(1) more explicitly provides that:

Each State Party shall allow visits ... to any place under its jurisdiction where persons are or may be deprived of their liberty, either by virtue of an order given by a public authority or at its instigation or with its consent or acquiescence (hereinafter referred to as ‘places of detention’).

All the situations set out in paragraphs 3.1 and 3.3 would appear to fall within this definition and thus to be ‘places of detention’ for the purposes of OPCAT.

3.7 Article 4(2) seems to put the matter beyond doubt:

For the purposes of the present Protocol, deprivation of liberty means any form of detention or imprisonment or the placement of a person in any form of public or private custodial setting from which this person is not permitted to leave at will by order of any judicial, administrative or other authority.

The clear intention of OPCAT, given its application to any form of degrading treatment, is to give a wide meaning to the notion of detention.

3.8 This means that the United Nations Subcommittee for the Prevention of Torture (the SPT) would be empowered to inspect all such places once Australia ratifies OPCAT. As a matter of common sense, however, the SPT, if it carried out a routine inspection in Australia, would be likely to concentrate its energies on a sample inspection of some or all of the primary categories or places of detention. Although the SPT is in its relatively early days, this appears to be the pattern of its activities to date.[9] But the SPT (like its European counterpart, the Committee for the Prevention of Torture or CPT) is able to conduct ‘targeted’ as well as sample inspections. It might well choose to do this in the event that a particular incident or series of incidents in a secondary place (or places) of detention was to trigger its attention.[10]

3.9 Although the international processes for monitoring and inspection are important to the structure and effectiveness of OPCAT, we firmly believe that the main practical significance of its implementation will lie in the National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) that Australia will be obliged to establish. SPT inspections will be quite rare, and in practice it is the NPM that will regularly inspect places of detention and that will act as a source of information to the SPT. The NPM is also Australia’s buffer against potential international criticism.[11]

3.10 The NPM is not only an inspection agency: it also offers some very positive potential benefits. It will be in the position to develop standards which will meet international and national expectations, and which can drive improved accountability and performance nationally and locally. Improved performance and benchmarking are also likely to result in better value for money in terms of service delivery. It is therefore critical that Australia’s NPM processes are firmly grounded in law, adequately resourced in practice, and made fully ‘OPCAT-compliant’.

3.11 The format of Australia’s NPM is a matter for full discussion later. However, even at this early point in the analysis it is apparent that NPM arrangements could collapse under the weight of their own jurisdictional reach if they were designed in such a way as to reach as frequently and as readily into the secondary categories or places of detention as into the primary categories or places of detention. In implementing OPCAT, therefore, the Commonwealth Government should be wary of design overkill.

3.12 Of course, it would not be lawful or proper to attempt to exclude secondary categories or places of detention from NPM jurisdiction, once established. Nor is it suggested that the Commonwealth Government would desire to legislate in such a way. However, it is inevitable that, whatever NPM arrangements are ultimately made, the responsible agency or agencies will need to prioritise their activities, and the natural way of doing so will be to concentrate the available resources mostly on primary categories or places of detention.

4 Primary and secondary places of detention and existing monitoring arrangements

4.1 As part of this project we have written a separate paper entitled Places of Detention & OPCAT-Style Inspection Systems in Australia: Working Paper & Source Material (the Working Paper). This charts the situation in each Australian State and Territory with respect to three of their major places of detention, namely, prisons, juvenile detention centre and locked psychiatric wards. It also contains information regarding the Commonwealth’s jurisdiction with respect to immigration detention centres, military detention centres and nursing homes. For reasons that will be discussed later,[12] the Working Paper does not include details of police detention facilities, despite the fact that they are an OPCAT priority.

4.2 Working by jurisdiction, the Working Paper seeks to identify the main places of detention and the responsible government department. Then it aims, where possible, to match existing monitoring arrangements against key OPCAT expectations. We will draw on that work as relevant, in the body of this Report. It is important to describe our methodology and to make some observations about what the Working Paper revealed, some of its limitations, and the reasons why it remains a ‘work in progress’.[13] It is also critical to recognise that although additional work needs to be done to finalise an inventory of Australian places of detention, this does not in any way detract from our central arguments: if there were well-resourced OPCAT compliant bodies already operating, we would have found them.

4.3 The first point is that it is by no means easy to identify all ‘places of detention’. This is partly because of OPCAT’s breadth and depth. Our research methodology was to peruse relevant legislation and regulations as well as searching, where possible, the websites of the agencies responsible for places of detention in our primary and secondary categories. Over and above that, we conducted general internet searches. We further tested this methodology against the jurisdictions with which we are most familiar before applying it to other jurisdictions.

4.4 Even with the primary and most obvious place of detention, adult prisons, we encountered unexpected difficulties. For example, one official source of information about one of the Australian jurisdictions indicated that it had three more prisons than another official source had indicated. Differences of this sort can be accounted for. It may be, for example, that one set of figures on ‘prisons’ includes ‘work camp’ facilities and the other excludes them. On this point, there can be no doubt that work camps will be covered by OPCAT (they may be ‘open’ but prisoners are certainly not ‘free to leave’). The numbers will also fluctuate if new prisons come on line or if old prisons are temporarily closed for refurbishment. However, this example serves to illustrate an important point: there must be a formal national stock-take or inventory of places of detention. The national coordinating NPM should be charged with the responsibility of first overseeing this ‘stock-take’ and then of adding or removing places from the inventory of detention as necessary.

