Launch of Children's Rights Report 2016

Introduction

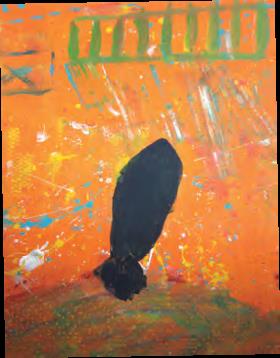

Good morning everyone. I want to begin by speaking about an artwork submitted by a young person detained in a youth justice centre. This was sent to me as an entry to an art competition I ran for children and young people in youth justice centres this year.

I asked them to show me how they felt, what they wished for and what they needed. Many of the entries can be seen around the room.

This work is titled ‘In captivity’. The dark shape floating in the middle represents a killer whale. The young person used ‘the ideas of colour to reflect feelings in the black shape (the whale) to represent himself. He had been learning about Tilikum, the Orca that was kept in capacity at Sea World and eventually after years of trauma killed his trainer’.

To me the whale appears lost, helpless and without hope or direction. He is trying to swim up to the surface but his path is blocked. The water around him evokes a whirlpool of emotions. And the message is clear - for children, experiences of trauma and abuse have a lasting legacy.

OPCAT and youth detention

This year, the main focus of my Children’s Rights Report was a national review of the treatment and oversight of children and young people in correctional detention in Australia. The information collected during this investigation was assessed against the criteria for United Nations Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment (known as OPCAT).

As has been discussed, the purpose of the OPCAT is to assist countries in implementing the Convention Against Torture, to which Australia has been a party since 1989. In particular, the OPCAT seeks to prevent mistreatment through comprehensive and transparent oversight systems.

The distressing footage that emerged from Don Dale Youth Detention Centre in the Northern Territory earlier this year, and subsequent reports from Cleveland Youth Detention Centre in Queensland, starkly illustrates the need for improved oversight and monitoring mechanisms of these closed environments.

Secure environments such as these create particular power imbalances and vulnerabilities which require careful monitoring and a high level of transparency to prevent abuses from occurring. By adding children into the mix that risk is only heightened.

The OPCAT sets out a monitoring system made up of two complementary bodies at the international and national level – the UN Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture and a National Preventive Mechanism.

By ratifying the treaty Australia would be allowing the UN Subcommittee to conduct visits to any place of detention within Australia and advise the government of ways to improve protections in those environments.

The National Preventive Mechanism (or NPM) would draw on the routine oversight work within Australia and issue regular reports. In Australia, it is likely that there would be one overarching body at a national level that coordinates the different delegated bodies in each jurisdiction.

In my work this year, I specifically looked at how each jurisdiction measured up in relation to the OPCAT criteria for a National Preventive Mechanisms. The purpose was to identify the main challenges moving forward and highlight ways that different jurisdictions can learn from initiatives and practices in other states and territories. Ultimately, while most jurisdictions have bodies which meet some of the NPM criteria, no jurisdiction meets all of the criteria.

For example, some jurisdictions have independent inspectorates but questions have been raised about the extent of their independence from government departments running the youth justice systems. Several jurisdictions rely on independent Ombudsmen which have generally have strong powers in relation to investigations. However, they do not all have mandates to regularly visit youth justice centres and tend to play a more complaints-based role. Most states and territories have Children’s Commissioners or Guardians but many are not specifically mandated to undertake inspections or access or publish information.

All jurisdictions have reporting requirements, to varying extents, for things like the use of force, restraint and isolation. However, these are often not comprehensive and are often prescribed as policy rather than in legislation. And they mostly do not come with any requirement of transparency – that is, there is rarely any public reporting of those records. Even the jurisdictions with some of the more comprehensive and public reporting appear to be falling short in practice. For example, somehow, even with compulsory reporting of segregation to the Ombudsman NSW, there appears to have been young people in NSW kept in solitary confinement for extended periods of time. In summary, the legislative and regulatory regimes in all jurisdictions need reviewing and tightening up.

What did children and young people in detention tell me

As part of this year’s work I consulted with children and young people in detention about their rights and ways to make sure their rights were being met while they were locked up. I spoke with nearly 100 children and young people in youth justice and adult correctional facilities across Australia. I would like to tell you about some of things that children and young people told me.

