An age of uncertainty - Inquiry into the treatment of individuals suspected of people smuggling offences who say that they are children

Foreword

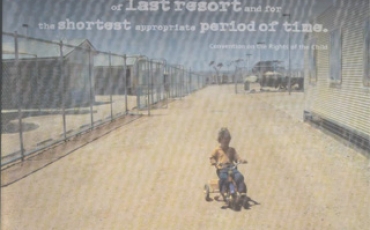

This report makes disturbing reading. It documents numerous breaches by Australia of both the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. As a nation that is understandably anxious that the rights of our own children should be respected when they come into contact with the authorities of other countries, it is troubling that between late 2008 and late 2011 Australian authorities apparently gave little weight to the rights of this cohort of young Indonesians.

The events outlined in this report reveal that, in the above period, each of the Australian Federal Police, the Office of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions and the Attorney-General’s Department engaged in acts and practices that led to contraventions of fundamental rights; not just rights recognised under international human rights law but in some cases rights also recognised at common law, such as the right to a fair trial. It seems likely that some of those acts and practices are best understood in the context of heavy workloads, difficulties of investigation and limited resources. Others, however, seem best explained by insufficient resilience in the face of political and public pressure to ‘take people smuggling seriously’; a pressure which seems to have contributed to a high level of scepticism about statements made by young crew on the boats carrying asylum seekers to Australia that they were under the age of 18 years.

Support for this conclusion is perhaps most obviously found in the authorities’ failure for a significant period of time seriously to question practices and procedures that led to young Indonesians who said that they were children being held in detention in Australia for long periods of time.

- The average period of time spent in detention by a young Indonesian crew member whose wrist was x-rayed but who was not charged with any offence was 5.4 months – with the longest period that an individual in this class was held being 9.8 months.

- The average period of time spent in detention by a young Indonesian crew member whose wrist was x-rayed but whose prosecution for people smuggling was eventually discontinued, in most cases because it was doubted that the Commonwealth could prove that he was over the age of 18 years when apprehended, was 14.4 months (of which an average of 6.6 months was spent in an adult correctional facility). The longest period that an individual in this class was held was just over two years, of which over 21 months were spent in an adult correctional facility.

These are periods of detention that Australian authorities would ordinarily consider quite unacceptable for children – or for young people who might be children – who had not been convicted of any offence.

Fifteen young Indonesian crew members were ultimately released on licence because there was doubt about whether they were adults at the time of their apprehension. The average period of their detention was 31.6 months, of which 28.8 months were spent in adult correctional facilities. The longest period that an individual in this class was held was 34 months, of which 32.6 months were spent in an adult correctional facility. Each of these young Indonesians had been sentenced to a mandatory term of imprisonment applicable only to an adult.

It is plain that Australian authorities were until recently reluctant to question whether wrist x-ray analysis provides a sound basis for a determination that a young person is over the age of 18 years – notwithstanding the growing, and eventually compelling, evidence that it does not. It is difficult to judge whether this is further evidence of a high level of scepticism about claims to be under the age of 18 years or evidence simply of a strong desire for a scientific means of establishing chronological age – or perhaps both.

This reluctance to question the usefulness of wrist x-rays for the purpose for which they were being used is most clearly seen in the continued reliance by the AFP and the CDPP on a particular radiologist who used this technique – notwithstanding that each of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists; the Australian and New Zealand Society for Paediatric Radiology; the Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group; and the Division of Paediatrics, Royal Australasian College of Physicians had expressed the view that the technique was unreliable and untrustworthy.

An unwillingness to question this inherently flawed technique can equally clearly be seen in the failure of the Office of the CDPP to identify that it was under a duty to examine whether it could continue to maintain confidence in the integrity of the evidence being given by the radiologist engaged by the AFP, and under an obligation to disclose to the defence the material in its possession that tended to undermine his evidence.

The same unwillingness is apparent in the failure by AGD to review the contemporary literature which critically examined the technique; to seek independent expert advice to assist its understanding of that literature; and thereafter to provide informed and frank policy advice to the Attorney General – including advice concerning the risk that reliance on the technique had led, and would continue to lead, to children wrongly being identified as adults.

The dogged reliance on wrist x-ray analysis as evidence of maturity appears for a significant period of time to have contributed to inadequate efforts being made to obtain documentary evidence of age from Indonesia and to the giving of limited, if any, weight to such evidence when assessments were made of the ages of the young Indonesians. Furthermore, that reliance appears to provide at least part of the explanation for the results of focused age assessment interviews conducted in late 2010 being disregarded.

The result of reliance on wrist x-ray analysis, together with inadequate reliance on other age assessment processes, was the prolonged detention, including in adult correctional facilities, of young Indonesians who it is now accepted were, or were likely to have been, children at the time of their apprehension.

I recognise that in late 2011 Commonwealth agencies stopped relying on wrist x-ray analysis where there was no other probative evidence of age; made increased efforts to obtain documentary evidence of age from Indonesia and modified their opposition to weight being given to evidence from Indonesia. At the same time, the Department of Immigration and Citizenship commenced to conduct focused age interviews with young Indonesian crew members who said that they were children and now only refers for criminal investigation those who are assessed by this process to be adults. These factors have led to a significantly improved approach to the assessment of whether young Indonesians suspected of people smuggling are older than 18 years of age – one which is less likely to lead to errors and therefore less likely to result in breaches of the rights of children.

Moreover, on 2 May 2012, the Attorney-General announced that a review would be conducted by AGD of the cases of 22 individuals identified by the Commission and the Indonesian Embassy as having been convicted of people smuggling offences in circumstances where substantial reliance had been placed on wrist x-ray evidence, or where age was raised as an issue but ultimately not pursued. The review involved further collaboration between the Commonwealth agencies, as well as the AFP’s engaging with the Indonesian National Police to seek verified age documents from Indonesia, and DIAC conducting age assessment interviews in order to assess retrospectively the ages of crew at their time of arrival in Australia. During the course of the review, its ambit was extended to include the re-examination of the cases of a further six individuals. The outcome of the review was announced on 29 June 2012. Of the 28 crew whose cases were re-examined as part of the review, 15 individuals were released early on license on the basis that there was a reasonable doubt that they were over 18 years of age at the time they were apprehended; a further two individuals were released early on parole; three crew completed their non-parole periods prior to the commencement of the review; and eight crew were assessed as likely to have been adults at the time they were apprehended.

The recommendations of this report are intended to assist in creating a lasting environment in which the rights of young Indonesians suspected of people smuggling are respected and protected in every interaction they have with Australian authorities.

It is my hope that this Inquiry will additionally lead to mature reflection on the strengths and weaknesses of our criminal justice system more generally. The Inquiry has revealed that this system may be insufficiently robust to ensure that the human rights of everyone suspected of a criminal offence are respected and protected.

To this end, I urge all of the agencies involved to give consideration to how the human rights of this cohort of young Indonesians came to be breached in the ways outlined in this report. Careful consideration should also be given to the steps that need to be taken to ensure that in the future Australia does respect the human rights of all who comes into contact with our system of criminal justice.

Catherine Branson QC