4.5 One of the most critical areas in terms of the stock-take will be police lock-ups and police stations. It proved impossible, using our methodology, to pin down the situation in any jurisdiction. We recommend that, as part of ongoing OPCAT consultations between the Commonwealth and the States and Territories, each police service should produce an inventory of its facilities at police stations as well as designated ‘lock-ups’. In terms of the Australian Federal Police and Customs, it is our understanding that they have their own interview rooms but that they use State and Territory lock-ups if the person is to be detained. Here, again, current practices need to be clarified in order to understand the full ramifications of OPCAT implementation.

4.6 There are also significant methodological problems in attempting to describe with certainty the current inspection and accountability mechanisms. Our primary sources were legislation, regulations, websites of the agencies responsible for running the places of detention, websites of accountability agencies, and our own working knowledge. Again, we tested this methodology against the jurisdictions with which we are most familiar before applying it elsewhere. Even so, it is possible that we have not quite captured all of the external monitoring processes that are currently in place. However, it should be noted that if we were unable to find an agency through such processes, the agency in question is too low-profile: accountability, visibility and accessibility go hand in hand.

4.7 It is likely that some of the agencies who will be subject to OPCAT will suggest that we have not placed sufficient weight on the internal accountability mechanisms that operate within most government departments. These mechanisms apply to all of the relevant departments’ operations, but tend to have particular resonance where OPCAT-subject services (such as prisons, prisoner transport and court security services) have been contracted out. Here, it is likely that the department in question will establish contract management teams, complementing the general professional standards groups that have typically been created for internal monitoring of departmental activities. There is no doubt that, when properly funded and run, these mechanisms can be of considerable value. However, contract management systems and internal professional standards mechanisms do not meet OPCAT criteria. In any event, they are not a substitute for effective external processes. For example, compliance with the letter of a contractual obligation or some other performance measure may simply not come to grips with the subtleties of what is meant by ‘degrading’ treatment.

4.8 This Report, along with our allied Working Paper, clearly indicates the extensive scope and quantity of detention situations found in the nine Australian jurisdictions. In contemplating workable NPM arrangements, it is useful to identify the legal typology of such situations in terms of the ‘public authority’ (to adopt the terminology of Article 4.1 of OPCAT[14]) that instigates or consents or acquiesces to that detention.

4.9 Legally, there are three main typologies:

- Categories or places of detention in the States or the Territories that derive their authority to detain people exclusively from the relevant legislation of the particular State or Territory. Examples are: prisons; juvenile detention centres; police lock-ups; court custody centres/holding cells; closed psychiatric wards; custodial transport vehicles; and secure welfare hostels for children.

- Categories or places of detention, wherever physically located, that derive their authority to detain people exclusively from Commonwealth law. Examples are: immigration detention centres[15]; detention centres under military jurisdiction, including such places in overseas locations;[16] police cells/lock-ups administered by the Australian Federal Police (AFP); transit zones and health quarantine areas at international airports; and any facilities operated by national intelligence services.

- Categories or places of detention where there are overlapping or intersecting Commonwealth and State/Territory legislative arrangements. These include: detention of alleged terrorists; prisoners convicted under Commonwealth criminal law; and persons held at aged care hostels.

4.10 The importance of this analysis is that, in seeking to conceptualise new NPM arrangements, it is desirable to explore as a first option whether it is possible to work within these typologies rather than against them or across them. Put another way, can the energy of existing governance and administrative mechanisms be harnessed and recast so as to meet OPCAT standards for NPM arrangements? If primary responsibility for a category or place of detention rests, in both a day-to-day and a legislative sense, with a particular ‘public authority’ or sovereign government, it is good organisational theory and practice also to reside the accountability in that entity. That philosophy is clearly consonant with the provision in Article 3 of OPCAT that there may be multiple NPM bodies within a State Party.

4.11 Some aspects of the accountability mechanisms set out in this Report and the Working Paper will probably be subject to further elaboration and clarification during the national consultations on OPCAT. However, what our work does reveal, very starkly, is that current accountability arrangements for most categories or places of detention in Australia fall well short of OPCAT standards. There are, in fact, very few OPCAT-compliant mechanisms in existence in any of the nine Australian jurisdictions.

4.12 The detailed OPCAT requirements and the development of an OPCAT compliant model for Australia are the subject of discussion in the next two sections of this Report. At this point, it is sufficient to note that very few of the existing mechanisms are fully autonomous from the operational department nor are their reporting lines independent. There are some notable exceptions to this, and these may well provide models for the development of NPM arrangements. But the main picture is one of extensive shortfall from OPCAT requirements. This means that the creation of adequate NPM arrangements will not simply be a question of tweaking existing accountability mechanisms.

5 OPCAT requirements and criteria

5.1 OPCAT is constructed in such a way as to set out, first, the requirements on States Parties to facilitate the direct activities of the SPT (the international dimension) and, second, the requirements for establishing and facilitating an NPM structure (the national or domestic dimension).

5.2 The international dimension is relatively straightforward and the necessary implementation provisions will be spelled out later. As previously noted, direct inspections by the SPT will be quite infrequent. In its First Annual Report, the SPT estimated that with its existing resources it could take as long as five years to cover the existing States Parties (34 at that time) on a single occasion.[17] The SPT therefore considered that its contact with the NPM mechanism would be no less important than its direct inspection capacity and role. This view is in practical terms clearly correct. In considering the question of the implementation of OPCAT, as we have said, it seems clear that the domestic NPM arrangements rather than the direct international intervention will be the main driver of compliance and improved standards.