Most children and young people I spoke to knew that they had temporarily lost their right to freedom. But, they were largely unaware that they had any other rights – in fact, 31% said they were not told about their rights when they arrived, and a further 33% could not recall if they we told about their rights. When I discussed their rights with them, contact with loved ones, education, access to health and professional services were among the rights they most valued.

In particular, I heard about the importance of being respected and the difference that respectful and fair treatment by staff made to their day to day life and in turn to their behaviour towards others. As one young person explained ‘we aren’t all bad people just cos we’re locked up.’

During our conversations, the children and young people raised the damaging effects of collective punishment, body searches, and the use of physical force. They told me that long periods of segregation or isolation as a form of punishment left them ‘sad’, ‘angry’ and ‘depressed’. One child said he felt ‘like an animal’.

The factors which young people felt impacted their wellbeing in youth detention align with the basic human rights found in the major international treaties like the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Children and young people in youth justice centres may have lost the right to liberty as a result of criminal behaviour. However, in losing their freedom, these young people have not forfeited their other basic human rights so important to their development as human beings.

One of the most important of these is being able to have a voice, to make complaints and seek redress. Many children and young people knew how to complain but most were unwilling to make a compliant or raise an issue because of either fear of retaliation by staff or a belief that nothing would get done.

Recommendations

The main recommendations of this year’s report relate to the urgent ratification and implementation of the OPCAT; and the development and publication of data that tells us more about the treatment of children and young people and their outcomes.

In this regard, I made a number of recommendations relating to how states and territories and the commonwealth can move forward in relation to youth justice oversight. I am urging the governments in all states and territories to make use of my report and of the OPCAT framework to undertake reviews of their own systems.

I also recommended a changes to enhance accountability through monitoring and national reporting of things like use of force and isolation and outcomes measures for incarcerated children.

Implementing these recommendations would help to ensure a more systematic, human rights-based schema of safeguards for protecting. the rights of children and young people while they are incarcerated. I also made a number of other recommendations relating to the rights of juveniles who offend or who are involved in the criminal justice system.

For example, I have recommended that the age of criminal responsibility be raised in all jurisdictions from 10 years to 12 years, in line with the recommendations of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child explicitly states that children under 18 should not be held in detention with adults. The evidence suggests that co-locating children with adult offenders is likely to worsen the behaviour of those children and young people and will only expose them to safety risks and criminal associations.

Currently, all jurisdictions in Australia have the legislative power to put children under 18 years of age in adult prisons under certain circumstances. Most jurisdictions told us that they rarely use this power.

Until very recently, Queensland stood in stark contrast to the other states and territories by treating young people aged 17 years as adults within the criminal justice system.

Recent amendments ended automatic transfer of 17 year olds to adult prisons. After a transition time of around a year, we expect that there will no longer be 17 year olds held routinely in adult prisons.

I welcome these changes in Queensland and the recognition that it is very much not in the best interests of those children and their future outcomes to be held in adult prisons.

In this regard I recommend that Australia withdraws its reservation to article 37 (c) of the CRC on the obligation to separate children from adults in prison.

Conclusion

It is clear to me that we need to view our treatment of children and young people in detention in an entirely different way.

We need highly skilled and trained workers who are able to form and model constructive respectful relationships with children and young people. Children also need specialist programs and activities that emphasise education and rehabilitation and which recognise and respond to the traumatic backgrounds from which they have come. Failure to do this misses a unique opportunity to influence developing brains and evolving human beings in positive ways.

By neglecting children’s rights in youth justice contexts we are most likely to entrench criminal associations and identities, and provide a feeder service to the ranks of the adult criminal justice system. Not only does this make no sense in terms of building a safe cohesive society, it is a bad investment that costs more than $438 million annually.

Finally, in order to ensure that we are never again confronted with what happened at Don Dale and Cleveland we also need to improve how we monitor such places.

Strong oversight would ensure that these facilities are run in line with community standards, lift the quality of treatment of detainees, and help prevent the abuses occurring in the first place.

Because, while there should always be consequences for wrongdoing, there is never any justification for the abuse and mistreatment of children.