Conference: Realising the Rights to Health and Development for all

Archived

You are in an archived section of the website. This information may not be current.

This page was first created in December, 2012

The Close the Gap Campaign

Tom Calma

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social

Justice Commissioner

Australian Human Rights Commission

International Conference on Realising the Rights

to Health and Development for all

Hanoi, Vietnam

Tuesday 27

October 2009

SLIDE 1

I’d like to begin by acknowledging the conference organisers: the

Central Commission for Popularization and Education of The Communist Party of

Vietnam, and The University of New South Wales Initiative for Health and Human

Rights, and particularly Professor Daniel

Tarantola.

And I acknowledge my fellow speakers, and you in the

audience.

To introduce myself, I am an Australian Aboriginal elder from the Kungarakan

tribal group and a member of the Iwaidja tribal group whose traditional lands

are south west of Darwin and on the Coburg Peninsula in the north of Australia,

respectively.

SLIDE 2

I have been involved in Indigenous affairs at a local, community, state,

national and international level and worked in the public sector in Australia

for over 35 years.

From 1995 to late 1998 I worked as a senior Australian diplomat in India and

from 1998 to 2002 in Vietnam representing Australia’s interests in

education and training.

And can I say what a great joy it is to return to your beautiful country for

which I have such fond memories and many good friends. My family are very

envious because I am here so we have agreed to return to Hanoi in December for a

family holiday.

In Australia I now work as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social

Justice Commissioner. This involves monitoring the human rights of Indigenous

Australians and I report annually – in the Social Justice Reports -- to

the Australian Parliament in that regard.

And as Commissioner I am a member of the Australian Human Rights Commission

which was established in 1986. We are an independent statutory organisation and

the premiere human rights institution operating in Australia. We are also the

Australian Government’s implementing agency under the Vietnam - Australia

Human Rights Technical Cooperation Program which has been operating since 1993

and has resulted in many meaningful and valued dialogues between our two nations

on human rights issues.

The Close the Gap Campaign

SLIDE 3

I am here today to talk about human rights and the practical application of

the right of health through the lens of the Close the Gap Campaign for

Indigenous Health Equality. I will be talking about the Campaign in some detail

today, but it is, in short, a campaign that aims to ‘close the gap’

between the health status and life expectation of Indigenous and non- Indigenous

Australians.

The Campaign is a non government initiative and while it is directed to one

sector of society, the principles are applicable to all societies, the world

over.

SLIDE 4

One of my responsibilities as Commissioner is to act as the Chair of the

Steering Committee behind the Campaign. The campaign is supported by all of the

key Indigenous and non-Indigenous health bodies in Australia.

And, as is appropriate in a human rights based campaign dealing with social

development, leadership of the Campaign is from Aboriginal peoples and their

representative bodies.

Through our members we draw on broader Aboriginal community support. For

example, the peak Aboriginal health body known as NACCHO represents over 140

Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services across Australia, each governed

by elected community representatives.

And the main human rights based elements of the Campaign are on the slide and

they are:

- Partnerships between Indigenous peoples and all Australian governments

(central and provincial). - A national plan for health equality by 2030 – a generation

- Ambitious targets and benchmarks and monitoring and evaluation

mechanisms

Some background - what is the problem?

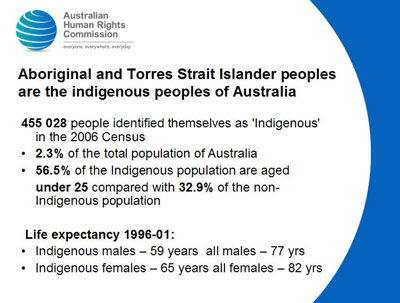

SLIDE 5

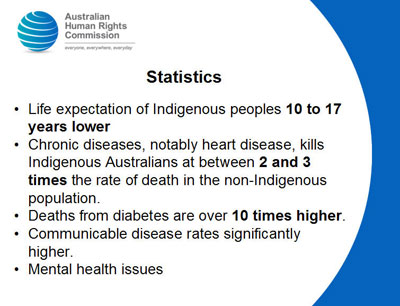

Let me highlight some statistics on why the campaign is necessary:

- While non - Indigenous Australians enjoy one of the highest life

expectancies in the world, Indigenous Australians are dying (according to

various official estimates) at between 10 and 17 years younger.