5.3 The OPCAT provisions relating to the direct inspection role of the SPT run parallel to the expectations of the national or domestic National Preventive Mechanisms (NPMs). In this context, Article 18(4) is of particular importance:

When establishing national preventive mechanisms, States Parties shall give due consideration to the Principles relating to the Status and Functioning of National Institutions for the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights[18] (The Paris Principles).

These Principles reinforce the OPCAT criteria and, in the case of any ambiguities that may emerge, will serve to clarify the underlying intent.

5.4 Article 17 of OPCAT requires that States Parties shall ‘maintain, designate or establish ... one or several national preventive mechanisms’. This provision is important, indeed crucial, in the context of a federal State such as Australia, in that it reinforces Article 3 and clarifies that the NPM can be decentralised and can consist of multiple bodies, as long as all such bodies are ‘in conformity with the OPCAT provisions’.

5.5 Article 18(1) requires that ’States Parties should guarantee the functional independence of the NPM as well as the independence of their personnel’. It is implicit from the overall terms of OPCAT that functional independence demands something more than administratively sanctioned existence. The Paris Principles spell this out in Article 2 (Competence and Responsibilities):

A national institution shall be given as broad a mandate as possible, which shall be clearly set forth in a constitutional or legislative text, specifying its composition and its sphere of competence. [Authors’ emphasis]

5.6 Article 18(3) requires States Parties to ‘make available necessary resources for the functioning of the NPM’. The Paris Principles are more explicit as to funding and more strategic as to objectives:

The national institution shall have an infrastructure which is suited to the smooth conduct of its activities, in particular adequate funding. The purpose of this funding shall be to enable it to have its own staff and premises, in order to be independent of the Government and not be subject to financial control which might affect its independence[19] [Authors’ emphasis]

5.7 Articles 4(1) and 19(1) establish the key principle that the jurisdiction of the NPM must be visits-based. Specifically, Article 4 requires that ‘each State Party shall allow visits’ by the SPT itself and the NPM established pursuant to OPCAT to all categories and places of detention within the remit. Article 19(1) requires that the NPM should be allowed to ‘regularly examine the treatment of persons deprived of their liberty in places’ within the remit of OPCAT.

5.8 To be fully effective, a visits-based inspection system must be able to be conducted in the context of full information as to the operation of detention systems in the State Party. This involves the NPM having access to data as to the number of detainees and the detailed categories and places of detention, as well as all information relating to the treatment of those persons as well as their conditions of detention (Article 20(1) and (2). This necessarily would seem to involve access to documentary sources within the control of the detaining authority, an interpretation reinforced by Article (b) of the Paris Principles (Method of Operation). [20] It also reinforces our view that a prime obligation of the NPM must be to carry out a stock-take and make an inventory of all categories and places of detention within Australia.[21]

5.9 A visits-based inspection system also involves free and unfettered access to those places (Article 20(3)), the freedom to choose which places it wishes to visit at any given time (Article 20(5)) and the right to have private interviews with both detainees and ‘persons whom the NPM believes may supply relevant information’ (Article 20(4)).

5.10 It is well understood that, in closed institutions, detainees or anyone else who cooperates with external accountability agencies are sometimes victimised for doing so. The OPCAT criteria attempt to address this problem in Article 21:

(1) No authority or official shall order, apply, permit or tolerate any sanction against any person or organization for having communicated to the NPM any information, whether true or false, and no such person shall be otherwise prejudiced in any way.

(2) Confidential information collected by the NPM shall be privileged. No personal data shall be published without the express consent of the person concerned.

In other words the State Party must do all within its power to ensure that the effectiveness of OPCAT processes is not sabotaged or undermined by victimisation or the fear of victimization.

5.11 An element in establishing the confidence of detained persons or others in the NPM is its composition and status. Article 18(2) refers to the need for experts ‘to have required capabilities and professional knowledge’. The same Article refers to the need for ‘gender balance and adequate representation of ethnic and minority groups’. This reinforces Article 18(1) which, as mentioned above, requires the independence of NPM personnel to be guaranteed.

5.12 The Paris Principles add a specific dimension to this, providing that where Government Departments are represented on a national institution such as a NPM ‘their representatives should participate in deliberations only in an advisory capacity’.[22] Full membership is inappropriate, and would be contradictory to functional independence. Yet the links with Government should be such as to enable the policies of prevention and collaboration with States Parties to be achievable.

5.13 The same Article of the Paris Principles emphasises the desirability of links with NGOs (civil society) and also with national Parliaments.

5.14 The standards against which the NPM (and also the SPT when it inspects directly) should evaluate categories and locations of detention refer back to the terms of UNCAT. These are cast as ’torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment’. At this early stage, before the first inspection reports of the SPT[23] have been published, it can only be surmised how these standards will be interpreted. However, it is not unreasonable to suppose that, initially, OPCAT standards will draw upon the evolving and now well delineated standards of the European CPT.

5.15 On that basis, it can be expected that the standards will go well beyond identifying individual repression or wrongdoing (though it will include any such matters) to the broad question of whether the category or place of detention is being managed in a way that is decent and equitable. The so-called ‘decency agenda’ of the Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales has, from a different statutory source, come to cover much the same ground as the CPT standards and may well provide a starting point for Australia’s NPM. OPCAT provides that the NPM shall have the ‘right to have contacts with the SPT, to send it information and to meet with it’, so it can be anticipated that the philosophical leadership as to applicable standards will emanate from that source.

5.16 However, the broad thrust is towards the ‘harmonisation’ of national legislation with UN instruments.[24] It is likely that this will leave some room for the development of domestic standards that are equivalent in intention but different in detailed application. It is also important to recognise that NPM standards should be seen as representing a floor rather than a ceiling.[25]

5.17 At the conclusion of a visits-based inspection, OPCAT provides that the NPM should be able to ‘make recommendations to the relevant authorities’. The obligation of the State is to ‘examine the recommendations of the NPM and enter into a dialogue with it on possible implementation measures’. These provisions serve to emphasise that the OPCAT model seeks to proceed by way of collaboration and negotiation rather than exposure and humiliation.

5.18 The publication provisions reinforce this, requiring only that States Parties undertake to disseminate and publish the annual reports of the NPM. Similarly, with regard to reports of direct SPT inspections, it is provided that:

The SPT shall publish its report, together with any comments of the State Party concerned, whenever requested to do so by that State Party. If the State Party makes part of the Report public, the SPT may publish the Report in whole or in part. (Article 16(2))

Article 16(3) mirrors the NPM provision by stating that the SPT shall present a public annual report.[26]

5.19 The policy of putting collaboration ahead of publicity or exposure is a clear and deliberate one.[27] In practice, the sister organisation CPT has evolved to a point where only one State still puts barriers in the way of full publication, and it may be expected that the SPT will evolve in a similar manner. In the Australian context of relative transparency of the deliberations of numerous accountability agencies, it would seem sensible for NPMs to publish individual, not merely annual, reports after appropriate discussions with Departments and with the usual safeguards as to privacy.

5.20 The policy of collaboration and prevention is further reflected by the provision in Article 19(3) that the NPM should be able to ‘submit proposals and observations concerning existing or draft legislation’. This seems designed to encourage the NPM to be thematic or strategic in its approach to relevant human rights issues, not merely reactive.

6 Developing an OPCAT-compliant NPM in Australia

6.1 In considering the ways in which the NPM should be structured in Australia, it is necessary to be clear as to what it is expected to do, what processes it must apply, and the criteria it must adopt. The foregoing discussion has identified the key factors. In summary, they can be listed as follows:

- The NPM can be de-centralised and can consist of multiple bodies.

- If it is de-centralised, those multiple bodies must all conform to OPCAT provisions.

- The NPM must have functional independence and its personnel must be independent.

- The mandate of the NPM should be set forth in a constitutional or legislative text.

- The NPM must have adequate funding, have its own staff and be independent of Government.

- The remit of the NPM must be carried out in a visits-based manner.

- The NPM must have access to data relating to the number and locations of detainees and all information about their treatment as well as the conditions of their detention.

- In this context, there must be access to all relevant documentation.

- The NPM must have free and unfettered access to all categories and places of detention.

- The NPM must be able to set its own agenda for visits.

- Inspection visits should be regular.

- The NPM must be able to have private interviews with detainees and other persons whom it believes may be able to supply relevant information.

- The State Party must do all within its power to ensure that the effectiveness of OPCAT processes is not undermined by victimisation of informants or the fear of victimisation.

- As a corollary, communications with informants must be protected by confidentiality provisions.

- Membership of the NPM must draw upon experts and achieve a gender balance and adequate representation of ethnic and minority groups.

- Standards to be applied by the NPM will evolve from interpretation of UNCAT and OPCAT, with leadership emanating from the SPT. It can be anticipated that the standards developed within the European CPT framework will be influential. However, there will be room for domestic Australian standards that are equivalent in intention but different in detailed application.

- OPCAT standards will represent a floor, not a ceiling, so that domestic Australian standards can in principle exceed those required by OPCAT.

- The NPM is entitled to make recommendations in its reports, and the relevant authorities should enter into a dialogue with the NPM as to possible implementation measures.

- The Annual Report of the NPM must be published.

- Although there is no OPCAT requirement that individual inspection reports must be published, that should be the medium term objective.

- Publication must be handled in such a way as to be reconcilable with the policies of collaboration and prevention which above all underlie OPCAT.

- The NPM is entitled to be thematic or strategic in its approach to its works and its Reports and should be accorded access to Government to comment upon existing or future legislation.

6.2 To be OPCAT-compliant, the NPM arrangements adopted in Australia need to include provisions that take account of the 22 factors listed in paragraph 6.1. As mentioned in paragraph 4.2, the overall arrangements must also cover the parallel provisions relating to the role of the SPT both as an inspection body and as the contact point and overall policy leader for the NPM.

Constitutional Issues[28]

6.3 Australian constitutional law is renowned for its intricacies and subtleties and there will undoubtedly be claims in some quarters that any proposed Commonwealth law to give effect to OPCAT would be unconstitutional. However, it is difficult to see any significant constitutional impediment to such legislation provided it is properly structured and tied directly to OPCAT.

6.4 Section 51(xxix) of the Constitution provides as follows:

The Parliament shall ... have power to make laws for the peace, order and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to:-

...

(xxix) external affairs.