- Chronic diseases, notably heart disease, kills Indigenous Australians at

between 2 and 3 times the rate of death in the non-Indigenous population. Deaths

from diabetes are over 10 times higher.

- And this remains the case across many indicators for communicable diseases

as well as mental health indicators also.

SLIDE 6

We are very clear about the fact that Indigenous health inequality is the

result of a failure to realise the right to health of Indigenous

Australians:

- to ensure Indigenous Australians had the same opportunities to be as healthy

as other Australians

- to take effective action to remedy long-standing and substantial health

inequalities (with, for example, special measures), and

- to address a range of rights subject matters that impact on Indigenous

health – that is, the social and cultural determinants of health.

Over the last 50-years the health of Australians has improved

significantly due to major advances in medical care and rising prosperity.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, however, have not shared in

the same benefits and in fact our life profile is similar to people living in

rural Bangladesh.

SLIDE 7

The main causes of health inequality are clear. And they are reflected in the

two main right to health subject matters – health services and health

infrastructure.

- In relation to the first, Indigenous Australians suffer a lack of access to

primary health care. Primary health care aims to prevent disease from occurring

in the first place, or to detect it early. As a result, illnesses that could be

prevented become chronic problems.

- And in relation to the second, overcrowded and poor quality housing in many

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, and limited access to fresh

and healthy food, are also major contributors to health inequality. In 2006,

Indigenous adults were five times more likely to live in overcrowded homes than

other adults.

Indigenous Australians are also – on the whole – poorer

than other Australians as a result of years of being marginalised from the

mainstream economy. In 2006, approximately 40% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islanders adults were in the bottom 20% of incomes which is actually an increase

from 1996 (36%). And as I am sure we are all aware here, poverty and poor health

are closely linked.

And for that reason the Campaign does not merely focus on health services or

diseases, We also looks at the social determinants of health such as housing,

education and employment and so on.

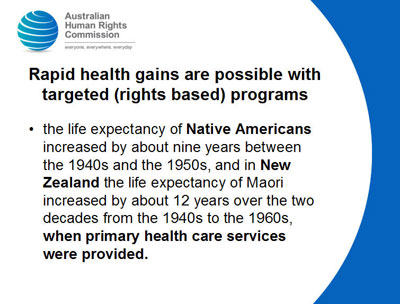

The Campaign is built on evidence that shows that significant improvements in

the health status can be achieved within short time frames.

SLIDE 8

For example, the life expectancy of Native Americans increased by about nine

years between the 1940s and the 1950s, and in New Zealand the life expectancy of

Maori increased by about 12 years over the two decades from the 1940s to the

1960s, when primary health care services were provided.

And in Australia, death rates among Aboriginal people from pneumonia have

dropped by 40 per cent since 1996, following the roll-out of pneumococcal

vaccinations. And a program known as the 'Strong Babies, Strong Culture'

maternal health program has shown that significant reductions in the number of

low birth weight babies can occur within a matter of years.

The key elements of the Close the Gap Campaign are aligned with the basic

tenets of the right to health and the progressive realization principle that is

set out in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Thus we are asking for:

SLIDE 9

- A comprehensive national plan of action that is properly resourced and that

has the goal of achieving Indigenous health equality by 2030. - A partnership with Indigenous peoples and their representatives.

- A targeted approach to achieving Indigenous health equality, focusing on a

wide range of health conditions and health determinants. - Support for Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services.

And the good news is that Australian governments, both central and

provincial, have already committed to this approach. In December 2007 they

publicly committed to closing the life expectancy gap within a generation, and

halving the mortality gap between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and

non-Indigenous children under 5-years of age.