This provision has been interpreted so as to empower the Commonwealth Parliament to enact national legislation to achieve full implementation, within the States and Territories as well as within the Commonwealth itself, of international obligations under bona fide international treaties or conventions to which Australia is a State Party.[29] The Commonwealth Parliament can choose the form that the implementing law takes, but must ensure that (a) it does not depart too widely from terms of the treaty or convention and that (b) it is ‘reasonably capable of being considered appropriate and adapted to implementing the treaty’.[30]

6.5 There are also a number of other principles, some of which are rather under-developed, and none of which would seem to hinder legislation to implement OPCAT. First, the High Court has indicated that if the Commonwealth seeks to rely on a treaty to support a law made under the external affairs power:

It is not sufficient that the law prescribes one of a variety of means that might be thought appropriate and adapted to the achievement of an ideal. The law must prescribe a regime that the treaty has itself defined with sufficient specificity to direct the general course to be taken by the signatory states.[31]

There may be occasions when this ‘sufficient specificity’ test is difficult to apply. However, this paper has already shown[32] that the intention and terms of OPCAT lend themselves to sufficient specificity.

6.6 Secondly, there appear to be limits on the extent to which the Commonwealth can impose legislative requirements if these requirements interfere with the ability of the States to function as a government.[33] This area of law is evolving but it does not seem to hinder appropriate legislation in this area. Indeed, under our preferred model (see below), the NPM will build on, complement and enhance existing good governance processes.

6.7 There are several ways in which the Commonwealth could choose to exercise its legislative power. They include the following:

- The Commonwealth could enact a statute creating a unified NPM in relation to all categories and places of detention in Australia.

- The Commonwealth could enact legislation requiring each State and Territory to establish for that jurisdiction a single body to cover all categories and places of detention within that jurisdiction, whilst establishing also a national coordinating NPM. This would have responsibility for categories and places of detention within the Commonwealth’s direct legislative power as well as being the peak national body.

- The Commonwealth could identify areas that it considered particularly needed direct national coordinating NPM oversight and create a unified NPM for that category or categories of detention, whilst requiring each State and Territory to establish a single body to cover all other categories and places of detention within that jurisdiction.

Each of these approaches would be constitutionally valid and in conformity with Article 17. There could also be variants of any of these main approaches. For example, the Commonwealth could permit a State or Territory to divide the NPM coverage within its own jurisdiction between several agencies. In practical terms such an arrangement would tend to fragment OPCAT compliance, unless it was also provided that in such cases the State or Territory would designate one such body as the relevant NPM, with the other agencies operating according to a devolved model.[34]

Model 1: A Unified Commonwealth NPM

6.8 This model would require a very large agency, for the coverage would have to include every location contemplated by OPCAT across eight State/Territory jurisdictions plus the Commonwealth itself. To give something of the feel of its potential size, the Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services in Western Australia has a staff of 18 to cover inspection activities in relation to about 50 per cent of the State-based activities within the OPCAT remit. Again, the staff of the UK Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, covering just one aspect of OPCAT matters,[35] is just over 50.

6.9 Thus, a single unified agency to cover all categories and places of detention across the whole of Australia to OPCAT standards of frequency and intensity could require a workforce of no fewer than several hundred. The benefits of proceeding in such a way could include: the development of an integrated culture within the workforce; the readier achievement of consistency of standards across the whole of Australia; and the development of expertise for related functions, such as an accreditation system for prisons and other categories and places of detention,[36] and a research capacity in relation to related matters.

6.10 The drawbacks would seem to be more cogent, however. These include: considerable recurrent costs; duplication of corporate services that already exist within cognate agencies; probable recruitment problems when so many specialists are being sought to staff a new agency; possible drawbacks that can follow from excluding a political entity (the relevant State or Territory) from participating in regulating its own activities; and a sense that the federal body may be too remote from local realities. Despite the fact that some federal States have chosen or will choose a unified national NPM agency,[37] the traditions and practicalities of Australian Commonwealth/State relations are such that a unified model is unlikely to be necessary, appropriate or acceptable.[38]

6.11 The question was posed earlier: Can the energy of existing governance and administrative mechanisms be harnessed and re-directed so as to meet OPCAT standards for NPM arrangements? We suggested that it is good organisational theory and practice also to reside the accountability for activities in the ‘public authority’ (sovereign government) that is responsible for those activities. On balance, therefore, it would seem preferable not to adopt the model of a unified Commonwealth NPM.

Model 2: Mixed Model Based on Commonwealth & State Responsibilities

6.12 The second alternative is to put the responsibility for OPCAT compliance on the respective jurisdictions. Administratively and conceptually, this would work best if there is ‘horizontal integration’ within each jurisdiction, i.e. if a single body is created (or designated) within each jurisdiction to act as the NPM for all categories and places of detention. That approach in turn would facilitate ‘vertical integration’ between the jurisdiction-based NPMs and the national coordinating NPM, which must certainly be a Commonwealth agency.

6.13 A number of examples will serve to bring out the attractions and the complexities of this model. The first relates to Western Australia. This State already possesses an OPCAT-compliant inspections body – the Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services. Its culture, methodology and standing already are such that it could naturally evolve into a full-blown NPM. This could be done by relatively straightforward legislative change extending the categories and places of detention that would henceforth be within its remit, and consequentially increasing its human and financial resources. The add-on costs would be relatively modest because of the economy of scale that would be achieved. The main additional areas to be covered would be: closed psychiatric wards (already covered by a quasi-compliant body, the Council of Official Visitors, so that some kind of transitional arrangement could readily be managed) and police lock-ups and stations.[39] With regard to these, the existing remit in relation to court custody centres ensures that the Office has a peripatetic presence in the regions as well as a strong presence in the metropolitan area. Secure child welfare centres would also readily fit existing jurisdiction, which covers juvenile detention centres relating to the criminal jurisdiction.

6.14 In summary, the Western Australian situation could readily be adapted so as to achieve full horizontal integration within that particular jurisdiction. From the point of view of vertical integration into the national coordinating NPM, an established inspectorate with a culture that is already familiar with the standards contemplated by OPCAT (and indeed already ahead of those standards in some important respects) would fit naturally and positively.

6.15 However, the situation is rather different in other jurisdictions. Queensland provides a good example.[40] In that State, there is no OPCAT-compliant accountability agency functioning in relation to any of the applicable categories or places of detention. However, there are bodies that exercise a more circumscribed (and usually less independent) inspections role. Three illustrations will make this clear.

- Prisons. The Queensland Prisons Inspectorate lacks functional independence as it is accountable to the CEO of the operational department. Furthermore, the governing legislation appears to treat the Inspectorate primarily as a body that investigates specific incidents and complaints rather than as a body with a standing remit and power to examine and report on systemic issues.

- Juvenile Detention Centres. As we understand it, an inspection team located in the Department of Communities inspects juvenile detention centres every three months, but the team lacks functional independence as it reports to the CEO and its reports are confidential. The Commissioner for Children and Young People also plays a role and can appoint ‘community visitors’ to inspect such institutions, but the powers of such visitors are somewhat constrained. For example, they may only enter a place of detention by warrant or with the consent of the person in charge of the detention centre. In practice, the Commissioner’s office seems essentially to respond to complaints not to inspect on a regular or sustained basis for systemic issues.

- Closed Psychiatric Wards. The responsibilities of the Queensland Director of Mental Health include ‘ensuring the protection of the rights of involuntary patients’ and appointing ‘approved officers’ to ensure the ‘proper and efficient administration’ of the Mental Health Act 2000. However, these approved officers do not have unfettered access, the Act stating that they may visit facilities between 8.00 am and 6.00 pm. Furthermore, the approved officers are accountable to the Director of Mental Health.

6.16 Within Queensland, therefore, there are bodies which currently perform monitoring roles with respect to prisons, juvenile detention centres and closed psychiatric wards. Their expertise will become highly relevant to the development of any future OPCAT inspections regime. However, it is equally clear that a new OPCAT-compliant model will need to be established. We will come later to the question of whether existing non-compliant models could be reformed and then designated as the NPM. The most obvious candidates would be the respective state-based Ombudsman or Human Rights bodies. Provided proper legislation and processes are in place, it probably would not matter whether the State in question opted for a new body or for bolstering an existing body. But it is desirable that the multiple NPM model should remain as relatively simple as possible: preferably there should be a single body in each jurisdiction, ensuring and epitomising horizontal integration.

6.17 In terms of the Commonwealth, it will be recalled that its main areas are: places of military detention; immigration detention centres; prisoners held for breaches of Commonwealth criminal law; police cells/lock-ups administered by the AFP; and aged care homes or hostels. In addition, there may be places of detention operated by national security services.

6.18 With regard to military detention, the Defence Force Discipline Act 1982 (Cth) does not contain any reference to monitoring and accountability. However, Part II of the Defence Force Discipline Regulations1985 (Cth) contains a number of provisions regarding matters such as accommodation requirements, meals, cleanliness, exercise, work, religious freedom and visits. There is also reference to 'visiting officers'. These officers are appointed by an 'authorised officer' and their duties include visiting detention facilities ‘at such times or at such intervals as an authorised officer directs’. After each visit, the visiting officers are to furnish a report to the ‘proper authority’. It has not been possible for us to ascertain how well these inspection arrangements function in practice. However, the regulations fall well short of OPCAT requirements with respect to matters such as functional independence.

6.19 Immigration detention facilities are subject to a number of rather uncoordinated mechanisms. The Migration Act 1958 (Cth) does not establish any specific inspection mechanisms for such facilities. However, the Australian Human Rights Commission (the Commission), as part of its broad accountability function in relation to human rights, now conducts visits-based inspections. The 2007 report, Summary of Observations following the Inspection of Mainland Immigration Detention Centres, is OPCAT-compliant in all key respects. The 2004 report, National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention: A Last Resort, was a model of comprehensive systemic review of a particular aspect of immigration detention; this report was based on a three-year investigation, and its revelations anchored the focus of the Commission upon this aspect of Australian immigration detention practice. Previously, in 2001, the Immigration Detention Advisory Group had been established, but it originally lacked functional independence. De facto, its status and processes appear to have improved since then so that, for example, the membership is known and some of its reports have been placed on the Department of Immigration and Citizenship’s website. However, it falls well short of OPCAT standards in several ways, not least in being simply a creature of administrative fiat. The Commonwealth Ombudsman, starting from reviews of individual cases, has also undertaken significant work in this field.[41] Patchwork mechanisms of this sort, even viewed as a whole, are confusing in terms of responsibility and accountability. The situation with regard to immigration detention, therefore, exemplifies the need for an integrated NPM structure.

6.20 For obvious reasons, it is not possible to obtain clear information about any places of detention that may be operated by Australia’s national security services. However, facilities of this sort would be subject to the jurisdiction of the Inspector General of Intelligence and Security (IGIS).[42] We understand that the Inspector General also liaises closely on relevant matters with the Commonwealth Ombudsman. It is unclear from the information available to us whether the processes are OPCAT-compliant.