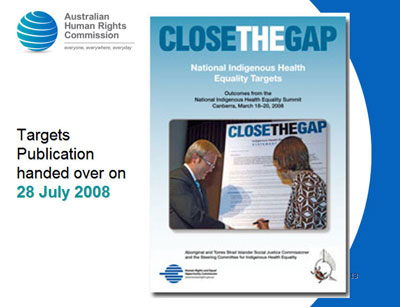

This was followed by the Close the Gap Statement of Intent, signed by the

Prime Minister in March 2008. The Close the Gap Campaign partners also organised

the first-ever National Indigenous Health Equality Summit in Canberra in March

2008.

There, the Prime Minister, the Minister for Health and Ageing and the

Opposition Leader among others agreed to work in partnership with Aboriginal

people in relation to the following key commitments:

SLIDE 10

- To developing a comprehensive, long-term plan of action, that is targeted to

need, evidence-based and capable of addressing the existing inequities in health

services, in order to achieve equality of health status and life expectancy

between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non- Indigenous

Australians by 2030, and

- To ensuring primary health care services and health infrastructure for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are capable of bridging the gap in

health standards by 2018.

We say a national plan for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

health equality should include:

- a coordinating body to oversee and guide the work of the many Australian,

State and Territory government agencies responsible for delivering health

services for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population; and

- a monitoring body, as accountability is essential in the human rights

approach

SLIDE 11

The plan too should address all the factors that contribute to Indigenous

health inequality. And as I am sure all here are aware, such a national plan

– in this case for health equality – is a fundamental human rights

obligation of governments, and particularly when faced with extreme inequality

along racial lines. In that regard, the Campaign can be viewed as asking for, in

human rights terms, a special measure to address inequality.

Now the bad news is that there is no such national plan as yet, but the past

18 months have seen the Australian Government involved in a series of reforms

including - potentially - to the entire health system. Our challenge now is to

bring the government’s attention back to the development of a national

plan.

A partnership approach to achieve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

health equality is another key element of our approach, and the human rights

approach to development.

SLIDE 12

This means that we work with peak health bodies and peoples’

representative bodies as appropriate, such as the Aboriginal Community

Controlled Health Services. Additional partners would include the Indigenous and

non Indigenous health professional bodies and a national Indigenous

representative body when it is established.

Support for Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services as the preferred

model for the delivery of primary health care is another element of the

Campaign, reflecting the human right of Indigenous peoples to design and deliver

there own services along with governments, more broadly stemming from their

right to self determination. These services provide a vast range of care

supporting complex health needs, and in away that is culturally appropriate to

the communities they operate in. They are also – and this is crucial in a

human rights context - accountable to the communities they serve.

SLIDE 13

The National Indigenous Health Equality Targets are another major feature of

the Campaign. These were developed by leading experts in Indigenous health and

focused on:

- the leading causes of Indigenous child mortality - including low birth

weight, respiratory and other infections and injuries - the leading contributing factors to the life expectancy gap – chronic

disease, injuries and respiratory infections - mental health and social and emotional well being - which are crucial to

achieving better health.

An additional set of targets is being developed by the Close the

Gap Campaign partners to address the broad range of social and cultural factors

that have a profound influence on the health of Indigenous Australians.

SLIDE 14

Despite some set-backs, the Campaign has been enormously successful as a

driver -- putting Indigenous health equality 'on the map' and shaping policy.

Overall $4.6bn in new money has been devoted to addressing Indigenous

disadvantage in part at least as a result of the Campaign’s activities.

And $1.6bn has been devoted to Indigenous health.

The challenge ahead for us remains to keep Australian governments to their

commitments to a comprehensive national planning process and to also embrace a

true partnership with Indigenous Australians.

That is the human rights based approach. And it’s not just a matter of

rights for right’s sake. Human rights are practical and grounded in common

sense from a policy perspective. Call them what you like, but without

partnership and a national plan with ambitious but realistic targets it stands

to reason, I believe, that the best made plans of central governments will not

be fully effective.

It’s absolutely vital that the people whom governments are hoping to

help in any given policy context are active players in the design and delivery

of the policies and programs that result. That is the lesson of the Close the

Gap Campaign and that is the lesson that I hope to leave with you today.

Thank you.

SLIDE 15