6.21 With regard to aged care homes, there appears to be an active and well-resourced inspectorate (the Aged Care Standards and Accreditation Agency) operating across Australia. Interestingly, the Minister very recently announced that the inspection operations of the Agency will be significantly expanded in 2008-2009.[43] It is intended that there will be 7,000 inspections over this period, 3,000 of which will be unannounced. The notion of unannounced visits is very much in line with OPCAT thinking, as are some of the other aspects of the legislation.[44] For example, authorised officers have significant powers to inspect and enter premises; where necessary, they can seize items; and there is an obligation on people on the premises to cooperate with monitoring officer. However, it is not clear whether the inspection standards reflect the scope of OPCAT criteria or indeed what exactly constitutes an ‘inspection’. Thus, there are a number of ways in which the Act might require amendment in terms of OPCAT. For example, consideration would need to be given to whether a ‘monitoring warrant’ should still be required from a magistrate before the authorised officer can enter a home without consent. Nevertheless, this scheme appears readily capable of being fine-tuned to the point where it is OPCAT-compliant.

6.22 The AFP is subject to various kinds of accountability by external bodies, notably the Commonwealth Ombudsman. There can be no question as to that office holder’s functional independence or powers. However, it needs to be clarified whether, in looking at and reporting upon the ‘practices’ of the AFP under Divisions 3 and 4 of the applicable legislation,[45] the Ombudsman’s remit or practices extend to the treatment of persons held in custody from time to time by the AFP and whether their treatment was cruel, inhuman or degrading.[46] The documentation that is available suggests that this has not been a guiding principle in the Ombudsman’s work to date.[47]

6.23 With regard to Commonwealth prisoners, they are held in State prisons. Section 120 of the Constitution states as follows:

Every State shall make provisions for the detention in its prisons of persons accused or convicted of offences against the laws of the Commonwealth, and for the punishment of persons convicted of such offences, and the Parliament of the Commonwealth may make laws to give effects to this provision.

At any given time in recent years there have been about 700 such persons in this category.[48] The most practical arrangement would obviously be for the State and Territory NPM arrangements to primarily cover such persons. There is no doubt, however, that the Commonwealth could bring them within its own NPM structure if it chose to do so.

6.24 It can thus be seen that there is a patchwork of accountability mechanisms already in existence in relation to various categories and places of detention falling within Commonwealth jurisdiction, but that predominantly they are not OPCAT compliant. This is not really surprising, for such accountability mechanisms as do exist were not established in a context of safeguarding individual human rights and complying with newly-evolving international standards. Ideally, the Commonwealth should, like the other jurisdictions, horizontally integrate its NPM activities. The manner in which this might be done will be discussed later.

Model 3: Mixed Model with Some Activities Reserved to the Commonwealth.

6.25 Our previous discussion and Working Paper show that in some areas of State responsibility there are a few bodies already in existence that either meet OPCAT criteria or would be capable of being upgraded to become OPCAT compliant. However, there is one notable exception in our primary category of places of detention, namely, police stations and lockups. Although internal standards have been more widely developed and the police are subject to some level of external review by general accountability agencies, these agencies tend to focus on corruption, misconduct and associated issues. As such, they are largely irrelevant to OPCAT.[49]

6.26 The fact that there are no State-based models on which to build suggests that this is an area in which the Commonwealth might give consideration to making the status of police inspection activities truly national. There are at least four other reasons why this would be desirable:

- It would match the increasing integration of, or at least coordination between, police forces in Australia that has occurred in recent years and is ongoing.

- It would encourage national consistency in the development of national standards for police detention practices as they bear upon human rights.

- It would allow the national coordinating NPM a defined and direct role in a critically important OPCAT area.

- There would be a sharing of expertise and resources in a new area, with associated cost benefits.

6.27 It can be predicted that there will be strong resistance in some quarters to such a national model for police lockups and stations. However, interesting parallels can be drawn here with the United Kingdom. Police forces in the UK are still relatively independent of each other; for example, the ‘Thames Valley Police’ and the ‘Greater Manchester Police’ have separate Chief Constables and lines of accountability / management. Historically there have also been significant cultural differences between police forces in different parts of the country. For example, the Metropolitan Police has always had a somewhat different culture from the regional Constabularies and there have been differences between Northern Ireland and the mainland. It seems quite clear that the cultural and practical differences between the different UK police services are at least as great as those across Australia. However, there is just one national police inspectorate for the UK, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary.

6.28 Under this third approach, then, the State and Territory NPMs would cover all categories and places of detention other than: (a) those that fall directly within Commonwealth law; (b) those (probably only police lock-ups and stations) that fall within a deliberate Commonwealth policy to reserve NPM jurisdiction to itself.

The national coordinating NPM

6.29 We strongly recommend Model 2 or Model 3 rather than Model 1. Models 2 and 3 are easily reconcilable in terms of legislative implementation, once the policy decision has been made as to whether the Commonwealth should take responsibility for an activity – police lock-ups and stations - that would otherwise fall within State or Territory NPM remit.

6.30 Under either of these models, there would be multiple NPMs – probably eight in the States and Territories plus the national coordinating NPM. Obviously, the SPT could not deal effectively with multiple NPMs, even if their remit in relation to their own jurisdiction were comprehensive and integrated. There would need to be a single national coordinating NPM. The coordinating role of this body would be as follows:

- To oversee and direct an immediate stock-take of all places of detention and to update this register over time.

- To exercise quality control over the activities of the other NPMs (for convenience they will now be described as the ‘subsidiary’ NPMs).

- To carry out sample inspections at various locations covered by the subsidiary NPMs.

- To carry out inspections of places of detention falling within its direct jurisdiction.

- As a contact point to deal with the SPT on all matters related to OPCAT compliance by Australia. This would include information flow and advice as to the locations or category of detention to be inspected by SPT as part of its own direct jurisdiction.[50]

6.31 As we have said, the national coordinating NPM would necessarily be a Commonwealth-constituted body and would not only be the national contact point but would also have responsibility for inspecting some categories and places of detention. This leads inevitably to another question: should the national coordinating NPM be an existing Commonwealth agency or is it preferable to create a new agency specifically dedicated to the task?

6.32 Where an agency already exists that possesses the skills, experience and culture to carry out tasks of this kind, it is usually preferable to empower it to carry out related tasks rather than set up an additional agency. This is so for a variety of reasons:

- There is an economy of scale in doing so, for personnel can be deployed across the whole range of the agency’s activities, as required.

- The corporate services for an enlarged agency do not usually need to be expanded in direct proportion to the increase in the size of the operational workforce.

- Ministerial and other governmental relations, including regional and international relations, have already been established and tested.

- An existing agency can get up to speed in relation to the related activities more quickly than an entirely new one.

6.33 To this point in the development of OPCAT, 15 out of 35 States Parties that have ratified OPCAT have nominated NPMs.[51] Before the end of 2008 Germany will become the 36th State to ratify. In every case so far, the 15 States have chosen to designate existing agencies rather than to establish a new body. Seven States Parties have nominated their Ombudsman, seven have nominated their Human Rights Commission, and one has designated its generalist Inspection Commission as the national NPM. Local governance structures, priorities, administrative convenience and available resources clearly influence the choice of the NPM in each case.

6.34 Only one of those 15 States Parties, Mexico, is a federal State. It comprises 31 States and a Federal District. Mexico has chosen the national (federal) Human Rights Commission (CNDH) as the NPM. Within the CNDH a distinct NPM unit has been formed. To achieve coverage of so many places of detention (estimated at over 5,000) in so many States extending over such a great geographical area,[52] the CNDH wants to collaborate with the Human Rights Commissions of the 31 States. Unlike Australia, the federal government of Mexico does not have the constitutional power to impose a collaborative statutory structure. Thus, to do so will involve entering into formal agreements. To date only five such agreements have been signed. The view of the CNDH is that such agreements do not confer the status of an NPM upon the State Human Rights Commission but merely authorise it to act in collaboration with, or as a delegate of, the CNDH. So Mexico has opted for a ‘mixed model’ that is different from any of the models mentioned previously in that it is neither a comprehensive and unified national NPM nor does it formally confer the status of NPMs upon subsidiary agencies.[53]

6.35 The Mexico NPM has visited 348 detention places in the 12-month period September 2007 to September 2008. Eight reports have been published and four more are in the pipeline. The SPT has also inspected Mexico in the course of a three-week visit in July 2008.

6.36 Another federal State that has ratified OPCAT is Argentina. Argentina comprises 24 jurisdictions: 23 provinces and the autonomous city of Buenos Aires. As of September 2008, debate is still occurring as to how its NPM arrangements may best be structured. With the still-recent history of horrific torture in Argentina, passions run strongly about the best way of creating a truly effective NPM. ‘Civil society’ (the NGO sector, academics and human rights activists) has views that go much further than those of the bureaucracy. At the time of this Report, it is not possible to predict what form the NPM will ultimately take.

6.37 The Federal Argentina Government has clear constitutional authority to ratify treaties, which then become incorporated into the national Constitution. The Federal Government is responsible internationally for their implementation. Legally, the various Provinces are expected to implement the requirements of the national Constitution. However, in practice this requires political and detailed legislative/administrative commitment at the Provincial level. Unlike the Australian Commonwealth government, the national Government does not have the power to compel action by Provincial legislatures. The overriding Commonwealth legislative power under section 51(xxix) of the Constitution will fortunately enable Australia to finesse this problem.[54]

6.38 As mentioned, Germany is about to ratify OPCAT. Germany comprises 16 Lander (State Governments) plus the Federal Government. A national scan of accountability agencies ascertained that there was not a single such body in Germany that was OPCAT-compliant. The decision has been made that there will be two NPMs – one (the Federal Centre for the Prevention of Torture) to deal with categories and places of detention under federal law, and the second (the Commission for the Prevention of Torture) to deal with the numerically and functionally far more important categories and places of detention dealt with by Lander laws. This arrangement will require identical matching legislation to be passed by all 17 jurisdictions.

6.39 Switzerland will not ratify OPCAT until the second half of 2009. However, it has now been agreed by the 26 Cantons and the Federal Government that a single unified NPM will be established.

6.40 Reference to these four federal States – Mexico, Argentina, Germany and Switzerland – demonstrates that the models and approaches to the creation of a NPM vary according to local factors, but that there is some real attraction for establishing a centralised coordinating mechanism, or even a centralised model. In either event, the national State needs to commit additional resources and make required statutory amendments to enable the NPM structure to be OPCAT-compliant.

6.41 Although New Zealand is not a federal State, its model is interesting and possibly relevant to the Australian situation. The coordinating NPM is the Human Rights Commission. Four other national agencies are designated as subsidiary NPMs in relation to their particular spheres of governance responsibility. These are: the Office of the Ombudsman in relation to categories and places of detention within the purview of the Department of Corrections, as well as psychiatric detention; the Office of the Children’s Commissioner in relation to all aspects of the detention of children; the Independent Police Conduct Authority in relation to all categories and places of detention involving police; and the Inspector of Service Penal Establishments in relation to military detention.